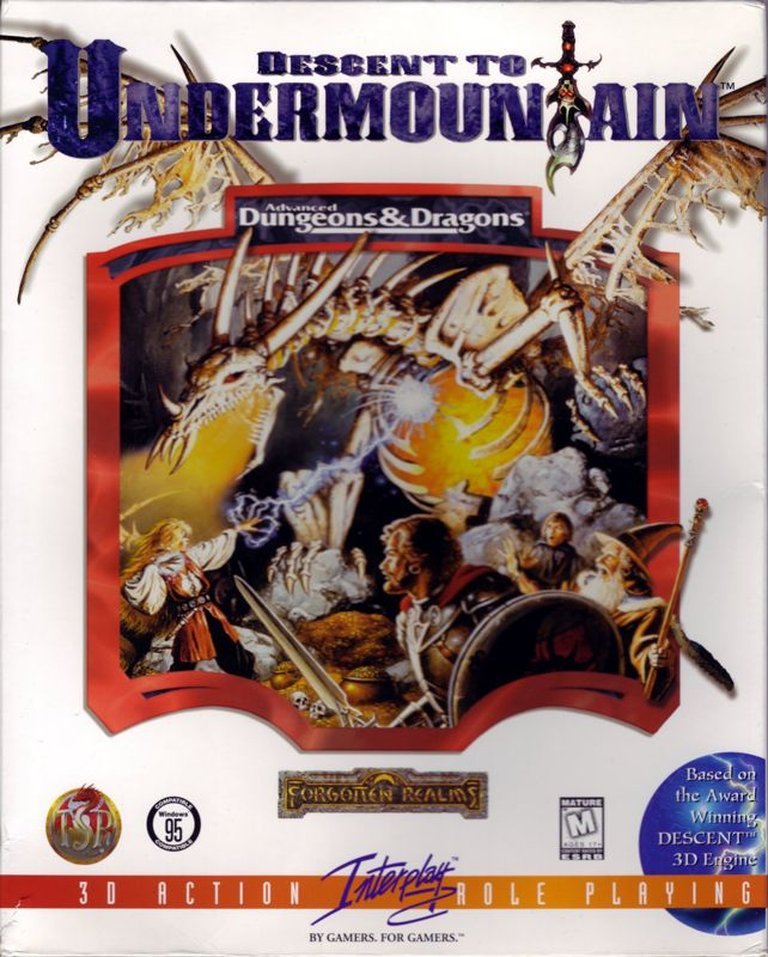

- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: DOS, Windows

- Publisher: Interplay Productions, Inc.

- Developer: Interplay Productions, Inc.

- Genre: Action, Dungeon crawler, RPG

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Character development, Combat, Exploration, Puzzles

- Setting: Dungeon, Fantasy, Forgotten Realms

- Average Score: 41/100

Description

Descent to Undermountain is a first-person RPG set in the Forgotten Realms of Dungeons & Dragons, where players investigate mysterious disappearances in the city of Waterdeep by exploring the perilous underground labyrinth of Undermountain. Using the Descent engine, the objective is to locate eight pieces of an amulet to gain control of the legendary Flame Sword of Lolth, thereby saving Waterdeep from an army威胁.

Gameplay Videos

Descent to Undermountain Free Download

Descent to Undermountain Patches & Updates

Descent to Undermountain Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (41/100): The game that inspired laziness in the game industry.

mobygames.com (41/100): The game that inspired laziness in the game industry.

Descent to Undermountain Cheats & Codes

PC

Enter codes by typing them during gameplay or at the character stats screen.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| hometaser | Sets all stats to 18 |

| shrinkiwankill | Grants the ultimate sword |

| mesmart | Provides all spells and spell scrolls |

Descent to Undermountain: A Monumental Misstep in the Forgotten Realms

Introduction: The Allure and the Abyss

In the mid-1990s, the personal computer role-playing game (CRPG) was undergoing a profound technological metamorphosis. The monolithic, turn-based, grid-oriented experiences of the “Gold Box” era were giving way to immersive, real-time, first-person perspectives. Two titans dominated the conversation: the atmospheric, sprite-based dungeon crawls of Eye of the Beholder and the revolutionary, polygon-powered space combat of Descent. The notion of merging these two pillars— injecting the rich narrative, character depth, and tactical combat of a Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) licensed RPG into the true-3D, six-degree-of-freedom engine of Descent—was a proposition of staggering, almost irresistible ambition. It promised the holy grail: a fully realized, free-moving 3D fantasy world where you could truly look up, down, and around every corner of a vast dungeon. Descent to Undermountain, released by Interplay in January 1998, was the catastrophic result of that ambition. This review argues that the game stands not as a flawed classic, but as a canonical case study in development hubris, technical mismatch, and corporate pressure, where a potentially groundbreaking concept was systematically dismantled by a perfect storm of poor engineering choices, a profoundly unsuitable engine, and a rushed, broken release. Its legacy is one of infamy, serving as a stark warning about the perils of forcing a square peg into a round hole, with the peg being a beloved RPG license and the hole being a physics engine designed for zero-gravity spaceship dogfights.

Development History & Context: A Perfect Storm of Mismatched Vision and Crushing Deadlines

The Studio and the Vision: Interplay Productions in the late 1990s was a studio of immense prestige and clout. Having shepherded the Descent series, the groundbreaking Fallout, and the cult classic Redneck Rampage, they were masters of diverse genres. The project originated from a 1995 announcement, capitalizing on the synergy between their proprietary, award-winning Descent 3D engine and the immensely popular Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D) 2nd Edition license held by TSR. The initial pitch was audacious: a cooperative, four-player multiplayer dungeon crawl set in the iconic Forgotten Realms city of Waterdeep and its infamous super-dungeon, Undermountain. Key designers included future Obsidian legend Chris Avellone, alongside Scott Bennie, John Deiley, Robert Holloway, and Steve Perrin.

The Fatal Engine Choice: The Descent engine was a marvel of its time for one specific context: six-degree-of-freedom movement in an industrial sci-fi environment. As creative director Michael McConnohie noted early on, the engine’s core architecture was fundamentally hostile to an RPG. Its collision spheres—the invisible boundaries defining objects—were designed for large, sleek spacecraft, not the intimate, up-close melee combat of sword-and-sorcery. Retooling this system for bipedal creatures wielding hand weapons required a near-total rewrite of the engine’s most basic physics, a task of monumental complexity that was chronically underestimated.

The Production Collapse: Development was immediately fraught. According to multiple sources, including post-mortem analyses from industry veterans like Eric Bethke, the project ballooned in budget and timeline. The engine’s unsuitability caused constant redesigns. The game reportedly passed through no fewer than three internal development teams over nearly two years. The final team inherited a morass of unfinished, unstable code. With a hard Christmas 1997 deadline looming—a deadline the game would ultimately miss, shipping on January 15, 1998—Interplay made a fateful decision. As programmers later admitted on Usenet, the game was released in a state far from finished to meet corporate-mandated dates. The promised four-player co-op was quietly axed. The “lively” 3D acceleration support that Descent II had pioneered was entirely absent. This was not a case of a small indie studio overreaching; this was a major publisher, with a sterling reputation, consciously shipping a flagship, triple-A title in a state of disrepair. The betrayal of consumer and reviewer trust was profound.

Technological Context: The game’s release window was critically unlucky. It arrived just as Quake (1996) and Hexen II (1997) had redefined expectations for 3D-accelerated, hardware-accelerated graphics in fantasy settings. Meanwhile, The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall (1996) and Ultima Underworld II (1993) had already demonstrated that vast, immersive first-person fantasy worlds were possible with more purpose-built engines. Descent to Undermountain felt archaic even before it shipped, using a modified version of a two-year-old engine with no support for the 3D cards rapidly becoming standard.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Solid Lore, Squandered Potential

On paper, the plot is a serviceable, even classic, Forgotten Realms adventure. The player, an adventurer of chosen race and class, arrives in Waterdeep seeking work from the city’s high mage, Khelben Blackstaff. A mysterious wave of disappearances leads back to the depths of Undermountain, the colossal, labyrinthine dungeon built by the mad wizard Halaster Blackcloak. The quest unfolds as a series of missions from Khelben, revealing a MacGuffin hunt: the eight fragments of the Spider Amulet, the only thing capable of controlling the Flame Sword of Lolth. This artifact, sought by the Drow (dark elves) of the Demonweb Pits, can raise an infinite undead army from the Abyss. The final confrontation is with the Spider Queen herself, Lolth.

Thematically, the game touches on classic D&D motifs: the corrupting allure of power, the ever-present threat of the Drow and their demonic patron, and the exploration of a malevolent, seemingly endless dungeon. The setting is authentically Forgotten Realms, with the Yawning Portal inn serving as a classic hub. However, the narrative execution is uniformly flat. Dialogue is functional, delivered through static screens with purple-blue text overlays that freeze the game. There is no voice acting, and the written interactions are simplistic, offering little in the way of role-playing nuance or character development for the player’s party. The “eight amulet pieces” plot device results in a highly linear, fetch-quest structure, with each dungeon “level” accessed only after completing the previous one for Khelben. The rich tapestry of Undermountain—a place with a deep, storied history in D&D lore—is reduced to a series of disconnected, thematically generic monster lairs (goblin caves, drow holds, demonic pits). The potential for emergent storytelling, meaningful faction play, or a sense of a living dungeon is entirely absent. The lore is present but inert, a skeletal framework never given flesh by the game’s systems or presentation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Broken Promises and Glimmering Cinders

Character Creation & AD&D 2nd Edition: The game’s one unqualified success is its character creation system. Players choose from six races (Human, Elf, Dwarf, Halfling, Gnome, Half-Orc) and four core classes (Fighter, Thief, Cleric, Mage), with multiclassing allowed for certain races, adhering closely to AD&D 2nd Edition rules. Statistics (Strength, Intelligence, etc.) are rolled, and these directly impact combat rolls, spell success, skill checks (like lockpicking), and saving throws. The system is robust and faithful, allowing for classic archetypes from Drizzt-esque Drow Rangers to sturdy Dwarven Fighters. The 2D character portraits are also widely praised as exceptionally well-drawn and atmospheric.

Core Gameplay Loop & Combat: The loop is straightforward: receive a quest at the Yawning Portal, descend into a designated section of Undermountain, fight monsters, solve simple puzzles (mostly lever/switch/key hunts), retrieve an item or defeat a boss, return for reward and the next quest. Combat is real-time, but based on AD&D’s “speed” factor and “attacks per round,” creating a system where faster characters can act more frequently. In theory, this blends action and tactics. In practice, it is a catastrophic failure due to the engine.

The combat is plagued by:

* Abysmal AI: Enemies exhibit “lurching,” slippery movement, often failing to pathfind properly, smashing into walls, or phasing through geometry. They frequently fail to notice the player attacking them, making encounters feel trivial and deterministic rather than dynamic.

* Collision Catastrophe: The engine’s ship-based collision model is wholly inappropriate for humanoid combat. hit detection is notoriously inconsistent. Swinging a sword often requires precise, unnatural positioning, leading to frantic, frustrating circling of enemies. The infamous “floating monsters” bug—where non-flying creatures hover or bob in the air—directly results from the leftover zero-gravity physics from Descent.

* Lack of Tactical Depth: The environment and AI provide no meaningful tactical opportunities. There is no flanking, no use of terrain, no complex spell targeting (spells are generally area-of-effect or single-target casts). The promised puzzle integration is rudimentary.

Progression & Loot: Character progression follows AD&D: experience points from kills and quests lead to level-ups, with improvements to hit points, spells, and abilities. Loot consists of gold, generic weapons/armor, and occasional magical items (up to 160 are claimed). This loot can be sold at the hub for better gear. The system works but is barebones, lacking the complex item crafting, unique artifacts, or meaningful装备 choices of contemporaries like Fallout or Baldur’s Gate.

User Interface (UI): The UI is widely criticized as clunky and intrusive. The default view often includes large status bars and information panels that consume significant screen real estate. Dialogues halt gameplay with an ugly color overlay. Managing inventory and spells is functional but not intuitive. The overall presentation feels dated and unpolished.

The Ghost of Multiplayer: The complete removal of the advertised four-player co-op mode is perhaps the most glaring broken promise. The Descent engine natively supported networked multiplayer chaos. The fact that this core feature was cut late in development due to “severe technical issues” (per Home of the Underdogs) underscores the fundamental mismatch between the engine’s design and the RPG’s architectural needs. The dream of cooperative dungeon crawling in a true 3D world died with this feature cut.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Technical and Aesthetic Disaster

Visuals: The Engine’s Failed Metamorphosis: This is the game’s most notorious aspect. The Descent engine, in its original form, created dark, atmospheric, polygon-rich industrial corridors and detailed enemy models for its sci-fi setting. Descent to Undermountain‘s artists failed to adapt it. Textures are notoriously pixelated, low-resolution, and muddy, with a pervasive, dull brownish-gray palette that makes every level feel visually identical. Character and monster models are crude, “low-polygon” by even 1997 standards, and are covered in stretched, unsightly textures that make most creatures look like “mutations.” The lighting is flat and unimpressive. Most damningly, the game offers no support for 3D acceleration, forcing players to rely on slow, CPU-bound software rendering. As reviewers noted, even on a Pentium-200 with 64MB RAM, the framerate was “nausea-indicating” at minimum settings. The promise of “true-3D” became a joke, delivering a slower, uglier experience than sprite-based 2.5D engines like Build (Duke Nukem 3D) or even Interplay’s own Redneck Rampage.

Sound & Music: The sound situation is a bizarre anachronism. The game uses a primitive sound subsystem that reportedly only functions with a pure, vintage Sound Blaster 1.0 card—hardware virtually extinct by 1997. On modern systems or even common hardware of the time (SB Pro, 16, AWE32), sound effects and music often fail to initialize. This is an inexcusable oversight, especially given Interplay’s access to the superior Human Machine Interfaces (HMI) sound system used in other contemporary titles. When operational, the sound effects are described as “decent, albeit unspectacular,” and the music is atmospheric but unmemorable. The technical failure here is so profound it suggests a complete lack of quality control.

Atmosphere & Design: The level design exacerbates the visual failings. Dungeons are sprawling, maze-like, and visually homogenous. The promised variety—from icy caves to fungal forests to Drow cities—is rendered with the same dreary, polygonal texturing, failing to create distinct environmental storytelling. The sense of exploring a legendary, terrifying mega-dungeon is lost in repetitive corridors and a lack of memorable set-pieces. The atmosphere is one of technical struggle and visual fatigue, not dark fantasy wonder.

Reception & Legacy: The Pariah of the D&D License

Critical Savaging: Descent to Undermountain was panned universally, with a MobyGames critic average of 41%. Scores ranged from a high of 76% (from Game.EXE, a notably forgiving publication) to lows of 10-20% from Reset, PC Games, and Computer Games Magazine. Common criticisms were universal: abysmal graphics and framerate, game-breaking bugs, terrible AI, and a feeling of profound unfinishedness. GameSpot‘s terse conclusion, “pushing a product out the door before it’s ready makes loyal customers angry,” became a common refrain. Next Generation gave it one star, praising only the character creation for its D&D fidelity. PC World (Australia) called it “woeful,” hoping the upcoming Baldur’s Gate would “redeem Interplay.”

Commercial & Cultural Aftermath: The game was a commercial disappointment, quickly forgotten and discounted. Its cultural impact is defined by its infamy. It has been repeatedly cited as the worst official Dungeons & Dragons video game ever made. Its legacy is twofold:

1. A Cautionary Tale: It became the prime example of “shipping too early,” cited in post-mortems and industry analyses (like Eric Bethke’s Game Development and Production). It demonstrated the catastrophic results of mismanagement, unrealistic deadlines, and forcing technology into a role it was never designed to fill.

2. An Industry Meme: Interplay itself acknowledged the disaster with a self-deprecating Easter egg in the acclaimed Fallout 2 (1998). A magic 8-ball item in the Shark Club bar has the response: “Yes, we KNOW Descent to Undermountain was crap.” This single line encapsulates the company’s awareness of its failure and has become the game’s enduring epitaph. It effectively “made everyone forget about Gorgon’s Alliance and the entire previous two years of atrocious D&D games” (GameSpy), not by being good, but by being so spectacularly bad it redefined the bottom.

Influence: Its influence is negative—a stark lesson. It arguably contributed to a brief industry skepticism toward true-3D engines for CRPGs, slowing adoption until purpose-built engines like Infinity (Planescape: Torment, Baldur’s Gate) and later Gamebryo/Elder Scrolls engines proved the concept could be done correctly. It stands in stark contrast to the masterpiece that followed: Baldur’s Gate (1998), which used Bioware’s Infinity Engine to create a rich, 2.5D (sprite-based) masterpiece that revived the CRPG genre. Descent to Undermountain showed what not to do.

Conclusion: The Definitive Verdict

Descent to Undermountain is not merely a bad game; it is a fascinating, tragic artifact of development gone catastrophically wrong. Its premise—a true-3D, first-person D&D RPG—was visionary. Its execution was a masterclass in failure. The Descent engine, a masterpiece for space combat, was the wrong tool for this job, and the decision to persist with it led to insurmountable technical debt. The rushed, deadline-driven release, which sacrificed core features like multiplayer and stability, transformed a problematic project into an embarrassing liability.

To judge it by its intended promise is to see a ghost of a groundbreaking title, a “what-if” that haunts gaming history. To judge it by the product on the shelf (or the ISO) is to confront a broken, ugly, nauseating experience with a single, redeeming feature: a technically solid AD&D character generator. It has no meaningful combat, no engaging world, no atmospheric immersion, and no technical polish. It is a game that literally makes players sick and crashes to DOS.

In the grand canon of video games, Descent to Undermountain holds a unique, ignominious position. It is the cautionary tale whispered in producer meetings, the textbook example of how corporate pressure and technological misjudgment can destroy even the most promising of concepts. Its only lasting legacy is the Fallout 2 easter egg—a wry, corporate mea culpa that ensures this chapter of Interplay’s history, and the wider industry’s, will never be forgotten. For historians, it is essential study. For players, it is a testament to the necessity of patience, polish, and respecting the tools you wield. Avoid it not because it is merely bad, but because engaging with it is an exercise in frustration, a descent into the undermountain of game development hubris.