- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: InertiaSoft Ltd.

- Developer: InertiaSoft Ltd.

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: 1st-person Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Board game

Description

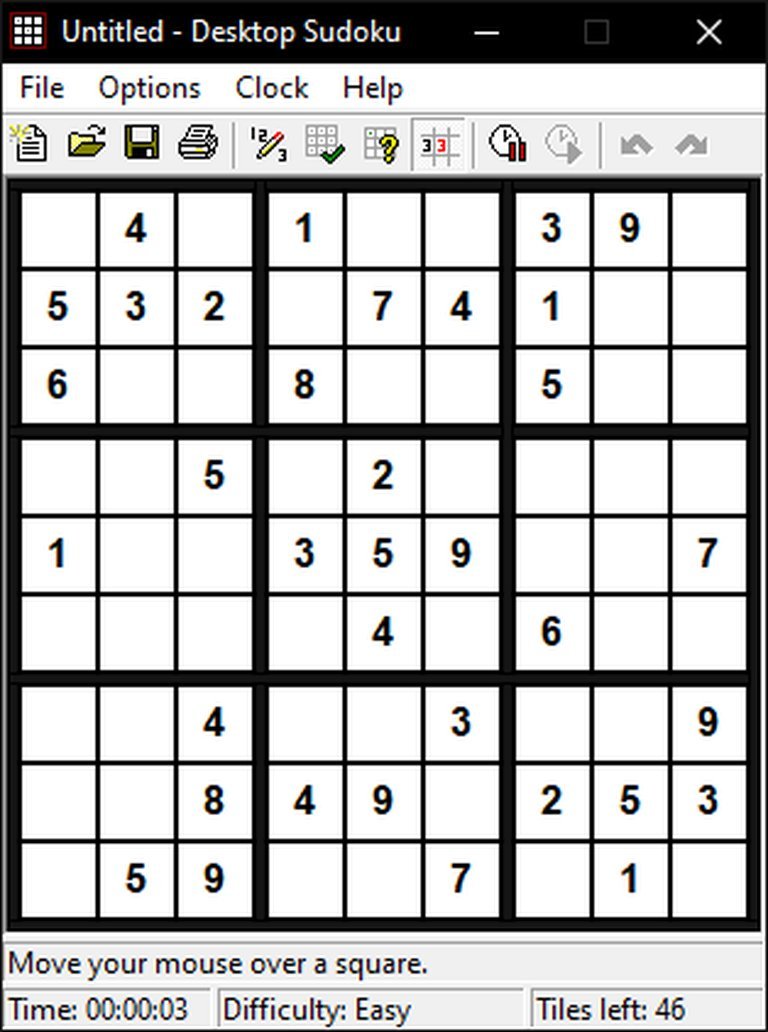

Desktop Sudoku is a digital adaptation of the classic number-placement puzzle for Windows, offering over 10,000 puzzles across four difficulty levels. Players can solve puzzles within the program or print them for paper-based play, with features like hint systems and autofill to assist in solving, providing a versatile and engaging experience for puzzle enthusiasts.

Desktop Sudoku: A Digital Artifact of the 2005 Puzzle Craze

Introduction

In the chronicles of digital gaming, certain titles exist not as revolutionary landmarks but as precise temporal markers—products of a specific cultural moment that capture an industry’s zeitgeist with almost documentary clarity. Desktop Sudoku, developed and published by the enigmatic InertiaSoft Ltd. and released for Windows in 2005, is precisely such a title. It arrived not to redefine its genre, but to dutifully service the unprecedented, global demand for digital logic puzzles ignited by the “Sudoku craze” of the mid-2000s. This review posits that Desktop Sudoku is a fascinating case study in utility-over-aesthetics, a bare-bones software utility that serves as a pure, unfiltered lens through which to view the peak of print-puzzle digitalization. Its historical significance lies not in innovation, but in its representative fidelity to a now-antiquated model of digital puzzle consumption: the desktop application as a direct, functional analogue to its paper counterpart.

Development History & Context: The “Desktop” Series and the 2005 Boom

The studio behind Desktop Sudoku, InertiaSoft Ltd., remains a shadowy entity with virtually no digital footprint beyond MobyGames listings. This obscurity is telling. Desktop Sudoku was not a passion project from a celebrated indie developer nor a flagship title from a major publisher. Instead, it was a calculated, low-risk product from a small studio seizing a blatant market opportunity.

The year 2005 was the absolute zenith of Sudoku mania. As detailed in the provided historical sources, the puzzle’s journey—from Howard Garns’s 1979 “Number Place” to Nikoli’s 1984 Japanese popularization, and finally Wayne Gould’s 2004-2005 global newspaper syndication—culminated in a worldwide obsession. The puzzle was dubbed “the Rubik’s Cube of the 21st century.” This created an immediate, massive demand for accessible, affordable digital versions. The gaming landscape of 2005, as outlined in the Wikipedia entry on the year, was dominated by console behemoths (Civilization IV, GTA: San Andreas) and the launch of the Xbox 360. Yet, in the quiet corners of the PC software market, a different gold rush was on.

Desktop Sudoku epitomizes this niche. It was a pure utility, part of a series that included Desktop Crossword, Desktop Solitaire, and Desktop Golf. The “Desktop” prefix was a branding convention of the era, signaling software designed to mimic or enhance a real-world desk activity. There was no pretense of “gameplay” in the traditional sense; this was a tool. Technologically, it represented the tail end of the classic Win32 desktop application era, before web-based and mobile app stores would subsume this market. Its constraints—a fixed/flip-screen visual style and point-and-select interface—were not artistic choices but the defaults of the simplest possible Windows Forms or similar GUI toolkit application. It existed in the vast, unsexy ocean of PC “productivity” and “entertainment” software sold in boxed copies at office supply stores or via shareware directories.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Elegance of Absence

To analyze the narrative of Desktop Sudoku is to engage in a profound exercise of subtraction. The game possesses no narrative, no characters, no dialogue, and no explicit themes. This absence is, however, its most defining and thematically resonant feature.

Desktop Sudoku embodies the philosophical purity of the puzzle itself. The provided sources repeatedly emphasize Sudoku’s core appeal: it is “logic-based,” requiring “no math,” a “brain exercise” based on “pattern recognition” and “deduction.” By presenting the puzzle in a sterile, narrative-free digital environment, InertiaSoft removed all extrinsic motivation. There is no “story” of a hero solving puzzles to save a kingdom, no avatar progression, no解锁成就 (unlocking achievements) in the modern sense. The only “plot” is the player’s internal journey from confusion to clarity for each 9×9 grid. The theme is pure, unadorned cognition. The act of filling the grid becomes a meditation on order emerging from chaos, a digital mandala. In this sense, Desktop Sudoku is a direct descendant of the “Latin Squares” of Euler and the “magic squares” of ancient tradition—a vessel for a timeless human impulse to impose logical structure. Its thematic depth is found in what it lacks: any distraction from the fundamental, symbiotic relationship between the human mind and the grid.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Study in Functional Minimalism

Desktop Sudoku’s gameplay loop is as straightforward as its premise: receive a partially filled 9×9 grid adhering to Sudoku rules (each row, column, and 3×3 subgrid must contain digits 1-9 exactly once), and use logic to fill the remaining cells. The game’s systems are designed for maximum accessibility and minimum friction, reflecting its target audience of casual solvers and newspaper puzzle enthusiasts.

- Core Loop & Innovation: The loop is the classic iterative process of candidate elimination. The “innovation” is purely functional. The game’s primary value propositions, as stated in the MobyGames description, are its library of “over 10,000 puzzles” and its “four difficulty levels.” This scale was its main selling point—a virtually infinite supply of puzzles generated or curated to prevent repetition. It was a battery of challenges, not a crafted experience.

- Interface & Utility Tools: The interface is the epitome of point-and-select simplicity. The “hint” and “autofill” features are critical. The hint system likely reveals a single, logically deducible cell, serving as a gentle nudge for the frustrated solver. “Autofill” (or “pencil marks” automation) is the killer feature for digital Sudoku, eliminating the tedious manual tracking of candidates on paper. These tools acknowledged that the digital medium’s value lay in reducing the overhead of puzzle-solving, not in adding new mechanics. The ability to “print them to solve on paper” was a crucial concession to purists and a practical feature for commuters, showing an understanding of the hybrid print/digital habits of its user base.

- Flaws and Omissions: By modern standards, the systems are stark. There is no timer, no mistake counter, no cloud syncing, no daily challenge, no competitive leaderboards, and no variant puzzles (like Killer, Diagonal, or Samurai Sudoku). The “four difficulty levels” are likely crude, based on the number of initial “givens,” not on the sophistication of logical techniques required. The generation algorithm, if not hand-curated, might produce puzzles solvable by brute-force trial-and-error rather than pure logic, a common flaw in early digital Sudoku. The game assumes a single, correct solving path and offers no alternative strategies or tutorials.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of the Software Utility

Desktop Sudoku presents a world of absolute minimalism. Its “art” is the default UI of a Windows 95/XP-era application: grey or beige window frames, stark black-on-white grids, primary blue or grey for selection highlights. The “visual” perspective is listed as “1st-person, Top-down” with a “Fixed / flip-screen” style—terms that feel comically grandiose for what is essentially a static grid in a resizable window. There is no “world” to build; the setting is the Windows desktop itself.

The sound design is either entirely absent or consists of the faint, system-default Windows click sounds. There is no soundtrack, no ambiance, no auditory feedback beyond the most basic UI interactions. This sonic vacuum is intentional and consistent with the game’s ethos: it is a tool for concentration. Any music or sound would be an unwelcome intrusion into the silent, internal dialogue of deduction. The atmosphere is one of quiet, focused isolation, akin to working on a spreadsheet or writing a document. This austerity directly contributes to the experience by reinforcing the puzzle as an optical and intellectual object, stripping away all sensory distractions.

Reception & Legacy: A Silent Witness to a Phenomenon

Critical reception for Desktop Sudoku is virtually nonexistent in the historical record. It holds no MobyScore and has no critic reviews on MobyGames. This is not an anomaly but a reflection of its nature. It was not a “game” in the critic’s domain; it was a software utility, reviewed in the “puzzle” or “application” sections of PC magazines, if at all. It would have been evaluated on criteria like puzzle generation quality, UI responsiveness, and value for money—metrics absent from traditional game criticism.

Its commercial reception can only be inferred. It was one of thousands of similar Sudoku applications flooding the market in 2005-2006. Titles like Simple Sudoku (a highly regarded freeware alternative) and commercial packages from publishers like Astraware set the standard. Desktop Sudoku likely sold modestly through渠道 (channels) like software bundles, discount bins, and listings on early download portals. Its legacy is as a perfect specimen of the “shovelware” tier of the Sudoku boom—competent, unremarkable, and ultimately disposable.

Its true legacy is as a benchmark for the era’s limitations. Later digital Sudoku platforms (websites like Web Sudoku, mobile apps like Sudoku.com) would iterate on its foundation by adding social features, adaptive difficulty, beautiful themes, and seamless device sync. Desktop Sudoku represents the last gasp of the isolated, single-player, boxed-software puzzle for the PC. It captures the moment when the demand for puzzles outstripped the supply of sophisticated digital clients, leading to a proliferation of simple, functional tools. It is a historical artifact of the transition from print to digital, embodying the initial, ungainly step where the digital version was a direct, feature-poor mimic of its paper ancestor.

Conclusion: The Unassuming Artifact

Desktop Sudoku is not a game one would typically “review” in a traditional sense. It lacks the narrative, spectacle, or mechanical ambition to stand alongside the acclaimed titles of 2005 listed in the Metacritic and Wikipedia sources—titles like Resident Evil 4, Civilization IV, or Shadow of the Colossus. Yet, its historical value is precisely in its lack of aspiration.

It is a digital fossil, perfectly preserving the aesthetics, constraints, and market dynamics of the mid-2000s casual-puzzle boom. It demonstrates how a global cultural phenomenon is initially serviced not by visionary developers, but by a swarm of pragmatic software solutions meeting a basic need. Its value is archaeological. To examine Desktop Sudoku is to understand the moment when the logic puzzle fully migrated to the personal computer not as a game, but as a ubiquitous desktop utility—a precursor to the infinite, algorithmically-generated puzzle libraries of today, delivered with none of the modern polish but all of the essential functional integrity.

Final Verdict: As a game, Desktop Sudoku is negligible. As a historical document of the 2005 Sudoku craze and the last era of the standalone desktop puzzle application, it is an utterly representative and thus profoundly informative specimen. It earns a place in history not for what it achieved, but for what it so plainly was: a quiet, functional cog in a massive, fleeting cultural machine.