- Release Year: 1982

- Platforms: 4A, Antstream, Apple II, Arcade, Atari 2600, Atari 5200, Atari 7800, Atari 8-bit, BlackBerry, BREW, Casio PV-1000, Commodore 64, FM-7, Game Boy Advance, Game Boy, Intellivision, J2ME, MSX, NES, Nintendo 3DS, Nintendo Switch, Palm OS, PC-6001, PC-8000, PC-88, PC Booter, PlayStation 4, Sharp MZ-1500, Sharp MZ-700, Sharp MZ-800, Sharp MZ-80K, Sharp X1, Sord M5, TI-99, VIC-20, Wii U, Wii, Windows, Xbox 360, Xbox One, Windows Mobile

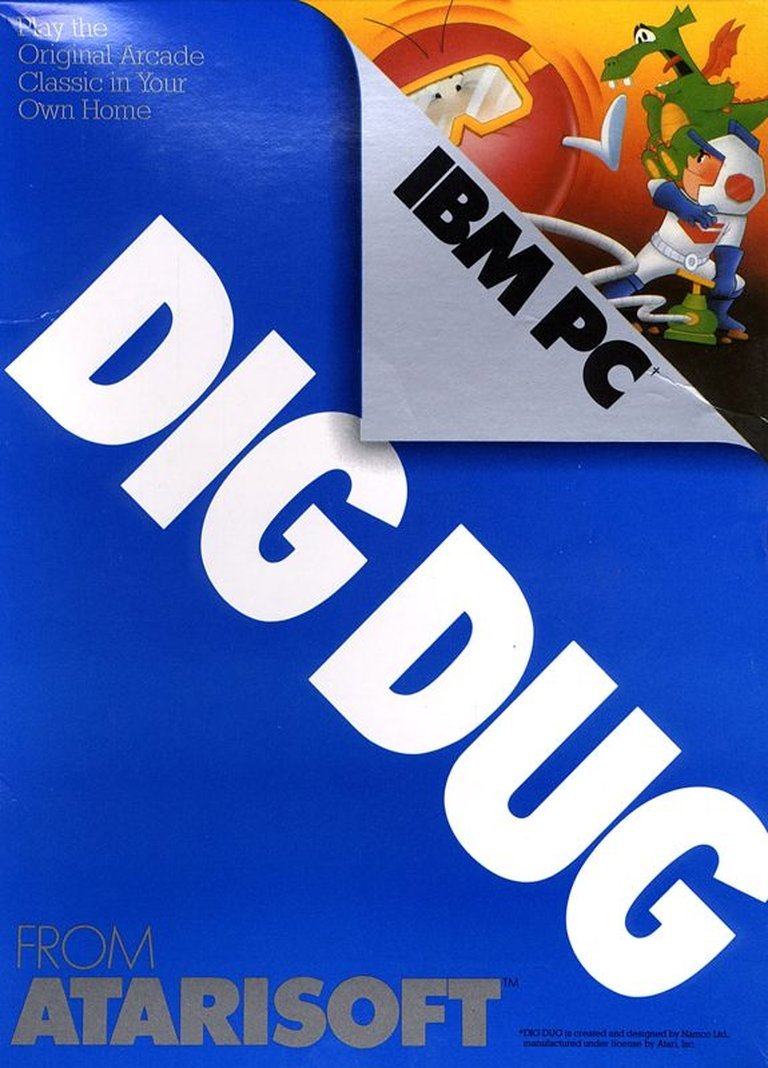

- Publisher: Atari Corporation, Atarisoft, Bandai Namco Entertainment America Inc., Bandai Namco Games Inc., Bug-Byte Software Ltd., Casio Computer Co., Ltd., Datasoft, Inc., Dempa Shimbunsha, Hamster Corporation, INTV Corp., Namco Bandai Games Europe SAS, Namco Limited, Namco Mobile, Namco Networks America Inc., Nintendo Co., Ltd., Stambouli Frères S.A., TAKARA Co., Ltd., Thunder Mountain

- Developer: Bandai Namco Studios Inc., Namco Limited

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade

- Average Score: 47/100

Description

Dig Dug is a classic arcade action game released in 1982, where players control an underground digger navigating a cross-section of earth to eliminate enemies like Pookas and Fygars by inflating them with a pump until they burst or crushing them with falling rocks. Set in procedurally dug tunnels, the game challenges players to strategize routes, avoid fire-breathing dragons, and collect bonus vegetables while managing escalating enemy speeds across multiple stages in this single-player or alternating two-player experience.

Gameplay Videos

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (65/100): old school never looked so good.

imdb.com (30/100): initially creative killfest is never going to end until you succumb to frustration or quarter poverty.

Dig Dug: Review

Introduction

In the neon-lit arcades of the early 1980s, amid the pixelated frenzy of Pac-Man chomping pellets and Space Invaders descending from the skies, one game emerged as a quirky underground revolution: Dig Dug. Released in 1982 by Namco and distributed in North America by Atari, this unassuming maze title transformed simple digging into a symphony of strategy, tension, and explosive satisfaction. As a professional game journalist and historian, I’ve revisited countless classics from the golden age of arcades, but Dig Dug stands out for its audacious premise—a lone miner battling subterranean beasts with nothing but a pump and his wits. It’s a testament to how minimalism can birth profound engagement, turning a single screen into a canvas of emergent chaos.

Dig Dug’s legacy endures not just as a commercial juggernaut—grossing over $520 million in arcade earnings worldwide in its debut year—but as a pioneer of player agency in maze games. Unlike the rigid paths of Pac-Man, Dig Dug empowered players to sculpt their own labyrinths, flipping the script from evasion to aggression. My thesis is straightforward yet profound: Dig Dug isn’t merely an arcade relic; it’s a masterful blueprint for interactive design, blending tactile satisfaction, layered strategy, and whimsical horror into a formula that influenced generations of games, from Boulder Dash to modern roguelikes like Spelunky. Forty years on, it remains a dig worth taking, unearthing joys that feel as fresh as freshly turned soil.

Development History & Context

Dig Dug’s creation was a product of Namco’s golden era, a time when the Japanese developer was riding high on the successes of Pac-Man (1980) and Galaga (1981), titles that redefined arcade accessibility and spectacle. Founded in 1955 as Nakamura Seisakusho, Namco had evolved into a powerhouse of coin-op innovation by the early 1980s, blending Japanese precision engineering with playful creativity. The game was spearheaded by Masahisa Ikegami, a visionary designer who sought to break from Pac-Man’s chase mechanics. Ikegami’s core inspiration? A childhood memory of pumping up a bicycle tire, wary of over-inflation’s explosive consequences. This personal anecdote birthed Dig Dug’s signature weapon: an air pump that turns enemies into bloating, vulnerable balloons, adding a rhythmic, almost therapeutic layer to combat.

Assisting Ikegami was Shigeru Yokoyama, the acclaimed creator of Galaga, whose expertise in enemy patterns and scoring systems infused Dig Dug with escalating tension. The programming duo of Toshio Sakai and Shōichi Fukatani handled the heavy lifting on Namco’s Galaga arcade board—a cost-effective choice that reused hardware from hits like Galaga and Bosconian (1981). This board’s capabilities allowed for smooth side-view scrolling and real-time tunnel generation, though it imposed constraints like fixed-screen layouts to manage processing power. Yuriko Keino, in her debut as a composer, crafted the game’s iconic soundtrack; at executives’ insistence for a “walking sound,” she improvised a jaunty melody that plays only during movement, creating an uncanny rhythm that underscores the player’s every step. Artist Hiroshi “Mr. Dotman” Ono designed the sprites, drawing Taizo Hori (Dig Dug’s true name, a pun on the Japanese “horitai zo,” meaning “I want to dig”) as a Smurf-like figure—small, blue, and helmeted—to evoke cartoonish charm, though exterior cabinet art humanized him to dodge potential lawsuits.

The technological landscape of 1982 was unforgiving: arcade machines ran on 8-bit processors with limited RAM, demanding efficient code to handle dynamic dirt excavation without frame drops. Namco’s vision emphasized offense over defense, allowing players to “design their own maze” in contrast to Pac-Man’s preordained paths. This was radical amid a market saturated with shooters and eaters; competitors like Universal’s Mr. Do! (1982) would later clone the digging fad, but Dig Dug’s pump mechanic set it apart. Released in Japan on February 20, 1982, it hit North American arcades in April via Atari’s licensing deal, capitalizing on the post-Pong boom. Marketing positioned it as a “strategic digging game,” with Atari’s aggressive promotion—including a bizarre 1982 commercial—propelling it to over 380,000 units sold globally in its first three years. In a landscape dominated by Atari’s own titles like Asteroids, Dig Dug exemplified the cross-cultural pollination that fueled the arcade explosion, bridging Japanese ingenuity with American distribution muscle.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Dig Dug’s “narrative” is as subterranean as its setting—minimalist, almost absent, yet pregnant with thematic depth that rewards scrutiny. There’s no overt plot in the arcade original; manuals offer sparse lore, portraying Taizo Hori as a miner or gardener tasked with purging underground pests threatening Tokyo’s soil (or, in one variant, an alien planet in the UGSF continuity). Enemies—the goggle-wearing Pookas and fire-spewing Fygars—manifest as invasive lifeforms, evoking a 1982 “Dig Dug Incident” where they riddle the earth with holes. This event, canonized in later Namco lore like the Mr. Driller series, positions Taizo as a reluctant hero, single-handedly resolving the crisis and founding the Driller’s Association to regulate such threats.

At its core, Dig Dug explores themes of intrusion and reclamation. Taizo, a diminutive everyman in a pressurized suit, embodies human persistence against nature’s (or monster’s) encroachment. The act of digging isn’t mere traversal; it’s territorial conquest, turning solid earth into player-forged tunnels that symbolize agency over chaos. Pookas, named after the Japanese onomatopoeia “puka puka” for inflation, represent insidious ubiquity—they phase through dirt as ghostly eyes, embodying paranoia and the unseen dangers lurking beneath the surface. Fygars, the more aggressive dragons, add elemental fury with their horizontal fire blasts, thematizing raw power and the peril of direct confrontation. Their behaviors evolve: early rounds see them idle, but as stages progress, they chase relentlessly or flee to the surface, mirroring a survival instinct that humanizes these pixelated foes.

Thematically, Dig Dug subverts arcade tropes. Where Pac-Man is a frantic fugitive, Taizo is the aggressor, his pump a phallic, absurdly non-violent weapon that bloats enemies into comical orbs before their messy demise. This inflation mechanic delves into excess and vulnerability—pump too much, and they burst in a spray of pixels; interrupt, and they deflate, stunned but resilient. It’s a metaphor for overreach, echoing 1980s anxieties about environmental invasion (Pookas as urban sprawl pests?) or personal inflation (greed leading to downfall). Bonus vegetables, sprouting after dropping two rocks, inject whimsy, rewarding thorough excavation with escalating prizes: carrots in round one, pineapples by round 10. No dialogue exists, but the game’s rhythm—Taizo’s jaunty walk-tune halting in stillness—narrates tension through silence, making every decision feel like a pulse in a living, breathing underworld.

In broader canon, Dig Dug ties into Namco’s universe: Taizo fathers Susumu Hori of Mr. Driller, marries (and divorces) Baraduke’s Masuyo Tobi, and cameo in titles like Pac-Man World. This retroactive lore elevates the original’s sparseness into a foundational myth, transforming a score-chasing arcade jaunt into an origin story of heroic drilling. Thematically, it’s a celebration of ingenuity over brute force—Taizo’s tools triumph through patience and planning, a quiet rebuke to the era’s bombastic shooters. Yet, beneath the cuteness lurks horror: the kill screen at round 256, where a Pooka spawns inescapably atop Taizo, evokes inevitable doom, a pixelated Sisyphus trapped in eternal excavation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Dig Dug’s brilliance lies in its deceptively simple core loop, elevated by interlocking systems that demand foresight and adaptability. At heart, it’s a single-screen maze-builder: Taizo starts at the surface left, descending into a cross-section of diggable dirt riddled with rocks and enemies. The primary action—digging—occurs in real-time, creating tunnels that serve dual purposes: mobility and trap-setting. Unlike static mazes, every excavation reshapes the battlefield, turning solid earth into navigable voids while scoring minor points for thoroughness (up to 1,000 per fully cleared screen). This emergent design fosters replayability; a hasty dig might trap foes, but poor planning invites ambushes.

Combat revolves around two methods: inflation and crushing. The air pump, activated by a single button, extends a harpoon-like hose that latches onto adjacent enemies, freezing them. Rapid button presses inflate Pookas or Fygars—red spheres or green serpents—into swelling forms, culminating in a 200-500 point pop (scaling by size). Mechanics introduce risk: pumping takes 8-10 inputs for full burst, leaving Taizo vulnerable; detach prematurely, and the foe deflates stunned, potentially luring others into a kill zone. Fygars add peril with horizontal fire blasts (every 2 seconds if facing Taizo), forcing vertical dodges or side-flank attacks for bonus points (600 vs. 400 from below). Pookas, meanwhile, phase through dirt as ethereal eyes after 10 seconds out of sight, bypassing walls for ghostly pursuits— a genius AI wrinkle that punishes line-of-sight neglect.

Rocks introduce strategic depth, immovable boulders that wobble when undermined, falling after a delay to crush anything (or anyone) below. A single rock drops for 1,000 points, multiples yield combos (e.g., two Pookas: 2,500), and full clears via rocks net 3,000+. Dropping two rocks per stage spawns a central vegetable bonus—carrot (100 points) to swan (10,000 in round 84)—timed to vanish, encouraging risk. Enemies ramp up: rounds 1-4 have 1-2 foes; by round 50, screens swarm with six, faster and more evasive. The last survivor flees upward, ghosting through dirt to escape unpunished (no points), injecting urgency.

UI is minimalist: score, lives (three starts, extras at 10,000/50,000/100,000), and round indicator via surface flowers. Controls—directional joystick and pump button—are responsive, though ports vary (e.g., Atari 2600’s sluggishness). Progression spans 255 rounds, with dirt hues shifting (brown to purple) and enemy speeds doubling periodically. Flaws emerge in later ports: some omit animations (no inflating visuals on Apple II), or alter physics (slower falls on C64). Yet the original’s loop innovates: no power-ups, just tools and terrain, making every death a lesson in pathing. Innovative systems like ghost-phasing prefigure Metroidvania exploration, while scoring incentives (consecutive ghosts: 800+) reward mastery. Flawed in isolation—repetitive without variety— but sublime in synergy, Dig Dug’s mechanics forge addiction from calculation, where one misplaced dig spells doom.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Dig Dug’s world is a claustrophobic underworld, a single-screen diorama of stratified dirt evoking a geological cross-section—brown loams giving way to ochre sands and violet clays in later rounds. This vertical slice of earth isn’t static; player agency carves it anew each stage, transforming blank canvas into labyrinthine veins that pulse with danger. Atmosphere builds through isolation: the surface, dotted with flowers signaling rounds (one for stage 1, multiples later), hints at a vibrant above-world Taizo protects, while below lies primordial threat. Rocks jut like ancient sentinels, vegetables bloom as fleeting oases, creating a ecosystem of peril and reward. It’s intimate world-building—no sprawling maps, but a microcosm where every tunnel echoes isolation, amplified by enemies’ ghostly transits through “solid” barriers, blurring safe haven and invasion.

Art direction, by Hiroshi Ono, is pixel poetry: Taizo’s compact sprite—bespectacled helmet, pump harness—exudes pluck amid menace. Pookas’ tomato-red rotundity and oversized goggles lend cartoonish menace, their eye-only ghosts a stroke of minimalist horror. Fygars coil like emerald question marks, fire a blazing horizontal lash, their segmented bodies adding fluidity. Palette constraints yield charm: arcade’s 16 colors pop vibrantly, dirt textured with subtle shading. Ports diverge—Atari 2600’s blocky rocks and frog-like Fygars sacrifice detail for playability, while NES emulates arcade fidelity with animated pumps. Visuals contribute immersion: inflating foes swell grotesquely, rocks crumble satisfyingly, fostering a tactile “feel” of excavation despite 2D limits.

Sound design, Yuriko Keino’s debut, is auditory genius in scarcity. No looping BGM; instead, Taizo’s walk triggers a bouncy four-note jingle (“da-da-da-dum”), halting in stillness to heighten vulnerability—brilliant tension-building, evoking creeping dread. Enemy contacts blare a shrill “pop” for inflations, a thudding “squish” for crushes; Fygar’s fire hisses menacingly. Vegetable pickups chime progressively (simple tones escalating to fanfares), rewarding progression. Arcade’s chiptune purity shines, though ports vary: C64’s SID chip amplifies melodies lushly, Atari 2600 distorts them quaintly. Collectively, art and sound craft a whimsical yet claustrophobic vibe—cute sprites mask survival horror, the melody’s rhythm syncing with digging’s pulse, making the underground a living, breathing antagonist that pulls players deeper.

Reception & Legacy

Upon launch, Dig Dug exploded onto the arcade scene, cementing its status as a 1982 powerhouse. In Japan, it ranked second in Game Machine’s annual earnings, trailing only Namco’s Pole Position, with over 22,000 U.S. cabinets sold by Atari that year alone—generating $46.3 million (over $151 million adjusted). Critics hailed its innovation: AllGame awarded 5/5 for the arcade version, praising “quirkily cute characters” and “myriad strategies”; Electronic Fun with Computers & Games gave Atari ports 3.5-4/4 for faithful translations. Blip Magazine lauded its “simple controls and pleasant background music,” while Gamest (1998) enshrined it among arcade greats for subverting “dot-eater” norms. Home ports shone variably: NES’s 80% from HonestGamers for “close to the original”; Atari 2600’s 91% from Video Game Critic for spot-on gameplay despite visuals. MobyGames aggregates 73% critic/3.7/5 player scores, with plaudits for addiction but gripes on repetition (e.g., Eurogamer’s 60% for XBLA’s “coin-gobbling” brevity). Commercial peaks included 58,572 Famicom Mini sales (2004) and 222,240 XBLA downloads (2011), proving enduring appeal.

Reputation evolved from arcade smash to historical cornerstone. Early clones like Mr. Do! (1982) and Boulder Dash (1984) spawned a “digging genre,” with mobile echoes in Dig Dog and SteamWorld Dig crediting its environmental manipulation. Sequels faltered—Dig Dug II (1985) scored lower for its overhead shift—but the Mr. Driller series (1999 onward) revitalized Taizo as a patriarch-hero, linking to Namco crossovers like Namco × Capcom. Re-releases in Namco Museum compilations (e.g., 50th Anniversary, 2005) and Arcade Archives (2016) added leaderboards and HD filters, boosting modern scores (IGN’s 7/10 for XBLA). Influence permeates: Spelunky’s procedural caves, SteamWorld Dig’s excavation puzzles, even Wreck-It Ralph’s cameos nod to its whimsy. Commercially, it inspired slots, webcomics (ShiftyLook’s 2012 series), and lore expansions. Flaws like port inconsistencies (VIC-20’s oversizing) faded against its role in democratizing strategy, shaping roguelites and indies. Dig Dug’s legacy: a quiet innovator, proving simple tools forge endless depths.

Conclusion

Dig Dug endures as a pinnacle of arcade ingenuity, its pump-and-dig alchemy transforming 1982’s technological shackles into timeless joy. From Ikegami’s tire-pump epiphany to Keino’s rhythmic strolls, every element coalesces into a loop of strategic euphoria—excavating peril, bloating foes, and toppling rocks in pixelated catharsis. Narrative sparsity belies thematic riches: reclamation, excess, persistence. Art and sound infuse whimsy into claustrophobia, gameplay layers risk into mastery. Reception affirmed its smash status, legacy spawning genres and revivals that echo its charm.

In video game history, Dig Dug claims an exalted niche: not the flashiest, but the most cleverly subversive, a miner’s pick unearthing arcade’s soul. For historians, it’s essential; for players, eternally replayable. Verdict: An unmissable 9.5/10—pump it up, and it’ll inflate your appreciation for gaming’s roots. If Pac-Man ate the maze, Dig Dug dug it deeper, and we’re all richer for it.