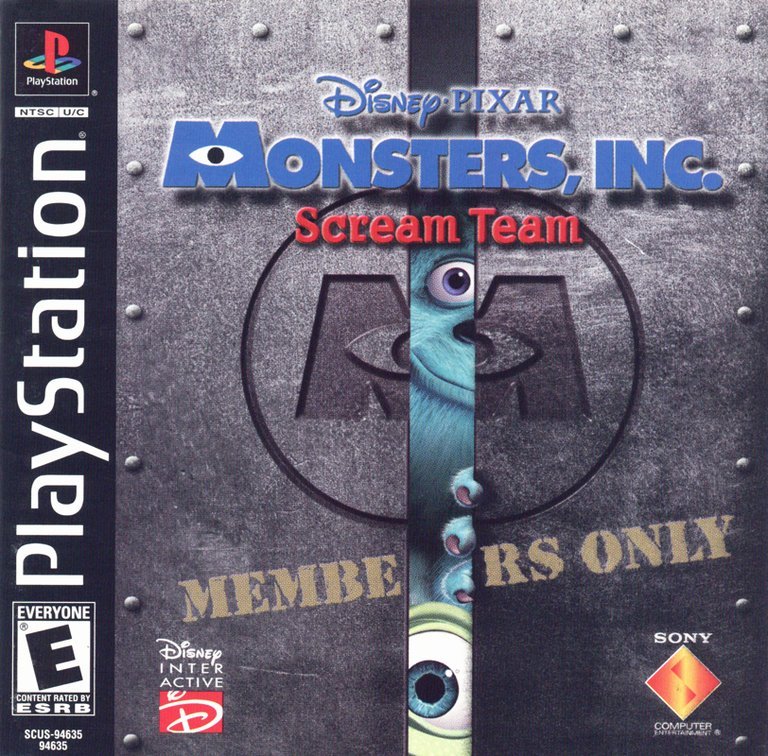

- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: PlayStation 2, PlayStation 3, PlayStation, PS Vita, PSP, Windows

- Publisher: CD Projekt Sp. z o.o., Disney Interactive (Europe, Middle East & Africa) S.A., Disney Interactive, Inc., Disney Interactive, Sony Computer Entertainment America Inc., Sony Computer Entertainment Europe Ltd.

- Developer: Artificial Mind & Movement

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Collecting, Platforming, Scaring

- Setting: Scare Island

Description

Disney•Pixar’s Monsters, Inc.: Scare Island is a 3D action game set in the Monsters, Inc. universe, where players assume the roles of James P. ‘Sulley’ Sullivan or Mike Wazowski on Scare Island to train as Masters of Scare. The gameplay involves collecting monster slime to perform humorous scare tricks on humans across various levels, with authentic voice acting and graphics inspired by the original film.

Gameplay Videos

Disney•Pixar’s Monsters, Inc.: Scare Island Free Download

Disney•Pixar’s Monsters, Inc.: Scare Island: A Scholarly Retrospective of a Forgotten Platformer

Introduction: The Scare Threshold

In the eternal calculus of video game history, licensed titles occupy a curious, often maligned, space. They are frequently dismissed as cynical cash-ins, pale imitations of their cinematicsourcematerial_, destined for bargain bins and collective memory loss. Yet, within this gilded cage, some titles strive for more—they become vessels of affection, attempting to distill a film’s essence into an interactive format. Disney•Pixar’s Monsters, Inc.: Scare Island, released in the waning days of the PlayStation 1’s dominance and the nascent years of its successor, stands as a quintessential case study in this endeavor. It is a game that is neither a profound failure nor a hidden gem, but a meticulously crafted artifact of its time—a product of technological constraints, corporate synergy, and a genuine desire to let children (and the childlike) step into the furry, one-eyed shoes of Mike and Sulley. This review posits that Scare Island is not a masterpiece, but it is a significant, meticulously documented example of early-2000s family gaming, whose reception and legacy reveal the evolving expectations of both players and critics toward adaptations. Its true value lies not in groundbreaking innovation, but in its role as a functional, faithful, and ultimately transitional piece of software that captures a specific moment when 3D platformers were the dominant genre for all-ages entertainment.

Development History & Context: The Canadian Pipeline and the PS1/PS2 Cusp

The Studio and the Vision

The game was developed by Artificial Mind & Movement (A2M), a Montreal-based studio that, in the early 2000s, was rapidly building a reputation as a premier developer of licensed games and work-for-hire projects. Their portfolio from this era reads like a catalog of early-2000s children’s media, including titles like Scooby-Doo! Mystery Mayhem and Disney’s Lilo & Stitch: Trouble in Paradise. A2M was not an auteur studio crafting singular visions; it was a efficient, technical powerhouse specializing in translating pre-existing intellectual property into competent, accessible video games. The vision for Scare Island was therefore dictated less by a singular creative lead and more by the dual imperatives of Disney Interactive and Sony Computer Entertainment: create a game that was (a) recognizably Monsters, Inc., (b) accessible to a young audience, (c) technically viable on current hardware, and (d) could be developed on a timeline synced with the film’s home media release window.

Technological Constraints and Platform Strategy

The game’s release history is a map of early-2000s platform fragmentation. It debuted on the PlayStation (PS1) in October/November 2001, followed by a Windows port in early 2002, and a PlayStation 2 version shortly thereafter. This strategy was common for licensed titles aiming for maximum market penetration. The PS1 version, pushed to the absolute limit of the aging hardware, represents the core experience. The PS2 version, as noted by several critics (e.g., MAN!AC, Gamesmania.de), is ironically often a less stable port, suffering from frame rate issues that belie its more powerful hardware—a common pitfall of rushed cross-generation development.

Technologically, the game was built using the RenderWare engine (as confirmed by Wikipedia), a versatile middleware solution that was becoming an industry standard for its ability to deploy 3D graphics across multiple platforms (PS1, PS2, Windows) with a single codebase. This practicality came at an aesthetic cost. The PS1’s hardware struggled with complex 3D environments, leading to the “blocky polygons” and “blurry, generally crappy” textures lamented by player reviewer phlux. The character models, while recognizable, lack the fluid, expressive animation of their Pixar counterparts—a impossible bar for the era’s real-time 3D, but a stark contrast that disappointed players. The game’s visual identity is one of functional 3D platforming aesthetics: bright, primary colors, simple geometry, and a fog-of-war or distance-culling technique to hide draw-in and low-poly counts. It is a game defined by its hardware’s limits.

The Gaming Landscape of 2001-2002

The late 2001/early 2002 window was a watershed moment. The PS2 had launched, but its library was still thin. The PS1, however, was in its twilight, saturated with platformers (Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy arrived in December 2001, setting a new visual benchmark). The family/kids’ game space was dominated by three pillars: Naughty Dog’s Crash Bandicoot series (still PS1-exclusive), Insomniac’s Ratchet & Clank (PS2, December 2002), and the ubiquitous Disney licensed titles. Scare Island entered this arena not as a innovator, but as a competent, movie-tie-in competitor. It lacked the polish of a first-party Sony title but offered something those games did not: authentic voice acting and direct cinematic tie-ins. In this context, its primary competition was not Jak and Daxter, but other film adaptations like Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (also 2001), which shared a similar design philosophy: safe, accessible 3D exploration for a guaranteed audience.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Training Simulation as Narrative

The film Monsters, Inc. is a story about corporate scandal, child endangerment, and the deconstruction of a societal myth. Scare Island, in a fascinating and telling narrative choice, eschews the film’s plot entirely. There is no Randall, no Boo, no lawsuit, no energy crisis. Instead, the game presents a pure training simulation.

Plot and Setting

The premise, as outlined on MobyGames and Wikipedia, is that Mike and Sulley are hand-picked by Henry J. Waternoose to attend a “private training facility” on Scare Island. This is not the Monsters, Inc. factory, but a specialized, island-based boot camp. This narrative device is brilliant from a game design perspective: it justifies the level-based, mission-oriented structure. Each area (Urban, Desert, Arctic Training Grounds) is a controlled “scenario” where the monsters practice on non-threatening “robot children” called Nerves. The stakes are lowered from “saving the city” to “earning a Top Scarer medal,” making failure consequence-free and perfectly suited for a younger player.

Characters and Dialogue

The game’s greatest narrative strength is its use of the original film’s voice cast. John Goodman (Sulley), Billy Crystal (Mike), James Coburn (Fritz), and others reprise their roles. This is not just an asset; it is the primary narrative connective tissue. The character of Roz, the no-nonsense supervisor, hosts the opening orientation, instantly grounding the player in the film’s world. Supporting characters like Celia Mae (the receptionist with the visible eye) and Randall Boggs appear in cameo roles (the latter in unlockable race challenges), but they are peripheral. The story is a series of vignettes connected by the goal of becoming a “Master of Scare.” The humor is derived directly from the film’s character dynamics—Mike’s neuroticism and Sulley’s gentle giant persona—and is delivered through short, in-level barks and cutscenes.

Thematic Analysis

Where the film explores themes of truth versus lies, child vulnerability, and corporate ethics, the game explores mastery, repetition, and resource management. The core theme is procedural competence. The player is not questioning the system (scaring children for energy); they are learning to perfect it. The “Nerves” are emotionless robot children, removing the film’s moral complexity. Scaring is not an act of terror, but a sport, a game. The “Primordial Ooze” resource strips the act of its existential dread, turning it into a collectible meter. This is a thematically safe, sanitized version of the Monsters, Inc. universe, perfectly aligned with a “Everyone” ESRB rating. It reflects a common trait in children’s media adaptations: the extraction of aesthetic and comedic IP while discarding narrative complexity. The game’s world is one of fun challenges and funny animations, not existential crisis.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Scare Loop

Scare Island is a 3D action-platformer with a unique, resource-based core mechanic that defines its entire structure.

Core Gameplay Loop

The fundamental cycle is: Explore Level -> Collect Primordial Ooze -> Locate & Scare Nerves -> Earn Medals -> Repeat.

1. Exploration & Platforming: Levels are large, open-ended environments (city park, desert canyon, icy lake) with multiple paths, hidden areas, and verticality. Basic platforming (jumping, climbing ledges) is required to navigate.

2. Resource Collection: Primordial Ooze is scattered throughout levels in small vials or larger pools. This is the currency of scaring. Without sufficient ooze (measured by a canister meter), a scare attempt will fail, and the Nerve will laugh at the player.

3. The Scare Mechanic: This is the game’s signature. Approaching a Nerve from the front triggers a button-mashing combo sequence (typically alternating face buttons). The monster performs a preset, humorous scare animation (Sulley might roar and flex, Mike might shout and spin). Success fills the “Fright Meter” (color-coded to the Nerve). If the meter empties or the player laughs (from taking damage), the attempt fails.

4. Medal System & Progression: This is the game’s primary structure.

* Bronze Medal (Level Complete): Scare 5 of the 8 Nerves in a level. Unlocks a movie clip.

* Silver Medal: Collect 10 “Monsters, Inc.” Tokens (hidden collectibles).

* Gold Medal: Scare all 8 Nerves.

* Progression Gating: Obtaining all four Bronze medals in a training ground (e.g., all 4 Urban levels) unlocks a “hidden item” (often a special ability or key) that allows access to previously unreachable areas in other levels, encouraging replay.

Character Differentiation

Choosing between Sulley and Mike is not merely cosmetic.

* Sulley is stronger. His scare combos are more powerful, filling the Fright Meter faster. He is the brute-force option.

* Mike is more agile. He may jump higher or have faster movement speed, but his scares are weaker, requiring more ooze or longer combos. The loading screen hints which character is “recommended” for a level, creating a light puzzle element: do you need Sulley’s power for a distant platform, or Mike’s agility for a tight space?

Innovation and Flaws

* Innovative Twist: The integration of a resource-gathering mechanic directly into the core “combat” was somewhat novel for a kids’ platformer. It added a layer of strategy—rushing to scare without ooze is futile. The medal system, with its gold/silver/bronze tiers, was a early precursor to the “objective completion” systems that would become standard in platformers like Super Mario 64.

* Systemic Flaws:

* Repetition: The core loop is undeniably repetitive. As noted by multiple critics (Game Informer, Jeuxvideo.com, player phlux), scaring eight identical Nerves per level with the same 3-4 combo animations becomes a grind. The 12 main levels (3 grounds x 4 areas) with 8 Nerves each means the player must perform the scare action a minimum of 144 times, not including failed attempts or medal hunting.

* Camera & Control Issues: The 3D camera is a frequent point of criticism (Computer Bild Spiele, Gamekult). Automatic camera angles often fight the player during precise jumps, making platforming more frustrating than it should be. Controls can feel “stiff” (as per Retro Replay), especially in high-pressure scare sequences.

* Pacing & Checkpoints: Levels are large, but death often results in significant backtracking. Checkpoints are sparse, amplifying frustration.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Faithful, Flawed Facsimile

Visual Design and Atmosphere

The game’s world is a stylized, cartoonish interpretation of the film’s aesthetic, filtered through the lens of PS1-era 3D limitations. The Urban, Desert, and Arctic Training Grounds provide clear visual variety, but they are generic archetypes (city park, canyon, frozen lake) rather than specific, memorable locations from the film (like the Scare Floor or the Door Vault). The color palette is bright and primary, avoiding the darker tones of the film. The atmosphere is consistently playful and non-threatening, aligning with the “training simulation” premise. The environments are functional for gameplay—platforms are clearly defined, paths are logical—but they lack the dense, imaginative detail of Pixar’s world. The “Popel-3D-Optik” (as Gamesmania.de derisively called it) is characterized by low-poly models, simple textures, and noticeable fog.

Character Animation and Presentation

This is the game’s most contentious area. The character models are recognizable but crude. Sulley’s fur is represented by a blue texture with a slight bump mapping effect; it is nowhere near the simulation of individual hairs seen in the film. Mike’s spherical body and single large eye are captured, but his expressive squash-and-stretch animation is completely absent. The scare animations, while “funny” and “hilarious” (Impulse Gamer) at first, are limited, repeated, and lack the fluid, physical comedy of Pixar’s animation. The * cinematic cutscenes, however, are a high point. They use in-game graphics but are directed with more camera movement and often incorporate *actual movie clips (unlocked via medals), which are a stark and welcome contrast, reminding the player of the source material’s quality.

Sound Design and Voice Acting

This is the game’s undisputed triumph and its greatest saving grace. The use of the original film voice cast is not a mere cameo; it is a foundational element. Roz’s deadpan delivery, Mike’s rapid-fire anxiety, Sulley’s rumbling reassurance—all are present and accounted for. This audio authenticity does immense heavy lifting for the game’s charm and sense of place. The soundtrack is a competent, if generic, orchestral score that mimics Randy Newman’s style without having his melodic wit. Sound effects for jumping, collecting ooze, and scaring are clear and satisfying. The voice work elevates the entire experience, making the repetitive gameplay more palatable through sheer association with beloved characters.

Reception & Legacy: A Game of Two Halves

Critical Reception at Launch

Aggregate scores paint a picture of “mixed” or “average” reception (Metacritic PS1: 65/100, MobyGames Avg: 66%). The critical consensus was remarkably consistent, split along two axes:

- The Pro-Family, Pro-Accessibility Camp: Reviews like GameZone (90%), KidZone (88%), and Absolute Playstation (87%) praised its simple controls, non-violent premise, and faithfulness to the film’s spirit. They saw it as an excellent, safe title for children and families. IGN (75%) noted its surprising enjoyability despite low expectations, calling it a “must buy for any parent looking for a non-violent, fun, challenging, puzzle game.”

- The Disappointed Technical/Gameplay Camp: Reviews like GameSpot (54%), Game Informer (50-65%), PC Games (Germany) (52%), and Gamesmania.de (55%) criticized its graphics, repetition, and lack of depth. Game Informer succinctly stated, “The bad thing about Disney games is that they’re all so similar… It looks like butt.” 4Players.de was scathing, calling it a “nur was für fanatische Disney-Fans!” (only for fanatical Disney fans), criticizing the “eintöniger Verlauf” (monotonous progression) and weak graphics even for the PS2.

The player review gap is telling. The two available player reviews on MobyGames are polar opposites: one condemning it as an “unnecessary franchise” with “crappy” graphics and animations, the other calling it “a great game for kids” with “perfect” graphics for its time. This reflects the fundamental divide in perspective: judging it as a standalone game versus judging it as a piece of licensed fan service.

Evolution of Reputation and Legacy

Scare Island has not undergone a significant critical reevaluation. It remains a niche title, remembered primarily by:

* Nostalgic adults who played it as children, often citing its simplicity and voice acting fondly (as seen in My Abandonware comments: “the first game i remember ever playing”).

* Collectors of Disney/Pixar games.

* Retro enthusiasts exploring the breadth of PS1/PS2 libraries.

Its legacy is one of archetypal execution. It represents the peak of a specific design philosophy: the “easy-to-pick-up, hard-to-put-down” 3D platformer for a general audience, built on a strong IP license. It did not influence the broader industry; instead, it was influenced by and contributed to the market saturation of such titles. Its use of the RenderWare engine was common, not pioneering. Its structure—collect-a-thon, medal-based progression—was standard (Banjo-Kazooie, Donkey Kong 64). Its place in history is as a competent, mid-tier product in Disney Interactive’s prolific early-2000s output, which also included titles like The Lion King 1½ and Atlantis: The Lost Empire. It solidified the template that would be used for countless adaptations for the next decade: prioritize audio authenticity, simplify gameplay, and accept graphical mediocrity due to budget and time constraints.

Conclusion: The Verdict on Scare Island

Disney•Pixar’s Monsters, Inc.: Scare Island is not a forgotten classic. It is a competently assembled piece of branded entertainment that successfully translates the characters, humor, and premise of its source material into a functional, if repetitive, 3D platformer. Its triumphs—the stellar voice acting, the clear (if simple) level goals, the accessible controls—are precisely what its target audience (children aged 6-10) would have appreciated in 2001. Its failures—the dated graphics, the monotonous scare loop, the finicky camera—are the inevitable compromises of its budget, its engine, and its tight development cycle.

As a historical artifact, it is fascinating. It captures the moment when 3D platformers were the default genre for IP-based kids’ games, just before the genre began to wane in popularity. It demonstrates the pragmatic realities of cross-platform development (RenderWare, PS1/PS2 parity). It reveals the priorities of licensed game development at the time: audio fidelity and brand recognition over graphical prowess or deep gameplay.

In the canon of video game history, Scare Island is a footnote, not a headline. Yet, for those willing to examine it closely, it is a perfectly preserved footnote. It tells us that even in an era of “shovelware,” there was a baseline of professionalism and affection for the source material. It is a game that does not aspire to be art, but it aspires to be sufficient. It provides a few hours of simple, recognizable fun, anchored by the comfort of familiar voices. For the historian, its value is in its typicality—it is a clear, well-documented example of how the industry serviced the family market at a specific technological and cultural crossroads. For the nostalgic player, it is a portal back to a time of simpler mechanics and the sheer joy of hearing Mike Wazowski tell you to “Get ready to be scared!” For everyone else, it remains a competent, flawed, and ultimately forgettable simulation of becoming a Master of Scare.

Final Score: 6.6/10 – A functional, faithful, and frequently tedious adaptation that achieves its modest goals but offers little beyond its licensed skin and vocal performances for anyone outside its target demographic. It is a game best remembered for what it represents, not for what it is.