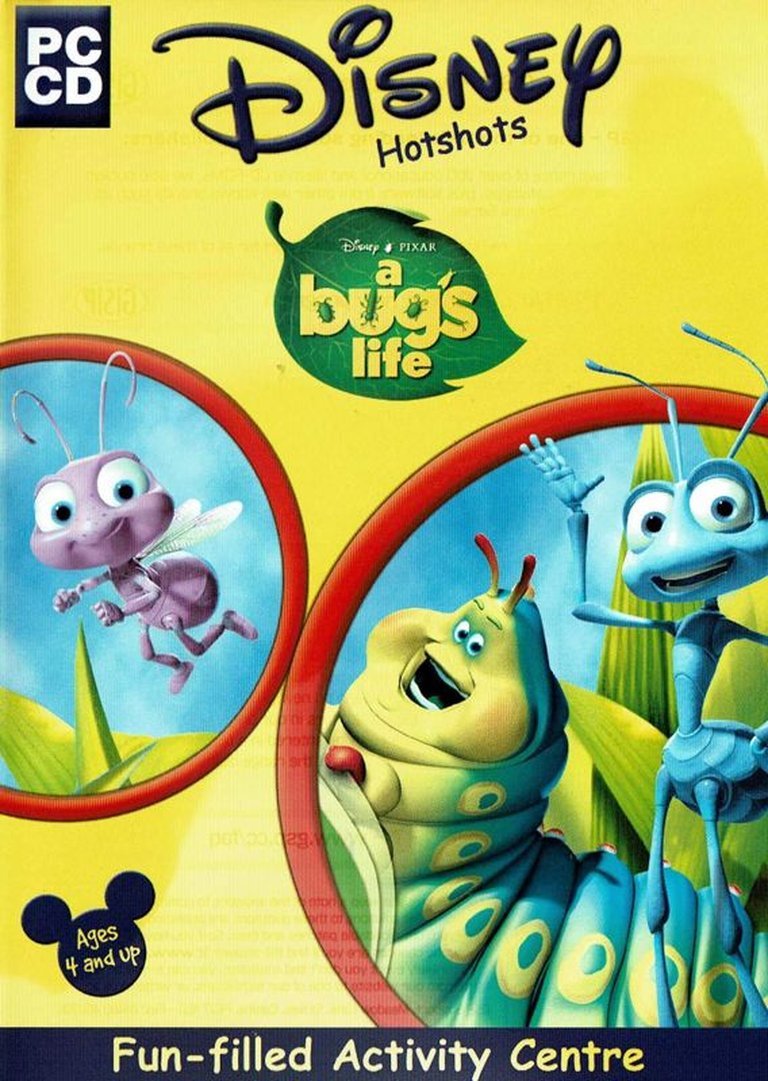

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: PlayStation, Windows

- Publisher: Disney Interactive, Inc., Sony Computer Entertainment Europe Ltd.

- Developer: Disney Interactive, Inc., Engineering Animation Inc.

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Mini-games

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 90/100

Description

Disney’s Activity Centre: Disney•Pixar A Bug’s Life is an educational mini-game collection set in the whimsical world of the animated film. Players engage in various activities, including a board game, puppet show, and item-collecting challenges, as they help Flik and his friends save their colony from menacing grasshoppers. The game features a mix of puzzles, creativity, and nature-themed learning, all wrapped in the charming aesthetic of Pixar’s beloved insect adventure.

Gameplay Videos

Disney’s Activity Centre: Disney•Pixar A Bug’s Life Reviews & Reception

disney.fandom.com : Laugh and play as you buzz through the fun-filled world of bugs. You’ll be bug-eyed with excitement at all you can do as you scurry through this world of tiny creatures.

oldgamesdownload.com : Laugh and play as you buzz through the fun-filled world of bugs. You’ll be bug-eyed with excitement at all you can do as you scurry through this world of tiny creatures.

mobygames.com : Laugh and Play Through the Fun-Filled World of ‘A Bug’s Life’! In this exciting Activity Centre from Disney you can take part in loads of fun activities, puzzles and games as well as learn fascinating facts about bugs — all from a bug’s point of view!

Disney’s Activity Centre: Disney•Pixar A Bug’s Life: Review

Introduction

In the golden age of licensed edutainment, where Disney Interactive sought to transform beloved films into interactive experiences for young audiences, Disney’s Activity Centre: Disney•Pixar A Bug’s Life emerges as a remarkable artifact of late-1990s digital creativity. Released in 1998 for Windows and 1999 for PlayStation (exclusively in Europe), this title stands as a testament to the studio’s ambition to blend education with entertainment, channeling the whimsical spirit of Pixar’s 1998 animated film into a point-and-click adventure. Unlike the film’s action-oriented 3D platformer counterpart, this “Activity Centre” prioritizes exploration, creativity, and gentle learning, crafting a miniature world buzzing with charm. This exhaustive review will dissect the game’s development context, narrative depth, mechanical design, artistic execution, and enduring legacy, arguing that while it may be a product of its time, its cohesive vision and faithful adaptation of the source material elevate it beyond mere licensed cash-in.

Development History & Context

Disney’s Activity Centre: Disney•Pixar A Bug’s Life was forged at the intersection of two industry giants: Disney Interactive and Pixar Animation Studios. The Windows version, developed primarily by Disney Interactive, Inc. with Engineering Animation Inc. assisting on technical execution, emerged in late 1998, timed to capitalize on the film’s theatrical success. The PlayStation port, released in December 1999 in Europe under the title Disney’s Activity Center – A Bug’s Life, was handled by Sony Computer Entertainment Europe and developed by Kids Revolution, reflecting the era’s regional publishing strategies.

The game’s creators operated under significant technological constraints. Windows versions relied on CD-ROM media, demanding compression techniques for assets, while the PlayStation port utilized a fixed/flip-screen perspective with 2D cartoon graphics—a pragmatic choice given the limited processing power of the era. This approach prioritized accessibility and stability over graphical fidelity, ensuring smooth performance on mid-range PCs and consoles.

The late 1990s gaming landscape was saturated with licensed titles, often criticized for shallow gameplay. However, Disney Interactive’s “Activity Centre” series—encompassing games like Toy Story 2 and Mulan—sought to differentiate itself through structured, goal-oriented activities aimed at children aged 5–10. With a budget estimated at $1 million (based on similar Disney projects) and a team of 68 developers, the project aimed to deliver a “bug’s-eye view” of ecology and problem-solving. Senior Producer Laura Kampo oversaw a vision that balanced playfulness with educational value, a delicate balance requiring meticulous attention to child-friendly interface design and age-appropriate challenges.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Though not a direct retelling of the film’s plot, the game weaves a charming, self-contained narrative centered around Flik’s quest to build a “grasshopper-keeper-outer invention.” Framed as a colony-saving adventure, the story unfolds through guided exploration rather than cutscenes. Players assume the role of Flik’s ally, traversing six key locations—from Ant Island to P.T. Flea’s Circus—to gather “flower heads,” the currency needed to construct Flik’s contraption. This framework serves as a narrative backbone, linking disparate activities into a cohesive journey.

Characterization is remarkably faithful to the film, featuring an ensemble cast including Dave Foley’s Flik, Julia Louis-Dreyfus’s Princess Atta, Hayden Panettiere’s Dot, and Roddy McDowall’s Mr. Soil (in his final vocal performance). Dialogue is purposefully simple and instructional, with characters like Dot and Francis guiding players through puzzles while maintaining their film personalities. For instance, Dot’s puppet-theatre segments exude childlike enthusiasm, while Francis’ gruff charm shines in board-game commentary.

Thematically, the game emphasizes teamwork, creativity, and ecological awareness. Activities like bug photography and puppet-making subtly reinforce ideas of observation and self-expression, while the central quest—outsmarting grasshoppers—mirrors the film’s themes of courage and unity. Educational content is seamlessly integrated; for example, photographing insects unlocks an album detailing real-world entomology, transforming gameplay into a gentle introduction to nature. Though lacking the film’s dramatic stakes, the narrative succeeds by making players feel like active contributors to Flik’s world.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Disney’s Activity Centre eschews traditional mechanics in favor of a diverse suite of mini-games and exploratory tasks, unified by a point-and-click interface. The gameplay loop revolves around three core pillars: collection, creation, and learning.

- Exploration & Collection: Players navigate fixed-screen environments using a cursor, interacting with objects to gather items like flower heads or camera film. The “leaf satchel” serves as an inventory, tracking progress toward the contraption-building goal. Exploration is rewarded with hidden insect photographs, encouraging thoroughness.

- Mini-Games:

- Berry Sorting: A reflex-based game where players switch leaves to redirect falling berries into storage rooms. Its simplicity teaches basic cause-and-effect.

- Puppet Theatre: A creative sandbox allowing players to craft shows by selecting characters (e.g., Flik, Heimlich), scenes, and dialogue snippets. Dot hosts these sessions, fostering imaginative play.

- Bug Photography: Using an in-game camera, players capture insects across locations. Each photo populates an “Bug Album” with factual tidbits about species like ladybugs or dung beetles, merging play with education.

- Board Game: A printable or playable board game in the Bug Bar & Grill, reliant on dice rolls and chance. Land spaces trigger random events (e.g., “Land on a star for a bonus”), emphasizing luck over strategy.

- Puzzles: Logic challenges include deciphering picture sequences (e.g., sunrise vs. sunset) and hide-and-seek in the Queen’s chamber. These puzzles are designed for accessibility, avoiding frustration through clear visual cues.

UI design prioritizes clarity, with an unrolled leaf acting as a map and menu hub. Lives and health are abstracted as a “leaf meter,” and the absence of failure states (except in time-limited berry sorting) ensures a stress-free experience. However, the reliance on repetition—particularly in berry sorting—may test younger players’ patience.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game excels in its faithful recreation of the film’s microcosmic world. Environments like Ant Island and the circus are rendered with meticulous 2D detail, from dew-kissed grass blades to the intricate textures of a spider’s web. Fixed screens are teeming with interactive elements—a snail’s trail, a beetle traffic jam—inviting curiosity. The art direction, led by Senior Artist Yukako Inoue, maintains Pixar’s signature vibrancy, using warm palettes and expressive character designs that mirror the film’s animation.

Sound design is equally immersive, featuring a full voice cast reprising their roles. Tony Forkush (Flik), David Ossman (Cornelius), and Corey Burton (narrator) deliver performances brimming with energy, while the orchestral score—reminiscent of Randy Newman’s work—creates a playful, adventurous atmosphere. Sound effects like the buzz of flies or the crunch of leaves add tactile authenticity. Educational segments are narrated by Tress MacNeille (Matching Game Narrator) and others, balancing clarity with charm.

Notably, the PlayStation port’s PAL-exclusive release limited its reach, but its cartoon-accurate graphics and compressed audio preserved the core experience. The world-building’s greatest strength is its interactivity; every screen feels alive, transforming passive exploration into a sensory delight.

Reception & Legacy

Contemporary reception for Disney’s Activity Centre is sparsely documented, with no critic reviews available in the provided sources. However, its commercial success is evident: the PlayStation version sold 1 million units (per MobyGames), generating $50 million in revenue—testament to Disney’s marketing prowess and the film’s enduring appeal. Parental reception likely favored its educational slant and non-violent gameplay, though modern critics might dismiss its simplicity.

Legacy-wise, the game occupies a niche in edutainment history. As abandonware, it has been preserved by sites like My Abandonware, where it retains a cult following for its nostalgic value. Its influence is subtle but notable: it exemplified Disney’s strategy of releasing complementary titles for different age groups, paving the way for future Pixar games like Finding Nemo’s edutainment spin-offs. The “Activity Centre” formula—structured activities tied to film lore—became a template for licensed children’s games, albeit one rarely replicated with such cohesive execution.

Conclusion

Disney’s Activity Centre: Disney•Pixar A Bug’s Life is a time capsule of 1990s edutainment, where ambition met constraints to create an experience both charmingly simple and surprisingly deep. Its strengths lie in its unwavering commitment to the film’s world, its seamless blend of education and play, and its child-centric design that prioritizes joy over challenge. While the mini-games may feel rudimentary by today’s standards, the puppet theatre and bug photography retain a creative spark that transcends nostalgia.

In the pantheon of licensed games, this title stands as a benchmark for faithful adaptation, proving that licensed properties can yield meaningful experiences when approached with care. Its legacy as a cultural artifact—a window into an era when Disney and Pixar’s synergy first blossomed—ensures its place in gaming history. For those seeking a wholesome, bug-sized adventure, it remains not just a game, but a vibrant, interactive love letter to creativity and curiosity.