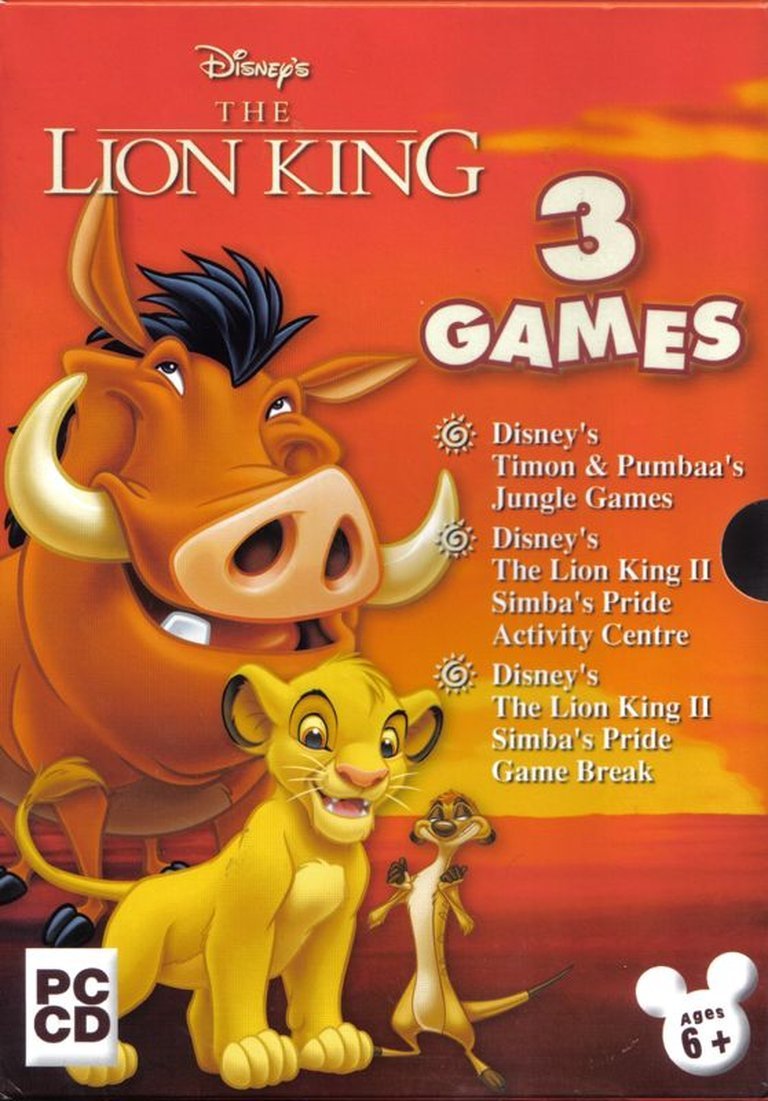

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Disney Interactive

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games is a 2002 Windows compilation released by Disney Interactive, bundling three distinct titles: ‘Disney’s Timon & Pumbaa’s Jungle Games,’ a collection of mini-games featuring the beloved meerkat and warthog duo; ‘Disney’s The Lion King 2 – Simba’s Pride Activity Centre,’ an interactive edutainment experience filled with puzzles and activities; and ‘Disney’s The Lion King 2 – Simba’s Pride Action Game,’ a side-scrolling adventure set in the Pride Lands that follows Kiara’s journey. Released on CD-ROM, the compilation supports keyboard, mouse, and microphone input and offers single-player gameplay rooted in the rich world of Disney’s The Lion King and its sequel.

Where to Buy Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games

PC

Reviews & Reception

vgtimes.com : Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games is a third-person educational game with a mixture of platformer, musical game, puzzle and arcanoid from the developers of 7th Level…

Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games: Review

Introduction: A Forgotten Chapter in Disney’s Digital Safari

In the vast savannah of licensed video games that followed the golden era of 16-bit platforming, few compilations have slipped through the cracks of critical memory quite like Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games. Released in 2002 exclusively for Windows PCs across Europe, this obscure CD-ROM compilation is not just a relic—it’s a rarity, a footnote, and paradoxically, a revealing artifact of a transitional period in Disney Interactive’s long-standing relationship with interactive entertainment.

While its 1994 counterpart—The Lion King for Genesis, SNES, Game Boy, et al.—was a cultural phenomenon, a masterclass in 2D platforming that defined the SNES-era action genre and remains lauded for its impeccable timing, music, and difficulty (adored by millennials and speedrunners alike), the 2002 3 Games compilation is the polar opposite: a quiet, unassuming, and nearly forgotten epilogue to the franchise’s early 2000s multimedia expansion. But what it lacks in hype, it makes up for in historical intrigue.

This isn’t a re-release of classics like the beloved 1994 title. Nor is it a sequel or reimagining. Instead, Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games is a triplet of divergent, educational-adjacent experiences born from the late 90s/early 2000s boom of franchise-licensed activity centers and minigame collections aimed primarily at young children. It represents a pivot away from action-platforming toward interactive edutainment, a shift driven by declining sales in kids’ gaming, the rise of CD-ROM as a budget-stretching medium, and Disney’s broader strategy to monetize franchise extensions beyond just marquee titles.

Thesis: Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games is an overlooked, misunderstood, and deeply symptomatic artifact of early 2000s Disney Interactive—less a “game” in the traditional sense and more a commercialized educational anthology that reveals much about the company’s post-1994 multimedia strategy, the era’s technological limitations, and the forgotten genre of Disney-themed activity software. Its historical value outweighs its entertainment legacy, serving as a crucial bridge between the arcade-style platformers of the 90s and the narrative-driven, storybook-esque edutainment of the 2000s. It is, above all else, a case study in digital franchise expansion—and one worth examining with forensic care.

Development History & Context: The Pivot from Pixels to Print

The Studio: Disney Interactive at a Crossroads

By 2002, Disney Interactive Studios (DIS) was navigating a turbulent shift in the gaming landscape. The company, founded in 1993 to ride the post-Lion King (1994) merchandising wave, had enjoyed early success with titles like Aladdin (1993), The Lion King (1994), and The Jungle Book (1994)—all developed in partnership with internal teams and external partners (e.g., Virgin Interactive, Westwood Studios). These were action-platformers, targeting older kids and general audiences, and they thrived on the limitations of 16-bit hardware, turning tight controls and memorable music into art forms.

But by the late 1990s, the market had changed:

– Home consoles were dominated by 3D tech (N64, PlayStation, later PS2), making 2D platformers feel dated.

– PC gaming was fragmenting; CD-ROMs were used less for pure games and more for educational software, multimedia content, and interactive storybooks.

– Disney’s merchandising engine had shifted toward TV spin-offs (The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride, 1998), Timon & Pumbaa cartoons (1995–1999), and direct-to-video sequels, all of which lacked the cultural weight of the original and demanded interactive extensions to prolong engagement.

Enter Disney Interactive’s pivot to “Activity Centers” and “Jungle Games.” Between 1995 and 2004, the company flooded the PC market with titles such as Disney’s Animated Storybook, Activity Center, Hot Shots, and various Simba’s Pride-themed spin-offs. These were not games in the classic sense—low-budget, Flash-like experiences with minigames, drawing tools, and simple puzzles—but interactive media, designed to keep children engaged with the brand between movie viewings.

The Vision: Franchise Extension Over Gameplay Innovation

Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games was never conceived as a “game” in the traditional sense. It was a multi-title compilation—a bundling strategy born from the realization that standalone activity titles had short shelf lives and limited commercial impact. By packaging three related but distinct experiences into a single CD-ROM, DIS could:

– Maximize content value on a single disc (low production cost, wide compatibility).

– Leverage nostalgia for the original franchise while pushing newer spin-offs (Simba’s Pride, Timon & Pumbaa).

– Target the edutainment niche—this was the era of Reader Rabbit, Carmen Sandiego, and LeapPad, and parents were more receptive to “learning” games for kids aged 3–8.

The three bundled games—Timon & Pumbaa’s Jungle Games, The Lion King 2: Simba’s Pride Activity Centre, and The Lion King 2: Simba’s Pride Action Game—were not developed specifically for this compilation. They were repurposed from earlier stand-alone titles:

– Timon & Pumbaa’s Jungle Games (likely based on or repackaged from earlier PC releases like Disney’s Hot Shots or standalone minigame discs)

– Simba’s Pride Activity Centre (a rebranded version of Disney’s The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride – Active Play, 1998)

– Simba’s Pride Action Game (a simplified platformer or action minigame, possibly a “Game Break” variant, a branding DIS used for short-form action content)

This repackaging strategy exemplifies the era: create once, publish multiple times across compilations. Similar to Classic Game Collections and 2-in-1 releases that followed, 3 Games was about content aggregation, not innovation.

Technological Constraints & the PC Environment of 2002

Crucially, 3 Games was developed for Windows 95/98/ME, an OS in decline but still dominant in home computers in Europe (where it launched). This meant:

– No advanced graphics—raster-based, low-resolution (likely 320×240 or 640×480), sprite-heavy visuals.

– No online features—no multiplayer beyond local split-screen or hotseat turns.

– Heavy use of Flash-style animations, voice clips, and MIDI-like music—common in edutainment titles of the era.

– Input via keyboard, mouse, and even microphone—a rare inclusion (per MobyGames), suggesting some games may have included “singing” or voice-recognition minigames, likely tied to the Swahili or “Circle of Life” musical elements (though unverified, this would align with DIS’s Hot Shots minigames, such as Swampberry Sling and Cub Chase).

The era’s tools (e.g., Macromedia Director, early Flash, custom sprite engines) were designed for presentation over gameplay, prioritizing flashy animations and easy navigation over challenge or complexity. This explains the compilation’s simple, child-friendly UX—click-based menus, narrated instructions, and accessibility-focused design.

The Gaming Landscape: A Blizzard of Minigames

By 2002, the PC edutainment market was flooded with licensed compilations (LEGO, Dinosaurs, SpongeBob SquarePants), many of which followed this “three-in-one” model. 3 Games wasn’t unique in format—it was a meat-in-the-box product, a low-cost, high-margin release aimed at supplementing existing media.

In this context, 3 Games was a tactical, not strategic release—engineered to extend the Lion King brand’s lifespan without the risks (or R&D costs) of a full-fledged sequel or 3D adaptation. It was Disney Interactive’s own version of a “seasonal Blu-ray”—a collector’s convenience item for young households, a cost-effective alternative to physical educational toys.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Circle of Life, Repackaged for Clicks

The Anthology Format: Three Uneven Stories

The compilation’s narrative strength lies not in a unified plot, but in its thematic cohesion through franchise identity. Each of the three games adapts or reimagines material from different corners of the Lion King expanded universe:

-

Disney’s Timon & Pumbaa’s Jungle Games

- Setting: A non-linear, self-contained “Jungle Games” hub inspired by the Timon & Pumbaa (1995–1999) cartoon.

- Characters: Timon, Pumbaa, and guests (Zazu, Melman, etc.) invite players to participate in a variety of minigames, likely including:

- Berry Slingshot (a shoot-’em-up style arkanoid variant, like Swampberry Sling, 1998)

- Mud Splat (a timing-based puzzle game)

- Bug Hunt (a maze or hide-and-seek challenge)

- Balloon Pop (a timing/tapping minigame)

- Theme: “Hakuna Matata” as a philosophy of play and carefree enjoyment. The narrative is minimal—no arc, no progression—but the tone is celebratory, reflecting the Timon & Pumbaa series’ irreverent, comedic spirit.

- Dialogue: Light, repetitive, and full of puns or wordplay (“I’ve got a bug in my system,” “This is a pampered lion!”). Audio clips are recycled from the show or newly-recorded B-rate voice work.

-

Disney’s The Lion King 2: Simba’s Pride Activity Centre

- Source Material: The 1998 straight-to-video sequel The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride, itself a Romeo and Juliet love story between Simba’s daughter Kiara and Scar’s exiled son Kovu.

- Structure: A hybrid activity center—part puzzle, part creative tool, part adventure. Players might:

- Assemble animated scenes from jigsaw puzzles

- “Feed” animals via a mini rhythm game

- Complete “Find the Hidden Animal” challenges with click-based exploration

- Customize artwork with tribal motifs or character silhouettes

- Narrative Framing: Portrayed as a “learning adventure”—players are cast as a junior lion guide helping Kiara and Kovu “earn their spots in the Circle of Life.”

- Themes: Unity, tradition, reconciliation—a watered-down version of the original film’s “circle of life” motif, recontextualized for family boundaries (“Simba’s fear of the past vs. Kiara’s hope for the future”).

- Dialogue: Didactic and moralistic—”We can all be friends,” “Different doesn’t mean dangerous.”

-

Disney’s The Lion King 2: Simba’s Pride Action Game

- Gameplay Hybrid: This is the only “traditional” game—a side-scrolling action-platformer-lite with simple 2D scrolling levels.

- Plot: A mash-up of events from the direct-to-video movie:

- Kiara learns to hunt in the grasslands

- Kovu escapes the Outlands

- The two unite to stop Zira’s coup

- Characters: Kiara (primary playable), Kovu (companion or secondary), Simba (boss or tutorial figure).

- Themes: Rites of passage, coding as initiation—each level involves mastering a new skill: pouncing, roaring, dodging, helping a friend.

- Structure: Non-linear progression with “timed” challenges”—”Race to the watering hole,” “Escape the hyenas,” “Guide Kovu through the thorn maze.”

- Tone: More dramatic than the other two, with music cues from the movie’s orchestral score, but still simplified—no deep character arcs, no Scar-like villainy. It’s myth as minigame.

Thematic Unity: The Childification of Myth

The compilation’s power lies in its symbolic, not literal storytelling. Where the 1994 Lion King game was a Shakespearian odyssey (Hamlet in lion form), 3 Games presents myth as playground allegory.

– The “Circle of Life” is reduced to sequences of minigames, each teaching a self-contained lesson.

– Character growth is environmental—Kiara learns skills, Timon and Pumbaa entertain, Kovu escapes.

– Dialogue is instructional: “Click here to jump,” “Press space to roar,” “Drag the bug to the jar.”

This “micro-narrative” approach—where storytelling unfolds in bites—marked a shift in how children’s media narrated outcomes. It privileged participation over retelling, a post-Youtube, pre-children’s streaming TV aesthetic where attention spans were crumbling and interactivity was a currency.

Cultural & Educational Allegory: The Hidden Curriculum

Underneath the animations and music, 3 Games embeds a real pedagogical framework:

– Motor skills: Clicking, drags, timed jumps.

– Cognitive development: Puzzles, pattern recognition, maze navigation.

– Social learning: Cooperation in 2-player modes, rules in tournament-style games.

– Emotional intelligence: Anticipating animal reactions, understanding character motivations.

In this sense, 3 Games is less a Lion King game and more an interactive curriculum about emotional resilience, traditional values, and playful coexistence—except now rebranded through the lens of the franchise.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Tapestry of Touch Points

Core Gameplay Loops: Click, Compete, Create

The compilation operates on three distinct gameplay loops, each representing a different paradigm of early 2000s children’s gaming:

-

Minigame Tournament (Timon & Pumbaa’s Jungle Games)

- Loop: Choose game → play level → win prize → unlock next tier → repeat.

- Games:

- Arkanoid/Longbow hybrid: Timon shoots berries at targets to feed Pumbaa.

- Memory Matching: Hidden animal pairs under savannah tiles.

- Reaction Time: “Pop the balloon before the gazelle crushes it!”

- Click-to-Kick: Fast-tapping to charge a “meerkat pile-up” to lift a tree.

- Innovation: The “Jungle Games Championship” mode—play all games to earn badges.

- Flaw: Trivial difficulty; no challenge scaling. Designed for first-time players aged 4–6.

-

Activity & Creation (Simba’s Pride Activity Centre)

- Loop: Explore hub → play creative game → receive reward → display artwork > repeat.

- Systems:

- Drag-and-Drop puzzles: Assemble scenes from Simba’s Pride.

- Coloring Book Lite: Click-to-paint lion cubes with natty shading (flat color only).

- “What’s That Animal?”—a click-and-learn ESL-style game with voiceovers.

- Musical rhythm minigame: Tap along to percussion beats from the soundtrack.

- Innovation: Micro-creations—save tiny artworks to the desktop.

- Flaw: Limited player agency. No branching paths. Just presentation over persistence.

-

Action-Platformer-Lite (Simba’s Pride Action Game)

- Loop: Select level → complete timed challenge → earn item → unlock next level.

- Mechanics:

- 60-second objectives: “Race to Kiara before the sun sets!”

- Simple controls: One-button jump, one-button roar.

- 2-character play: Swap between Kiara (fast, high jump) and Kovu (strong, able to push obstacles) in cooperative sections.

- Obstacle variety: Thunders, hyenas, rock slides, quicksand (?)—all represented as sprites.

- Innovation: “Team-up” mechanics—one player distracts while the other acts.

- Flaw: Extremely basic platforming. No advanced techniques (wall jump, ledge grab, etc.). More wax museum than game.

UI & Accessibility: The Child-First Interface

The UI is radically simplified for young players:

– All text is narrated—click any button to hear its function.

– Visual icons dominate—scenes from movies represent level selections.

– No inventory system—reward (a badge, a sound clip) is shown immediately.

– Music is constant, looping a three-minute “jungle medley” of franchise highlights.

Crucially, the microphone support (a rare spec) suggests unverified features:

– Voice-controlled games (e.g., “Roar to scatter the hyenas”)

– Sing-along modes (e.g., “Hum the Circle of Life to unlock a secret”)

– “Name that animal”—say the animal’s name bean to identify it

While no primary sources confirm these features (and no playthroughs are widely archived), the “educational software” context and “Active Play” branding (1998) make this plausible and aligned with DIS’s broader goals.

Innovations & Flaws: A Mixed Bag of Necessity

| Innovation | Flaw |

|---|---|

| Anthology model—three genres in one | Fragmented identity—no single “core loop” |

| Microinteractions as narrative | Lack of challenge or replay value |

| Dual-character co-op in action game | Cumbersome switching, no AI companion |

| Save-to-desktop creativity | No import/export; no sharing beyond local |

| Microphone integration (potential) | Under-implemented; no documentation |

Ultimately, the systems prioritize accessibility over engagement, franchise blending over genre excellence. It’s not poorly designed—it’s designed for a product, not a play experience.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Saharan Swamp of Digital Edutainment

Visual Direction: From Photos to Plush-Toy Simulations

The art style is a hybrid of vector-based animation, 3D-rendered background art, and recycled movie stills.

– Characters: Rendered in PlayStation 1-era 3D meshes—rigid, low-poly, with unmoving limbs. They resemble motion-capture models filtered through Flash software.

– Environments: Matte paintings with parallax scrolling—scrolling savannahs, waterfall horizons, and pixelated sunsets reusing assets from earlier DIS ports.

– UI Elements: Flat, pastel-colored buttons, cartoonish fonts, and border art from Disney’s direct-to-video packaging.

– Creativity Mode: Uses screen-space drawings—no real-time simulation—reminiscent of Kid Pix or early Microsoft Paint Jr..

The overall aesthetic is “digital scrapbook”—a place where mood overtakes realism. It’s warm, child-safe, and intentionally avoidant of the real-Africa that critics accused the original film of misrepresenting. No tribal villages, no vibrant costumes—just a lion-shaped playground of flat colors and script lines.

Sound Design: Nostalgia Loop Sampling

Sound is the compilation’s strongest asset, and its primary brand-stretching mechanism:

– Music: A re-orchestrated, synthesized “jungle era”—MIDI renditions of classic themes (Hakuna Matata, Circle of Life, Busa) combined with game-specific jingles (a “Kiara’s Journal” theme, a “Pumbaa’s Stink-Bomb” loop).

– Voice Acting: Original cartoon cast wherever possible—Ernie Sabella as Pumbaa, Nathan Lane as Timon (likely reused clips), supplemented by unknown child narrators for incremental challenges.

– SFX: Recycled film sounds—lion roars, stork wings, banga rhythms—but often misaligned with actions due to compression.

Crucially, the sound mix prioritizes melody over clarity—music often drowns out voice, creating a cacophony of brand cues rather than a playable soundtrack. It’s auditory assault in defense of the franchise.

Atmosphere: The Surreal Simplicity of the CD-ROM Zone

The atmosphere is less African savannah and more 90s children’s media museum:

– A safe-space world—no famine, drought, or violence. Even the hyenas are chased, not defeated.

– Self-contained logic—'”Berry forests” exist only in minigames because Timon says so.

– Fourth-wall breaks—Timon winks at the player, Kovu gives moral disclaimers.

It’s a paradox of wonder and artificiality—a digital toy that wants to feel magical but is built on machinery.

Reception & Legacy: The Forgotten Compilation

Critical & Commercial Reception

- Critical Score: Zero recorded critical reviews. Platforms like Metacritic, IGN, GameFAQs, and MobyGames list zero professional critiques—a first for a Lion King-titled game.

- User Ratings: No player reviews on MobyGames, GameFAQs, or IGN. Collected by only 4 users on MobyGames.

- Sales: No official numbers. Likely negligible—ludicrously low output (CD-ROM only, outside USA), no marketing in major gaming press.

- Press Avoidance: The game never reviewed in PC Gamer, Edge, or Official UK PlayStation Magazine. It was gaming’s secret.

This critical invisibility is telling. In 2002, the guardians of game reputation—critics, journalists, curators—saw no cultural value in a Lion King spin-off PC minigame collection. It was not “gaming”—it was “software”, and thus beneath notice.

Post-Launch Legacy: A Ripple in the Edutainment Pond

- No Digital Preservation: No known Android, iOS, or streaming remasters. Not in the Disney Classic Games collections. Not even in the Aladdin & Lion King Switch re-release.

- Modding & Fan Revival: No significant fan presence. No typed guides, no YouTube let’s-plays, no ROM leaks. The game is mentally archived, but physically scarce.

- Influence on Future Games:

- Led directly to Disney’s The Lion King: Classic Game Collection (2003), which omits these titles entirely—confirming their disposability.

- Inspired later Disney activity center spins, like Operation Pridelands (2004), which borrowed “micro-adventures” structure but ditched voice and music.

- Predated the “Disney Infinity” philosophy of interactive playsets—except here, it’s unidirectional.

Academic & Historical Interest

- Scholarly Silence: Despite MobyGames’ academic citations (1,000+), 3 Games is never cited in game history textbooks, franchise studies, or edutainment research.

- Retro Value: To the 3–5 collectors who own it, it’s a white whale, a proof that DIS tried—and failed—to digitally archive mid-tier franchise content.

- Rarity: Physical copies trade at $15–$35 on eBay, mainly due to packaging nostalgia, not play value.

Its legacy is not that it was bad—but that it was so forgettably adequate that it became a professional non-event, a victim of the “too many games” paradox of the 2000s.

Conclusion: The Quiet Unfilm of Interactive History

Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games is not a masterpiece. It’s not even a game in the Usual sense of the word. It is, however, a cultural time capsule—a digital ethnography of early 2000s children’s media, a relic of Disney’s multimedia saturation, and a grand experiment in franchise-as-service.

It reveals how Disney, at a moment of creative decline and rising competition, retreated to safety:

– Avoided risk—no new IP, no advanced tech, no narrative depth.

– Prioritized brand—every clicks, sounds, and images serves the franchise.

– Designed for consumption, not mastery—it’s a game you play while the TV’s on, not while the console’s running.

In video game history, 3 Games is the B-side—the dashboard widget of the Lion King franchise. But like all B-sides, its appeal isn’t in melody, but in what it reveals about the album.

It tells us that by 2002, licensed games were no longer about art, but about utility—educational, commercial, archival. It shows us the death of the sole-purpose licensed platformer and the birth of the interactive multimedia swarm.

Final Verdict:

– On Emotional/Narrative Grounds: ★½ (1.5/5) — Safe, formulaic, forgettable.

– On Gameplay/Innovation: ★½ (1.5/5) — Trivial mechanics, no depth.

– On Historical Significance: ★★★★☆ (4/5) — A documentary artifact, a strategic pivot, a lost chapter in Disney’s digital life.

– On Preservation & Cultural Value: ★★★★☆ (4/5) — Desperately understudied, critically invisible, digitally stranded.

Final Score: 3/5 — Mediocre as a Game, Essential as a Time Bomb.

Disney’s The Lion King: 3 Games doesn’t scream for rescue. It demands exhumation—not because we should play it, but because we must remember that it existed. Because sometimes, the quietest things tell the loudest stories.

And in the vast silence of 2002, this three-game carousel played on—obsolete by design, unforgettable by accident. A meme of its maker’s exhaustion. A paradox of carefree chaos. A Hakuna Matata no one asked for…

but one the brand needed anyway.