- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Disney Interactive, Inc.

- Developer: Disney Interactive Victoria

- Genre: Educational, Pre-school, toddler

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Coloring, Memory, Mini games, Mouse control, Music, Puzzle

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 84/100

Description

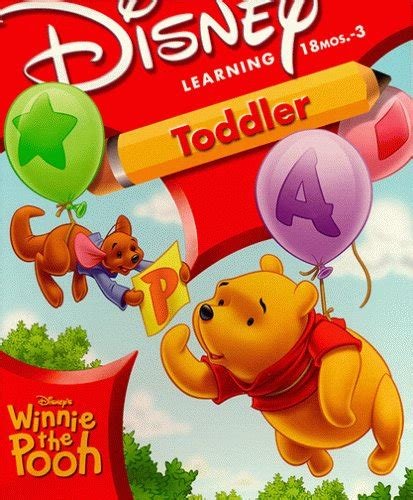

Disney’s Winnie the Pooh: Toddler is an educational computer game set in the Hundred Acre Wood, designed for very young children. It features mouse-controlled mini-games introduced by Pooh, Piglet, Tigger, and Christopher Robin, where toddlers learn letters, shapes, numbers, and opposites through activities like bursting balloons, matching items, and music creation—all without requiring clicks, as interactions occur through simple cursor hovering.

Gameplay Videos

Disney’s Winnie the Pooh: Toddler Free Download

Disney’s Winnie the Pooh: Toddler: Review

Introduction

In the golden age of 1990s edutainment, few franchises held the universal charm of Winnie the Pooh. Released in 1999 by Disney Interactive, Disney’s Winnie the Pooh: Toddler aimed to introduce the youngest players to digital learning through the gentle, honey-padded world of the Hundred Acre Wood. This title stands as a fascinating artifact of early childhood gaming, predating touchscreen ubiquity and designed around a revolutionary no-click mouse interface. Yet, beneath its vibrant watercolor aesthetics lies a product emblematic of its era’s limitations—charming but shallow, innovative yet repetitive. This review dissects Winnie the Pooh: Toddler not merely as a game, but as a cultural and technological milestone, arguing that its legacy lies in its ambitious design philosophy and faithful adaptation of A.A. Milne’s characters, even as its educational depth ultimately confines it to a niche historical footnote.

Development History & Context

Crafted by Disney Interactive Victoria—a studio specializing in licensed children’s titles—the game emerged from a deliberate vision to create lapware, software designed for shared parent-child interaction. The developers, led by designer A. Hope Hickli and senior programmer Matthew Powell, faced the technological constraints of 1999 CD-ROMs: limited storage space, modest graphical fidelity, and the necessity of supporting low-end hardware. Their solution was groundbreaking: an interface requiring no mouse clicks, only hovering. This eliminated the fine motor skills barrier for toddlers, aligning with child development principles of cause-and-effect learning. The gaming landscape of the late ’90s saw Disney leveraging its animation dominance to dominate the edutainment market, competing against franchises like Reader Rabbit and JumpStart. Winnie the Pooh: Toddler arrived alongside Disney’s broader “Learning” series (Preschool, Kindergarten), forming a cohesive educational arc. Its release on Windows and Macintosh, with a later PlayStation port in 2002, reflected Disney’s strategy to saturate multiple platforms with character-driven content, capitalizing on the franchise’s enduring appeal across generations.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Winnie the Pooh: Toddler eschews traditional narrative structure in favor of a sandbox approach. The game opens with Pooh, Piglet, Tigger, and Christopher Robin relaxing under a tree in the Hundred Acre Wood, establishing a theme of communal tranquility. Players select from five activities via hover-activated hotspots, each hosted by a character who introduces a micro-narrative. Piglet’s balloon game, for instance, frames learning as a collaborative rescue: Pooh floats into a tree to retrieve honey, gets stranded by a breeze, and friends join him in a precarious airborne predicament. The narrative resolution—popping balloons to float down—reinforces teamwork without conflict. Similarly, Tigger’s “What Do I Like?” memory game uses character preferences (Pooh’s honey, Roo’s lollipop) as learning devices, while Christopher Robin’s musical segment celebrates self-expression. Dialogue is sparse but intentionally crafted: Laurie Main’s warm narrator guides players with clear, repetitive phrases (“Who likes honey?”), while character voices (Jim Cummings as Pooh/Tigger, Gregg Berger as Eeyore) stay true to their established personas. The overarching theme is gentle discovery, emphasizing curiosity over achievement. However, the absence of a cohesive storyline underscores the game’s identity as a set of isolated activities rather than an immersive world.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The core gameplay loop revolves around mouse hovering, a mechanic that defines both the game’s innovation and its limitations. All actions—launching activities, selecting options, interacting with elements—triggered by cursor proximity, without clicks. This accessibility is bolstered by a forgiving design: no failure states, no time limits, and instant visual/audio feedback. The five mini-games represent distinct learning objectives:

– Print Workshop: A hub for offline creativity, offering 13 coloring pages, name tags, and bookmarks. The wooden desktop interface unrolls options when hovered, with a print function extending play beyond the screen.

– Piglet’s Balloon Game: A cause-and-activity where players pop balloons to reveal shapes, letters, or numbers. Progression escalates difficulty by introducing new characters and items, but lacks deeper engagement beyond labeling.

– Pooh’s Opposites: A hotspot-based exploration in Pooh’s cottage, demonstrating contrasts (e.g., open/closed door, big/small cup). The simplicity here borders on redundancy, with the entire activity completable in minutes.

– Tigger’s “What Do I Like?”: A memory game where players match characters to their preferences after a brief demonstration. Repetition aids recognition, but the cycle restarts identically after each round.

– Christopher Robin’s Music: An interactive jukebox where hovering over characters triggers songs or instrumentals. Kanga sings about shapes, Pooh about sharing, alongside environmental animations (buzzing bees, falling apples).

While the no-click interface is revolutionary for toddlers, the systems are undermined by shallow depth. Activities lack progressive complexity, and the absence of a narrative spine makes sessions feel disjointed. The Print Workshop’s offline extension is a clever nod to parent-child bonding, yet it highlights the game’s core flaw: minimal replayability once initial curiosity fades.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Winnie the Pooh: Toddler excels in transporting players to a meticulously realized Hundred Acre Wood. The world-building leans on Disney’s animation legacy: fixed, flip-screen environments evoke the watercolor textures of classic Pooh shorts, with soft pastels and rounded forms. Character animations are fluid and expressive—Tigger’s bouncing energy, Eeyore’s drooped posture—captured through detailed sprite work by artists like Calvin Jones and Bob Parr. The art direction prioritizes clarity: objects are large and uncluttered, with high-contrast colors ideal for developing vision. Sound design is equally meticulous. Darren McGrath’s score blends gentle orchestral themes with character-specific melodies (e.g., Pooh’s honey-hunting motif). Voice acting is a highlight: Jim Cummings’ dual performance as Pooh and Tigger infuses dialogue with warmth, while Laurie Main’s narration provides a soothing, authoritative guide. Environmental sounds—balloon pops, train whistles, bees buzzing—create a soundscape of ambient discovery. This sensory cohesion makes the world feel alive and inviting, a digital extension of Milne’s idyllic forest that prioritizes comfort over stimulation.

Reception & Legacy

At launch, Winnie the Pooh: Toddler received mixed but generally favorable reviews. FamilyPC Magazine awarded it 84%, praising its “great animation, terrific songs, and adorable cast” but noting it “couldn’t capture the interest of toddlers or their parents,” citing a lack of activity variety and educational depth. Contemporary critics echoed this: Edutaining Kids lauded the graphics but found content “shallow,” while New Straits Times highlighted its karaoke segment as a standout. Commercially, the game benefited from Disney’s marketing muscle, appearing in the “Disney Big Rig” mobile showroom and bundled in “Disney Learning” sets alongside Mickey Mouse titles. Its legacy, however, is nuanced. The no-click interface influenced later toddler games, emphasizing accessibility over complexity. Yet, its reputation has soured with time; modern retrospectives (like Pooh Fandom Wiki) decry its “limited content” and activities that “children and adults alike wonder ‘what’s the point?'” The game remains a cult curiosity among edutainment historians, remembered for its ambitious design but overshadowed by deeper titles like Reader Rabbit. It occupies a transitional space between click-heavy PC games and touch-based mobile apps—a testament to an era’s experiments in digital childhood.

Conclusion

Disney’s Winnie the Pooh: Toddler is a product of its time and a mirror of its contradictions: artistically rich, educationally thin; innovative in interface, conservative in scope. Its greatest achievement is creating a faithful, accessible digital sandbox that honors Pooh’s ethos of gentle exploration. Yet, its shallow activities and lack of replayability prevent it from transcending its niche. As a historical artifact, it stands as a bold, if flawed, attempt to redefine early childhood interaction—one that prioritized inclusivity over engagement. For modern parents or educators, it offers little practical value, but for gaming historians, it remains a fascinating study in 1990s edutainment design. Ultimately, Winnie the Pooh: Toddler is less a game and more a digital lullaby: comforting, charming, and best experienced in short, sweet doses before drifting toward more substantive dreams.