- Release Year: 1980

- Platforms: Antstream, Atari 2600, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Atari, Inc., Atari Interactive, Inc., Microsoft Corporation

- Developer: Atari, Inc.

- Genre: Action, Driving, Racing

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Dot collection, Lane switching, Speed control

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

Dodge ‘Em is an action-racing game on the Atari 2600 where players control a car on a four-lane track divided into quadrants, aiming to collect all dots to earn points and advance levels while avoiding a rival car that moves in the opposite direction and attempts to cause collisions. The gameplay involves switching lanes at track breaks and adjusting speed, with a two-player mode allowing one player to collect dots and the other to control the crash car for competitive fun.

Gameplay Videos

Dodge ‘Em Free Download

Atari 2600

Dodge ‘Em Reviews & Reception

honestgamers.com : Masochistic, but nice.

atarihq.com (80/100): Dodge ‘Em is typical of an early Atari 2600 game. It’s simple, has a great two-player mode, and it’s remarkably fun to play.

Dodge ‘Em: A Definitive Analysis of Atari’s Overlooked Maze Racer

Introduction: The Shadow of Pac-Man and the Ghost of Head-On

In the crowded pantheon of Atari 2600 titles, few games occupy as curious a niche as Dodge ‘Em. Released in September 1980, it arrived at the zenith of the console’s popularity and the genre’s explosion, directly in the long shadow of Pac-Man while standing on the shoulders of Sega’s 1979 arcade hit, Head-On. Often dismissed as a mere clone or a footnote to greater maze games, Dodge ‘Em is a study in minimalist design, deceptive challenge, andinnovative multiplayer构架. Its legacy is one of quiet influence and misunderstood depth. This review argues that Dodge ‘Em is not merely a competent adaptation of an arcade concept, but a distinct and cunningly difficult experience that pioneered asymmetrical multiplayer on the console, suffered from significant design limitations, and ultimately represents a critical, if flawed, link in the evolutionary chain of the competitive maze genre. To understand Dodge ‘Em is to understand a pivotal moment where arcade design principles were translated—and sometimes lost—in the crucible of the home console.

Development History & Context: From Gremlin’s Garage to Atari’s Trailer

The Arcade Provenance: Sega/Gremlin’s Head-On

To discuss Dodge ‘Em is to first acknowledge its source. The game is a direct, unlicensed adaptation of Sega/Gremlin’s 1979 arcade game Head-On. Developed by Lane Hauck and Bill Blewett at Gremlin Industries (acquired by Sega in 1978), Head-On was a commercial success, ranking among the top 10 arcade games of 1979. Its core concept—a single-screen maze of concentric lanes, dots to collect, and relentless computer-controlled opponent cars—was revolutionary. Crucially, Hauck’s shift from a two-player Head-On where both humans tried to ram each other (leading to quick, unrewarding matches) to a single-player game against AI, with the goal of dot collection, saved the concept and established the foundational loop that Dodge ‘Em would replicate.

Carla Meninsky and the Atari 2600 Conversion

Dodge ‘Em was the first project for Atari programmer Carla Meninsky, hired in 1979. Assigned a list of concepts including a “car crash maze game,” she chose Head-On. Working within the extreme technical constraints of the Atari 2600—4 KB of ROM, minimal memory, and a temperamental TIA chip—Meninsky’s task was to compress an arcade experience into a home environment. Her achievement was a remarkably faithful translation. The concentric roadways, lane-changing gaps, dot collection, and the core tension of a single opposing car (later two) were all preserved. The Atari Archive notes she even “cheated an extra computer cycle” to optimize performance, a testament to her skill.

Technological Constraints and Design Trade-offs

The 2600’s hardware dictated a minimalist aesthetic. As TV Tropes categorizes it, the game is Minimalism personified: a maze, cars, dots, a score. There is no flicker to depict two enemy cars simultaneously on higher screens; instead, the infamous “flicker” technique merges their sprites across frames, a practical but visually jarring solution. The fixed, flip-screen perspective (no scrolling) and the single-color car sprites (orange for player, blue for enemies) were hardware-driven necessities. The sound, however, was a relative high point: contemporaneous reviews like Woodgrain Wonderland’s praised the “sounds of engines revving and tires squealing,” a clever use of the TIA’s limited channels to provide crucial audio feedback.

The Gaming Landscape of 1980

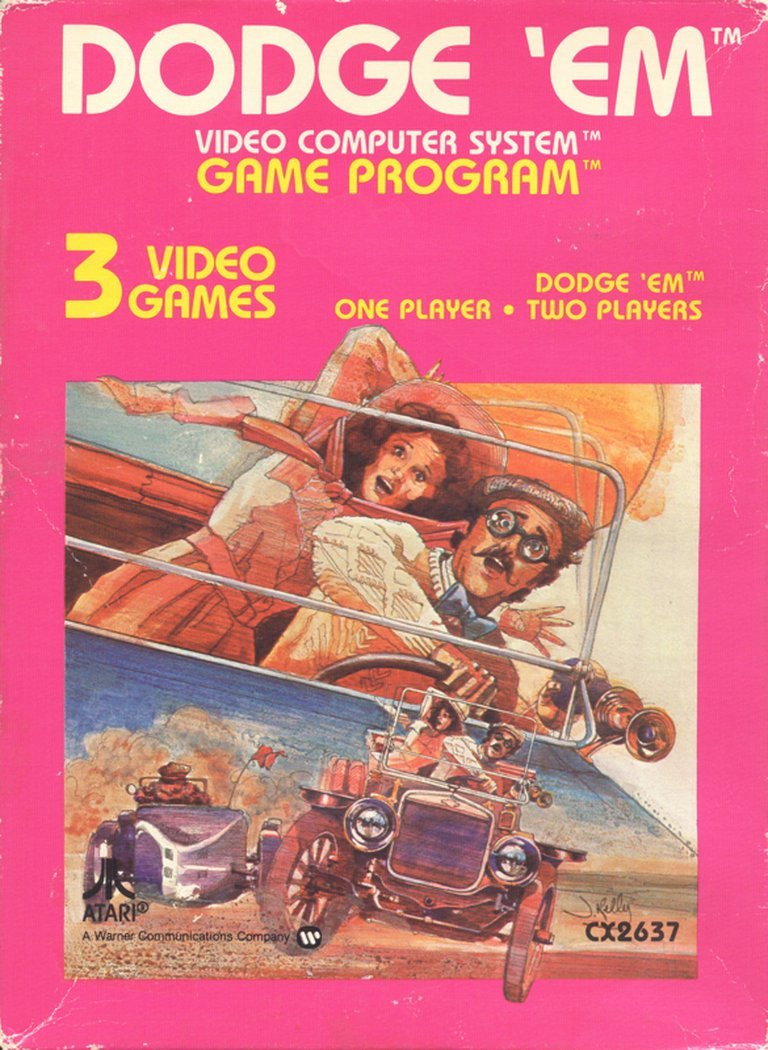

Dodge ‘Em entered a market obsessed with maze games. Pac-Man had dominated arcades in 1980 and was approaching home consoles. Atari’s own library included Maze Craze and Haunted House. The game’s release as Dodger Cars by Sears for the “Sears Video Arcade” (a re-badged 2600) highlights the era’s retail partnerships. It existed in a crowded field but offered a unique, purely defensive twist: you could not attack your pursuers. This “deadly dodging” premise, where the AI could ram you with impunity but you could not reciprocate, set it apart from both Pac-Man (power pellets) and Head-On (where collision was mutual).

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Aesthetics of Absence

Dodge ‘Em presents perhaps the purest case of No Plot? No Problem! in the early Atari library. There is no narrative, no backstory for the driver, no explanation for the dots or the malicious opposing car. The manual, as cited on AtariAge, provides no lore; it simply states the rules. This is not a failing but a thematic core. The game is an abstract test of spatial awareness, pattern prediction, and endurance.

Thematic Interpretation: The Sisyphean Racer

The game can be interpreted as a metaphor for futility and relentless pressure. The player’s car is forever counter-clockwise, a predetermined path with no braking (Dodge by Braking is Defied). The dots represent a monotonous, repetitive task—clearing a screen—constantly undermined by the ever-present threat of the blue car(s). The game’s structure reinforces this: you lose one life for every five screens cleared, but dying resets the entire maze, forcing you to recollect all dots. This Continuing Is Painful mechanic turns progress into a fragile thing, making each life a Sisyphean effort. The Kill Screen at 1080 points (due to a score rollover bug where 1000 reads as “00”) is not an endpoint of victory but a technical barrier—the game crashes, offering no closure, only the recognition of a systemic limit.

The Philosophy of Minimalism

The game’s starkness is its statement. The concentric lanes are a geometric prison. The “gaps” in the road, which TV Tropes notes are Red Herrings for Pac-Man-style teleportation, are merely lane-changing tools—a reminder that movement is strictly controlled. The color-coding (orange vs. blue) is pure Color-Coded for Your Convenience, stripping away any pretense of individuality or story. The player is an orange dot-collector in a blue threat-world. This minimalism forces focus entirely onto the mechanics and the player’s twitch reactions and planning.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Calculus of Collision

Core Loop and Lane Logic

The fundamental loop is straightforward: drive counter-clockwise around one of four concentric lanes, collect all dots (pellets), advance to the next screen. The constraint is that you can only change lanes at the four cardinal gaps (top, bottom, left, right) between quadrants. This creates a grid-like decision space. Your sole offensive tool is the “turbo” button, which doubles your car’s speed.

The AI: Predictable and Ruthless

The computer-controlled car(s) exhibit a fascinating, Artificial Stupidity that is actually a clever design choice. Its rules are simple:

1. If on the same lane as the player, it stays there.

2. If on a different lane, it moves one lane closer to the player’s lane at the next available gap.

3. It never uses turbo and cannot change more than one lane at a time.

This predictability is both a curse and a blessing. As TV Tropes notes, “the cramped maze actually makes this a disadvantage at first.” On early screens with one car, a skilled player can exploit this to always stay one lane ahead. However, the introduction of a second car on screens 3-5 shatters this calculus. With two blue cars adhering to the same simple rule, Deadly Dodging is Defied—the player cannot trick the AI cars into crashing into each other. The challenge shifts from exploiting AI to managing pure, chaotic evasion.

The Turbo Button: Awesome, but Impractical

The turbo is the player’s only asymmetry. Doubling speed allows you to beat an enemy car to a gap. However, it has severe drawbacks: you can only change one lane while turboing (vs. two at normal speed), and the increased speed makes last-minute lane corrections more likely to cause a collision. Using turbo recklessly will bottleneck you directly into an oncoming car. It is a tool for precise, calculated bursts, not a panic button.

Difficulty and Progression

The Difficulty by Acceleration switch on the Atari 2600 controller increases the enemy cars’ base speed and alters their starting positions (fixed vs. random). Progression is defined by screens: 1-2 have one car, 3-5 have two cars. Completing screen 5 and surviving advances you back to screen 1, but subtracts a life (“losing one turn” per the Wikipedia entry). With three initial lives, the theoretical maximum progression is 15 screens (3 lives * 5 screens per life cycle), culminating in the Kill Screen at 1080 points.

Multiplayer Innovation

This is where Dodge ‘Em transcends its modest presentation. It includes three distinct modes:

1. Alternating Turns (Mode 2): Classic hot-seat. Players alternate as the dot-collector after each crash.

2. Simultaneous Asymmetrical Roles (Mode 3): A revolutionary design for 1980. One player controls the orange car (score); the other controls a blue crash car. If the blue car hits orange, the players switch roles. This creates a dynamic, psychological contest of sabotage and survival, directly foreshadowing later games like Pac-Man Vs. (2005). As Atari HQ’s review enthuses, the “third game mode is an absolute riot.”

3. Co-op/Competitive Hybrid (Implied): The simultaneous mode inherently creates a competitive high-score chase where both players are both attacker and defender across the session.

Flaws and Frustrations

Dodge ‘Em is beset by design choices that feel punitive by modern standards. The Continuing Is Painful reset of the entire maze on death is brutal. The Cut and Paste Environments—five screens differing only in color palette—can induce monotony. The lack of any defensive maneuver against the AI’s “Car Fu” (My Rules Are Not Your Rules) can feel unfair. And the kill screen provides no victory, just a crash.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Architecture of Anxiety

Visual Design and Atmosphere

The game’s world is a top-down, fixed-screen arena of four square, concentric lanes. The aesthetic is pure functionalism. The “road” is often a solid color block (black, blue, etc.) with a thin border. The dots are small, square pellets. The cars are blocky, low-resolution sprites. There is no sense of scale, speed, or environment—only the abstract relations between shapes. The “atmosphere” is one of tension created solely through movement and imminent collision. The color shift between screens (as noted in the Wikipedia and MobyGames descriptions) is the only visual variation, providing a subtle cue of progression but no true world-building.

Sound Design: A Triumph of Ingenuity

On the limited TIA chip, Meninsky created sound that is iconic and informative. The “engine” sound is a continuous low hum that changes pitch when turbo is engaged (a rising whine), immediately communicating your speed state. The “tire squeal” or crash sound—a sharp, percussive noise—is the most important audio cue, signaling instant failure. Reviews consistently praised this aspect. It is not melodic but purely diegetic and functional, heightening the visceral impact of every near-miss and crash.

Reception & Legacy: The Quietly Influential Also-Ran

Contemporary Reception

Dodge ‘Em received generally positive but not spectacular reviews. Video magazine’s “Arcade Alley” column called it “one of those rare videogames that is exciting in either one- or two-player versions,” though it noted the early stages could become “predictable.” It earned an Honorable Mention for “Best Solitaire Game” at the 1982 Arkie Awards. Scores from retrospective critics range from 40% (HonestGamers, finding it “blah” with “glaring issues”) to 83% (Woodgrain Wonderland). The consensus, reflected in its 71% average on MobyGames and #113 ranking on the Atari 2600, is that it is a solid, above-average early title but not a classic on the level of Ms. Pac-Man or Mouse Trap.

Commercial Performance and Rarity

Sales data is scarce. The Atari Archive cites that in the latter half of the 1980s, it sold only 2,572 copies—a paltry figure for a VCS title even in its twilight. This suggests it was not a major hit, though the aftermarket prevalence (as noted by MobyGames’ “Collected By” stats) implies initial shipments may have been decent, and its low price kept it in circulation. Its Sears rebranding (Dodger Cars) expanded its reach.

Influence and the Head-On Family Tree

Dodge ‘Em‘s true legacy is as a key node in the Head-On family tree, which had vast influence:

* Direct Successors: Sega’s Head-On 2 (1979) and later Car Hunt (arcade) and Pacar (SG-1000) evolved the formula with more complex mazes, power-ups, and lane reversal.

* The Namco Connection: The Atari Archive highlights the tantalizing, unproven link between Head-On and Pac-Man. Gremlin founder Frank Fogleman hosted Namco’s Masaya Nakamura in 1978, who reportedly played Head-On all night. Pac-Man‘s 1980 release shares the maze-and-dots core, suggesting conceptual cross-pollination.

* The Bally BASIC Clones: On the Bally Professional Arcade, Collision Course (Mike Peace) and Smash Up (part of Quadra by Mike White) were more sophisticated home computer interpretations, adding fuel gauges and better graphics, showing the desire for a “fuller” version of the concept.

* The Regulatory Quirk: The blog’s deep cut on Sega’s Dottori-kun—a stripped-down Head-On bundled in Japanese cabinets to meet regulations—and its hack Dottori-Man Junior (a Pac-Man variant using Head-On rules) shows the concept’s bizarre, enduring life in industry infrastructure.

* Genre Evolution: The core “collect dots while pursued in a confined arena” mechanic is a direct ancestor to later titles like Rally-X (Namco, 1980), which added patrol cars and flags, and even modern .io games like Dodge.

Conclusion: A Flawed Pioneer Deserving of Reassessment

Dodge ‘Em is not a great game by any absolute measure. Its graphics are primitive even for 1980, its worlds repetitive, its single-player campaign short and brutally difficult, and its core loop lacks the strategic depth or power fantasy of its contemporaries. The kill screen is a cold, unceremonious end. Yet, to dismiss it is to overlook its significant, if niche, contributions.

It is a pioneer of asymmetrical multiplayer on a home console, offering a role-switch mechanic decades before it became a trend. It is a masterclass in tension through constraint, where the lack of offensive options forces a pure, defensive mindset. It is a faithful and clever translation of an arcade hit under severe hardware limitations. And it is a fascinating historical document, capturing a specific moment where the “maze game” formula was being experimentally tweaked away from the Pac-Man template toward pure evasion and spatial puzzle-solving.

Its MobyScore of 6.6/10 and its “blah but with cool bits” assessment from critics like HonestGamers are fair. But fairness also demands recognition of its innovative spirit. Dodge ‘Em is the game you put in when you want a quick, intense, mentally draining duel with a friend. It is the game whose AI patterns you memorize only to have them rendered obsolete by the second car. It is the game whose turquoise kill screen is a badge of honor for those who reach it.

In the final tally, Dodge ‘Em belongs not in the pantheon of the 2600’s immortals, but in a special category of influential curios—a game whose specific DNA can be traced through the genre’s family tree, whose design ideas were ahead of their time in multiplayer, and whose brutally honest minimalism remains a compelling, if punishing, test of skill. It is a testament to Carla Meninsky’s talent that she could wring such a tense, strategic, and socially engaging experience from such a sparse canvas. For that, Dodge ‘Em earns its place not as a classic, but as a critical, unforgettable artifact of game design history.