- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: PLAY-publishing.com

- Developer: PLAY-publishing.com

- Genre: Simulation

- Gameplay: Arcade, Mini-games

Description

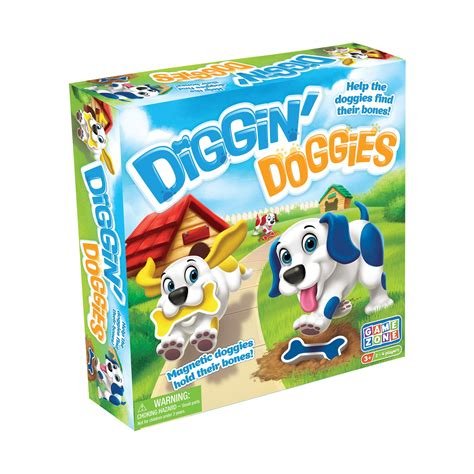

Doggies is a simulation game developed and published by PLAY-publishing.com for Windows in 2010. Set within an arcade-themed environment, the game focuses on a variety of mini-games, providing a casual and interactive experience centered around playful simulations.

Doggies: A Review

Introduction: The Phantom of the Simulation Niche

In the vast, overcrowded archives of video game history, certain titles exist as spectral presences—known, documented, yet fundamentally elusive. Doggies (2010) is one such phantom. Developed and published by the enigmatic Polish outfit PLAY-publishing.com, this Windows-exclusive simulation title represents a curious Zeitgeist of its era: the early-2010s proliferation of low-budget, digitally distributed “casual” and “life sim” games that sought to capture a fraction of the Nintendogs or The Sims magic with a fraction of the resources. To engage with Doggies is not to engage with a polished product, but with a concept, a repository of intentions, and a stark lesson in the volatility of digital preservation. This review will argue that Doggies is historically significant not for its execution, but for its perfect encapsulation of a specific, now largely vanished, stratum of the PC gaming ecosystem—the budget “shovelware” simulation title sold via fledgling digital storefronts, whose legacy is measured in fragmented data points and the quiet absence of player memory.

Development History & Context: A Blip in the Polish Indie Wave

The Studio and the Vision

PLAY-publishing.com, the sole credited developer and publisher, remains an obscure entity. No credits beyond the studio name are listed on MobyGames, and web archives of their official site (the source of the game’s ad blurb) paint a picture of a small, likely one- or two-person operation. Their catalog, glimpsed through scattered listings, consisted of similarly niche simulation and arcade titles (Mazlíčci, a Czech/Slovak title meaning “Puppies,” which incorporated Doggies in a 2014 compilation). The vision, as stated in the official description, was pedagogical and affective: “funny and informative entertainment… things you’ll learn from the game can be helpfull when taking care of a real dog.” This positioned Doggies not as a pure escapist fantasy but as a quasi-serious “simulator” with a veneer of educational utility—a common marketing tack for pet-care games targeting children or casual adults.

Technological and Market Context

Doggies materialized in a pivotal transitional period, 2010. The landscape was defined by:

1. The Death of Retail Shovelware: The traditional budget-box market for PC games at big-box retailers was collapsing. The rise of Steam (still curating its identity beyond Half-Life 2), GamersGate, and other early digital distributors created a new, low-barrier-to-entry marketplace. This democratization was a double-edged sword: it empowered indie creators but also flooded the space with hastily produced, low-effort titles.

2. The Casual Boom & Mobile Threat: The Wii’s motion-control craze was peaking, and Facebook games like FarmVille were demonstrating the massive audience for asynchronous, simple simulation. Simultaneously, the App Store (launched 2008) was proving that even simpler, cheaper, and more accessible games could dominate playtime. Doggies, a $1.99 Windows game with “beautiful graphics” (by 2010 casual standards), was a direct response to this environment—a PC answer to the touch-screen pet sim, but arriving as the world’s attention was already shifting to phones.

3. Technical Constraints: The system requirements (Windows XP/Vista, 512MB RAM, 128MB DirectX 9.0c card) confirm it was built for mainstream, even aging, PCs. The promise of “beautiful graphics” and “funny animated tricks” suggests simple 2D sprites or very low-poly 3D, likely using a basic game engine like GameMaker or a custom framework. “Infinite gameplay” is a notorious buzzword for such titles, implying lack of a narrative arc or substantive content, replaced by endless repetition of care routines and mini-games.

4. Regional Quirks: Its release in Poland and apparent reliance on a small, regional publisher speaks to a strategy of serving local, overlooked markets before attempting broader international digital distribution. Its inclusion in the 2014 compilation Mazlíčci suggests a degree of regional success or leftover inventory bundling.

Doggies was, therefore, a product of its exact moment: a budget simulation for a transitional PC market, attempting to parlay a simple, universally appealing premise (caring for a dog) into a commercial product in an ecosystem rapidly being reshaped by cheaper, more portable rivals.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Aesthetics of Absence

To analyze the narrative of Doggies is to analyze a void. The official description provides no plot, no characters beyond “you” and “your dog,” and no conflict. There is no storybook ending (contrary to a mistaken Reddit recall of a dog’s death), no dramatic arc, no antagonists. The “theme” is pure, unadulterated domestic routine.

This absence is, in itself, profoundly telling. Doggies represents the utter decoupling of “game” from “narrative” at the lowest stratum of the market. While 2010 was the same year that saw the release of Mass Effect 2, Red Dead Redemption, and Heavy Rain—titles championing complex, cinematic storytelling—Doggies hewed to a pre-1990s conception of gameplay as abstract activity. Its “narrative” is the player’s self-authored story of responsibility and companionship. The dog is not a character but a reactive state-machine: a set of meters (hunger, happiness, cleanliness, perhaps) that fluctuate based on player input. The “theme” is the simulation of care, stripped of any dramatic stakes. It is the video game equivalent of a coloring book: a structured, empty canvas for the player’s imagination, or more accurately, a Skinner box for nurturing instincts. Its thematic depth is zero, and that zero is its defining characteristic, marking it as a relic of a design philosophy that had already been largely eclipsed even in mainstream gaming.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Loop of Maintenance

Deconstructing Doggies requires reading between the lines of its sparse marketing.

Core Gameplay Loop: The cycle is predictably closed: Check Meters → Perform Action (Feed/Walk/Play/Pet) → See Meter Response → Repeat. This is the foundational loop of the virtual pet genre, from Tamagotchi to Nintendogs. The innovation, if any, was the promise of 18 distinct breeds with “varying looks, character and predisposes.” This suggests a layer of statistical differentiation: a Saint Bernard might have higher “stamina” but lower “agility,” affecting mini-game performance. However, without code or deep player accounts, we must assume this differentiation was superficial—likely just aesthetic swaps and minor stat tweaks, not profound behavioral AI.

Mini-games and Competitions: The phrase “start in many competitions to test your pet’s abilities” points to a secondary loop. These were likely simple arcade-style challenges: a fetch mini-game (timed button presses), an obstacle course (rhythm-based or direction inputs), a obedience trial (quick-time events). Their purpose was to provide “infinite gameplay”—a treadmill to grind for “skill points” or currency to buy toys/food, thereby extending the primary care loop with a thin layer of progression. They were the “game” part of the simulator, offering a break from maintenance with discrete, winnable tasks.

Progression & Systems: The description mentions no overarching progression for the player. The dog likely grew from a puppy to an adult, but this was probably a cosmetic and stat-based change over a fixed in-game time, not a narrative journey. “Infinite gameplay” is the key euphemism: there is no end state. The game technically “ends” only when the player abandons it or the dog’s neglect leads to a “game over” (likely a reset). This creates a paradoxical experience: a game with no win condition, only the ongoing management of entropy. It is a digital chore scheduler with positive feedback.

UI and Innovation: Nothing is known of the UI, but one can safely assume a large, colorful, child-friendly interface with prominent icons for actions and clear, pictorial representations of status meters. Its only potential innovation was the bundling of “simulation” (care) with “arcade” (competitions) into a single package, a formula later perfected by games like Dogz or Catz but here presented in a more modest, less customizable form.

The systems are fundamentally flawed by design for any player seeking depth. They are transparent, repetitive, and lack the emergent complexity of even a basic The Sims want system. They succeed, if at all, as a low-stress, repetitive activity for very young children or as mindless background engagement—a “game” to half-play while doing something else.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Architecture of the Generic

With no screenshots extant in the provided sources and the game absent from modern storefronts, the game’s aesthetic must be inferred from its descriptors and context.

Setting & Atmosphere: The world is a minimalist diorama. The mention of walking “to the park or on the beach” suggests a small set of static, pre-rendered or simple 3D environments. There is no open world, no NPCs (other than the dog), no sense of a living place. The atmosphere is one of sterile, placid domesticity. It is the emotional equivalent of a pastel-colored screensaver.

Visual Direction: “Beautiful graphics” was a common, largely meaningless claim in early-2010s digital storefront blurbs. For a $1.99 Polish title, “beautiful” almost certainly meant “smoothly animated, brightly colored, and competently drawn.” The art style was likely generic “cutesy” realism—think slightly less detailed than Nintendogs but aiming for a similar aesthetic of appealing, exaggerated puppy eyes and soft textures. The 18 breeds would have been implemented through palette-swaps and minor model variations on a base dog skeleton.

Sound Design: The only sonic clue is “funny animated tricks,” implying a library of cartoonish yips, barks, and playful sound effects. Music, if present, would have been a single, looped, inoffensive acoustic guitar or ukulele track, designed to fade into the background. The sound design’s goal was to be non-intrusive and emotionally positive—to reinforce the soothing, un-challenging loop.

These elements collectively constructed an experience designed to be inoffensive, accessible, and visually/aurally undemanding. It was a game meant to lower blood pressure, not raise heart rates. Its world was not one to explore, but a pleasant backdrop for the simple, repetitive act of nurturing a digital pet.

Reception & Legacy: The Mathematics of Obscurity

Critical and Commercial Reception at Launch:

Doggies fell into the vast, uncounted majority of games that exist outside the critical radar. No professional critic reviews appear on MobyGames, OpenCritic, or Metacritic. Its GamersGate user score sits at a desolate 2.00 based on two ratings—a tiny sample size that likely represents the polar extremes of “my child likes this” and “this is garbage.” Its “Moby Score” is listed as “n/a,” the database’s way of saying “no one has ever formally reviewed or rated this.”

Commercially, its price point ($1.99) and platform (PC) suggest it sold in tiny, uncounted dribbles. It was not a Steam headline, not an Xbox Live Arcade title, not a mobile hit. It was a quiet offering on the lower shelves of digital distribution, purchased perhaps by a handful of parents looking for a cheap “dog game” for a child, or by the morbidly curious browsing the deep categories of GamersGate. Its sales figures are, for all intents and purposes, zero in the industry’s collective memory.

Evolution of Reputation and Historical Footprint:

The game’s reputation has not evolved; it has atrophied. It is the definition of a “forgotten” title. Searches yield only its metadata, the ad blurb, and the occasional query on forums like Reddit’s r/tipofmyjoystick, where a user in 2021 tried (and failed) to identify it, misremembering details like a female caretaker in a pink shirt (not mentioned in sources) and a dramatic dog death (absent from the actual description).

Its legacy is purely archival. It is a data point demonstrating:

1. The volume of niche, regional, low-budget simulation games that flooded the early-2010s PC digital space.

2. The specific marketing language (“infinite gameplay,” “beautiful graphics,” “informative”) used to sell these titles.

3. The fragility of digital preservation for non-mainstream, low-sales games. Doggies is an “abandonware” candidate in the strictest sense—a title so commercially insignificant its digital storefront presence has likely vanished, its physical copies (if any existed) are scarce, and its own developer/publisher website is a ghost archive.

Influence on the Industry:

Doggies had zero discernible influence on subsequent game design. It did not pioneer a mechanic, define a genre, or build a franchise. Its influence is negative and epidemiological: it is an example of the chaff that made it difficult for genuine, thoughtful indie simulations to gain traction in that era. It represents the “shovelware” problem that platforms like Steam would later combat with curated algorithms and community reviews. In a macro sense, its obscurity is proof of the market’s brutal natural selection. The audience’s time and money flowed toward Nintendogs (on a dominant handheld), The Sims expansions, and eventually, more polished mobile pet games. Doggies was a redundant spec in the data stream, filtered out by the sheer noise of a crowded, transitioning marketplace.

Conclusion: A Scholar’s Footnote

To call Doggies a “bad game” is to engage it on terms it never aspired to meet. It is not a failed artistic statement like E.T.; it is a non-statement. It is a pure commodity, an algorithmic assembly of popular themes (dogs, simulation, mini-games) dropped into a template and released into a digital marketplace with the faint hope of capturing a sliver of consumer surplus.

Its place in video game history is therefore not as a title to be played or celebrated, but as a perfect specimen for study. It is the Rosetta Stone for understanding the layer of the 2010 PC gaming landscape that existed beneath the headlines of StarCraft II and Mass Effect 3. It reveals the machinery of casual game production in a regional context, the hollow promises of “infinite gameplay,” and the ephemeral nature of digital distribution for non-events.

In the final ledger, Doggies earns a historical rating that transcends numerical scores. It is an F for cultural impact, a D- for technical ambition, and an A for representational accuracy of a vast, forgotten stratum of our medium. It is not a game lost to time; it is a game that time never noticed. Its significance lies in its quiet, total erasure—a reminder that for every Minecraft that emerges from indie obscurity, a million Doggies vanish without a trace, leaving behind only a MobyGames entry and the faint, digital scent of forgotten kibble.

Final Verdict: Historically illuminating, experientially null. A ghost in the machine, and a testament to the fact that most games are not made to be remembered, but to be sold.