- Release Year: 1983

- Platforms: 3DO, Android, Arcade, Blu-ray Disc Player, Browser, CD-i, DOS, DVD Player, HD DVD Player, iPad, iPhone, Jaguar, Linux, Macintosh, Nintendo DS, Nintendo DSi, PlayStation 3, PlayStation Now, PSP, SEGA CD, Windows Apps, Windows, Xbox 360, ZX81

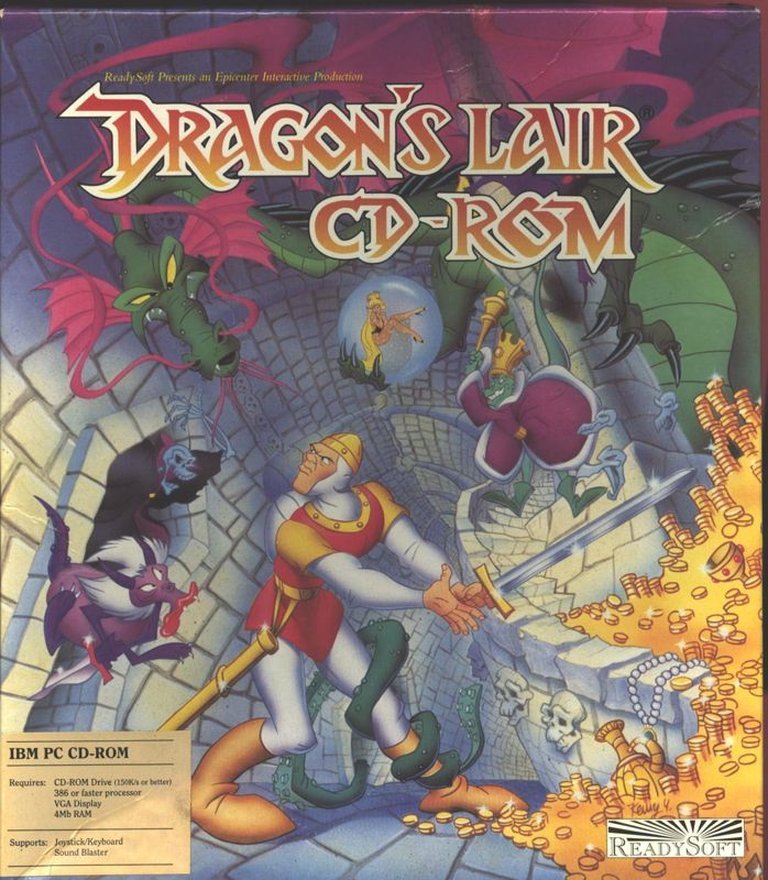

- Publisher: 1C Company, Cinematronics, Inc., Destineer, Digital Leisure Inc., Dragon’s Lair LLC, Electronic Arts, Inc., Elite Systems Ltd., LG Electronics Inc., Microsoft Corporation, Philips Interactive Media, Inc., ReadySoft Incorporated, SEGA Enterprises Ltd., T&E Soft, Inc.

- Developer: Advanced Microcomputer Systems

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Quick Time Events, Timed input

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 62/100

- Adult Content: Yes

Description

Dragon’s Lair is an interactive cartoon movie that debuted in arcades in 1983, featuring the heroic knight Dirk the Daring on his perilous quest through a treacherous dungeon to rescue the beautiful Princess Daphne from the fearsome dragon Singe. Created by legendary Disney animator Don Bluth, the game revolutionized the industry with its groundbreaking Full Motion Video (FMV) technology, presenting players with beautifully animated sequences that require precise button presses and directional inputs at critical moments to progress. As one of the earliest examples of Quick Time Events (QTEs), Dragon’s Lair challenges players to time their actions perfectly to navigate deadly traps, avoid monsters, and ultimately face the dragon in this classic fantasy adventure that has been ported to numerous platforms over the decades.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Dragon’s Lair

PC

Dragon’s Lair Free Download

Dragon’s Lair Patches & Updates

Dragon’s Lair Mods

Dragon’s Lair Guides & Walkthroughs

Dragon’s Lair Cheats & Codes

Nintendo (NES)

Enter codes at the main menu or using Game Genie device.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| BATS | 30 Lives |

| AAXITVNY | Infinite Lives |

| NNXSGSUY | Start With 1 Extra Life |

| KNXSGSUN | Start With 6 Extra Lives |

| NNXSGSUN | Start With 9 Extra Lives |

| PEUIGIAA | Start With Axe |

| ZEUIGIAA | Start With Fireball |

| PANSZIAA | Start On Level 2 |

| ZANSZIAA | Start On Level 3 |

| LANSZIAA | Start On Level 4 |

| IAVNPYAP | Less Energy Gained On Pick-Up |

| YZVNPYAP | More Energy Gained On Pick-Up |

| AEXSGEKY | Protection! |

| SXKYUOVK | Infinite Candle Energy |

| SXVYXOVK | Infinite Candle Energy |

| SUSETNVS | Infinite Health |

| 070C:01 | Sky Walk/Jump + Walk Through Walls/Objects + Never Run Death Routine |

| ATNSZAAZ+GZEGITEI | Invincible |

| 03AF:00 | No Enemies |

| 039C:00 | No Bounce Back |

| 0330:1F | Infinite Health |

| 05EE:F9 | Infinite Lives (Ignore HUD) |

| 05EA:FF | Infinite Gold (Hundred’s Digit) |

| 05EB:FF | Infinite Gold (Ten’s Digit) |

| 05EC:FF | Infinite Gold (One’s Digit) |

| SZUYGNSE | Disable Knife Blocks |

| 0005 A6FB | Infinite Lives (Pro Action Replay) |

| 0003 3527 | Unlimited Energy (Pro Action Replay) |

| 0003 3427 | Unlimited Candle Power (Pro Action Replay) |

Super NES

Enter passwords at password screen or use Game Genie device.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 2D, 4C, 6A, 8B | After the two Snake Bosses |

| 1B, 2D, 7A, 8C | After the large Bat |

| 3D, 4B, 5C, 6A | After the Grim Reaper |

| 1A, 3B, 5C, 6D | The Dragon’s Lair |

| 1-C, 2-D, 3-B, 8-A | Password for all levels |

| 3C62-D70F | Start with Unlimited Lives (Game Genie) |

| D689-0404 | Start with 9 Lives (Game Genie) |

| 3C8C-0FA4 | Protection From Most Hazards (Game Genie) |

| 5D89-6D04 | Slower Timer (Game Genie) |

| 4A84-64D4 | Stop Timer (Game Genie) |

| DF86-0DD4 | Start With the Dagger (Game Genie) |

| D486-0DD4 | Start With the Shuriken (Game Genie) |

| DF88-0F64 | Coins Give 10 (Game Genie) |

PC

Enter codes during gameplay or at main menu.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| GAME | Load the game typing GAME; when the bridge’s monster gets you (first screen), press ESC and you’ll see the final sequence |

| [Esc] + R + / + L + N + 7 and press Fire | View FMV sequences |

| [Esc] | Last scene |

| YTRY | Bonus (easy) – DVD |

| CHIP | Bonus (hard) – DVD |

| MAGE | Mordroc (easy) – DVD |

| DARK | Mordroc (hard) – DVD |

Dragon’s Lair: Review

Introduction

In the annals of video game history, few titles have captured the imagination and sparked such intense debate as Dragon’s Lair. Released in arcades during the summer of 1983, this interactive LaserDisc masterpiece wasn’t merely a game—it was a cultural phenomenon. When players crowded around its cabinet, transfixed by fluid, Disney-quality animation and cinematic storytelling, it represented a quantum leap beyond the blocky sprites and repetitive loops of its contemporaries. Yet, beneath its revolutionary veneer lay a contentious core: was it a groundbreaking evolution of interactive media, or a glorified tech demo masquerading as a game? This exhaustive analysis argues that Dragon’s Lair remains an indispensable artifact of gaming’s evolution. Its legacy, defined by audacious ambition and technological spectacle, transcends its flawed gameplay to cement its status as a pivotal, if paradoxical, masterpiece that redefined the medium’s possibilities.

Development History & Context

Dragon’s Lair emerged from a confluence of visionary ambition and technological necessity. Its genesis lies with Rick Dyer, president of Advanced Microcomputer Systems (AMS), who had long pursued his “Fantasy Machine”—a concept blending text adventures with early multimedia. Dyer, inspired by Sega’s LaserDisc title Astron Belt (1982) and Don Bluth’s animated feature The Secret of NIMH (1982), envisioned an interactive film where player choices dictated narrative progression. To realize this, he partnered with Bluth, a former Disney animator who had recently struck out on his own. Bluth’s studio, operating under a brutal 16-week deadline, contributed animation of unprecedented quality for gaming, funded in part by a $3 million budget—astronomical for 1983.

Cinematronics, known for vector-based arcade games like Asteroids, agreed to manufacture and distribute the title in exchange for a stake in the venture. The result was a marriage of disparate worlds: AMS’s programming expertise met Bluth’s cinematic artistry, all powered by Pioneer LD-V1000 LaserDisc players. This technology was both a breakthrough and a vulnerability. LaserDiscs offered vastly superior storage over cartridges, enabling FMV sequences that looked like “hand-drawn cartoons,” but they imposed severe constraints. Players had mere seconds to input commands, as the laser assembly hunted for specific frames across the disc. The strain on hardware was immense—players often failed after 650 hours of operation, and European Atari-manufactured versions used metal-backed discs to prevent warping.

The game’s release coincided with a dire period for arcades, plagued by oversaturation and waning interest. Yet Dragon’s Lair became a savior, drawing unprecedented crowds despite being the first game to cost 50 cents per play. Its debut at the 1983 Amusement Operators Expo generated such buzz that Cinematronics pre-sold 3,500 units, effectively financing production. This context—the industry’s desperation for innovation and the game’s position as a “lifeline”—underscores why Dragon’s Lair became more than a product; it was a symbol of arcade resurgence.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Dragon’s Lair‘s narrative is deceptively simple, yet its execution elevates it to a theatrical experience. The story, framed by Michael Rye’s baritone narration in the attract mode, follows Dirk the Daring—a bumbling, endearingly inept knight—on his quest to rescue Princess Daphne from the clutches of the dragon Singe, imprisoned in the wizard Mordroc’s castle. This setup is pure fantasy trope, but the game’s brilliance lies in its delivery. The plot unfolds through a series of “rooms,” each a self-contained vignette filled with hazards: falling ceilings, tentacled monsters, and labyrinthine traps.

Characters are defined by archetypes, yet imbued with surprising depth. Dirk, voiced by editor Dan Molina, is the antithesis of traditional video game heroes. His movements are clumsy, his timing perpetually off, and his reactions to danger range from startled gasps to resigned sighs. This humanizing touch transforms him from a mere avatar into a relatable protagonist, whose failures are as entertaining as his rare successes. Princess Daphne, voiced by Vera Lanpher Pacheco, embodies the “damsel in distress” trope with playful subversion. Her exaggerated swoons and breathy coos—inspired, per Don Bluth, by Playboy magazine poses—add a layer of campy humor, though they also drew criticism for sexism. Singe, the dragon, is less a character and more a force of nature, whose lethargy contrasts with the castle’s frenetic chaos.

Dialogue is sparse but purposeful. Beyond the narrator’s exposition, interactions occur through visual cues and sound effects—a grunt from Dirk, a giggle from Daphne. This minimalism forces players to “read” the animation, heightening immersion. Thematically, the game explores heroism through absurdity. Dirk’s constant near-death mishaps—dodging boulders, outmaneuvering ghosts, and evading collapsing staircases—transform peril into slapstick. The underlying message is that heroism isn’t flawless courage but resilience in the face of ridiculous adversity. This juxtaposition of high fantasy and low comedy creates a unique tonal identity, making Dragon’s Lair as much a comedy of errors as it is an epic quest.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Dragon’s Lair is a masterclass in constrained interactivity, built entirely around Quick Time Events (QTEs). Players control Dirk not through direct movement but through reflexive inputs: a joystick for directional dodges or a sword button for combat. Each “room” presents a predetermined sequence where timing is paramount. A flick left might avoid a swinging pendulum, while a sword slash could deflect a spear. Failure results in elaborate, often humorous, death scenes—Dirk dissolving into bones, being crushed by boulders, or consumed by lava. These moments, while punishing, are also spectacles, turning failure into part of the experience.

The game’s structure is deceptively complex. Contrary to popular belief, levels aren’t truly random but follow a dynamic algorithm based on player skill. Three cycles group rooms, with the game selecting uncompleted levels from earlier cycles. If Dirk dies, he progresses to the next room in the current cycle, but must eventually revisit failed rooms. This system creates emergent replayability, though home ports often simplified it into linear paths.

Innovations are balanced by significant flaws. The reliance on LaserDisc technology meant “blackout” delays between scenes, breaking immersion. Controls required pixel-perfect timing, with no margin for error—home versions sometimes added flashing buttons or infinite lives to mitigate this. Character progression is nonexistent; Dirk gains no abilities, and the game offers no stats or upgrades. The UI is minimalist, mirroring the arcade cabinet’s joystick and button, but later ports adapted to various controllers, from the Sega CD’s pad to the Kinect’s motion sensing.

Ultimately, Dragon’s Lair‘s gameplay is less about “playing” and more about “performing.” Mastery involves memorizing sequences, turning each playthrough into a tense ballet of inputs. While this design alienated players seeking traditional agency, it pioneered a template for narrative-driven games where