- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Dice Multi Media Europe B.V., Electronic Arts, Inc., Sold Out Sales & Marketing Ltd., Virgin Interactive Entertainment, Inc.

- Developer: Intelligent Games Ltd, Westwood Studios, Inc.

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Real-time strategy

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 74/100

Description

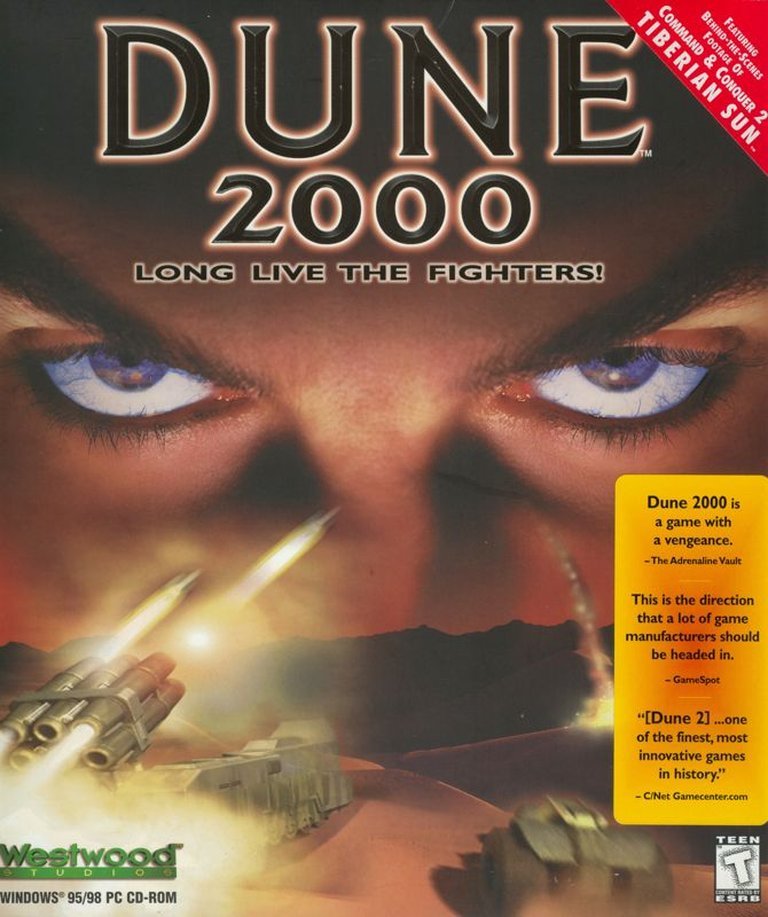

Dune 2000 is a real-time strategy game and a remake of the classic Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty, set on the desert planet Arrakis from the Dune universe. Players command one of three rival houses—the noble Atreides, the insidious Ordos, or the brutal Harkonnen—each with unique units, tactics, and alliances, in a war for control of the valuable spice melange. The game features updated 16-bit graphics, live-action cutscenes, and iconic elements like sandworms, the Fremen, and the planet’s harsh environment.

Gameplay Videos

Dune 2000 Free Download

PC

Dune 2000 Cracks & Fixes

Dune 2000 Patches & Updates

Dune 2000 Mods

Dune 2000 Guides & Walkthroughs

Dune 2000 Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (84/100): What a classic! I loved this game from the start to finish! Need to have a remake!

imdb.com (70/100): Decent storyline and expansion of the dune universe

mobygames.com (68/100): It’s an improvement on Dune 2, no question.

Dune 2000 Cheats & Codes

PlayStation

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| O O O triangle, triangle, X | Be the Emperor |

| Left, Left, Down, R1, R2 | Unlock Invincibility |

| Square, Circle, X, Triangle, Triangle, Square | Reveal Entire Map |

| X, Square, Triangle, Circle, Square, X | Free Money |

| [], O, X, /, /, [] | Show full map |

Dune 2000: The Spice Must Flow—A Historic Remake Caught Between Sand and Stars

As a historian of the real-time strategy genre, few titles present as fascinating a case study as Dune 2000. It stands at a pivotal crossroads: a remake of the seminal Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty (1992)—the game that laid the foundational blueprint for the entire RTS genre—released in 1998, a year that also saw the launch of StarCraft, a title that would redefine competitive play and narrative integration. Dune 2000 is not merely a game; it is a fossilized snapshot of a developer’s (Westwood Studios) relationship with its own legacy, the commercial pressures of a licensed property, and the rapidly evolving expectations of PC gamers at the close of the 20th century. This review will dissect its creation, mechanics, narrative fidelity, and contested legacy, arguing that while Dune 2000 is a historically important title for preservation, its execution represents a critical inflection point where Westwood’s creative momentum stalled, leaving a game that is simultaneously reverent and profoundly reactive.

2. Development History & Context: A Bridge Built on Old Beams

Dune 2000 was developed by Intelligent Games under the production oversight of Westwood Studios, with Lewis S. Peterson and Kevin Shrapnell serving as producers and designers Randy Greenback and James Steer leading the design. The core programming team included Sunlich Chudasama, Simon Evers, and Martin Fermor, while the distinctive art was crafted by Richard Evans and Matthew Hansel. Crucially, the legendary composer Frank Klepacki returned to score the game, linking its auditory identity directly to the iconic sounds of Dune II and the Command & Conquer series.

The technological context is paramount. By 1998, Westwood’s in-house SAGE engine, powering Command & Conquer: Red Alert (1996), was the industry standard for accessible, sprite-based RTS games. Dune 2000 is, in essence, a Red Alert engine reskin. This decision was both pragmatic and damning. It allowed for a rapid development cycle and native Windows/TCP/IP support—a major upgrade over Dune II‘s DOS constraints. However, it also tethered the game to a visual and systemic framework already two years old, a fatal liability in a year that also birthed the 3D acceleration-driven StarCraft and Total Annihilation.

The gaming landscape was ruthlessly competitive. The RTS genre was no longer Westwood’s private domain; Blizzard’s Warcraft II (1995) and StarCraft (1998) had injected deep faction asymmetry, robust campaign narratives, and tight balance into the formula. Dune 2000 arrived not as a innovator but as a nostalgic artifact, explicitly targeting fans of the 1992 classic. As noted in the source material, the developers’ vision was clear: “Westwood did exactly what it said it would do,” as Next Generation critiqued, but the fundamental question was whether anyone had asked for it. The inclusion of live-action FMV cutscenes, starring John Rhys-Davies (Noree Moneo) and Robert Carin (Hayt De Vries), directly mimicked the successful “Tiberium” aesthetic of the C&C series, attempting to leverage cinematic storytelling to compensate for what was, at its core, a conservative gameplay revision.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Mosaic of Canon and Convenience

The narrative of Dune 2000 is a patchwork that both embraces and betrays Frank Herbert’s dense lore. The setup is pure Dune: Emperor Frederick IV (an invention not in the novels, where Shaddam IV reigned during Leto’s time) declares a free-for-all on Arrakis, tasking the Great Houses with spice production. The Bene Gesserit, represented by Lady Elara (Musetta Vander), intervenes by selecting the player-character “commander” based on a vision of a potentially positive future—a direct nod to the Sisterhood’s millennia-long breeding program.

Faction Narratives:

* House Atreides: Led by a Duke (implied to be Leto, creating timeline confusion), with Mentat Noree Moneo. Their story emphasizes alliance with the Fremen, air superiority via Ornithopters and the Sonic Tank, and a “humane” approach to warfare. This aligns with the novel’s portrayal but simplifies the political and ecological complexities.

* House Harkonnen: The Baron’s forces are depicted as genetically and morally degraded, relying on brute force, Devastator Tanks, and the apocalyptic Death Hand missile. Their Mentat, Hayt De Vries, is a Tleilaxu-grown ghola—a deep-cut lore element that pleases purists but is narratively underdeveloped.

* House Ordos: This is the game’s most significant and controversial invention. Not from Herbert’s novels but from the non-canon Dune Encyclopedia, Ordos is a mercantile, paranoid house from an ice planet (later named Sigma Draconis IV). Their gameplay revolves around sabotage (Saboteurs) and psychological warfare (the Deviator tank). Their inclusion is a clear gameplay-driven decision to create a third distinct faction, but it fundamentally alters the political landscape of the Dune universe, introducing a major power absent from the source material. Their insignia is even incorrectly borrowed from House Wallach, a trivia note highlighting the development’s casual relationship with canon.

Cinematic Presentation & Thematic Gaps: The FMV cutscenes are a double-edged sword. Performances, particularly John Rhys-Davies, are praised in reviews for their gravitas and “Lynchian” aesthetic, successfully evoking the 1984 film’s tone. However, the narrative substance is thin. The strategic intrigue, philosophical musings on prescience, ecology, and human potential that define Herbert’s work are entirely absent. The story is a standard “conquer the planet” boilerplate dressed in Dune drag. The Fremen are reduced to “Death Commandos” (incorrectly called “Naib” in one cutscene, a title for a sietch leader, not a warrior) and cloaked infantry units, stripping them of their profound cultural and messianic role. Reviews consistently note this failure: GameSpot called it “a C&C-Dune Alert,” while a player review lamented the lack of “diplomacy, intrigue, Bene Gesserite influence, or Weirding Way.”

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Comfortable Chains of Convention

Dune 2000’s gameplay is a direct inheritor of the Dune II/C&C family tree, with all the strengths and glaring weaknesses that implies for 1998.

Core Loop & economy: The loop is unchanged: build a Wind Trap for power, construct a Barracks and Factory, deploy a Mobile Construction Vehicle (MCV) to lay concrete foundations (a unique mechanic where buildings deteriorate without it), establish a Refinery and Spice Harvesters to mine “spice” for “Solaris,” and amass an army to destroy the enemy. The concrete requirement is a strategic nuance that adds a layer of base-defense planning, forcing resource allocation for infrastructure.

Faction Asymmetry (The Good): This is where the game shines. Each house has a distinct identity and set of tools:

* Atreides: Sonic Tank (area-denial/anti-infantry), Ornithopters (air scout/attack), Fremen guerrillas (cloaking, high damage).

* Harkonnen: Devastator Tank (heavy armor/firepower), Death Hand missile (EMP-like building destroyer), Sardaukar (added via patch 1.06; elite infantry).

* Ordos: Deviator Tank (mind-control projectile), Saboteur (stealth unit that destroys buildings), Raider Trike (faster scout). They also access the Missile Tank via the Starport.

This asymmetry encourages different tactical approaches, a clear evolution from the near-identical factions of Dune II.

Interface & Innovations (The Mixed): The shift to a Red Alert-style interface is the single most significant upgrade. Band selection (box-dragging to select multiple units) is finally implemented, a basic QoL feature missing from the original. The radar map is now functional and persistent. However, the system remains primitive. No unit production queues means constant babysitting of factories. Pathfinding is notoriously poor, with units frequently getting stuck or taking inefficient routes—a persistent complaint across reviews. No waypoints or advanced formation controls limit large-scale maneuvering. The Starport is a brilliant mechanic: a neutral structure allowing players to purchase units (sometimes exclusive ones like the Ordos Missile Tank) at a fluctuating market price, introducing a risk/reward economic layer absent in Dune II.

AI & Mission Design (The Bad): The AI is universally panned as simplistic and exploitable. The “trike rush” (fast early attack with scout units) is cited as a guaranteed win on many maps, a sign of poor economic and defensive scaling. Mission design is criticized as monotonous and derivative. As Bravo Screenfun noted, missions largely follow the “build base, gather resources, attack enemy base” template with only terrain and tech-level variations. There is a lack of varied objectives (escort, holdout, sabotage) that defined later RTS campaigns.

Balance & Legacy: The attempt to give Dune II‘s imbalanced factions (Ordos was notoriously weak) a fairer footing is appreciated. Yet, against the backdrop of StarCraft‘s rock-paper-scissors unit balance and distinct tech trees, Dune 2000 feels simplistic and unbalanced in a different way. The Harkonnen’s raw power versus the Atreides’ combined arms feels less like a dynamic equilibrium and more like a brute-force vs. gadget contest.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: A Tony that Carries the Weight

When Dune 2000 succeeds, it is almost entirely due to its presentation and atmosphere, which faithfully translates the Dune aesthetic as interpreted by David Lynch’s 1984 film.

Visual Direction: The graphics, while derided as “drab” and “dated” (640×400 resolution, limited tilesets), have a cohesive, gritty realism. Units and buildings are clearly inspired by the film’s production design—the Harkonnen castle is a grotesque fascist megastructure, the Atreides buildings feel organic and rounded. The sandworms are a particular highlight, rendered with a sense of scale and menace. The single, monotonous desert tileset is a major flaw, creating visual fatigue and eliminating geographical strategic variation. The lack of terrain types (no rock, no water on Arrakis, but also no different sand colors or elevations) makes maps feel samey.

Sound Design & Music: Frank Klepacki’s score is a masterpiece of atmospheric RTS music. Tracks like “Spice Mining” and “Dune Theme” are iconic, dynamically shifting between ambient tension and martial crescendo. It is arguably the game’s most enduring and praised element. Sound effects are sharp and satisfying, from the roar of a sandworm to the报告的 of a Deviator shot. The FMV cutscenes, though live-action, benefit from practical sets and costumes that strongly echo the film, creating a powerful sense of place.

Atmosphere vs. Depth: The game perfectly captures the surface-level aesthetic of Dune: the deserts, the stillsuits, the ornithopters, the oppressive heat. It utterly fails to capture the thematic depth: the ecology of Arrakis, the politics of water as currency, the messianic Fremen culture, the philosophical weight of the Spacing Guild and Bene Gesserit. The world feels like a beautiful, empty soundstage.

6. Reception & Legacy: The Quintessential “Disappointment”

Contemporary Reception (1998-1999): The critical reception was mixed-to-negative, with an average critic score of 68% (MobyGames) and 58-61% on GameRankings. The consensus was captured by GameSpot (5.5/10) and Next Generation: it was a competent but dated remake that added little to the genre and failed to leverage its prestigious license. Common criticisms: dated graphics (especially compared to StarCraft), simplistic AI, repetitive missions, and a failure to innovate.

However, there were defenders. German magazines like PC Action (86%) and GameStar (84%) praised its faithful adaptation and the strength of its core mechanics, acknowledging that the Dune II formula retained its appeal. AllGame gave it 4.5 stars, calling it “an instant classic” for fans. This split highlights the core divide: was it a remake for nostalgia, or a new product in a modern market?

Player Reception Over Time: Player scores on MobyGames (3.5/5) and Metacritic (8.4) are notably more positive than contemporary critic scores, suggesting a cult following or reappraisal among those who played it with lower expectations or in the context of its lineage. Reviews on IMDb and Metacritic frequently cite its “fun factor,” the strength of its FMVs, and its role as a “solid” RTS, albeit not a genre leader.

Legacy and Influence: Dune 2000’s legacy is complex:

1. A Commercial Stopgap: It served its immediate purpose: to capitalize on the renewed interest in Dune following the 1984 film’s cult revival and the prequel novels. It was a low-risk, high-recognition product.

2. The Bridge to Emperor: Battle for Dune: Its direct sequel, Emperor: Battle for Dune (2001), is a far more ambitious 3D RTS. Critically, Emperor canonized the Ordos ending from Dune 2000, making their victory part of the official (Westwood) Dune timeline—a bold, controversial move that retroactively validated the non-canon house’s inclusion.

3. The “What Could Have Been” Artifact: For many, it represents a missed opportunity. The resources spent on a Dune II remake could have been used to create a true sequel or a more innovative Dune game. Its release just before StarCraft made its shortcomings glaring. It signaled that Westwood, for all its C&C success, was becoming creatively conservative.

4. Preservation and Fan Legacy: The game’s continued availability through re-releases (EA Top Ten Packs) and, most importantly, support in the OpenRA project (a fan-run engine recreation for classic Westwood RTSes) ensures its technical preservation. It remains a playable artifact of the pre-3D RTS era.

5. A Benchmark for Remakes: It is often cited in discussions about “faithful” versus “reimagined” remakes. It chose the former path—update the presentation, keep the gameplay nearly intact—which pleased some purists but alienated those expecting a Civ II-level depth increase for a classic.

7. Conclusion: A Flawed Relic of a Franchise at a Crossroads

Dune 2000 is a game of profound contradictions. It is a loving, technically competent update of the game that invented the real-time strategy genre, retaining the core gameplay loop that hooked millions in 1992. Its faction design, thanks to the inclusion of the Ordos, offers more strategic variety than its predecessor. Its FMV cutscenes and Frank Klepacki’s timeless score create an atmosphere thick with Arrakis’s grit and grandeur.

Yet, it is also a game that feels born obsolete. Built on a two-year-old engine, it arrived visually and mechanically outpaced by StarCraft. Its AI was rudimentary, its mission design derivative, and its narrative a thin veneer of Dune iconography over a generic conquest plot. It exploited its license and its fans’ nostalgia without offering the transformative experience a true sequel or a Civ II-style reimagining might have provided.

In the grand tapestry of video game history, Dune 2000 is not a masterpiece. It is, however, a significant and necessary artifact. It represents the moment Westwood Studios chose to look backward—to remake its own foundational hit—at the exact moment the genre was leaping forward. It is the last gasp of the pure Dune II/C&C engine design philosophy before the 3D revolution and the rise of Blizzard’s intricate balance. To play Dune 2000 today is to engage with a game caught in the tectonic plates between past and future: holding the familiar shape of the old world, but trembling with the seismic shifts happening just beneath its surface. For the historian, it is indispensable. For the player in 1998, it was a disappointment. For the modern enthusiast, it is a fascinating, flawed, and still enjoyable relic of the Spice that must, against all odds, still flow.