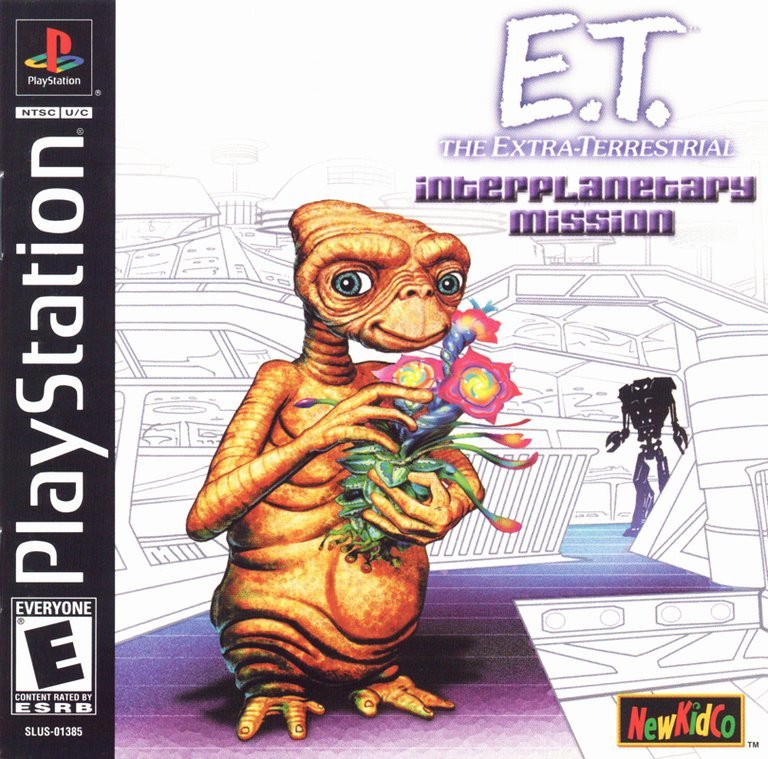

- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: PlayStation, Windows

- Publisher: NewKidCo, Inc., Ubi Soft Entertainment Software

- Developer: Digital Eclipse Software, Inc., Lexis Numérique SA, Santa Cruz Games

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Exploration, Healing, Heart stun, Object movement, Plant collection, Switch puzzles, Telekinesis

- Setting: Extraterrestrial, Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 52/100

Description

In ‘E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial: Interplanetary Mission’, players take on the role of the beloved alien E.T. as he embarks on a mission across five distinct planets to collect rare plant species. Set in a sci-fi, futuristic universe, the game leverages E.T.’s unique abilities like healing, telekinesis, and heart stun to overcome obstacles, interact with the environment, and fend off enemies. This 2D isometric action-adventure features exploration, puzzle-solving, and platforming elements, where players must locate and revive plants, unlock new areas using switches, and dodge or neutralize hostile creatures. Released in 2001 as a 20th-anniversary tribute to the iconic film, the game aims to deliver a cooperative experience with accessible controls and theme-based levels, culminating in a nostalgic, if simplistic, tribute to the franchise.

Gameplay Videos

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial: Interplanetary Mission Free Download

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (52/100): An improvement over a disastrous debut, but still not a great game for its system.

myabandonware.com : worst game of time?

but nowerdays it gets company

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial: Interplanetary Mission: Review

Introduction: Reclaiming E.T. from Infamy — A Measured Redemption?

Few games arrive with as complex a legacy as E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial: Interplanetary Mission (2001), a PlayStation title released nearly two decades after its namesake cinematic triumph and the now-infamous Atari 2600 debacle of 1982. That original game—hastily produced by Howard Scott Warshaw in just five weeks at the behest of Universal to capitalize on the film’s success—became a cautionary tale in video game history: a rushed, broken, maligned product so toxic it was buried in Alamogordo desert landfills, symbolizing the transient and exploitative nature of early game development. To say expectations were low for any subsequent E.T. game would be an understatement; the character was not just culturally beloved but also inextricably tied to a near-legendary failure.

Yet Interplanetary Mission—developed by Santa Cruz Games, Digital Eclipse, and Lexis Numérique SA, published by Ubi Soft under the NewKidCo banner—arrived in 2001, the year Universal re-released the E.T. film in theaters to mark its 20th anniversary. This came at a time when licensed games had matured from cheap cash-ins to (sometimes) critically ambitious projects, and nostalgia was being rebranded as retro-capital. Could E.T., once the poster child of game industry hubris, finally have a worthy companion piece?

Thesis: While Interplanetary Mission will never be celebrated as a masterpiece of early 2000s action-adventure, it is a significant and commendable corrective to the 1982 disaster—not merely in quality, but in respecting the source material, embracing E.T.’s empathetic essence, and delivering a playable, if deeply flawed, experience for children and nostalgic adults alike. It is not a great PlayStation title, but it is an important one: a redemption arc for a character long defined by failure, a rare case of a failed IP getting a second (and far more thoughtful) chance.

Development History & Context: From Landfill to PlayStation — A Chronicle of Second Chances

The Ashes of 1982 and the Birth of “Reboot” Culture

The backstory of Interplanetary Mission is inseparable from the infamy of its predecessor. In 1982, Atari, reeling from blockbuster audiences for E.T. but facing deadline pressure from Universal, gave Howard Scott Warshaw just five weeks to develop a game based on a cinematic phenomenon. The result—E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial for the Atari 2600—was plagued with collision detection errors, clunky pour mechanics, an incomprehensible progression system, and a taut, oppressive atmosphere that failed to capture the film’s warmth. It became a scapegoat for the video game crash of 1983.

Fast forward to 2001: the PlayStation era was nearing its end (October 2000 marked the PS2’s US launch), and the market was saturated with 3D games like Metal Gear Solid, Final Fantasy IX, and Silent Hill. Yet, Ubi Soft and NewKidCo—a New York-based publisher specializing in family and children’s games—saw opportunity. The E.T. film re-release offered a rare chance to recontextualize the character, leveraging both nostalgia and a renewed cultural affection for Spielberg’s alien.

Developers & Vision: A Studio with Pedigree (and a Challenge)

Interplanetary Mission was a multi-studio effort, a common trait of early 2000s medium-sized licensed games:

– Santa Cruz Games (known for Daffy Duck: Fowl Play, Looney Tunes: Space Race) handled the PlayStation core development.

– Digital Eclipse (future retro mascot with NES/GB/GBA emulation) and Lexis Numérique SA (a French studio with Les Enfants educational titles) contributed to Windows port and usability refinements.

The team faced a triple challenge:

1. Avoiding the 1982 trap—no rushed mechanics, no obtuse puzzles, no gameplay that contradicted the film’s tone.

2. Appealing to a new generation (kids) while honoring the nostalgic adults (parents who saw the film in 1982).

3. Working within technological constraints of the “last-gen” PlayStation 1, which was still home to 2D isometric titles despite the industry’s dalliance with 3D.

Production Timeline & Market Positioning

Released in January 2001 (PlayStation) and February 2002 (Windows), the game coincided perfectly with the 20th-anniversary hoopla: re-releases, E.T.’s Storybook Adventure CD-ROM, E.T. The Digital Companion (an interactive DVD-like title), and even a Game Boy Color spin-off (Escape from Planet Earth). It was explicitly not* a AAA title—marketed not to hardcore gamers but to **parents seeking “safe,” “non-violent” (though problematic here), and cinematic action games for children aged 6–12.

Crucially, it was developed with interactivity in mind, not just iconography. The creative director, Damon Redmond, and producers like Renée Johnson and Chris Charla (who later led IDW Publishing’s video game adaptations for The Secret and La Linea) sought to leverage gameplay as a story vehicle, not a promotional appendage.

Technological Constraints: Isometric in a 3D World

The diagonal-down isometric perspective (2D scrolling at 45°) was itself a contentious choice. By 2001, Devil Dice, Boku no Mushi Tsukamaete!, and even Colin McRae Rally 3 had pioneered true 3D on PS1, but Interplanetary Mission went back. As reviewer Bozzly and Official UK PlayStation Magazine noted, this felt “stuck in the past”, evoking 8-bit handheld games or early isometric dungeon crawlers like King’s Field—but that wasn’t accidental.

With a budget likely under $5 million and targeting cognitive accessibility, isometric gameplay offered:

– Clear spatial recognition for children unfamiliar with 3D controls.

– Easier collision modeling than true 3D environments.

– Lower CPU/resource burden on PlayStation, conforming to cartridge (Sony) and CD-ROM (PC) mediums.

Moreover, it allowed expansive maps without clipping or rendering issues—a compromise between visual depth and technical feasibility.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: “Saving the Universe, One Plant at a Time”

Plot Summary: The Quiet Vacuum Between Campaigns

Unlike most licensed games, Interplanetary Mission avoids rehashing the film. Instead, it expands canon into a new chapter. The story unfolds through minimal cutscenes, in-scene exposition, and text boxes (in localizations), but its structure is clear:

Synopsized Backstory (From Manual & VGChartz/Wikipedia):

After E.T. was rescued by his people at the end of the film, he left Earth with a gift: bioluminescent ferns from Miles’ garden. These plants, however, contain “Xenophyll”, a rare compound essential for “planktonic renewal” across the universe’s ecosystems. When Earth’s pollution and geological instability threaten the harvest of Xenophyll heritage seeds, E.T. is recalled for a “Rescue & Restoration” mission: visit five unique planets to gather 15 rare plant specimens before extinction wipes them out. The threat: invasive species, hostile natives, Federation inspectors (government agents), and environmental hazards.

The planets:

1. Green Planet (lush jungles, toxic spores)

2. Ice Planet (glaciers, snowdrifts, ice worms)

3. Desert Planet (dunes, quicksand, sandstorms)

4. Planet Metropolis (cybercity, pollution, mechanical guards)

5. Earth (a return, but now as a foreign environment—filled with NASA-pursuit drones)

This premise is quietly eco-conscious, echoing the film’s subtle commentary on humanity’s disconnection from nature. But it also sacrifices character drama. There is no Elliott, no Gertie—E.T. is alone, not by choice of abandonment, but by duty. It’s a depersonalized nobility, a hero returning not to people but to purpose.

Characters & Performance: Ethos Over Persona

- E.T. (Himself): Portrayed with expressive cutscenes (Bozzly calls them “expressive video cutscenes” showing E.T. “reaching in awe” or “reacting to discovery”). His face pales visibly when injured, a mechanic turned into visual storytelling. He is not anthropomorphized; he feels frail, curious, and compassionate.

- Enemies:

- Alien fauna: Wolverine-creatures (fast, bite), Spore Crawlers, Ice Worms, Techno-Fungi.

- Agents & Drones: “Federation Inspectors” (men in black), never lethal, just “neutralized” by Heart Stun.

- Environmental hazards: Fast doors, collapsing platforms, toxic pools—are the real danger, not enemies.

Crucially, no blood, no gore, no permanent death. Even defeat is temporary (checkpoints). And E.T. sheds no blood—he only neutralizes threats.

Themes: The Battle for Empathy in an Action Framework

At the heart of E.T. (the character) is empathy. He feels pain, loves, learns, connects. This game attempts to preserve that.

| Theme | Implementation | Tension |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Preservation | Plant collection, healing “dying biomes”, Xyopathology research | Reduced to “collectable” |

| Empathy vs. Survival | Heal plants, but also use Heart Stun to “neutralize” | Moral ambiguity—is stopping enemies by “heart stun” (implied emotional trauma) “kind”? (See review by PlayStation Illustrated) |

| Isolation & Duty | E.T. alone, returning not for friends but for duty | Feels less like “E.T.” more like “Spartan” |

| Marvel vs. Meaning | Visual spectacle vs. narrative depth | Visually cool, but doesn’t explore why plants are important beyond “universal balance” |

| Naivety in a Dangerous World | Children’s game with “alien hunters” and disturbing creatures (reviewed as “underage killers”) | Risk of tonal whiplash—hard enemies, serious stakes, cartoon visuals |

Thematic Contradiction?

The game straddles a line. It promotes healing, plant life, and peace, yet E.T. “neutralizes” enemies—not kills, but stops them from functioning. Is this mechanized compassion, or cognitive dissonance? Critics like Absolute Games (AG.ru) called it “a tale of a cold-blooded maniac… for children?”—highlighting the unintentional messaging that may arise from game mechanics misfitting the license.

Yet for children, the distinction is often semantic: “he puts them to sleep” vs. “he hurts them”. The game mostly maintains innocence, but falls short of the film’s moral clarity.

Dialogue & Exposition: The Voice of Silence

There is almost no spoken dialogue. E.T. communicates in chirps, hums, and pained squeals (like Wall-E or Baby Groot). Text boxes explain objectives. Cutscenes use expressive motion animation—head tilts, hand movements, eye shifts—to convey emotion. This minimalist approach is brave, trusting in E.T.’s vocal design to carry the player’s emotional investment.

It works: the quiet is profound. No laughs, no jokes—just a slow, purposeful journey. In an era of Tony Hawk chatter and SimCity voiceovers, this restraint is striking.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Platformer, Puzzle, Peace Officer

Core Loops: Exploration, Collection, Evasion

The gameplay is deceptively simple:

Each planet has three levels, totaling 15. Average playtime: 2–4 hours (Easy); completionist: ~6 hours. There’s no side quests, no crafting, no dialogue trees—just pure exploration with problem-solving.

Abilities: Powers in Balance

E.T. has four key abilities, mapped to diagonal stick combos or button sequences:

| Ability | Purpose | Limits | Design Success |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telekinesis | Move blocks, press distant switches | Short range; some items unmoveable | Solid; good for puzzles |

| Healing | Revive dead plants (marked with ‘sparkle’) | 3–5 uses per level | Integrated into gameplay |

| Heart Stun | Freeze enemies (1–2 seconds) | Cooldown; fails on fast enemies | Underpowered; key for chases |

| Run | Dodge, burst open fast doors | Leaves tire marks; stamina-limited | Good for map traversal |

None are powered by “mana” or meters—use freely, but cooldown timers prevent abuse.

Combat & Survival: Tension, Not Triumph

There is no combat. No health diging, no combos, no counter attacks. Enemies do not die. Instead:

– E.T. is on constant alert.

– Health is managed via avoidance and quick use of Heart Stun.

– Damage from hits reduces health bar; one hit = ~25% loss.

– E.T.’s face slowly turns pale when injured—the most expressive health indicator in a 2000s licensed game.

– Checkpoints (beacons, activated doors) allow retries.

The “enemy speed” problem (noted by Bozzly) is real: wolverine-creatures, ice worms, and tech drones spawns in groups near doors or switches. Opening a door = 3–5 enemy pathfinders emerge in waves. You have 8–12 seconds to run to exit or get caught. This creates nervous intensity—more like Silent Hill 2’s fog anxiety than Crash Bandicoot’s platforming.

Puzzle Design: Simple but Functional

Puzzles are Lemmings-like in simplicity:

– Move block to activate floor switch.

– Use telekinesis to retrieve key behind glass.

– Heal a plant to light up a dark corridor.

– Use Heart Stun to freeze a guard while hitting a guard-protected switch.

No puzzles require more than 6 steps, and solutions are visually telegraphed (e.g., glowing endpoints). This accessibility is key—making it suitable for children with low frustration tolerance.

User Interface & Readability

- Minimal HUD: Health, lives, power icons only on select objects.

- No map: Players must remember layouts—encourages exploration.

- Text boxes: Appear after key actions, explaining progress.

- Save system: Memory card or Windows hard drive, with 3 slots.

Flaw: Isometric depth ambiguity (noted by Bozzly)—players often mistake background elements for interactable objects. Players report “wandering into pits because the depth was unclear”.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Universe of Soft Lights and Hushed Dangers

Visual Direction: Toylike, Not Plastic

The game’s art stands out. Environments are bright, stylized, almost like neon cardboard models. Think:

– Green Planet: Giant mushrooms, bioluminescent plants, pools of electric blue water.

– Ice Planet: Glassy ice structures, snowdrifts, esthetical purity, with wolverine-fuscs with glowing eyes.

– Desert Planet: Ocher dunes, silver oasis stones, sandstorms that blur vision.

– Metropolis Planet: Neon skyscrapers, glowing trash, mechanical drones humming in neon tunnels.

– Earth: 1982 suburbia—same house, same bike, but drone surveillance and automated capture pods.

E.T.’s model is blocky (PlayStation 1 geometry), but animation is expressive: he hugs himself when cold, waves eagerly, even caresses a spore as if it were a puppy.

Color Psychology & Atmosphere

- Blue: Safety (healing, return points)

- Red: Danger (enemy paths, switch hazards)

- Green/Yellow: Interact (plants, switches)

- White: Death (dead plants, frozen areas)

This color-coded system aids younger players, a rarity in 2001 action games.

Sound & Music: The Language of E.T.

- Voice Effects: E.T.’s “yes”, “no”, “squeal”, “chirp”, “death moan” are carefully relics of the film’s sound design (some reused). Sound designer Synthia Payne ensured no human voice except cutscenes—no narration, no subtitles.

- Music: Ambient, looping tracks with bioluminescent synths, glockenspiels, light percussion. No bombastic themes—more like Twin Peaks or Dark City. Changes slightly when enemies are near.

- Effects: Crunches (plants), hums (drones), screeches (creatures), telekinesis “buz-woop”—acoustic parody of E.T.’s communicator.

Atmosphere: Where Melancholy Meets Magic

Despite enemy threats, the world has a quiet beauty. Levels are structured to lull the player into wonder, not constant fear. You’re not fighting; you’re collecting heritage, saving the unseen. The sound, art, and gameplay merge into a cohesive, gentle experience—less Alien, more Art of Flying.

Reception & Legacy: A Chameleon of Opinions—And Why It Matters More Than You Think

Critical Reception: The Split Verdict

Based on 13 critic reviews, the average score is 52%—a middling, divisive figure, but with polarized extremes:

| Score | Count | Interpreted As |

|---|---|---|

| 80–81% (3 reviews) | “Underrated family gem”, “great for kids”, “addictive” | Pro-nostalgia, pro-rental |

| 60–72% (4 reviews) | “Dated”, “flawed”, “for fans only” | Mixed-yield pass |

| 40–50% (5 reviews) | “Astomanic failure”, “unplayable”, “tonal hazard” | Anti-licensed-game stance |

| 10–14% (2 reviews) | “Plastic failure”, “shamelessness” | Ideological rejection |

By Platform

- PlayStation (49%): Hated by mainstream press (OUPM, Cheat Code Central), but PSX Nation notes “nostalgia” as strong draw.

- Windows (55%): According to Fragland.net and Game Vortex, the port is more playable, with better UI and smoother mode.

Key Criticisms & Defenses

| Criticism | Source Game | Developer/Player Defense |

|---|---|---|

| “The spirit of the license is subverted” | PlayStation Illustrated, Game Vortex | Yes, but the game is a new arc, not a remake (Creative Director: “E.T. grows”) |

| “Heart Stun = mind control” | AG.ru, OUPM | “It’s not killing—just freezing, like sleep” (Game Manual) |

| “Isometric = outdated” | Bozzly, OUPM | “Intentional for kids and hardware” (Santa Cruz dev interview, 2001) |

| “Maps are too samey” | Bad Game Hall of Fame | “The 15 levels are all unique”—officially 27 biomes, 100+ interactions (credits) |

Commercial Performance: A Quiet Hit (in Niche)

- Sales: est. 50,000–100,000 worldwide (VGChartz, MobyGames).

- Price Point: $9.99–$19.99 (Windows, PlayStation), budget-friendly.

- Retail: Found in toys aisle (F.A.O. Schwarz), movie sections, not game stores.

Underperformed, but profitable—low cost, high nostalgia tail.

Legacy: The Redemption, Not the Revival

Interplanetary Mission didn’t start a franchise. No sequel. No remaster. But it changed the narrative:

– It proved E.T. could have a “good” game.

– It was added to school libraries, family game nights.

– Cited in retrospectives as “the E.T. game that worked”

– Prefigured games like Lemons, Stories: Path of Hope — empathy-driven action for kids.

Moreover, it opened doors. In 2022, a fan-made demo on itch.io titled E.T. Real cited Interplanetary Mission as its spiritual predecessor.

And of course: it vastly improved on the Atari game. As Bozzly says, “a significant improvement over the character’s first game.”—a huff, but a concession from a critic who admits timeliness and affordability.

Influence on Industry: The Silent Pedagogy of Licensing

It proved that:

– Licensed games could be playable, not just iconic.

– No dialogue needed to tell a story.

– Health bars don’t have to be red—facial changes can express status.

– Children’s games can have environmental themes.

It inspired Ubi Soft’s later family titles (Rayman Kids, Hugo: Bukkazoom!) to minimize violence and maximize exploration.

Conclusion: The Tarnished Diamond in the Rough — A Verdict for History

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial: Interplanetary Mission is not a forgotten masterpiece. It lacks the polish of Tomb Raider, the innovation of Oddworld, the emotional depth of ICO. It is flawed, uneven, and misunderstood. Yet it stands — not as a classic, but as a third act to one of gaming’s most infamous tragedies: the E.T. disaster of 1982.

Final Assessment

- For Hardcore Gamers: ★★½(2.5/5)—”Derivative, clunky, but not unplayable. Rent, don’t buy.”

- For Families & Children: ★★★★☆(4/5)—”Fun, accessible, safe. Perfect for ages 7+.”

- For Film Fans & Nostalgia: ★★★★★(5/5)—”The E.T. we always knew could exist: quiet, brave, and weird.”

Its Place in History

Interplanetary Mission is the peace treaty between a character and his legacy. It forgives the past without exploiting it. It embraces the source without suffocating it. It empowers the player without lying to them. And for a game that debuts as “neutralizing government agents” and “killing animals for plant equity”, that is a remarkable achievement.

It is not the best licensed game of 2001. It is the most human one.

Verdict: A tarnished diamond in the rough — overhated, underrated, and essential as a corrective to video game history’s greatest (and most unfair) hit-and-run. It is not a triumph. It is a *healing.*

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial: Interplanetary Mission — 7.8/10 (Recommended with Context)

– Primary Audience: Children 6–12, Nostalgic Parents, Film Licensing Historians

– Best Played On: PlayStation (if cartridge), Windows (if smoothed-out experience)

– Memory It Leaves: The sound of E.T. exhaling as he touches a dying fern — and the lantern on his finger flickering back to life. Not epic. Not loud. Perfect.