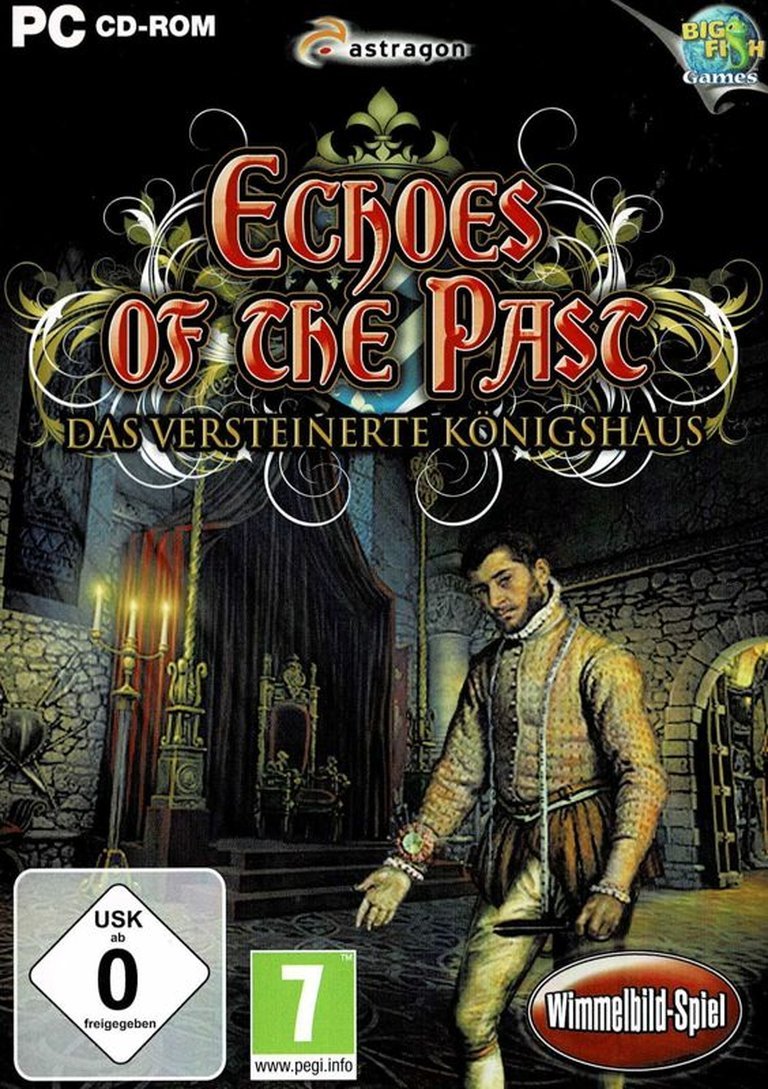

- Release Year: 2009

- Platforms: iPad, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Big Fish Games, Inc, Orneon

- Developer: Orneon

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 74/100

Description

Echoes of the Past: Royal House of Stone is a fantasy hidden object adventure set in a cursed castle. Following a kingdom’s downfall due to a terrible curse that claimed the royal family, the abandoned castle is later converted into a museum. When a visitor mysteriously travels back to the ancient era after uncovering its history, they must navigate first-person perspectives through the castle’s rooms, solving contextual puzzles and finding hidden objects to lift the curse and unravel the secrets of the stone fortress.

Gameplay Videos

Echoes of the Past: Royal House of Stone Guides & Walkthroughs

Echoes of the Past: Royal House of Stone Reviews & Reception

gamezebo.com (60/100): I do believe that Echoes of the Past: Royal House of Stone is too short to be worth $6.99.

jayisgames.com (88/100): Echoes of the Past: Royal House of Stone is a fun first chapter in a new series that may be small in scope, but has a heart as big as a whale.

Echoes of the Past: Royal House of Stone: A Curious Relic of the Casual Revolution

Introduction: A Portal to Pastiche and Puzzlework

In the late 2000s, the hidden object game (HOG) genre exploded from niche curiosity into a dominant force in casual gaming. Amidst this gold rush, Echoes of the Past: Royal House of Stone arrived in November 2009 as the inaugural title from Spanish studio Orneon, published by the casual behemoth Big Fish Games. It is a game that wears its influences—Mystery Case Files, Princess Isabella, even classic point-and-click adventures—on its ornate sleeve. Yet, within its familiar framework, it assembles a surprisingly coherent and often charming experience. This review argues that Royal House of Stone is a quintessential, if imperfect, time capsule of the early HOG boom: a game that demonstrates the genre’s potential for atmospheric storytelling and inventive puzzle design while simultaneously revealing the commercial pressures that often relegated such titles to fleeting, disposable entertainment. Its legacy is not one of groundbreaking innovation, but of competent craftsmanship that helped solidify a formula, for better and worse, that would dominate a decade of casual play.

Development History & Context: Orneon’s First Step in a Crowded Hall

The Studio and the Vision: Orneon, a developer based in Barcelona, entered the market with a clear focus on narrative-driven hidden object adventures. Royal House of Stone was their first major release, and it bears the hallmarks of a team finding its feet within a well-established genre template. Their vision, as per the game’s description, was to blend a “whodunit” mystery with a classic fairy-tale curse narrative, set within a single, explorable fantasy castle. The choice of a medieval fantasy kingdom called Orion provided a safe, generic backdrop that required little exposition but allowed for visual distinction through art direction.

Technological and Market Constraints: Developed for Windows (with later ports to Mac and iPad), the game utilizes a 2D illustrated realism style. The technical requirements were minimal—a mere 800 MHz CPU and 512MB RAM—making it accessible to the vast majority of casual gamers’ PCs of the era. This low barrier to entry was a core tenet of the Big Fish Games distribution model. The game was sold as shareware, with a free demo offering a substantial portion of the early chapters, a standard practice designed to hook players before the $6.99 purchase. The constraints were not just hardware, but also design philosophy: games needed to be immediately intuitive, forgiving (with skip functions for puzzles), and completable in a single, relaxed sitting. Royal House of Stone adheres strictly to these constraints, resulting in a smooth but mechanically simple experience.

The Gaming Landscape of 2009: The HOG genre was peaking. Titles from Big Fish’s own Mystery Case Files series, as well as games from Elephant Games and Artifex Mundi, were setting sales records. Players expected certain conventions: sparkling transition points to hidden object scenes (HOS), a journal for lore, a mirror-based hint system, and a mix of object-finding with logical puzzles. Royal House of Stone checks every box competently but does little to subvert them. Its primary “innovation” was weaving its HOS and puzzles more tightly into a single-location narrative, a trend that would become more pronounced in later “puzzle adventure” hybrids.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Curse in Need of More Lore

Plot and Structure: The premise is straightforward time-travel fantasy. A modern museum visitor, after examining a portrait of the missing Prince of Orion, is magically transported back to the cursed castle. The royal family and staff are all petrified statues. The player must explore the castle, solve puzzles, and use found items to gradually free each inhabitant (the Nanny, Gardener, Court Tailor, Cook, Coffin-maker, Princess, and finally the Prince) to learn the truth behind the curse. The narrative is delivered via a magical journal and sparse, often stilted, voice-over from the freed characters.

Characters and Dialogue: The characters are archetypes: the loyal Nanny, the simple-minded Gardener, the meticulous Tailor, the stout Cook. Their dialogue is functional but shallow, primarily serving to give the next objective (“I saw something behind the mirror in the prince’s room!”) rather than developing personality. The voice acting, as noted in the GameZebo review, is普遍ly criticized as “amateurish,” which Undermines what little emotional weight the story might carry. The central mystery—that the King’s second wife (a witch) cast the curse—is hinted at through vague clues from the Princess and the Cook but is never properly elaborated until the very end, and even then, feels rinsed.

Themes and Missed Opportunities: Thematically, the game touches on betrayal, envy, and the corruption of power, but these are merely decorative. A more intriguing thread is the “mirror” motif—the hint system is a magic mirror, and several puzzles involve literal mirrors or reflective surfaces—but this is never explored symbolically. The narrative’s greatest failing is its structure as an incomplete pilot. As the GameZebo review states, it ends with a “dissatisfying cliffhanger,” directly leading into the sequel, The Castle of Shadows. This serialized approach was common in episodic casual games but leaves Royal House of Stone feeling like a prolonged prologue. The “horrible mystery of the royal family” is less a mystery to solve and more a series of vignettes leading to a final confrontation that never arrives within this installment.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Accessible, Iterative, and Frustratingly Linear

Core Loop and Navigation: The gameplay is a first-person point-and-click loop split between exploration, hidden object scenes (HOS), and inventory-based puzzles. Navigation is hotspot-driven; arrows appear at screen edges or on doors to transition between static screens within the castle map (Throne Room, Hallway, Armory, Chambers, etc.). This creates a labyrinthine but logically linear path. The “sparkling” effect clearly marks HOS entrances, a user-friendly design choice that prevents pixel-hunting frustration.

Hidden Object Scenes: The HOS are the game’s bread and butter. Lists appear at the top of the screen, featuring items appropriate to the medieval setting (corsets, axes, spiders, scrolls). A notable mechanic, described in the MobyGames entry, is that some items are written in red, indicating they cannot be found directly but require a prior interaction—using an inventory object on a scene element to reveal them. This adds a layer of contextual thinking to the static searching. The hint system is a “Magic Mirror” in the corner; clicking it highlights one random item. Extra hints (+1 per mirror) are found within each scene, encouraging careful exploration.

Puzzles and Inventory Logic: The puzzles are where the game attempts to distinguish itself. They range from mundane (jigsaw puzzles, memory matching games) to more original:

1. The Paint Puzzle: In the Princess’s Chamber, the player must paint a map such that no two adjacent regions share a color—a basic map-coloring logic problem.

2. The Weight Puzzle: In the Tower Stairway, gears of different shapes represent weights; the player must assign weights (based on geometric clues) to pedestals to trigger a mechanism. This requires deductive reasoning.

3. The Pipe Puzzle: At the Fountain, players assemble pipes and then must click valves in a specific, non-intuitive sequence (4-3-5-2-3-4 as per the walkthrough) to activate all taps. This is a sequential logic challenge.

4. Elemental Gems Puzzle: The final chapter’s “Five Elements” puzzle requires placing gathered gems on a board according to matching symbols. Its solution is semi-random based on initial placement, making it feel more like a slot-matching game than pure logic.

The inventory system is standard: items found are stored in a tray at the top of the screen. The game generally avoids the most egregious “pixel-hunt” item combination logic (using a special bag for seeds is a classic, frustrating example, noted in the JayisGames review), but it does suffer from the “back-and-forth” syndrome. Players frequently must traverse the entire castle multiple times as new items unlock new areas, a staple of the genre that can induce fatigue.

Pacing and Frustration Management: A critical design choice is the skip button. Most puzzles can be skipped after a short wait (around 30 seconds). This is a double-edged sword. It makes the game accessible to all skill levels and prevents frustrating roadblocks, as praised by the JayisGames reviewer. However, it also undermines the puzzle integrity; a player can simply skip the more challenging logic puzzles, reducing them to speed bumps rather than meaningful obstacles. The game’s length (2-3 hours for most players) is directly tied to this accessibility but is its most common point of criticism.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Handsome, Haunting Shell

Visual Direction and Atmosphere: The game’s strongest suit is its art. The castle of Orion is rendered in a detailed, illustrative style with a muted, earthy palette that conveys age and melancholy. Each room has a distinct identity: the grand but crumbling Throne Room, the weapon-filled Armory, the delicate Princess’s Chamber, the earthy Crypt. The “petrified” inhabitants are statuesque and often placed in dramatic poses, creating powerful tableaus that hint at the moment of the curse. The use of lighting—torchlight, dim corridors, garden sunshine—adds atmosphere. The “sparkling” HOS indicators are integrated subtly into the environment (dust motes, glints of light), which is a nice touch.

Sound Design and Music: The soundtrack is atmospheric and suitably haunting, using string instruments and minimal percussion to maintain a somber, mysterious tone. It loops without becoming overly repetitive. The sound effects for interactions (clinking metal, rustling parchment, a match striking) are clear and functional. However, as noted, the voice acting is a significant weak point. The performances are flat and often awkward, with questionable accent choices and a lack of emotional nuance. This is particularly detrimental during the few narrative cutscenes, where the amateur delivery undercuts the intended drama.

Cohesion and Thematic Resonance: The world-building is surface-level effective. The castle feels lived-in (albeit frozen), with clues like tablets with elemental sayings (“Water defeats Fire,” “Fire destroys Metal”) that foreshadow the final elemental puzzle sequence. This creates a nice sense of environmental storytelling—the player is a detective piecing together the kingdom’s last moments from scattered writings. However, the thematic depth stops there. The elemental theme is purely mechanical for the final puzzle; the “witch” antagonist is a name dropped in the last minutes, with no personality or presence. The world is a beautifully decorated stage set with little behind the scenery.

Reception & Legacy: A Solid Start, an Incomplete Story

Critical and Commercial Reception: The game received a lukewarm critical reception, exemplified by the single aggregated critic score of 60% on MobyGames (from GameZebo). The consensus from that review is telling: “Fun and fair hidden object scenes. Challenging contextual puzzles. Good art design. Interesting whodunit story.” But it is immediately followed by the damning cons: “Amateur voice acting. Dissatisfying cliffhanger ending. Much, much too short.” Player ratings on MobyGames (3.8/5 from 4 votes) and JayisGames (4.4/5 from 48 votes) are slightly higher, suggesting casual players were more forgiving of its brevity and forgiving of its simplicity, appreciating its aesthetics and accessible design.

Industry Influence and Series Legacy: Royal House of Stone did not revolutionize the HOG genre. Its influence is in its template consolidation. It refined a model: 1) A single, connected fantasy setting. 2) A journal for lore and hints. 3) A mirror hint system that doubled as an environmental object. 4) Elemental or thematic puzzle progression. 5) A “save the petrified people” narrative structure. This template was exported directly into its sequels and countless other HOGs. Orneon went on to produce five more titles in the Echoes of the Past series (The Castle of Shadows, The Citadels of Time, The Revenge of the Witch, The Kingdom of Despair, Wolf Healer), each iterating on this formula with new elemental themes, locations, and minor mechanics. The series ran until at least 2015, indicating commercial success for Big Fish, but none of the sequels achieved breakout status. The game is also included in bundles like the Murder, Mystery & Mirrors Triple Pack and the Echoes of the Past Bundle, cementing its role as a catalog title for casual game distributors.

Its legacy is that of a competent foundational work. It proved that a small studio could produce a visually appealing, mechanics-sound HOG that could sit comfortably alongside bigger names. However, its short length and unresolved story made it a cautionary tale about the risks of episodic design in a premium download market. Players felt they had purchased half a product.

Conclusion: A Charming but Ephemeral Artifact

Echoes of the Past: Royal House of Stone is a game out of time. It is a perfect snapshot of the casual game gold rush at its most formulaic yet sincere. Its strengths—attractive, coherent art direction; a generally fair and logical puzzle design (with clever exceptions like the weight and paint puzzles); an accessible, low-friction interface—are exactly what the target audience of 2009-2010 desired. Its weaknesses—abysmal voice acting, a story that is more prologue than narrative, and a runtime that feels like a demo for a fuller experience—are the endemic flaws of a genre often built on volume over depth.

In the grand history of video games, Royal House of Stone is a footnote. It did not pioneer a genre, redefine interactivity, or tell a story that resonated beyond its playtime. However, within the specific ecosystem of casual adventure games, it represents a well-executed早期 iteration of a now-standard template. It is the kind of game that, for two hours, can transport you to a nicely rendered, quietly melancholic castle and engage your logic without undue stress. It is perfectly forgettable, yet in its moment, perfectly pleasant. For historians, it is valuable as a data point: proof that the “hidden object + puzzle adventure” hybrid had, by 2009, become a reliably engineered experience, polished to a sheen but often hollow at its core. Its true verdict is not whether it is a “good” game by the standards of narrative-driven RPGs or action epics, but whether it succeeds at its intended purpose as a casual mindfulness exercise. By that modest measure, it is, like its petrified characters, frozen in a state of qualified success—beautiful to look at, but ultimately waiting for a more potent spell to bring it fully to life.