- Release Year: 1983

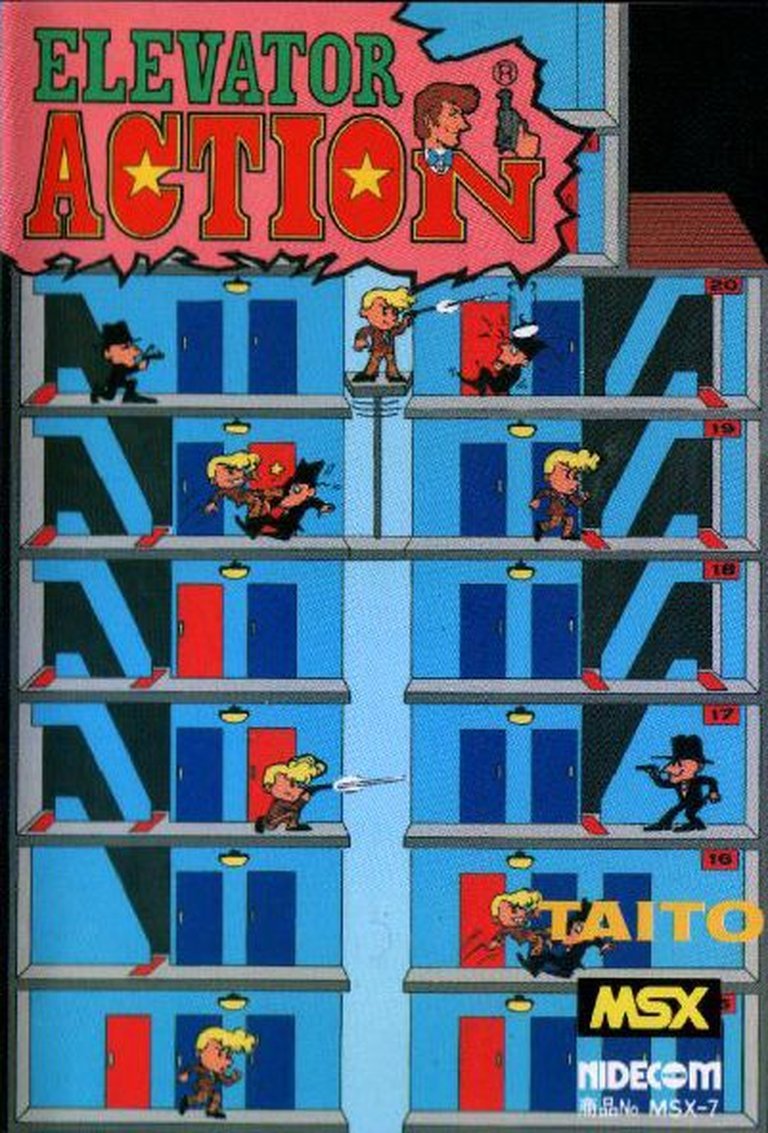

- Platforms: Amstrad CPC, Antstream, Arcade, Atari 2600, Commodore 64, FM-7, Game Boy, J2ME, MSX, NES, Nintendo 3DS, Nintendo Switch, PC-88, PlayStation 4, SG-1000, Sharp X1, Wii U, Wii, Windows, ZX Spectrum

- Publisher: Bug-Byte Software Ltd., CGE Services Corporation, Hamster Corporation, MediaKite Distribution Inc., Nidecom Soft, Quicksilva Ltd., SEGA Enterprises Ltd., Square Enix Co., Ltd., Taito America Corporation, Taito Corporation

- Developer: Taito Corporation

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Platform, Shooter, Stealth

- Setting: espionage, Spy

- Average Score: 60/100

Description

In ‘Elevator Action’, you play as Agent 17, codenamed ‘Otto’, a spy tasked with infiltrating a 30-floor building to retrieve top-secret documents and escape via a getaway car in the basement. The game is set in a high-stakes espionage environment where enemy spies lurk on every floor, ready to eliminate you. You must navigate through the building using elevators and escalators, collecting documents from red-doored rooms while avoiding or eliminating enemies by shooting, kicking, or using environmental traps like dropping ceiling lights or crushing foes with elevators. The challenge escalates as time runs out, triggering alarms that make elevators sluggish and enemies more aggressive, adding urgency and difficulty to your mission.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Elevator Action

Elevator Action Free Download

Elevator Action Guides & Walkthroughs

Elevator Action Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (60/100): A unique blend of platforming, action, and strategy.

olympicelevator.com : A spy-themed arcade classic that turned elevators into strategic gameplay tools.

xander51.medium.com : A design that masterfully blends simple controls and surprising gameplay complexity.

Elevator Action Cheats & Codes

Nintendo Entertainment System (NES)

Enter codes using the Game Genie device.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| GXEUOUVK | Player 1 has infinite lives |

| AAULNLZA | Player 1 starts with 1 life |

| IAULNLZA | Player 1 starts with 6 lives |

| AAULNLZE | Player 1 starts with 9 lives |

| IEVUULZA | Player 2 starts with 6 lives |

| AEVUULZE | Player 2 starts with 9 lives |

| GASTLPTA | Can only shoot one bullet |

| PESIAYLA + NNUSZNSN | Slower man |

| IESIAYLA + XNUSZNSN | Faster man |

| ZAVTLOAE + VYVTYOEY | Faster bullets |

| GAVTLOAA + KYVTYOEN | Slower bullets |

| GEONGPZA + XNXNGOVN | Faster enemy |

| PEONGPZA + NNXNGOVN | Slower enemy |

| 0590:09 | Infinite Lives |

| SXOIYNGK+SZNSNOGK+SZVISXGK+SXNSNXGK+SXSSVKGK+SZSSXSGK+SXOTZEGK | Bullet Invincibility |

| AAKIUILA | Don’t Fall down elevator shafts |

Game Boy (USA, Europe)

Enter codes using the Game Genie device.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 3C8-A8F-7F4 | Don’t Stop Blinking After Taking Damage |

| B65-90F-3BE | Infinite Lives |

| C97-F0F-C49 | Invincibility |

| B68-18F-3BE | Invincible To Enemy Attacks |

| 00C-D1F-E69 | Jump in Mid Air |

| AF4-CBB-7F4 | Otto Does Not Have To Retrieve Disks To Escape |

| 014-F6F-E66 | Start With 1 Life |

| 064-F6F-E66 | Start With 6 Lives |

| 094-F6F-E66 | Start With 9 Lives |

Elevator Action: A Comprehensive Retrospective

Introduction: The Spy Who Loved Elevators

In the pantheon of arcade classics, Elevator Action (1983) stands as a testament to Taito’s ingenuity—a game that transformed the mundane act of riding an elevator into a high-stakes espionage thriller. Released during the golden age of arcade gaming, Elevator Action defied conventions by blending platforming, stealth, and action into a cohesive, addictive experience. Its premise was deceptively simple: infiltrate a 30-story building, collect classified documents, and escape via a getaway car in the basement. Yet, beneath this straightforward objective lay a masterclass in game design, where elevators were not merely set dressing but the very heart of the gameplay.

This review will dissect Elevator Action in exhaustive detail, exploring its development history, narrative subtleties, mechanical brilliance, and enduring legacy. We will argue that Elevator Action was not just a product of its time but a visionary title that influenced generations of games, from Metal Gear to Hitman, by proving that environmental interaction and strategic depth could thrive in an arcade setting.

Development History & Context: Taito’s Vertical Ambition

The Studio and the Vision

Taito, founded in 1953 as a vending machine company, pivoted to video games in the late 1970s, quickly establishing itself as a powerhouse with titles like Space Invaders (1978). By 1983, the arcade landscape was dominated by shoot-’em-ups and high-score chasers, but Taito sought to innovate. Elevator Action was conceived by designer Toshio Kono, who envisioned a game where verticality and environmental interaction were central to the experience. The game ran on the Taito SJ System, a hardware platform shared with other classics like Jungle Hunt and Zoo Keeper, but it was the software that set Elevator Action apart.

The game’s development coincided with a shift in arcade culture. Players were no longer satisfied with mere reflex tests; they craved games with depth, strategy, and a semblance of narrative. Elevator Action delivered on all fronts, offering a spy-themed adventure where players could manipulate their surroundings—shooting out lights, crushing enemies with elevators, and outmaneuvering foes in a labyrinthine skyscraper.

Technological Constraints and Innovations

The early 1980s posed significant technical limitations. Memory was scarce, and graphics were rudimentary by modern standards. Yet, Elevator Action leveraged these constraints to its advantage. The 2D side-scrolling perspective, while simple, allowed for precise platforming and elevator mechanics. The game’s use of color—particularly the stark contrast between the red document doors and the blue enemy doors—created an intuitive visual language that guided players without text.

One of the game’s most innovative features was its dynamic lighting system. Shooting a ceiling light would plunge the floor into darkness, temporarily blinding enemies and adding a layer of stealth. This mechanic was not just a gimmick; it was a strategic tool that rewarded players for creative thinking. Similarly, the elevators themselves were a marvel of design. Players could ride inside them, control their movement, or even perch atop them—though the latter left them vulnerable to enemy fire.

The Gaming Landscape of 1983

Elevator Action debuted in a crowded arcade scene. Competitors like Donkey Kong (1981) and Pac-Man (1980) had already set the standard for platformers and maze games, while Dragon’s Lair (1983) wowed audiences with its laserdisc graphics. Yet, Elevator Action carved its niche by focusing on gameplay depth over visual spectacle. It was a game that demanded both quick reflexes and tactical planning, a rarity in an era where most titles relied on brute-force memorization.

The game’s release was met with enthusiasm. In Japan, it topped the Game Machine charts for three consecutive months (September to November 1983), a feat that cemented its status as a commercial juggernaut. In North America, it was praised for its originality, with Computer and Video Games magazine hailing it as a “pleasant change from the normal space-age shoot-’em-ups.” Its success was further bolstered by Taito’s decision to release it as a conversion kit—a cost-effective way for arcade operators to update their cabinets without purchasing entirely new hardware.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Spy Who Wasn’t There

Plot and Characters: Minimalism as Strength

Elevator Action’s narrative is sparse but effective. Players assume the role of Agent 17, codenamed “Otto,” a lone operative tasked with infiltrating a high-security building to retrieve classified documents. The mission is straightforward: descend from the roof to the basement, collect all documents behind red doors, and escape in a waiting car. There are no cutscenes, no dialogue, and no exposition—just pure, unadulterated gameplay.

This minimalism is not a flaw but a deliberate choice. The absence of a convoluted plot allows the game to focus on its core mechanics, immersing players in the role of a spy through environmental storytelling. The building itself becomes the antagonist, a labyrinth of elevators, escalators, and enemy agents who grow increasingly aggressive as time ticks away. The alarm system, which activates if the player lingers too long, amplifies the tension, transforming the skyscraper into a ticking time bomb.

Themes: Isolation, Precision, and the Illusion of Control

At its heart, Elevator Action is a game about control—or the lack thereof. The player’s ability to manipulate elevators and lights grants a sense of agency, but this control is fragile. Enemies can shoot through elevator doors, lights can be extinguished by foes, and the alarm system can render elevators sluggish and unpredictable. The game’s difficulty curve reinforces this theme: early floors are manageable, but as the player descends, enemies become more aggressive, doors spawn foes more frequently, and the margin for error shrinks.

The game also explores the theme of isolation. Otto is alone in his mission, with no allies or backup. The only interaction comes from the enemy agents, who are faceless and interchangeable, reinforcing the cold, impersonal nature of espionage. Even the getaway car at the end of each level is a solitary escape—no fanfare, no celebration, just the next mission.

Dialogue and Atmosphere: The Sound of Silence

Elevator Action’s sound design is understated but effective. The game’s soundtrack, composed by Yoshio Imamura, consists of a looping, upbeat tune that perfectly complements the game’s frantic pace. The sound effects—gunshots, elevator dings, and the ominous alarm—are minimal but serve their purpose, heightening the tension without overwhelming the player.

The lack of voice acting or dialogue further enhances the game’s atmosphere. The silence of the building, punctuated only by the player’s actions and the occasional enemy gunfire, creates a sense of solitude and focus. It’s a far cry from the bombastic audio of contemporary arcade games, but it suits Elevator Action’s stealthy, methodical gameplay.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Elevator as a Weapon

Core Gameplay Loop: Descend and Survive

Elevator Action’s gameplay is built around a simple but compelling loop: descend the building, collect documents, and escape. Each floor presents a new challenge, with enemies emerging from doors and elevators moving unpredictably. The player must navigate this gauntlet using a combination of shooting, jumping, and elevator manipulation.

The game’s controls are intuitive but precise. Otto can move left and right, jump, duck, and fire his pistol. The elevators, however, are the game’s defining feature. Players can enter an elevator to control its movement, ride on its roof (though this leaves them vulnerable), or even use it to crush enemies. The escalators, while less versatile, provide a quick way to traverse floors without waiting for an elevator.

Combat and Enemy AI: A Dance of Death

Combat in Elevator Action is a delicate balance of aggression and caution. Enemies can be dispatched in several ways:

– Shooting: The most straightforward method, but enemies can duck or lie flat to avoid bullets.

– Jump-Kicking: A close-range attack that rewards precise timing.

– Light Dropping: Shooting a ceiling light not only darkens the floor but can also crush enemies beneath it.

– Elevator Crushing: Luring an enemy beneath an elevator and then moving it downward is both satisfying and strategic.

The enemy AI is simple but effective. Agents emerge from doors, shoot at the player, and occasionally take cover. Their behavior becomes more aggressive as the player progresses, with later floors featuring enemies that lie flat—making them nearly impossible to hit unless the player is in an elevator.

Progression and Difficulty: The Art of the Grind

Elevator Action’s difficulty is notorious. The game starts deceptively easy, but the challenge ramps up quickly. Enemies become faster, elevators grow less responsive, and the alarm system adds a layer of urgency. The game’s scoring system incentivizes risk-taking, with bonuses awarded for collecting documents quickly and dispatching enemies in creative ways.

One of the game’s most frustrating (but brilliant) mechanics is its handling of missed documents. If the player reaches the basement without collecting all the documents, they are teleported back to the highest floor with an unopened red door. This forces players to retrace their steps, often through floors teeming with enemies. It’s a punishing mechanic, but it reinforces the game’s themes of precision and thoroughness.

UI and Feedback: Clarity in Chaos

The game’s UI is minimal but effective. The player’s score, lives, and current floor are displayed at the top of the screen, while the elevator’s position is indicated by a small marker. The red and blue doors are color-coded for easy identification, and the alarm system is signaled by a flashing light and a change in music.

Feedback is immediate and clear. Shooting an enemy yields a satisfying “ping,” while collecting a document triggers a brief animation. The game’s lack of a health bar—players lose a life in one hit—adds to the tension, as every mistake is potentially fatal.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Skyscraper as a Character

Setting and Atmosphere: A Building Full of Secrets

Elevator Action’s setting is its greatest strength. The 30-story building is more than just a backdrop; it’s a living, breathing entity that reacts to the player’s actions. The elevators, escalators, and doors create a dynamic environment where every floor presents new challenges. The game’s verticality is its defining feature, with players constantly moving up and down, never knowing what awaits them on the next floor.

The building’s design is both functional and oppressive. The red doors (containing documents) and blue doors (spawning enemies) create a visual shorthand that guides the player’s progress. The darkened floors, where lights have been shot out, add a layer of unpredictability, forcing players to rely on memory and quick reflexes.

Visual Design: Simplicity as Sophistication

The game’s graphics are a product of their time, but they are also a masterclass in clarity. The sprites are small but distinct, with Otto’s red jacket and the enemies’ black suits creating a clear visual contrast. The elevators are rendered in a bright yellow, making them easy to spot amidst the building’s muted tones.

The game’s use of color is particularly effective. The red doors stand out against the building’s gray and blue palette, drawing the player’s eye and reinforcing their importance. The darkened floors, rendered in a deep blue, create a sense of danger and uncertainty.

Sound Design: The Music of Espionage

Yoshio Imamura’s soundtrack is a perfect match for the game’s frenetic pace. The main theme is a catchy, upbeat tune that loops seamlessly, keeping players engaged without becoming repetitive. The sound effects—gunshots, elevator dings, and the alarm—are minimal but effective, heightening the tension without overwhelming the player.

The game’s audio design is particularly notable for its use of silence. The building is eerily quiet, with only the occasional enemy gunfire or elevator movement breaking the stillness. This creates a sense of isolation and focus, reinforcing the player’s role as a lone operative in a hostile environment.

Reception & Legacy: The Game That Refused to Stay Grounded

Critical and Commercial Reception

Elevator Action was a critical and commercial success upon release. In Japan, it topped the Game Machine charts for three consecutive months, a testament to its popularity. In North America, it was praised for its originality and depth, with Computer and Video Games magazine calling it a “pleasant change from the normal space-age shoot-’em-ups.”

The game’s reception was not universally positive, however. Some critics found the difficulty curve too steep, while others criticized the repetitive level design. The home ports, particularly the NES and Commodore 64 versions, received mixed reviews, with some praising their faithfulness to the arcade original and others lamenting their technical limitations.

Evolution of Reputation

Over time, Elevator Action’s reputation has only grown. Retrospective reviews, such as Eurogamer’s 2007 analysis, have praised the game’s enduring playability and innovative mechanics. The game’s influence can be seen in countless titles, from Metal Gear Solid’s stealth mechanics to Hitman’s emphasis on environmental interaction.

The game’s legacy is also evident in its numerous sequels and re-releases. Elevator Action Returns (1994) expanded on the original’s mechanics with faster-paced gameplay and new weapons, while Elevator Action Deluxe (2011) introduced a quirky, cartoonish art style and multiplayer modes. The game’s inclusion in compilations like Taito Legends and Arcade Archives has ensured that new generations of players can experience its brilliance.

Influence on Subsequent Games

Elevator Action’s impact on the gaming industry cannot be overstated. Its blend of platforming, stealth, and environmental interaction paved the way for countless titles. Games like Rolling Thunder (1986) and Shinobi (1987) borrowed its side-scrolling action and espionage themes, while Metal Gear (1987) expanded on its stealth mechanics.

The game’s use of elevators as a gameplay mechanic has also left a lasting mark. Titles like Impossible Mission (1984) and The Simpsons Arcade Game (1991) featured similar vertical traversal, while modern games like Deus Ex and Dishonored have embraced environmental interaction as a core mechanic.

Conclusion: A Masterpiece of Vertical Design

Elevator Action is more than just a relic of the arcade era; it is a masterpiece of game design that continues to inspire and challenge players decades after its release. Its innovative use of elevators, dynamic lighting, and environmental interaction set a new standard for arcade games, proving that depth and strategy could thrive in a medium often dismissed as shallow.

The game’s legacy is evident in its enduring popularity, its influence on subsequent titles, and its continued relevance in discussions of game design. It is a testament to Taito’s vision and a reminder that even the simplest mechanics—when executed with precision and creativity—can create an experience that transcends its era.

Final Verdict: 9/10 – A Timeless Classic

Elevator Action is not just a great arcade game; it is a landmark title that redefined what an arcade game could be. Its blend of action, strategy, and environmental interaction remains unmatched, and its influence can be felt in countless games that followed. For anyone interested in the history of video games or the art of game design, Elevator Action is essential playing.