- Release Year: 2015

- Platforms: Android, iPad, iPhone, Macintosh, PlayStation 4, Windows, Xbox One

- Publisher: SKH Apps LLC

- Developer: Google Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Survival horror

- Average Score: 71/100

Description

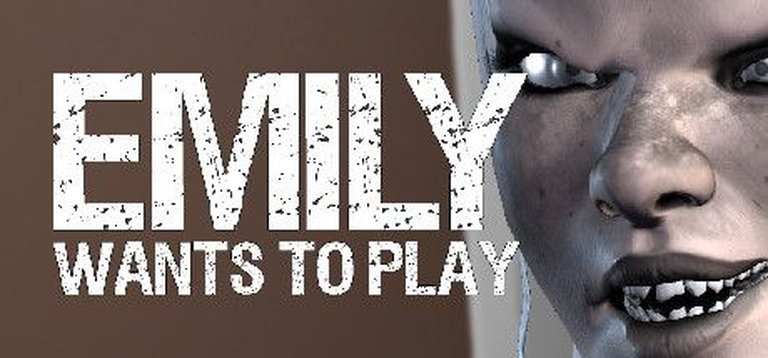

On a rainy night, a pizza delivery person becomes trapped inside a boarded-up, overgrown house at 11 PM until midnight, when increasingly terrifying dolls and characters—starting with Kiki the doll, followed by Mr. Taters the Clown, Chester, and finally Emily herself—appear each hour. This first-person survival horror game challenges players to explore the house, evade hostile entities, and find a way out before dawn.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Emily Wants to Play

Emily Wants to Play Cracks & Fixes

Emily Wants to Play Mods

Emily Wants to Play Guides & Walkthroughs

Emily Wants to Play Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (75/100): Achieves what it sets out to do fantastically – scare the absolute bejesus out of you.

imdb.com (60/100): The game did provide me some jumps though and it did provide me with something to cuss at, so it is okay, just not a lot of replay value once you actually win the game.

gamefaqs.gamespot.com : It’s good for a few genuine scares, and is a fun game to make the easily frightened of your friends and [presumably laugh].

Emily Wants to Play: Review

Introduction

It’s eleven PM. Rain lashes against the boarded-up windows of a dilapidated house on 905 Sister Street, a final delivery looms on the horizon, and the front door creaks open. A pizza delivery man for Checkers Pizza steps inside, seeking shelter from the storm—and stumbles into a nightmare. Emily Wants to Play (2015), the debut from indie developer Shawn Hitchcock, is a masterclass in minimalist horror. Trapped in a house by a ghostly girl and her sentient dolls, players must survive a gauntlet of children’s games warped into lethal trials. This review dissects Hitchcock’s creation, a game that leveraged the indie horror boom of the mid-2010s to craft a uniquely suffocating experience. While its simplicity and reliance on jump scares limit its depth, Emily Wants to Play endures as a cult phenomenon—a testament to how psychological tension and atmosphere can trump graphical fidelity or complex systems.

Development History & Context

Shawn Hitchcock conceived Emily Wants to Play as a solo passion project, inspired by two titans of the genre: P.T.’s oppressive atmosphere and Five Nights at Freddy’s* escalating dread. Announced in September 2015 via Steam Greenlight, the game’s development was swift, leveraging Unreal Engine 4 to render its environments with functional, if basic, 3D graphics. Hitchcock’s vision was unapologetically low-budget: no sprawling levels, no elaborate combat—just a single house, a handful of antagonists, and a relentless focus on survival. This ambition aligned with the era’s indie landscape, where Steam’s digital storefront and platforms like YouTube and Twitch democratized horror. Games like Slender: The Arrival and Outlast had proven that atmospheric, low-budget experiences could capture the zeitgeist, and Emily Wants to Play capitalized on this trend by distilling terror to its essence: isolation, pattern recognition, and the fear of the unknown.

Released on December 10, 2015, for Windows and macOS, the game’s success prompted rapid porting. iOS, Android, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and even Oculus Rift VR versions followed in 2016, demonstrating Hitchcock’s keen understanding of accessibility. The VR iteration, in particular, enhanced the immersion, making the dolls’ jump scares feel intimate and inescapable. By focusing on a single, self-contained narrative, Hitchcock sidestepped the need for sprawling resources, instead channeling energy into refining the game’s core mechanics—a choice that defined its identity in a crowded market.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Emily Wants to Play unfolds through environmental storytelling, its plot pieced together from scattered notes, audio recordings, and news reports. The premise is deceptively simple: a pizza delivery man is trapped in a house by Emily Withers, a deceased girl, and her three dolls—Kiki (a porcelain doll), Mr. Tatters (a clown), and Chester (a ventriloquist dummy). The true horror, however, lies in the backstory. Emily’s mother, Maggie, left behind tapes revealing a tragic spiral: Emily, once a normal child, descended into depression after her family moved to 905 Sister Street. She found solace in the basement dolls, but her parents, fearing her violent outbursts (including killing a puppy), locked her away. When Emily was found dead under mysterious circumstances, the house became a crime scene—her parents murdered by the same entities now tormenting the player.

This narrative layers profound themes. Childhood Innocence Corrupted is central: Emily’s dolls, initially toys, become conduits for a malevolent entity (fan theories posit Vult Ludere, a puppet master from the sequel, as the source). The games the dolls force upon the player—peek-a-boo with Kiki, red light/green light with Mr. Tatters, tag with Chester—twist childhood joy into psychological torture. Equally potent is Tragedy and Abandonment: Emily’s loneliness and her parents’ failure to protect her echo in the house’s desolation. Notes like “They don’t care about me, they never loved me” and “Join Us” scrawled on walls suggest Emily’s spirit seeks companionship in death. The game’s ending, where the police dismiss the protagonist’s claims and the dolls are cataloged as evidence, underscores a Cassandra Truth—the protagonist’s sanity is questioned, leaving the house’s horrors unresolved.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Emily Wants to Play operates on a rigid, hour-by-hour loop, with each segment introducing a new antagonist or escalating threats. At 11 PM, the player explores freely but is warned: descending to the basement before 4 AM results in instant death. By midnight, Kiki emerges, forcing players to engage in a deadly game of peek-a-boo. Her giggle signals proximity; players must stare at her until she vanishes, lest she appear behind them for a jump scare. At 1 AM, Mr. Tatters enforces red light/green light: any movement while he “sees” the player triggers a kill. Chester, at 2 AM, plays tag—running is the only escape, but doors slam shut, creating claustrophobic chase sequences.

The systems deceptively simple: players interact with light switches, read clues, and wield a flashlight. Yet the whiteboard in the kitchen subverts expectations, offering lies (e.g., “Don’t look at Kiki”) mixed with truths (e.g., “I HIDE YOU SEEK IN THE DARK” at 4 AM). This creates a meta-puzzle, forcing players to trust intuition over text. At 4 AM, Emily herself becomes the antagonist, a hide-and-seek game with a countdown timer. By 5 AM, all threats combine, demanding mastery of prior mechanics.

Flaws emerge in the luck-based execution. Random doll spawns sometimes create unfair scenarios (e.g., Chester and Mr. Tatters appearing simultaneously, requiring contradictory actions). The lack of combat or progression systems beyond survival limits replayability, though the 6 AM escape sequence offers catharsis. Still, the escalating tension—from a single doll to a full-scale siege—transforms a short experience into a memorable ordeal.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The house at 905 Sister Street is a character in itself, a decaying vessel of trauma. World-building is meticulous: overgrown lawns, boarded windows, and a gaping basement hole imply neglect and supernatural decay. Each room tells a story—a laptop ordering the pizza, drawings of Emily and the dolls, and Maggie’s tapes. The art direction prioritizes unease over fidelity. Kiki’s black eyes and porcelain skin, Mr. Tatters’ garish clown attire, and Chester’s wooden joints are low-poly but effective. Emily, with her white hair and gaunt figure, evokes classic horror imagery (e.g., The Grudge), while the house’s generic textures (peeling wallpaper, flickering lights) amplify realism.

Sound design is the game’s unsung hero. Kiki’s giggle shifts from playful to menacing, Mr. Tatters’ demonic chuckle punctuates silence, and Chester’s childlike laugh triggers panic. Footsteps echo in hallways, and the thud of a closing door amplifies isolation. The soundtrack is sparse, relying on ambient hums and sudden silences to build dread. This audio-visual synergy makes even mundane actions—turning a light switch, opening a door—tense. The basement, in particular, uses sound to disorient, with distant laughs and clattering dolls ensuring players never feel safe.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Emily Wants to Play polarized critics but found a dedicated audience. Metacritic scored it 75/100 (“generally favorable”), with praise for its atmosphere. GameSpew (76%) lauded its “disconcerting atmosphere,” while Digitally Downloaded (70%) argued it excelled at jump scares but lacked emotional depth. Players on Steam awarded it a “Mostly Positive” 78%, with 2,237 reviews. Critics noted its short runtime (under an hour) and repetitive deaths, but many conceded it delivered on its promise: cheap, effective scares.

Commercially, the game thrived across platforms, proving indie horror’s market viability. Its legacy lies in its influence on the genre. It popularized the “single-location survival” subgenre, inspiring games like Pacify (another Hitchcock title) and Hello Neighbor. The sequel, Emily Wants to Play Too (2017), expanded the lore but retained the core formula. Fan theories, particularly the Vult Ludere hypothesis, kept the community engaged, while the announced Emily Wants to Play 3 promises to close the loop. More than a game, Emily Wants to Play became a cultural touchpoint—perfect for Twitch streamers and Halloween marathons, its scares as reliable as they are relentless.

Conclusion

Emily Wants to Play is a paradox: a game of profound simplicity yet lasting impact. Hitchcock’s creation succeeds not through innovation but through mastery of fundamentals. The escalating tension, the psychological dread of the dolls, and the tragic backstory of Emily coalesce into an experience that lingers long after the credits roll. Its flaws—repetitive gameplay, reliance on luck, and a fleeting runtime—prevent it from being a masterpiece, but they underscore its indie spirit: a labor of love, unburdened by AAA expectations.

In the pantheon of horror games, Emily Wants to Play occupies a unique niche. It is the digital equivalent of a campfire ghost story—short, visceral, and undeniably effective. For players seeking terror distilled to its purest form, it remains essential. As the pizza delivery man’s fate suggests, some games are not meant to be won, but merely survived.