- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Activision Publishing, Inc., ak tronic Software & Services GmbH, Sierra Entertainment, Inc., Sold Out Sales & Marketing Ltd.

- Developer: BreakAway Games Ltd., Impressions Games

- Genre: Simulation, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Business simulation, City building, construction simulation, Managerial

- Setting: Ancient, China, Imperial

Description

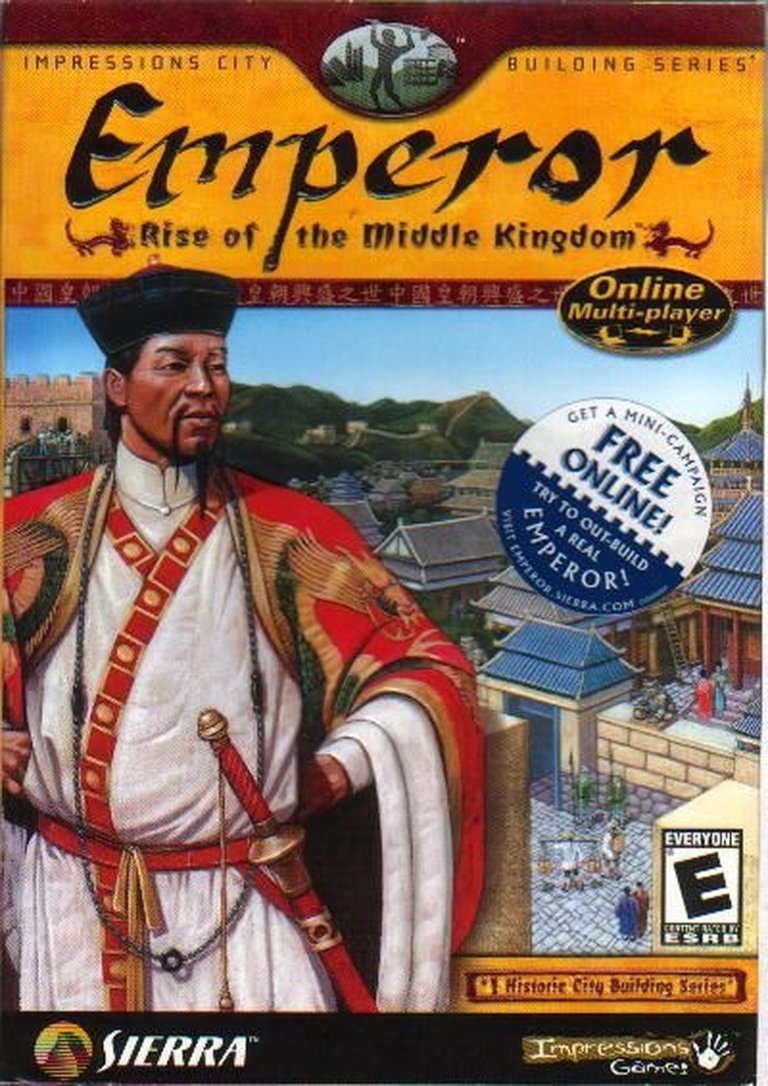

Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom is a city-building strategy game set in ancient China, where players design and manage urban centers across 3000 years of history, navigating the complexities of politics, trade, and diplomacy as dynasties emerge and decline. Drawing inspiration from historical Chinese eras, the gameplay involves constructing cities with balanced access to resources, entertainment, and religious structures, while adapting to economic, military, and diplomatic shifts, akin to other titles in the Impressions City Building Series like Caesar III and Pharaoh, with added multiplayer support and enhanced graphics.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom

PC

Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom Free Download

Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom Patches & Updates

Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom Guides & Walkthroughs

Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom Reviews & Reception

ign.com : But there isn’t really anything here that we haven’t already gone through in ancient Rome, Egypt, or Greece.

gamewatcher.com : Breakaway has managed to keep things according to the true historical facts as much as possible

Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom Cheats & Codes

PC

Press CTRL+ALT+C to bring up the cheat console.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| Bad Wallpaper | All buildings become inauspicious |

| Black Death | Kills all military units |

| CeramicsForElite | All elite houses get 100 ceramics |

| Chinese Flu | One house becomes infected |

| Delian Treasury | Add 5,000 Delians |

| Framerate | Unknown effect |

| Glub Glub | Flood |

| Gimme Goods | Get free goods in warehouse/mill |

| Great Heat | Drought |

| HempForElite | All elite houses get 100 hemp |

| IgnoreDesire | Ignore desirability values in housing evolution |

| I win again | Win mission |

| Jumble town | Unknown effect |

| Kill Enemy Units | Kills all enemy military units |

| Kill Load Units | Kills all load units |

| Kill Loan Units | Kills all loaned military units |

| Lizardman | Hero changes to giant lizard |

| Reset Timing | Unknown effect |

| Shake Shake | Earthquake |

| SilkForElite | All elite houses get 100 silk |

| SoundFrags | Unknown effect |

| SpawnBandit | Spawn one bandit in city |

| SpawnMugger | Spawn one mugger in city |

| TeaForElite | All elite houses get 100 tea |

| TimeBandits | Everything is faster |

| Toggle Alpha | Unknown effect |

| Dump Timing | Unknown effect |

| Uncle Sam | Tax collectors change into Uncle Sam |

| WaresForElite | All elite houses get 100 bronzeware/lacquerware |

| FunForElite | Elite houses evolve without required entertainment |

| Shutime | Add 5000 cash |

Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom: The Celestial Peak of a Formula

Introduction: The Mandate of a Formula

In the golden era of isometric city-builders, few series commanded the same respect as Impressions Games’ City Building saga. From the brick-laying streets of Caesar III to the Nile-dependent sprawl of Pharaoh and the god-touched acropolises of Zeus: Master of Olympus, a potent, intricate template had been established. Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom, released in 2002 and developed by BreakAway Games under the Impressions banner, represents both the zenith and the临界点 of that template. It is a game of breathtaking scope and encyclopedic systemic detail, a masterclass in translating a specific historical and cultural milieu into a compelling gameplay loop. Yet, it also stands as the most explicit admission that the formula had reached its apex—refined to a glorious sheen but palpably running in place. This review argues that Emperor is not a revolutionary leap but a consummate evolutionary one: a game that perfected the “Impressions system” within a stunningly realized ancient Chinese context, offering profound depth at the cost of the series’ creative momentum. Its legacy is that of a magnificent, self-aware capstone—the last great game built on a now-retired engine, and the final, sprawling testament to a design philosophy that would soon be eclipsed.

Development History & Context: A Changing of the Guard

The development of Emperor is a story of transition. Impressions Games, the studio synonymous with the series since Caesar, had been acquired and was winding down. The primary development duties were contracted to BreakAway Games, a studio with experience on the series (having worked on Cleopatra: Queen of the Nile expansion) but now taking the helm for a full, mainline entry. This handoff occurred against the backdrop of a rapidly changing PC strategy landscape in the early 2000s. The real-time strategy (RTS) genre, with its focus on base-building and combat, was dominated by titans like Warcraft III and Age of Empires II. Meanwhile, the pure “god game” and city-building niche was becoming a more rarefied space, with SimCity 4 (2003) representing the high-end simulation frontier and The Settlers series offering a different blend of logistics and combat.

Technologically, Emperor was a bridge. It was the last game in the series to use the venerable 2D-sprite engine first seen in Caesar III, a tool honed over years to create beautiful, painterly isometric cities. The visuals received a notable upgrade, with more detailed building graphics and a vibrant, distinct Asian aesthetic that broke from the Mediterranean holdings of its predecessors. However, the underlying architecture was clearly aging. The most significant new technical feature was not graphical but systemic: multiplayer support. For the first time in the series, up to eight players could compete or cooperate over LAN or internet, a forward-looking addition that acknowledged the social turn in PC gaming, even if its implementation was often cumbersome and prone to the infamous AI “cheating” that plagued the series.

BreakAway’s challenge was immense: to take a beloved, thoroughly explored formula and make it feel fresh through a complete thematic reskin. They leaned heavily into historical and cultural research, aiming to make the Chinese setting not just cosmetic but integral to the experience. The vision was to immerse players in 3,000 years of Chinese history, from the semi-legendary Xia dynasty to the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, with all the technological, religious, and social evolutions that entailed. The goal was authenticity through mechanics, a goal that yielded both brilliant successes and notable anachronisms.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Dynasties, Deities, and Disconnect

Emperor’s narrative is delivered through a series of seven historical campaigns, containing nearly 50 missions. This structure is both its greatest narrative strength and its most glaring weakness. The strength lies in its breathtaking chronological sweep. Players journey from establishing a nomadic settlement along the Yangtze in the Xia era, through the Shang’s bronze-wielding might, the philosophical ferment of the Zhou, the tyrannical unification of the Qin, the cosmopolitan Han golden age, the Buddhist Sui/Tang renaissance, and finally the desperate, Mongol-besieged Song/Jin. Each campaign feels distinct, with specific historical figures (like the First Emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi) or events (the construction of the Grand Canal, the defense against Genghis Khan) as backdrops.

The narrative is presented through a third-person omniscient narrator who sets the scene for each mission. This voice is consistently formal, grand, and steeped in the “Mandate of Heaven” philosophy. It praises the current dynasty’s virtue and laments the corruption of its predecessors—only to, in the very next mission or campaign, viciously condemn the now-deposed former rulers. This creates a deliciously ironic, almost satirical through-line that mirrors the cyclical nature of Chinese history: every dynasty’s fall is preceded by a narrative of its decadence, regardless of the player’s own city-building prowess. The final mission of each campaign is a “Downer Ending”—a historical fait accompli. You could build the most resplendent capital of the Qin, but the next Han mission briefing will casually note the dynasty’s collapse and your character’s unlikely survival due to “recognized skill and integrity.” This “Shoot the Shaggy Dog” ending reinforces the player’s role as a permanent, immortal city administrator, a servant of the state that transcends dynasties, and underscores the game’s theme of human endeavor versus the tides of history.

Thematically, the game weaves in three core “Ancestor Gods”—Nu Wa, Shen Nong, and Huang Di—who must be appeased with sacrifices or risk divine wrath in the form of floods, earthquakes, and famines. This system is a direct analogue to the pantheons of Pharaoh and Zeus, but with a distinctly Chinese philosophical bent. Alongside them are Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist heroes (like Sun Tzu, Guan Yu, or Kuan Yin) who offer more specific, utilitarian blessings. The interplay creates a religious ecosystem where the “gods” are more impersonal forces of nature and state, while the “heroes” are culturally specific figures who can be directly petitioned for favors like faster monument construction or free emissaries.

However, the narrative and themes are frequently undermined by Gameplay and Story Segregation. The most egregious example is the “Always Chaotic Evil” portrayal of the northern nomads (Xiongnu, eventually Mongols). They are a monolithic, eternally hostile “barbarian” threat, a crude simplification that erases the complex, often tributary, relationships between Chinese dynasties and steppe peoples. Furthermore, the “Written by the Winners” trope is played for laughs: the narrator will seamlessly switch from extolling the virtues of a dynasty to denouncing it as tyrannical once it falls. The historical inaccuracies are a mixed bag. Some are clever integrations of game mechanics (e.g., the elite housing/military system, a carry-over from Zeus, falsely mirrors a Bronze Age Greek model in a Chinese setting). Others are blatant anachronisms, most notably the Tai Chi parks, which are a 19th/20th-century concept shoehorned into every era. The game’s attempt at “Shown Their Work” is commendable—the chronological appearance of commodities like tea, paper, and iron, the rough accuracy of monument projects—but it is consistently hamstrung by the need to service a pre-existing, culturally-agnostic gameplay engine.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Impressions Engine Perfected

At its core, Emperor is a real-time city-builder with heavy managerial simulation. The primary loop is a constant, delicate balancing act: feed your people, supply their desires, maintain infrastructure, generate wealth, and defend your city. The genius of the Impressions system, refined here, is its walker-based service delivery. You do not directly assign citizens to jobs. Instead, you build a structure (a mill, a herbalist, a temple), which spawns a “walker” who emerges and patrols the adjacent roads, automatically servicing any houses they pass. This creates a systemic, emergent geography where optimal road layouts—often grand, encircling loops for residential districts—are critical to ensure even coverage.

The resource and production chains are exceptionally deep. Food is not a monolith; it’s a portfolio. You must produce a mix of staples (millet, rice, wheat) and luxuries (meat, fish, tofu) to raise food quality. Salt counts as food. Spices and tea are后期 top-tier necessities for luxury housing. Each commodity requires a raw material supply chain: bronzeware needs clay and bronze; lacquerware needs lacquer and wood; paper needs wood pulp. Managing these chains—ensuring your clay pit is staffed, your bronzesmith has material, your warehouse walker distributes the finished goods—is the game’s central intellectual challenge.

The Feng Shui system is Emperor’s signature mechanical innovation. Every building has an elemental affinity (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water). Every terrain tile is also elemental. Placing a building on a harmoniously aligned terrain tile boosts its effectiveness and your city’s overall Approval rating. Conversely, poor placement causes “Family Shamed,” “City Shamed,” and eventually “China Shamed” penalties. This transforms city planning from a simple zoning exercise into a puzzle of elemental harmony. As TV Tropes notes, clever players can exploit the system: build a building on a good spot, then remove the terrain feature (like a tree) to change the elemental makeup, freeing that prime location for another structure. It ties gameplay directly into a core Chinese philosophical concept, making aesthetic and spiritual balance a tangible, mechanical concern.

Combat remains a secondary, though significantly expanded, pillar. Armies are raised from elite housing, a controversial carry-over from Zeus. Each “fort” you build houses a company of soldiers ( Infantry, Crossbowmen, Cavalry, Chariots, Catapults), each with distinct stats and roles—a clear Competitive Balance of Mighty Glaciers, Glass Cannons, and Lightning Bruisers. Conquering a city requires sending an army to its gates, then fighting a real-time tactical skirmish within its walls. The introduction of catapults is crucial for breaching fortifications. However, the AI exhibits classic “Computer Is a Cheating Bastard” tendencies, spawning invaders at random points, and “Artificial Stupidity” in its walkers is legendary—deliverymen will flood one warehouse while ignoring another, and peddlers wander aimlessly unless herded by roadblocks and gates (a new feature allowing selective walker control).

The multiplayer mode was a bold experiment. It allowed competitive races to score points or cooperative efforts to build the Great Wall. While conceptually thrilling for the genre, in practice it was often marred by imbalance and instability. The same underlying engine that made single-player campaigns rich could not handle the dynamic diplomacy and espionage of multiple human empires elegantly. The server shutdown in 2008 rendered it a historical footnote.

The game’s greatest mechanical stride is also its most subtle: the elimination of employment walkers. In Pharaoh and Zeus, industries needed walkers to visit houses to recruit workers, forcing you to mix residential and industrial zones. Emperor made employment automatic and city-wide. As critics noted, this vastly simplifies city planning, eradicating “slums” and allowing for perfect aesthetic separation of dirty industry from pristine elite enclaves via residential walls. This is a profound quality-of-life improvement that makes the game more accessible and the cities more visually coherent, but it also abstracts away a layer of gritty, realistic urban tension.

Reception & Legacy: A Refined, Yet Stagnant, Masterpiece

Emperor was released to generally favorable reviews, with a Metacritic score of 77/100 and an average critic score of 78% on MobyGames. The reception was consistent: praise for its depth, atmosphere, and faithful expansion of the formula, coupled with a near-universal critique of its lack of innovation.

The positive reception focused on its unparalleled scope and immersion. GameZone‘s 93% review hailed its “gorgeous graphics, compelling gameplay, and challenging city management.” IGN (88%), while noting its similarity to predecessors, admitted “it’s a great game” and that the Chinese setting was “perfect” for the genre. Computer Bild Spiele (85%) praised its “unbelievably complex” economic system that felt “taken right out of life.” The multiplayer was singled out as a genuinely new, if flawed, addition by outlets like GameWatcher and PC Zone, which celebrated the “up to eight players” competing to “out-build each other.”

The critical pans were uniformly about stagnation. GameSpot (77%) delivered the most cited verdict: “If Zeus was two steps forward for the series, Emperor is its one step back.” PC Gamer (72%) bluntly stated it “feels as comfortable as a new pair of shoes” for veterans but noted that “several questionable aspects of the series’ general design remain problems.” Gamesmania.de (70%) dismissed it as playing “in the second Bundesliga” compared to the innovation promised by Anno 1503. The sentiment was clear: this was a masterful refinement, not a revolution.

Commercially, it performed solidly within its niche but did not break out. Its legacy is complex:

1. The Swan Song of an Engine: It was the last major title to use the Caesar III engine, a technology pushed to its absolute limits with larger maps and more sprites.

2. A Bridge to the Future: Its direct successor, Caesar IV (2006), moved to a 3D engine but was critically and commercially less successful, often cited as losing the charm of the 2D titles. Emperor now stands as the final, perfected expression of the classic 2D City Building style.

3. Cult Endurance: It developed a dedicated modding community (evidenced by patches like the “EmperorLimitPatch” on ModDB) and remains a beloved, if dated, experience on platforms like GOG.com. Its complex, systemic depth is still admired by hardcore simulation fans.

4. Influence: Its specific mechanics—Feng Shui, the walker-based service model, the deep commodity chains—directly informed later spiritual successors and inspired modern city-builders like Nebuchadnezzar and Against the Storm, which echo its focus on interconnected logistics. However, the series’ core “walkers patrolling roads” model was gradually abandoned by the industry in favor of zoned, radius-based service, seen in SimCity 4 and later titles.

Conclusion: A Lasting, Limiting Greatness

Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom is a game of magnificent contradictions. It is a sprawling, thousand-year epic that feels curiously static. It is a profoundly deep economic simulator that holds its players’ hands with improved interfaces. It transports you to the heart of ancient Chinese cosmology and geopolitics, only to have you conquer the Mongols by bribing them with silk and tea. Its systemic mastery is undeniable, its atmosphere intoxicating, its challenge—once understood—immensely satisfying. Yet, it cannot escape the gravitational pull of its own inheritance.

This is not a failing unique to Emperor; it is the fate of any sequel to a perfected formula. BreakAway Games and Impressions succeeded too well. They polished the Caesar III engine to a mirror sheen, layered in a breathtaking historical layer, and added meaningful (if imperfect) new systems like multiplayer and Feng Shui. The result is a game that, for any newcomer to the genre or devotee of Chinese history, is an absolute masterpiece of design. For the veteran of Pharaoh and Zeus, it is a glorious, familiar, and increasingly predictable homecoming.

Its place in history is secure, if not as a revolutionary landmark then as the definitive conclusion of a classic era. It represents the point where the “Impressions City Builder” became a complete, self-contained thing—exquisitely balanced, culturally distinctive, but creatively exhausted. The step forward would require abandoning its isometric heart and walker soul, a leap that Caesar IV failed to make convincingly. Therefore, Emperor endures not as a beginning, but as a splendid, self-aware ending: the last, greatest emperor of a beloved, fallen dynasty. It is a game that understands its own mandate has been fulfilled, and in that understanding, finds a quiet, enduring majesty.