- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

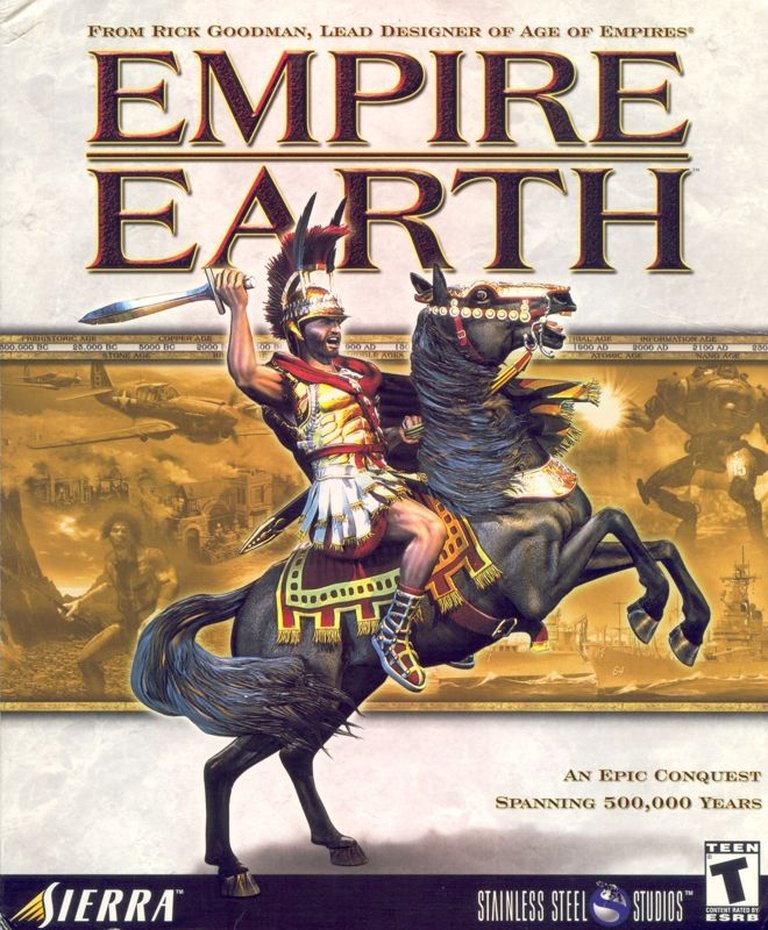

- Publisher: Mastertronic Games Ltd., Novitas Publishing GmbH, Sierra On-Line, Inc.

- Developer: Stainless Steel Studios Inc.

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Base building, Epoch Progression, Real-time combat, Resource Management, Unit recruitment

- Setting: Alternate history, Futuristic, Historical events, Sci-fi, World War I, World War II

- Average Score: 82/100

Description

Empire Earth is a comprehensive real-time strategy game that spans 500,000 years of human history, from the Prehistoric Era to the futuristic Nano Age. Players lead civilizations through four scripted campaigns—including ancient Greece, medieval England, alternate World Wars, and a 2025 Russian empire—or engage in skirmishes and multiplayer battles across 14 epochs, building settlements, managing resources, and waging war with evolving units in settings that blend historical events, alternate timelines, and sci-fi scenarios.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Empire Earth

PC

Empire Earth Free Download

Empire Earth Cracks & Fixes

Empire Earth Patches & Updates

Empire Earth Mods

Empire Earth Guides & Walkthroughs

Empire Earth Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (81/100): What impresses us the most is the sheer size of it — each epoch feels fleshed out and playable, and every era has its own nuances, so it’s almost like getting 14 games in one.

imdb.com (80/100): Empire Earth has all the elements you need in a good strategy game.

gamesreviews2010.com (85/100): Empire Earth is a truly epic RTS game that takes you on a journey through history.

Empire Earth Cheats & Codes

Empire Earth (PC)

Select ‘Random Map’ mode, then enable the ‘Cheat Codes’ option at the setup screen. While playing a game, press [Enter], type the code, then press [Enter] again.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| all your base are belong to us | Gives 100,000 of each resource. |

| atm | Gives 1000 Gold. |

| asus drivers | Removes fog of war, allowing you to see anywhere on the map. |

| bam | Reveal entire map and remove fog of war. |

| boston food sucks | Gives 1000 Food. |

| boston rent | Loses all Gold. |

| brainstorm | Allows instant building and training/creation. |

| coffee train | Heals all units and completes buildings in construction. |

| columbus | Allows you to see Wild Animals. |

| creatine | Gives 1000 Iron. |

| display cheats | Displays all cheat codes. |

| friendly skies | Planes refuel in the air. |

| girlyman | Loses all Iron. |

| headshot | Removes all objects from the map. |

| i have the power | Restores power/mana to mechs, cybers, priests, prophets and strategist heroes. |

| mine your own business | Loses all Stone. |

| my name is methos | Gives 100,000 of all resources, removes fog of war, fully upgrades all available units, allows instant build and max population. |

| rock&roll | Gives 1000 Stone. |

| slimfast | Loses all Food. |

| somebody set up us the bomb | Wins the game. |

| the big dig | Removes all stockpiled resources. No resources |

| the quotable patella | Level 10 upgrade for all units. |

| uh, smoke? | Loses all Wood. |

| you said wood | Gives 1000 Wood. |

| ahhhcool | Loses the game. |

Empire Earth: The Art of Conquest (PC)

Select ‘Random Map’ mode, then enable the ‘Cheat Codes’ option at the setup screen. While playing a game, press [Enter], type the code, then press [Enter] again.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| all your base are belong to us | Gives 100,000 of each resource. |

| atm | Gives 1000 Gold. |

| asus drivers | Removes fog of war, allowing you to see anywhere on the map. |

| bam | Reveal entire map and remove fog of war. |

| bam # (2-15) | Set Age to desired number e.g. bam 15 for Space Age. |

| boston food sucks | Gives 1000 Food. |

| boston rent | Loses all Gold. |

| brainstorm | Allows instant building and training/creation. |

| coffee train | Heals all units and completes buildings in construction. |

| columbus | Allows you to see Wild Animals. |

| creatine | Gives 1000 Iron. |

| display cheats | Displays all cheat codes. |

| friendly skies | Planes refuel in the air. |

| girlyman | Loses all Iron. |

| headshot | Removes all objects from the map. |

| i have the power | Restores power/mana to mechs, cybers, priests, prophets and strategist heroes. |

| mine your own business | Loses all Stone. |

| my name is methos | Gives 100,000 of all resources, removes fog of war, fully upgrades all available units, allows instant build and max population. |

| rock&roll | Gives 1000 Stone. |

| slimfast | Loses all Food. |

| somebody set up us the bomb | Wins the game. |

| the big dig | Removes all stockpiled resources. No resources |

| the quotable patella | Level 10 upgrade for all units. |

| uh, smoke? | Loses all Wood. |

| you said wood | Gives 1000 Wood. |

| ahhhcool | Loses the game. |

Empire Earth: Review

Introduction: The Ambitious Behemoth of Historical RTS

In the crowded pantheon of early 2000s real-time strategy games, Empire Earth dared to ask a question of titanic scale: “What if one game could span the entirety of human conflict, from the first rock thrown in the Pleistocene to the laser fire of the Nano Age?” Released in November 2001 by Stainless Steel Studios, a company founded by Age of Empires lead designer Rick Goodman, Empire Earth was not merely another entry in the RTS boom; it was aShot at a definitive historical sandbox. Its advertised 500,000-year timeline was a direct, audacious challenge to the more focused historical narratives of its contemporaries. This review will argue that Empire Earth is a game of profound, albeit flawed, ambition—a title that succeeds precisely because of its overwhelming scope and willingness to experiment, even when its execution falters under the weight of its own grand design. It stands as a cult classic not in spite of its quirks and difficulties, but because of the unique, “everything and the kitchen sink” experience they create.

Development History & Context: From AoE’s Shadow to a 3D Legacy

Empire Earth was born from the foundational success of Age of Empires. Rick Goodman’s departure from Ensemble Studios to form Stainless Steel Studios was the industry’s signal that a more expansive vision was coming. Announced in May 1998 and showcased at E3 2000 and 2001, the game’s development was a statement of intent. The technological context was the tail end of the DirectX 7/Windows 98/ME era, a period where 3D acceleration was becoming standard but before the widespread adoption of shader models that would define later graphics. The Titan engine, therefore, represented a significant leap into 3D environments from the 2D sprites of Age of Empires II, allowing for features like free camera rotation and zooming, albeit with models that critics and players often found “ugly” or lacking in polish compared to the art of its inspiration.

The gaming landscape of 2001 was fiercely competitive. Blizzard’s Warcraft III and Ensemble’s own Age of Mythology were on the horizon, pushing narrative and hero-centric gameplay. Into this arena, Empire Earth entered with a different proposition: sheer, unadulterated breadth. Its development team, many poached from or sharing history with the Age of Empires team, aimed to perfect a familiar economic and military model while scaling it to an unprecedented historical range. The result was a game that felt immediately familiar to RTS veterans but presented a learning curve as steep as its technology tree due to the sheer volume of epochs, units, and resources.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Scripted History and Alternate Fates

Where Empire Earth’s narrative ambitions truly shine is in its single-player campaigns, which structure its 500,000-year scope into digestible, story-driven sagas. These campaigns are less about开放式 sandbox play and more about curated, cinematic historical vignettes.

The Greek Campaign (8 scenarios) is a masterclass in weaving mythological tone with historical conquest. It begins not with Homer’s epics but with the early Helladic peoples, progresses through the Trojan War (complete with a divinely delivered Trojan Horse), the unification of Attica, the Peloponnesian War, and culminates in Alexander the Great’s epic march to the Persian Gates. The blend of myth and history creates a heroic, almost legendary atmosphere, fitting for the era.

The English Campaign (7 scenarios) presents a nationalistic arc from the Norman Conquest (William the Conqueror at Hastings) through the Hundred Years’ War (the Black Prince, Agincourt) to the Napoleonic Wars (Waterloo). Its strength lies in connecting disparate centuries into a single civilizational narrative. The inclusion of Shakespearean-inspired scenes for Henry V adds a literary layer, though some players found the heavy scripting restrictive, limiting tactical freedom for the sake of plot points like escorting a specific unit through ambushes.

The German Campaign (7 scenarios) is the most controversial, pivoting from the historical (WWI’s Red Baron, Verdun, the Kaiser’s Spring Offensive) to a stark alternate history. The final mission, “Operation Sealion,” tasks the player with a successful Nazi invasion of Britain, culminating in a confrontation with the U.S. 5th Fleet. This unflinching, speculative portrayal of Axis victory is a bold thematic choice, exploring a dark “what if” without explicit narrative judgment, leaving the moral weight to the player.

The Russian Campaign (7 scenarios) is the most audacious, leaping from Ivan the Terrible through WWII and into a sci-fi dystopia. It follows the rise of “Novaya Russia,” a totalitarian state conquering Eurasia, led by the cyborg Grigor Stoyanovich and his successor Grigor II. The plot involves time travel, nuclear threats, and a rebellion led by General Molotov, weaving Cold War paranoia with cyberpunk tropes. This campaign is a jarring but creative leap, using the game’s futuristic epochs (Digital, Nano Age) not as abstract endpoints but as integral parts of a geopolitical thriller.

The expansion, The Art of Conquest, adds the Roman Campaign (a fictionalized account of Caesar’s rise) and the Pacific Campaign (a linear U.S. island-hopping narrative in WWII), further filling out historical gaps. Themes across campaigns include the cyclical nature of warfare, the evolution of technology as the primary driver of conflict, and the blurred line between legendary heroism and brutal conquest. The heavy scripting, while criticized for reducing player agency, creates a cohesive, almost filmic experience that makes each epoch feel narratively significant rather than just a tech tier.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Depth, Density, and Disruption

At its core, Empire Earth uses a time-tested RTS loop: gather resources (Food, Wood, Stone, Gold, and later Iron), build a base, produce military units, and destroy the enemy. Its genius and frustration lie in the scale and complexity applied to this loop.

-

The Epoch System: The 14 (15 with expansion) epochs are the game’s defining feature. Advancing requires building prerequisite structures and paying escalating resource costs, forcing a strategic balance between economy and military. The leap from, say, the Gunpowder Age to the Industrial Age feels genuinely transformative, introducing tanks and aircraft that render prior units largely obsolete. However, this system is a double-edged sword. As player reviews consistently note, the progression between epochs can feel “sketchy” and too fast, especially in multiplayer. The “age race” phenomenon, where players rush to the next epoch as soon as prerequisites are met, can lead to lopsided battles where one advanced force obliterates a larger but outdated one. This undermines the potential for rich, multi-era tactical warfare within a single game, making most matches a sprint to a specific technological sweet spot (often WWI/WWII or Modern) rather than a true marathon through history.

-

Morale, Heroes, and Custom Civs: Empire Earth innovated with a morale system. Units inspired by nearby Town Centers, Houses, or Warrior Heroes gain combat bonuses. Conversely, Strategist Heroes (like Alexander or Churchill) can demoralize enemies and heal allies. This adds a crucial layer of positioning and hero management, though players noted hero abilities often require manual triggering, unlike the automatic auras in Warcraft III. The civilization customization system is another standout. Instead of rigid, asymmetrical factions like in StarCraft, players spend 100 points on unique bonuses (e.g., +20% Tank Attack, +30% Villager Speed). This allows for incredible build diversity and personalized playstyles in multiplayer, though it also means no civilization has a fixed, historically-rooted identity in terms of unique units.

-

The Economy and Unit Design: The five-resource system (with a hard cap of six gatherers per resource patch) encourages focused economic planning. The fixed isometric camera and simple unit controls keep the game accessible, but also limit tactical finesse. The unit counter system is a classic rock-paper-scissors (e.g., Infantry > Cavalry > Archers > Infantry), but it becomes immensely complex with 200+ unit types across epochs. Player reviews highlight both the joy of discovering these interactions (“Tanks countered by Anti-Tank, which are countered by Infantry”) and the frustration of imbalances, such as the dominance of bomber swarms in the Modern Age or the perceived uselessness of the prehistoric era’s limited unit roster.

-

The Infamous AI: The single-player AI is Empire Earth‘s most criticized element. It is widely reported to cheat blatantly, receiving free resources and relentless production regardless of player actions. On higher difficulties, it can field overwhelming forces at a speed no human can match, leading to scenarios where players must build massive, multi-layered walled fortresses (à la Attack on Titan) to survive the initial minutes. This “unfair” AI, while a flaw in balanced play, became a bizarre point of pride for some masochistic players seeking an extreme challenge.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A 3D Vision of Uneven Quality

The transition to a 3D engine was Empire Earth‘s most visible change from Age of Empires. The ability to zoom the camera from a classic isometric view down to ground level was a novelty, allowing players to appreciate the polygonal models of medieval knights or futuristic mechs up close. Unfortunately, this often revealed the low-polygon, dated aesthetics that many reviews derided, especially in the prehistoric and ancient units (“my citizens are ugly!”). Buildings and later-era mechanical units (tanks, aircraft) fared better, but the visual consistency across epochs was uneven.

The sound design was more consistently praised. Unit attack sounds, weapon fire, and ambient noises were considered crisp and effective. The musical score, while competent and atmospheric for each epoch, was often described as “samey” and not as iconic as Age of Empires‘s soundtrack.

The game’s world is built on the Titan engine’s capabilities: dynamic lighting for day/night cycles, weather effects, and destructible buildings that crumble under artillery fire. These elements contributed to an immersive, if graphically dated, battlefield. The massive scale of some maps and the sheer number of units (supporting up to 1,200 per player in custom scenarios) created epic, chaotic war scenes that were the game’s core spectacle. The varied settings—from Greek coastlines to frozen Russian tundras and alien planetary surfaces in the Space Age—ensured environmental diversity.

Reception & Legacy: A Flawed Masterpiece Cemented

Empire Earth received a mixed but generally positive critical reception, with an average score of ~83% on aggregators. Praise centered on its unprecedented scope, depth, and replayability. GameSpy awarded it 2001 PC Game of the Year, stating “it’s almost like getting 14 games in one.” GamingExcellence hailed it as a successful compilation of all human history. Criticism focused on its derivative nature (a “3D Age of Empires“), clunky interfaces (notably the lack of unit descriptions and poor hotkey customization), and the aforementioned AI and epoch pacing issues. GameSpot (7.9/10) and Game Informer (6.25/10) were notably lukewarm, with the latter lamenting that the game “couldn’t walk the walk like it talked the talk.”

Commercially, it was a significant success, selling over 1 million copies globally by 2002 and earning a “Silver” award from ELSPA in the UK and a “Gold” in Spain. Its longevity was cemented not by official support but by a vibrant community. After Vivendi (via Sierra) shut down the official WON multiplayer servers in 2008, fan projects like NeoEE and SaveEE preserved and patched the game, adding modern compatibility and active server lobbies that persist today. The included scenario editor fueled a creative subculture, with users crafting custom campaigns, historical recreations, and entirely new game modes.

Its legacy is complex. It did not revolutionize the RTS genre in the way StarCraft or Warcraft III did; its mechanics were an refinement of the Age of Empires template. Instead, its legacy is one of ambitious synthesis. It proved a single RTS could mechanically support a timeline from cavemen to space marines, influencing later “big history” games and design discussions about epoch progression. It also stands as a cautionary tale about scope—the difficulty of balancing 14 distinct eras meaningfully within a single competitive framework. The subsequent sequels (EE II by Mad Doc Software, EE III) failed to capture the original’s magic, and Stainless Steel Studios shuttered in 2005, unfinished. Empire Earth remains the high-water mark for the series and a cult favorite precisely because of its idiosyncrasies: the brutal AI, the dizzying tech tree, and the sheer, over-the-top joy of fielding a combined army of Roman legions, Napoleonic cavalry, and cybernetic mechs against a digital foe.

Conclusion: The Epic, Flawed Conqueror of Time

Empire Earth is not a perfectly polished gem. Its graphics show their age, its AI is notoriously unfair, its epoch pacing in multiplayer can devolve into a predictable rush, and its interface lacks the polish of its peers. Yet, to dismiss it as merely an “Age of Empires clone with more ages” is to miss its monumental achievement. It is a game of breathtaking audacity, a digital tapestry woven from the threads of every historical war game that came before it. Its campaigns are engaging, scripted epics that make you feel the weight of historical (and fictional) destiny. Its customization systems empower players to create unique civilizations suited to their strategic whims. And its sheer, staggering volume of content—epochs, units, technologies, scenarios—creates a sense of possibility that few games have matched.

For the historian at heart, it offers a playful, interactive timeline. For the strategist, it presents a deeply complex and often punishing system of counters and economies. For the tinkerer, it provides a powerful editor to craft new worlds. Its flaws are inseparable from its character: the cheating AI becomes a legendary barrier to overcome, the rapid epoch shifts a necessary evil for a game that promises 500,000 years. Empire Earth is a monument to a specific kind of early-2000s game development—one driven by a visionary lead designer’s dream to build the definitive historical RTS, realized with more passion than polish. It is, ultimately, an imperfect but unforgettable conquest of time itself, and its place in the history of strategy gaming is secure as the genre’s most ambitiously scoped, enduringly beloved, and chaotically grandiose experiment.