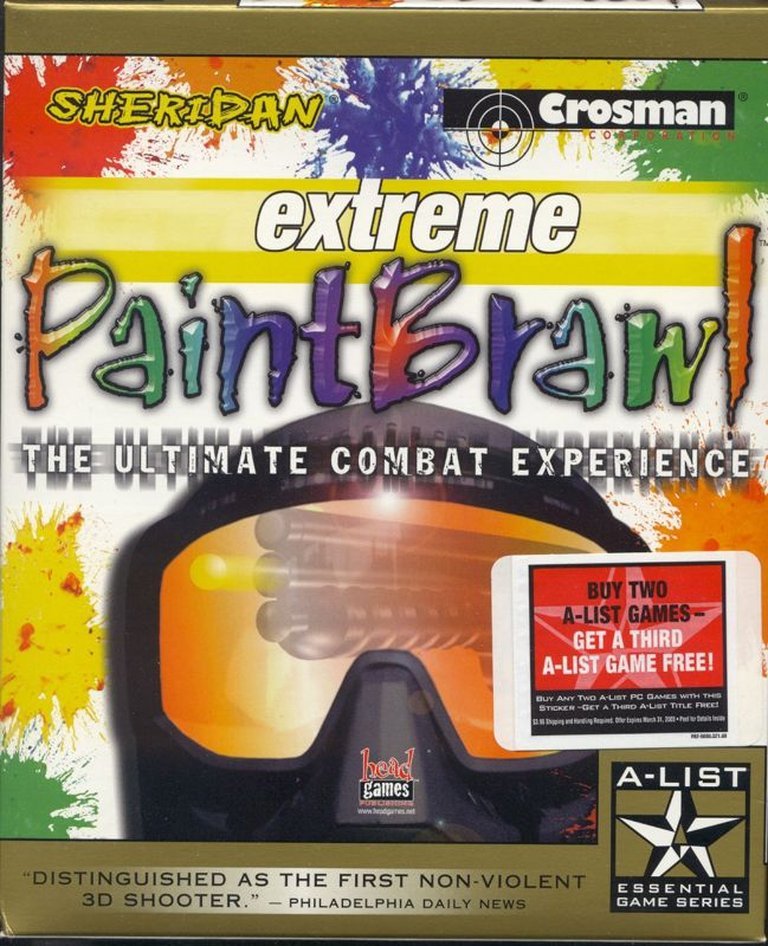

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Head Games Publishing, Inc.

- Developer: Creative Carnage

- Genre: Action, Sports

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Online PVP

- Gameplay: Paintball, Shooter

- Average Score: 17/100

Description

Extreme Paintbrawl is a first-person shooter that simulates the sport of paintball, using the Build engine to create various arenas for players to engage in combat, with support for both single-player and online multiplayer modes.

Gameplay Videos

Extreme Paintbrawl Free Download

Extreme Paintbrawl Patches & Updates

Extreme Paintbrawl Mods

Extreme Paintbrawl Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (17/100): perhaps one of the worst games I’ve seen in years

mobygames.com : Avoid this game at all costs!

Extreme Paintbrawl Cheats & Codes

PC

During gameplay, press Ctrl+Alt+Shift to open the console and type codes, or enter codes as team names or via the talk button during team setup.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| dnclip | No clipping (walk through walls) |

| aye! yo mother was a mounty! | Play as a Royal Canadian Mounted Policeman |

| MAFIA | Cheat mode: maximum ammunition, maximum guns, and the best players |

| iamacheater | Enable cheat mode |

Extreme Paintbrawl: Review

1. Introduction: The Anatomy of a Calamity

In the vast and often tawdry museum of video game history, certain titles stand not as monuments to achievement, but as stark warning signs—cacophonous cairns marking the spot where ambition, hubris, and catastrophic execution collided. Extreme Paintbrawl is one such monument. Released on October 20, 1998, by Head Games Publishing and developed by the obscure studio Creative Carnage, this title did not merely fail; it achieved a peculiar, almost artistic level of failure that cemented its legacy as a contender for the single worst first-person shooter ever conceived. To study Extreme Paintbrawl is to undertake a forensic analysis of a perfect storm of misjudgment: a profound misunderstanding of its source material, a contempt for technological limitations, and a development process so rushed it remains a benchmark for industry folly. This review will dissect the game not merely as a broken product, but as a cultural artifact that reveals the dark underbelly of the late-’90s “extreme” marketing craze and the perilous state of budget game development.

2. Development History & Context: Two Weeks to Infamy

The story of Extreme Paintbrawl is, in itself, the most telling chapter. According to developer trivia and corroborated by designer Carlos Cuello’s own letters to PC Gamer, the entire game was developed from start to finish in two weeks. Publisher Head Games, riding the coattails of the mid-to-late ’90s “extreme sports” fad (their series included Extreme Tennis and Extreme Mountain Biking), imposed an impossible deadline. The studio was forced to use a heavily modified version of the already-antiquated Build engine (famously powering Duke Nukem 3D in 1996), an engine whose sprite-based, 2.5D architecture was looking distinctly prehistoric against the polygon-rich horizons of Quake II and the impending Unreal Tournament.

The context is one of cynical cash-grabbing. The “paintball phenomenon” was indeed a real, growing sport, but translating its nuanced, strategic, and physically demanding gameplay into a digital simulator was a monumental task. Instead of a dedicated project, it was a contractual obligation, a placeholder title in a budget line that received a skeleton crew and a derisory timeline. The source material explicitly states the game shipped without any AI for opposing players; the team was in the process of hastily adapting Duke Nukem 3D‘s bot AI when the gold master deadline hit. This explains the catastrophic, schizophrenic AI behavior that defines the gameplay: teammates mindlessly Gouraud-shaded themselves into walls, while enemies possessed supernatural, wall-hacking aim. The “non-violent 3D shooter” PR claim—a title also erroneously bestowed upon earlier advergames like Chex Quest—was a marketing veneer for a game fundamentally about simulated combat, creating a paradoxical and tone-deaf identity.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Simulation of a Simulation

Narratively, Extreme Paintbrawl is a void. It presents itself as a simulation of the sport of paintball, but the “story” is purely mechanical: you are a participant in a tournament. There is no plot, no characters, no dialogue beyond menu text. The theme, therefore, is one of simulacrum without substance. It simulates the aesthetic of a tactical shooter—the first-person perspective, the weapon selection, the flag capture objective—while utterly failing to simulate the experience of paintball. Where real paintball emphasizes stealth, communication, movement, and the tangible consequence of being hit (elimination), Extreme Paintbrawl reduces it to a broken, chaotic shootout where hits are random, visibility is non-existent, and teammates are liabilities.

The game’s attempt at a “Season Mode,” where you manage a team of eight recruits, highlights this thematic failure. You can hire and fire, buy “markers” (paintball guns), but you cannot even swap weapons between your own team members—a fundamental, game-breaking oversight in a management sim. This isn’t just bad design; it’s a thematic betrayal. The mode promises the strategic depth of team-building and equipment management, hallmarks of professional paintball, but delivers a shallow, broken spreadsheet. The game’s very title promises “extreme” action, yet its core mechanics produce nothing but frustration and absurdity. The theme becomes not “extreme sports,” but extreme dysfunction.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Cascade of Failures

To play Extreme Paintbrawl is to witness a domino effect of catastrophic design decisions.

- Core Loop & Modes: The three modes—Season, Single Game, and Practice—are categorically broken. Practice Mode is a particular insult: you are placed alone on a map with no enemies, no targets, and no objective. It is, quite literally, a virtual labyrinth with no purpose. Single Game is a capture-the-flag variant, but the flag is indistinguishable from the environment, and the maps (an “urban assault arena,” a “haunted forest,” a desert) are bland, labyrinthine collections of blocky textures that bear no resemblance to actual paintball fields, which are typically open, outdoor spaces with natural and artificial bunkers.

- Combat & Weapon Degradation: The central, infamous mechanic is weapon loss. When a player is “marked” (hit), they do not respawn with their chosen marker. Instead, they are forcibly downgraded to a “lousy default gun with paintballs that have trouble gathering up enough velocity to leave the barrel,” as one player review astutely noted. This isn’t a tactical risk-reward; it’s a punitive, game-lengthening annoyance that turns every hit into a major setback, destroying any sense of flow or fairness.

- AI & Team Dynamics: The AI is legendary in its awfulness. Teammates exhibit behaviors described across all sources: getting stuck on doors and walls, standing motionless in open areas like statues, and shooting at nothing (or everything but the enemy). Conversely, enemy AI has “perfect aim,” with nearly every shot connecting. This creates a meta-game where the only viable strategy is to hide and hope an enemy bot wanders into your line of sight before you are instantly killed by their laser-guided paint. The inability to distinguish between enemies and allies—often due to identical sprites and poor color palettes—turns every encounter into a tragicomic guessing game.

- UI & Systems: The graphical user interface is noted as “poor” by Computer Gaming World. The game’s DOS underpinnings (despite a Windows 95 installer) caused compatibility nightmares on newer systems, leading to frequent crashes, as cited by GameSpot. The practice of the engine rendering “about 13 polygons in all,” as a player succinctly put it, speaks to a technical ineptitude that made the game look dated even in 1998.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: An Aesthetic of Failure

Extreme Paintbrawl’s world is a masterclass in missed opportunity and technical bankruptcy. The maps utilize the Build engine’s sprite-based rendering to create environments that are simultaneously incredibly blocky and strangely amorphous. Textures are “shockingly low-resolution,” with no coherent art direction. The “haunted forest” is just a mess of brown and green sprites; the “urban” map is a collection of identical gray boxes. There is no sense of place, no atmosphere, and no functional layout. It does not feel like a paintball field; it feels like a discarded level from a 1995 shareware game.

The sound design is equally infamous. Composer Todd Duane supplied a soundtrack of heavy metal and rock guitar tracks—a bizarre, dissonant choice for a “non-violent” sport. The most infamous legacy is his rendition of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons: Spring on electric guitars, a track so jarringly “extreme” in its mismatched tone that it became a cult talking point, with one reviewer noting it was the only thing “extreme” about the game. Sound effects are tinny, repetitive, and lack impact. The paintball thwip is less satisfying than a mouse click. The entire audiovisual presentation creates an experience that is not immersive, but actively repellent.

6. Reception & Legacy: A Paragon of Panning

The critical reception at launch was not merely negative; it was historically, scorchingly vicious. The aggregate MobyScore of 2.7 (15% from critics) and player average of 1.0/5 tell the story. Key verdicts:

* IGN (0.7/10): Called it perhaps the least fun game imaginable, remarking the soundtrack was the only “extreme” element. This was the second-lowest score in the site’s history at the time.

* PC Gamer (6/100): Declared it an “extreme amount of raw torture,” advising players to seek Quake mods instead.

* GameSpot (1.7/10): Noted it was “out of touch with reality” and “out of step with the gaming world at large,” criticizing its attempt to “wed a tired game engine with the paintball phenomenon.”

* Computer Gaming World (20%): Labeled it a “dud” full of “bugs, crashes, cheesy graphics, worthless AI.”

* Computer Games Strategy Plus (0.5/5): So hated it suggested a group dedicated to destroying it, comparing it to the “Bay City Rollers album” of games.

Its ignominious awards include being Runner-up for Coaster of the Year (Action) by Computer Gaming World and #3 Worst Game in PC Gamer History in 2000. The legacy is twofold. First, it secured an immutable place on “worst games ever” lists (including PC Gamer‘s 2010 “15 worst PC games of all time”), a paragon of catastrophic development. Second, and more bizarrely, it spawned three sequels (Extreme Paintbrawl 2, Ultimate PaintBrawl 3, Extreme Paintbrawl 4), all developed by different studios and all critically panned. This speaks to a grim commercial reality: a game so poorly made it somehow found a niche in the bargain bin, proving that even catastrophic failure can be franchised if the price point is low enough. It stands as a testament to the fact that “so bad it’s good” is a myth for most players; Extreme Paintbrawl is just bad.

7. Conclusion: A Historical Footnote Written in Glitching Paint

Extreme Paintbrawl is not a game to be played, but a case study to be examined. It represents the nadir of several trends: the mindless “extreme” branding of the late ’90s, the exploitation of a popular sport without understanding its essence, the ruthless imposition of impossible deadlines, and the desperation of the budget software market. Its technical failings—the broken AI, the obsolete engine, the crashing DOS-under-Windows shell—are shocking even by the standards of rushed ’90s shovelware. Its thematic failure—a non-violent FPS about a violent sport, with a punishment system that rewards the enemy—reveals a creative vacuum at its core.

In the grand canon of video game history, Extreme Paintbrawl has no place as a work of merit. Its value is entirely as an anti-exemplar. It is the cautionary tale whispered in game development classrooms, the punchline in conversations about notorious flops, and the ghost that haunts the archives of MobyGames with its 2.7 score. It is, as one player review definitively stated, “the worst First-Person Shooter ever made in the history of the universe.” Not because it is ambitious and flawed, but because it is a compilation of every conceivable mistake, born of contempt for the medium and its audience, and given life in a frantic two-week scramble. Its ultimate verdict is not a score, but a categorical warning: avoid at all costs. Its legacy is a monument to how not to make a video game.