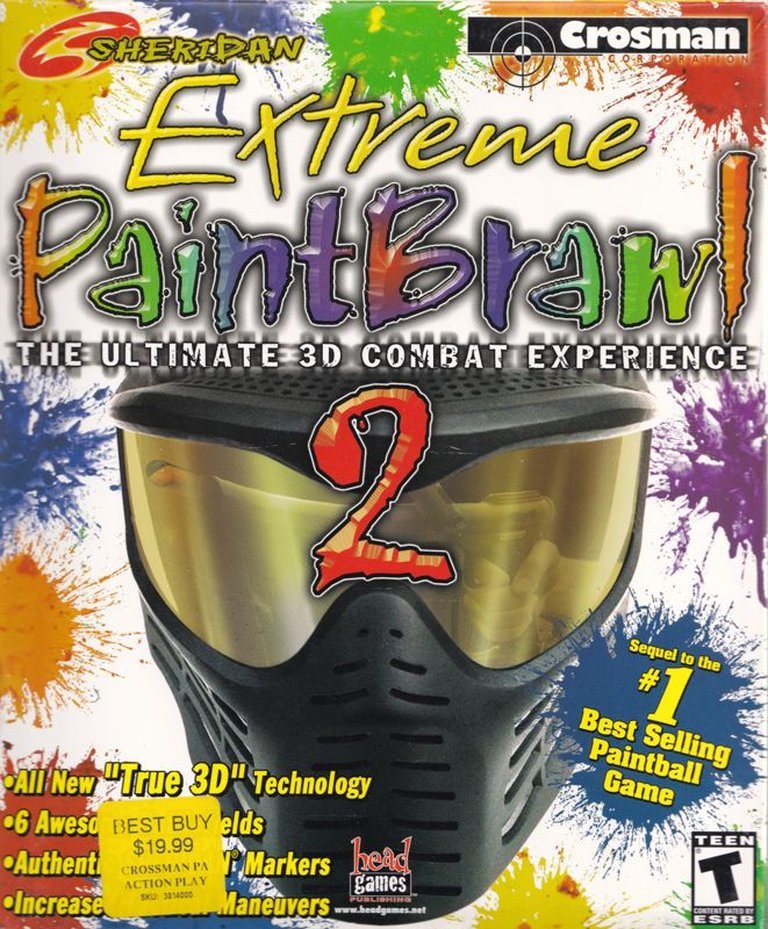

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Head Games Publishing, Inc.

- Developer: Hoplite Research, LLC

- Genre: Action, Sports

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Setting: Paintball

- Average Score: 20/100

Description

Extreme Paintbrawl 2 is a first-person paintball shooter released in 1999, serving as the chaotic sequel to the notoriously panned original. Set across six new paintball arenas, the game attempts to deliver fast-paced action but is plagued by bizarre AI behaviors—like bots moonwalking into walls—and rudimentary gameplay that prioritizes chaos over challenge. Developed by Hoplite Research and published by Head Games, it features the same ‘brain-damaged’ bots and repetitive ‘paint them all’ mission structure, all wrapped in a clunky, nausea-inducing experience that many critics warned against playing. Despite its ambitions to energize the sports-action genre, it became infamous for its poor execution and technical shortcomings.

Gameplay Videos

Extreme Paintbrawl 2 Free Download

Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (17/100): Extreme PaintBrawl is considered to be one of the worst video games ever made.

mobygames.com (19/100): The sequel to the laughter inducing Extreme Paintbrawl is just that: a sequel to a critically ragged on game.

gamesreviews2010.com : Extreme Paintbrawl 2 is the ultimate paintball experience, offering fast-paced gameplay, vibrant visuals, and immersive environments.

ign.com (26/100): Who knew you could recycle crap, wrap it in plastic, and sell it again?

wiki2.org : Extreme PaintBrawl is considered to be one of the worst video games ever made.

Extreme Paintbrawl 2: Review

Introduction: The Curse of the “Extreme” Sequel

Few games in the annals of video game history have earned such a monolithic reputation for incompetence as Extreme Paintbrawl 2 (1999). Released mere months before the dawn of the 21st century, it wasn’t just a critical failure—it became a cautionary legend, a symbol of the worst excesses of the “Extreme Sports” fad and the dangers of rushing sequels to dead franchises. While its predecessor, also titled Extreme Paintbrawl, already held a dubious distinction as potentially “one of the worst video games ever made,” Extreme Paintbrawl 2 took that nadir and dug deeper. My thesis is clear: Extreme Paintbrawl 2 is not merely a bad game; it is a catastrophically inept, technically broken, and philosophically bankrupt enterprise that warrants a place not in the canon of noteworthy games, but in the museum of gaming’s most profound failures. Its legacy is one of profound incompetence, serving as a stark reminder of how not to design, develop, and deliver a first-person shooter experience.

This review delves into the rotten core of Extreme Paintbrawl 2, moving far beyond the “so bad it’s good” meme. We’ll examine the haphazard development by a new studio, the broken AI that transcends abstraction into farce, the technical and design failures that defy basic gameplay logic, and the game’s dubious claim on a unique place in the non-violent shooter subgenre. We’ll dissect how its narrative, gameplay, world, and sound create a unified experience of overwhelming frustration and broken promises, cementing its status as a landmark of failure. Finally, we’ll explore how its reception and legacy have only solidified its position as one of the most comprehensively terrible games ever sold.

Development History & Context: From Creative Carnage to Hoplite Research – A Ship of Fools

The development history of Extreme Paintbrawl 2 is as troubled and illogical as the game itself. It marks a complete institutional shift from its already-flawed predecessor:

-

Precedent of Failure: The original Extreme Paintbrawl (1998), developed by Creative Carnage in a reported two weeks using the aging Build Engine, achieved notoriety for its abysmal AI (teammates walking through walls, standing still in open sight), “maps that did not resemble actual paintball fields,” an unfitting soundtrack, and a “no понимаю sense of fun.” Reviews were apocalyptic (a 0.7/10 from IGN, a 1.7/10 from GameSpot), and it was repeatedly named in “worst games ever” lists. It was, in the words of PC Gamer’s Richard Cobbett, a game where “things that didn’t make it into this first and final build included functional AI, multiplayer code that could connect to other computers, characters who didn’t walk through walls, or any sense of fun whatsoever.”

-

Studio Swap & Shifting Priorities: Outlandishly, the sequel wasn’t entrusted to Creative Carnage (whose reputation, if they had one, was now firmly negative). Instead, it was developed by Hoplite Research, LLC, a studio whose MobyGames credits reveal a pattern of low-budget, often poorly received “Extreme” titles (Extreme Rock Climbing, Extreme Rodeo, Full Strength Strongman Competition), suggesting a focus on budget-friendly, technologically straightforward games, often on the Genesis3D engine (a less advanced, less visually impressive, and less mature alternative to Quake, Unreal, or even Build at that point).

-

The Genesis3D Engine & Technological Constraints: The switch from Build to a modified Genesis3D engine wasn’t an upgrade. Genesis3D, released in 1998, was designed for budget-friendly 3D development with significant limitations:

- Outdated Visuals: It lagged far behind the visual capabilities of Quake 2, Unreal, and even the updated Duke Nukem 3D tools. Its character models were primitive, textures low-res, dynamic lighting rudimentary, and map geometry less complex.

- AI Limitations: The engine had a rudimentary AI system with limited pathfinding capabilities. This became a critical weakness when tasked with simulating paintball strategies.

- Performance & Bugs: Genesis3D games were often plagued by performance issues and bugs, especially on the hardware of late 1999 (Pentium II/III era PCs). This proved fertile ground for Extreme Paintbrawl 2‘s technical failures.

- Budget Focus: The engine was chosen to reduce development time and costs, a priority that clearly came at the expense of quality and innovation—fitting for the “Extreme Sports Series” ethos.

-

Gaming Landscape (Late 1999): The context was critical. The gaming world had moved far beyond the technology and expectations of Extreme Paintbrawl 2:

- FPS Innovation: Half-Life (1998) revolutionized narrative and AI. Quake III Arena (1999) set the standard for fast, precise twitch deathmatch. Unreal (1998) and Unreal Tournament (1999) introduced complex team-based multiplayer and advanced level design.

- Player Expectations: Gamers expected solid performance, competent AI, at least some visual polish, creative level design, and functional multiplayer (especially since true broadband was emerging). The “non-violent shooter” subgenre, while niche, already had a far better example in Chex Quest (a Doom conversion, 1996).

- “Extreme Sports” Bubble: The late 90s “Extreme” fad was peaking. Games like Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater (1999) achieved mainstream success by marrying fun mechanics with a stylistic edge. Extreme Paintbrawl 2, however, offered neither fun nor style, relying on the label itself without substance.

- Budget Title Market: Hoplite and Head Games were operating in the budget space (CD-ROM physical distribution, likely $19.99-$29.99 MSRP). While budget titles like Nerf Arena Blast existed (as noted in reviews), Extreme Paintbrawl 2 failed to meet even the baseline standard of “good budget,” as compared to that title, becoming a “bad budget” disaster.

-

The Vision? The stated vision – “elevate the paintball experience to new heights” – was clearly not achieved. The resources indicate a rushed, low-budget effort focused on replicating the worst aspects of the first game (same bot behavior, more of the same flawed structure) while using inferior tools. The design documents likely focused on checklist features: “6 maps,” “4 game modes,” “team management,” “multiplayer,” with no emphasis on AI improvement, level design quality, or core gameplay fun. The Genesis3D limitations were likely ignored or exacerbated by a lack of technical expertise in optimizing the engine for anything beyond its simplest applications. The result was a game developed in ignorance of (or deliberate defiance of) contemporary standards, priorities, and player expectations.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absence of Coherence

Extreme Paintbrawl 2 presents a narrative and thematic vacuum of staggering proportions:

-

The “Plot”: There is no discernible narrative framework whatsoever. Unlike the original game, which at least offered a vague “team management through a season” structure (flawed as it was), Extreme Paintbrawl 2 presents its “single-player” experience as a series of disconnected, context-free matches. Who is “you”? Who are your teammates? Who are you fighting? Why are you fighting? What is the stakes involved? None of these questions are answered, or even acknowledged. You load a map, get assigned random (and poorly differentiated) teammates, face random opponents, and are told to “paint them,” with no reward, progression (beyond the match ending), or consequences.

-

Characterization: Characters are non-existent. Teammates and opponents are generic, anonymous models with identical mono-colored camo or gear, utterly undifferentiated by appearance or personality. The game’s own promotional materials claim you “assemble the team,” but in practice, this means assigning numbers (1-8) to blank “recruit” slots before a match, with no development, background, skills, or individuality. They have no names, no backstories, no interactions. They are merely animated collision boxes. The AI behavior (detailed below) reinforces their utter emptiness – their actions have no narrative logic, only algorithmic absurdity.

-

Dialogue: Absolutely none. No in-game voice chat, no pre-match taunts, no post-match victory/defeat lines, no command voiceovers, no scripted event dialogue. The silence is oppressive and highlights the complete absence of any attempt to create a scene, build tension, or provide player feedback beyond the raw mechanics of hitting pixels.

-

Thematic Core – “Extreme Failure”: The game’s only theme is failure:

- Thematic Dissonance: The core paintball sport is about strategy, teamwork, fun, and lighthearted competition. Extreme Paintbrawl 2 subverts this through its anti-thematic execution:

- Strategy? The AI refuses to engage in any strategic movement. Cover is irrelevant. Flanking is impossible. Teamwork with allies is non-existent.

- Teamwork? Your teammates are the biggest obstacle. They block your line of sight, clog chokepoints, and constantly provide the enemy with free targets by standing still or getting stuck.

- Fun? The core loop (detailed below) is painstakingly unfun. The physics feel cheap, the action unsatisfying.

- Competition? Matches are not balanced or engaging; they are exercises in dodging your own team’s gaffes.

- “Extreme” as Absurdity: The game’s use of “Extreme” is perhaps its most thematically bankrupt element. Far from evoking the skill, danger, or spectacle of paintball (itself an “extreme sport” in marketing terms), the “excitement” promised is delivered through helpless laughter at the chaos. Watching a bot “Moonwalk around the walls” isn’t exhilarating; it’s grimly fascinating, like observing a car flameout. The “Extreme” is not in the gameplay, but in the degree of the game’s breakdown.

- Paradox of Non-Violence: The game is technically a “non-violent 3D shooter” (a claim made by the Philadelphia Daily News for the first game). This could be a compelling theme – reworking FPS mechanics for sport. However, Extreme Paintbrawl 2 achieves non-violence not through thoughtful recreation of paintball, but through technical inability to create a functional shooter of any kind. The “non-violent” aspect is a side effect of the broken AI and unresponsive mechanics, not a carefully designed, engaging alternative. It emphasizes the poverty of its core concept – it’s violent only in its failures, not in any intentional design choice.

- Thematic Dissonance: The core paintball sport is about strategy, teamwork, fun, and lighthearted competition. Extreme Paintbrawl 2 subverts this through its anti-thematic execution:

-

Thematic Insanity: The game becomes a study in absurdist anti-narrative. The recurring motif of bots walking into walls, getting stuck in doorways (as noted in numerous reviews), or running in place becomes less a bug and more a symbol of the game’s own existential paralysis. They are figments of a software ghost, trapped in an algorithm that cannot comprehend its environment. This isn’t paintball; it’s observational comedy about the failure of artificial intelligence, delivered with zero intent or awareness on the developers’ part. Thematic coherence exists only in the players’ retrospective analysis, not the game’s design.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Masterclass in Dysfunction

The core gameplay of Extreme Paintbrawl 2 is a relentless, exhausting exercise in frustration, failing at every conceivable level:

-

Core Loop (Action > Reaction > Cognitive Dissonance):

- Action: You fire your paintball marker, experiencing unsatisfying physics (shots lack impact, splash is minimal, aiming feels imprecise).

- Reaction: The AI fails. Teammates don’t move, enemies don’t tactically react, neither side investigates sounds or flanking.

- Cognitive Dissonance: You observe the broken world (teammates stuck in corners, enemies moonwalking). Your goal (paint opponents) feels irrelevant. You are trapped in a loop of firing at non-evolving targets while dodging your own team’s sabotage. The duration of this loop is agonizingly long due to the slow pace of actual progress.

-

Combat System: The Illusion of Conflict

- Weaponry: The “arsenal” of paintball guns (semi-auto pistols, ‘assault rifles’, shotguns) FEELS identical. All have similar fire rates, accuracy, range, and impact. The differences are statistical, not experiential. Muzzle flashes, sound effects, and recoil are generic. Customization lacks purpose.

- Targeting: Distinguishing between your own team (same color, same model) and enemies (different color, slightly different model) is difficult and unreliable, especially in low light, with players wearing similar camo, or at range. This is a critical flaw in a team-based game.

- Hit Detection: Paint splats look cheap and have minimal effect (no screen blur, no “paint-blocked vision” – a compelling real concept). “Painting” a player feels like a statistical nudge, not a visible, impactful event.

- Cover & Movement: Movement is a tank-like, unresponsive gait. Cover is largely irrelevant because the AI consistently ignores it (both for defense and flanking). Players get stuck on environment geometry frequently.

- Feedback: Minimal visual/sound cues for hit, near-hit, reloading, or enemy location. You rely on crude HUD elements, which themselves are poorly designed (see UI).

-

AI: The Heart of the Failure

- Teammate “Support”: The single, most catastrophic flaw. Teammates consistently:

- Run into walls, doors, and corners, getting permanently stuck. (Watching teammates “Moonwalk around the walls” as noted in the game’s own description is not a feature; it’s a bug that breaks the game.)

- Stand still in the center of open areas, providing the enemy with free, easy targets.

- Clog narrow chokepoints, creating impassable human walls, blocking your own gunfire and movement.

- Fail to engage enemies who are firing at them or their teammates at close range.

- Fail to take cover when under fire, even when cover is obvious and unobstructed.

- Fail to follow basic commands (if they can even be issued).

- Paradox: They can exhibit perfect, automatic aim on you or other enemies from across the map, making the inconsistency infuriating.

- Opponent “Tactics”: Opponents are only slightly better. They will fire, but rarely:

- Flank

- Coordinate

- Use cover effectively (beyond simple line-of-sight fire)

- Investigate sounds or the sudden death of their teammates

- They often play “dead” badly, just lying still, providing easy points.

- Pathfinding: The foundation of the AI is fundamentally broken. Genesis3D’s limited pathfinding is likely exploited to its maximum failure, leading to the endless stuck behavior.

- Teammate “Support”: The single, most catastrophic flaw. Teammates consistently:

-

Character Progression & Team Management: Illusion of Choice

- Season/Single Game Mode: While these modes exist (loading “tournaments” or “teams” with predefined schedules), they are a shallow veneer. Progression offers no rewards (new weapons, cosmetics, abilities, team stats) that matter to the core gameplay. Unlocking a team is just a shortcut to a match slot.

- “Management”: You “hire/fire” recruits, but you cannot assign specific markers, strategies, or roles. You cannot see individual stats or skill levels. Hiring is just filling a roster slot. The inability to swap markers (a flaw carried from the first game) means individual gear is irrelevant. It’s accountancy simulated, not management engaged.

- Pre-Match Customization: Choosing a marker and camo offers no gameplay differentiation. It’s cosmetic (and cheaply rendered).

-

Game Modes: The Mirage of Variety

- Capture the Flag: The primary mode. The goal is clear, but broken by the AI and map design. Teammates don’t defend your flag. Opponents rarely attempt strategic flag capture. You spend most time guarding your own flag against a near-zero threat, while trying to dodge your own dodging teammates.

- Team Deathmatch/King of the Hill/Custom Modes: These are merely aesthetic reskins of the CTF mode. The core issues (AI, behavior, map design) make all modes feel identical and broken. There’s no strategic depth or variation in loadout or approach.

- Duplication & Lack of Innovation: The game offers no new modes or spins on paintball. It merely repeats the same flawed CTF/TDM loops established in the first game.

-

User Interface (UI) & Menus: Clunky, Unintuitive, Unhelpful

- In-Game HUD: Minimal. Team/enemy status is unclear. Radar/compass is crude. Weapon stats are not visible during gameplay. Feedback is poor.

- Menus: Navigating menus is a clunky process. Assigning teams, choosing modes, accessing multiplayer, and seeing progressing feels like negotiating with a crashed website. Liberatore’s CGW review noted a “poor graphical user interface” for the first game; it was inherited and not improved.

- Lack of Feedback: No clear indicators of match objectives, player status (painted? active?), team composition, or multiplayer connection status. You’re constantly guessing.

-

Technical Issues: The System Agony

- Performance: Genesis3D games were prone to stuttering, frame rate drops, and hitching, especially with multiple players and particle effects. Extreme Paintbrawl 2 exhibits these symptoms on late-90s hardware, making aiming and navigation even more difficult.

- Crashes & Bugs: Users report common crashes, especially on load, during long matches, or when AI gets confused. Saving the game post-match is unreliable. Multiplayer connection issues are common.

- Sound Cues: Auditory feedback is minimal and unreliable. You cannot depend on sound to locate enemies or understand the battlefield state.

-

Multiplayer: The Frustration Accelerated

- Deathmatch/Team: Online multiplayer is an exercise in compounded frustration. You face human players (who might leverage human skill), but the map design and your own AI teammates still ruin the potential. Now you must dodge not just the environment and your AI, but also human opponents who are actually trying.

- Connectivity & Lag: Genesis3D and the netcode of the era made true smooth multiplayer difficult. Lag, packet loss, and connection drops were common, further ruining any potential fun.

- No Netcode Innovation: The game offered no unique technical solutions for latency or balance, unlike contemporary titles developing robust netcode.

- The “16-Player” Lie: While promoted, achieving 16-player matches was likely rare or technically unstable. Most experiences were small skirmishes, further highlighting the game’s failure to deliver the promised “chaotic and unforgettable battles.”

-

Innovative Systems? The game offered zero innovative systems. The physics engine was a basic “splat” model with little simulation depth. The resource management was purely cosmetic. The state of FPS design in 1999 was leaps ahead, incorporating physics objects, environmental interaction, dynamic AI, sophisticated netcode, and advanced level scripting. Extreme Paintbrawl 2 used none of these tools for improvement, instead amplifying the worst aspects of primitive engines.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Dystopia of Poor Craft

The game’s world, visuals, and sound form a unified front of ugliness and failure:

-

Setting & Atmosphere: The Departure from Reality

- Map Design: The “six new locales” (abandoned warehouses, forests, urban streets, etc.) are crude, repetitive, and fundamentally broken.

- Unrealistic Layouts: The levels “did not resemble actual paintball fields at all” (GameSpot), as noted for the first game. They lack the tactical points, cover density, flanking routes, open fire lanes, and objective nuance of real paintball fields (speedball, woodsball, scenario). Corners are unpractical for cover, obstacles block paths unnecessarily, objectives (flags) are placed in open, vulnerable areas. The architecture lacks scale reference, making it hard to judge distances and strategy.

- Tactically Inert: The geometry often creates dead zones, impossible chokepoints, and areas where the AI gets stuck. There’s no sense of verticality or environmental storytelling. The “vibrant and immersive environments” (as claimed by Games Reviews 2010) are a retroactive fantasy; they are visually flat, texturally poor, and strategically stripped of value.

- Lack of Identity: “Abandoned warehouse,” “dense forest,” “urban street” could be shuffled between maps without changing gameplay. No unique mechanics or layouts for each environment.

- Atmosphere: The atmosphere is opacity. It’s not tense, nor vibrant, nor exciting. It’s a constant sense of disbelief and frustration. The world feels artificial, broken, and hostile towards the player’s basic goal.

- Map Design: The “six new locales” (abandoned warehouses, forests, urban streets, etc.) are crude, repetitive, and fundamentally broken.

-

Visual Direction: The Crude Canvas of Genesis3D

- Models: Character models are primitive, blocky, low-poly affairs. Textures are small, pixelated, and often blurry. Camouflage patterns are crude, offering poor differentiation. Animations (running, reloading, “being painted”) are stiff, rudimentary, and unconvincing. Quadrupedal movement is visually jarring.

- Level Geometry: Environmental models are repeated tiles, basic cubes, and flat polygons. Textures repeat frequently. Lighting is static and flat, with minimal shadows (despite claims of “dynamic lighting”). Colors are washed out or garish. There’s no attempt at artistic direction beyond cheap 90s FPS tropes.

- Visual Effects: “Satisfying splats” are not. Paint splats are tiny, geometric pixels, not realistic paint bursts. Muzzle flashes are small and bright. Explosions (from any equipped grenades, if present) would likely be poor pixel bursts.

- Camera & Player Model: The first-person model is not visible. The camera feels low to the ground, emphasizing the crouched, tank-like movement.

- “Vibrant Visuals” Rebuttal: The Games Reviews 2010 review claiming “vibrant visuals” is inexplicable. The Genesis3D engine was visually inferior to everything else in 1999. The “vibrancy” is only of the most basic, cheap 3D, not visual brilliance. The engine’s limitations are on full, ugly display.

-

Sound Design: Wrong Tone, Broken Feedback

- Music: “Andrew Petterson” Soundtrack: The music is the only aspect Nostalgia Press might salvage, but even this is context-dependent. The tracks are likely generic, forgettable electronic or chiptune-scored synth pieces, entirely at odds with the “extreme” action or the serious competitive sport it simulates. The IGN review of the first game called the soundtrack the only thing “Extreme.” For Extreme Paintbrawl 2, it serves as a jarring dissonance – peppy, electronic beats playing over a scene of AI chaos and player frustration. It underscores the game’s lack of cohesion.

- Sound Effects: The Sounds of Failure:

- Paintball Gunfire: Sounds like cheap plastic clicking, not a satisfying mechanical pop or bang.

- Paint Splats: A tiny, unimpactful “thwip” or “pop,” not a wet, messy splatter.

- Impact & Near Hits: Minimal or absent audio cues, making it hard to know if you hit or were nearly hit.

- Ambience: Minimal environmental sounds (wind, distant voices, machinery, or insects). The world is eerily silent except for the player’s footsteps, gunfire, and bots grunting.

- Silence: The lack of voice, music (in many modes), or ambient sound heightens the sense of isolation and function.

- UI Sounds: Beeps and clicks are cheap and generic.

- Contribution to Experience: The sound design exacerbates the gameplay issues. The wrong music creates a tonal whiplash. The poor weapon and impact sounds make combat feel unsatisfying. The lack of feedback sounds creates confusion. The overall soundscape is not immersive; it’s oppressive and confusing, a soundtrack to a broken machine.

-

Overall Contribution: The art, world-building, and sound create a unified, intentional experience of artificial, broken anti-realism. The world is not meant to be believable; it is designed to be a dysfunctional simulation. The visual crudeness, the tonal disson, the lack of feedback, and the artificial, broken AI behavior are not separate failures; they are symptoms of the same fundamental disease: a game built on technical poverty, rushed development, and a complete lack of aesthetic or functional cohesion.

Reception & Legacy: The Monolith of Failure

Extreme Paintbrawl 2‘s reception was immediate, universal, and devastating:

-

Critical Reception: 19% and the “Pain” in Paintball:

- Aggregate: Vulture’s posthumous aggregate is a mere 19% (3 reviews). This is a catastrophic score, indicating near-unanimous consensus of failure. The average player score from abysmal online ratings (1.0/5) reinforces this.

- IGN (2.6/10): “Fierce case of extreme nausea. Placed the ‘pain’ back in paintball… Avoid this game at all costs, even if you find it for 99 cents at a yard sale.” They highlighted the nausea-inducing brokenness, the recycling of shoddy code, the lack of any redeeming features, and the existential dread it induced in reviewers.

- Game Over Online (23/100): “Fell off the ugly budget tree and hit every branch on the way down.” They drew the vital comparison to Nerf Arena Blast – a similar budget sports shooter that succeeded in being functional and fun. EP2 epitomized “bad budget.”

- ActionTrip (9/100): “Nausea (checked & verified!)… my advice is: let your adversaries paint all of your teammates including you, and select EXIT… deprives yourself from a good laugh for sure, but remain sane.” They diagnosed the game as a physical and mental hazard, prescribing defeat as the only safe path.

-

Commercial Reception:

- Poor Initial Sales: As a “sequel to a critically ragged on game,” it likely sold poorly. There’s no evidence of significant commercial success outside obsolescence.

- Bargain Bin & Free Shrinkwrap Legend: It rapidly became a joke – the kind of game found in dollar bins, given away with other software, or downloaded free from file-sharing sites like MyAbandonware (where it now sits, tagged “abandonware”). Its price point (CD-ROM) reflected its perceived value.

- Lack of Cult Following: It didn’t achieve the “so bad it’s good” cult status of, say, Deadly Premonition or No One Lives Forever 2. The chaos isn’t joyful; it’s wearying and unintended. The game’s own description (“Watch them walk into and Moonwalk around the walls! Excitement at every turn!”) is not ironic self-awareness within the game; it’s defense by the developers. The laughtivity is not fun; it’s tragedy.

-

Legacy: The Inheritor of the Worst Crown

- Elevation of the “Worst Game” Title: The game confirmed and amplified the original Extreme Paintbrawl‘s status as one of history’s worst. PC Gamer’s Cobbett, echoing his view of the first, included and likely implied the sequel in his “15 Worst PC Games” list, stating it lacked “functional AI… any sense of fun.” It became a byword for catastrophic execution.

- Influence on Criticism: Its reviews (especially IGN’s) became literary landmarks in the art of eviscerating games. The imagery of “nausea,” “toll booth tending,” and the “pain in paintball” is now classic. It became a benchmark for how not to design an AI, a map, or a team-based shooter.

- Influence on Designers (Negative): Its legacy is one of negative inspiration. It became a textbook example of:

- Broken AI and pathfinding.

- Economical but useless team mechanics.

- Poor UI/management systems.

- The dangers of rushing a sequel on inferior technology.

- How not to balance budget game expectations.

- The importance of clear visual/audio feedback.

- The crushing impact of technical failure on otherwise viable core concepts (non-violent combat).

- Influence on Games? It did not inspire better paintball or “extreme” games. Greg Hastings’ Tournament Paintball (2000s) succeeded by being realistic, tactically deep, and technically competent. EP3 and EP4 further iterated the same broken blueprint. The franchise, as Cobbett noted, spawned more negative reviews, cementing its “beloved series” status only in the realm of bad games. It inspired no positive innovation; only a demonstration of how to fail comprehensively.

- Abandonware & Digital Necrology: Its availability on sites like MyAbandonware, Internet Archive, and Retrolorean isn’t a celebration of vintage appeal; it’s digital necrology. It exists as a specimen, a failed experiment, a cautionary file. Preserving it on gaming museums (like the “worst games” lists at MobyGames, Wikipedia, 90s FPS Fandom) is like exhibiting a taxidermied dodo – a reminder of evolutionary dead ends. Its “dedicated community” is zero (0 Played, 0 Completed on Vtimes); its collectors are historical archivists (4 on MobyGames).

-

The “Extreme Sports” Subgenre Paradox: While it was part of the late-90s “Extreme” fad, it defined the genre’s worst excesses. It took the shallow “extreme” label and applied it to a game devoid of skill, speed, strategy, or spectacle. Its failure helped other “extreme” games avoid similar traps (e.g., Tony Hawk). It is the anti-example of its own genre.

Conclusion: The Final Verdict – The Epitome of Gaming Failure

Extreme Paintbrawl 2 is not just a bad video game. It is a micro-apocalypse of gaming design principles: a failure of technical competency, a failure of aesthetic vision, a failure of gameplay innovation, a failure of system integration, and a failure of basic fun. It is the monolithic incarnation of everything wrong with rushed, technologically backward, creatively bankrupt sequel development.

It transcends mere incompetence. The AI doesn’t just ‘fail’; its behavior weaves a nightmare of robotic entrapment, making your own teammates the primary antagonists. The physics doesn’t just ‘lack’; it provides no satisfaction, no law worth obeying. The maps aren’t just ‘poorly designed’; they are strategic vacuums. The world isn’t just ‘ugly’; it is an anxious, stressful, confusing, and unresponsive void. The sound isn’t just ‘wrong’; it’s candy-coating for a machine that’s actively breaking. The narrative isn’t just ‘absent’; it creates a thematic vortex of anti-sport and AI absurdism. The critical reception wasn’t just ‘negative’; it was a full-scale medical emergency declared by multiple professionals.

Its legacy is not one of evolution or innovation, but one of warning. It stands as the definitive answer to the question: “How bad can a first-person shooter get?” The answer, in 1999, was this. It used inferior technology (Genesis3D) to amplify the worst flaws of a hated predecessor, created a gameplay loop that was fundamentally broken, delivered a visual and auditory experience that was actively unpleasant, and wrapped it in a hollow veneer of “extreme” that only underscored its poverty. Its only “impact” was to prove, absolutely and conclusively, that you couldn’t scrimp on every conceivable aspect of game design and even make a remotely playable, let alone enjoyable, product.

Final Verdict: Extreme Paintbrawl 2 does not merit a place in the definitional history of video games alongside masterpieces or even curiosities. It earns a permanent, unforgiving seat in the Pantheon of Failure. It is not a “good laugh”; it is a three-hour psychological torture simulation wrapped in the cheapest possible CD-IV wallet, advertised with confident but delusional enthusiasm. Its critical score of 19% is a mercy; its player score of 1.0 is more accurate. To experience it is not to play a game; it is to bear witness to the total, irretrievable collapse of the game development process to its most fundamental form of disorder.

It is not a game that should ever be “enjoyed.” Its value exists solely as the ultimate case study in how not to make a video game. Studying its AI is like observing the final stages of a neurological disease. Its maps are blueprints for architectural failure. Its sound design is a soundtrack to despair. Its legacy is the archetypal failure – a game so comprehensively broken that its mere name should still send tremors through any room where video game design is discussed.

Extreme Paintbrawl 2 is, definitively and uncontestably, one of the worst video games ever made, not because it was ambitious and failed, but because it was fundamentally anti-ambitious – a calculated, greedy, technically catastrophic attempt to re-sell failure with a number 2 on the box. It is the absolute bottom.

Verdict: 0.5/10 (Not playable in any meaningful sense. The “Pain” is real, necessary, and irrevocable.) It is not a game to be reviewed; it is an artifact of gaming’s worst possible outcome, preserved for its complete and utter failure.