- Release Year: 2014

- Platforms: PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Windows, Xbox 360, Xbox One

- Publisher: Ubisoft Entertainment SA

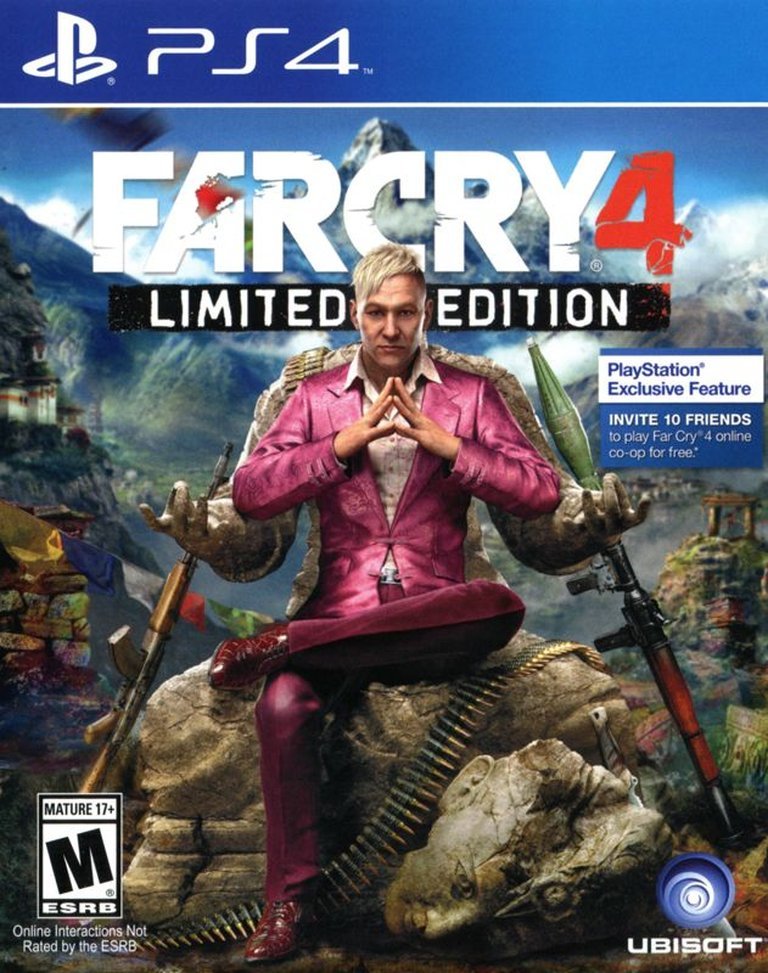

- Genre: Special edition

- Average Score: 84/100

Description

Far Cry 4 is set in the fictional Himalayan nation of Kyrat, where players control Ajay Ghale, a Kyrati-American who becomes entangled in a civil war between the tyrannical king Pagan Min and the rebel Golden Path. The game features an open-world environment for exploration, first-person shooter combat against enemies and wildlife, and role-playing elements like a branching storyline and side quests.

Where to Buy Far Cry 4 (Limited Edition)

PC

Far Cry 4 (Limited Edition) Mods

Far Cry 4 (Limited Edition) Guides & Walkthroughs

Far Cry 4 (Limited Edition) Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (85/100): Far Cry 4 truly shines in the almost bacchanalian sense of freedom it bestows on the player as they traverse through its environment.

ign.com : Far Cry 4 capitalizes on every available strength to make it an amazing open world for first-person action and adventure, while failing repeatedly in creating enjoyable characters within it.

opencritic.com (84/100): At its core, this is just a brilliant, well-designed shooter.

trustedreviews.com : That theme of choice pervades Far Cry 4, too, which is apt given the series has always had a strong sense of exploration, freedom and choice.

Far Cry 4 (Limited Edition): A Definitive Analysis of Kyrat’s Golden Age

Introduction: The Mountain’s Call

In the pantheon of open-world shooters, few entries captured the zeitgeist of their era quite like Far Cry 4. Released at the zenith of the eighth console generation, it arrived not as a revolutionary leap but as a masterclass in iterative refinement—a game that took the potent, chaotic formula of Far Cry 3 and transplanted it into a breathtaking, vertically immense Himalayan kingdom. The Limited Edition, as the default pre-order package, was more than just a bundle; it was Ubisoft’s statement of intent, packing in the Hurk’s Redemption DLC and retailer-specific bonuses like the Blood Ruby mission and 1911 pistol, offering immediate value and signaling a shift towards a perpetual content ecosystem. This review argues that Far Cry 4 represents the apex of the classic Far Cry identity: a beautifully chaotic sandbox anchored by one of gaming’s most mesmerizing antagonists, where player agency in both combat and narrative carved a deeply personal, if flawed, path through a fictional civil war. Its legacy is that of the last entry before the series’ thematic and mechanical pivot towards more provocative, divisive territory.

Development History & Context: From Paradise to Himalayas

Studio Vision & The “We Want It All” Approach

Development at Ubisoft Montreal began immediately after the shipment of Assassin’s Creed III in late 2012. Led by creative director Alex Hutchinson (whose resume included Spore and Assassin’s Creed III), the team initially planned a direct sequel to Far Cry 3 set on the same tropical island, even considering bringing back Vaas Montenegro. In a telling anecdote, this concept was scrapped after a mere four days. The team embraced a “we want it all” philosophy, seeking to experiment wildly. This manifested in core desires: the ability to fly (leading to the Buzzer gyrocopter and wingsuit), and the fantasy of riding a rampaging elephant across “exotic mountainsides” (which directly birthed the Himalayan setting and the elephant作为坦克-like weapon). The goal was clear: a standalone experience. To that end, only two Far Cry 3 characters, Willis Huntley and Hurk, returned, serving as deliberate, universe-spanning connective tissue.

Technical Foundation & Global Collaboration

The game runs on the upgraded Dunia 2 engine, the same core technology powering Far Cry 3, but heavily modified for new verticality and density. Development was a global effort: Montreal handled the main campaign; Ubisoft Toronto crafted the surreal Shangri-La sequences; Red Storm Entertainment built the competitive multiplayer; Ubisoft Shanghai focused on hunting missions; and Ubisoft Kyiv ported the PC version. A pivotal moment in pre-production was a research trip to Nepal. This immersion in local culture shifted the design focus from a generic civil war to the development of unique, believable characters and a rich, exaggerated synthesis of Indian, Nepalese, and Tibetan influences to create the fictional nation of Kyrat.

Release Context & Market Position

Announced in May 2014 and released worldwide on November 18, 2014, for PS3, PS4, Windows, Xbox 360, and Xbox One, Far Cry 4 launched into a crowded shooter landscape. It was a “safe” sequel in a series that had already defined the modern open-world FPS template. The Limited Edition was the pre-order standard, including base game + Hurk’s Redemption DLC, with retailer-exclusive bonuses (e.g., Amazon’s Blood Ruby mission). This edition strategy was symptomatic of an industry moving towards deluxe editions and season passes as norm. Ubisoft projected 6 million first-year sales; the game shattered expectations, becoming the fastest-selling launch in series history and shipping 7 million copies by year’s end, eventually surpassing 10 million units by March 2020.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Family, Betrayal, and the Illusion of Choice

Plot Structure and the Protagonist’s Journey

The plot is deceptively simple: Ajay Ghale, a Kyrati-American, returns to his homeland to scatter his mother Ishwari’s ashes at a place called Lakshmana. Within minutes, his bus is intercepted by the flamboyant dictator Pagan Min, and he is thrust into a civil war between the Royal Army and the rebel Golden Path, founded by his late father, Mohan. The narrative is a classic hero’s journey, but one where the “hero” is a largely silent proxy for the player. Ajay’s primary function is to be a catalyst; his backstory is revealed through gameplay via collectibles (diary pages, propaganda), making his discovery of Kyrat’s history synchronous with the player’s.

The Antagonist: Pagan Min as the Unseen Sun

Troy Baker’s portrayal of Pagan Min is the game’s undisputed masterpiece. Min is a “punk-rock” aesthetic abandoned for something more unsettling: a narcissistic, violently whimsical dictator with a pink suit inspired by Brother‘s Beat Takeshi and Ichi the Killer‘s Kakihara. His charisma is magnetic and terrifying. Crucially, he is rarely the physical obstacle; he is a narrative presence, a ghost in the machine who manipulates events from afar. His relationship with Ajay is the story’s central, bizarre mystery—hinted at through his (spoiler-revealed) past affair with Ishwari and his obsession with the mythical Lakshmana. The infamous Easter egg ending (waiting at the dinner table) isn’t a joke but a profound narrative key, revealing Min’s genuine, if twisted, desire to connect with Ajay and revealing the core family tragedy immediately. This reframes the entire conflict: Min is not a mustache-twirling villain, but a damaged, possessive figure entangled in Ajay’s family history.

The “Civil War”: Sabal vs. Amita and the Illusion of Morality

The Golden Path is led by two diametrically opposed commanders:

* Sabal (Naveen Andrews): A traditionalist who seeks to restore Kyrat’s pre-Min cultural and religious order, often at the cost of progressive values.

* Amita (Janina Gavankar): A revolutionary who advocates for modernity and material strength, embracing drug production to fund the rebellion, but at a profound human cost.

The game’s branching storyline forces Ajay to repeatedly choose between them, with these choices culminating in a binary, dystopian finale:

* Amita’s Kyrat: An authoritarian drug state, with conscripted child soldiers and the disappearance of Ajay’s sister, Bhadra.

* Sabal’s Kyrat: A patriarchal theocracy, with executions of opponents and Bhadra anointed as a religious symbol.

These endings are deliberately unhappy and ambiguous, a subversion of the typical “good vs. evil” climax. The critique here is sharp: whether you choose tradition or progress, the result is a broken state. The player’s agency is the power to choose which form of brokenness prevails, a thematically rich but emotionally hollow victory. This was the team’s stated goal: to twist Far Cry 3‘s narrative, making the outsider (Ajay) the instrument of a flawed revolution, not the savior of a pristine culture.

Shangri-La: The Mythic Counterpoint

The Shangri-La segments, developed by Ubisoft Toronto, are a game-within-a-game—a vibrant, painterly dreamscape where Ajay experiences the legend of the warrior Kalinag. Here, the color palette is strictly controlled (gold for warmth, red for strangeness, orange for interaction, white for purity, blue for danger). This section serves three purposes: 1) It provides a mythological backbone for Kyrat’s culture, 2) It offers a stylistic and mechanical playground (companion tiger, linear set-pieces), and 3) It acts as a narrative mirror to the “real” conflict, framing the Golden Path’s struggle as part of a timeless cycle of violence and myth.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Chaotic Refinement

Core Loop: The Far Cry Trinity

The gameplay adheres to the now-standard Far Cry trinity: Outposts, Hunting, and Side Quests. The world of Kyrat is progressively unlocked by climbing Bell Towers, which reveal points of interest. The primary activity is liberating outposts and fortresses. These are larger and more complex than in Far Cry 3, featuring layered defenses, alarm triggers, and multiple entry points. Success provides fast-travel points and unlocks nearby missions, creating a satisfying “domino effect” of control.

Combat & Player Agency

The combat sandbox is where the game shines. Players have a vast arsenal (from bows to rocket launchers) and tools like the camera for marking, bait for wildlife, and the ability to kick objects/hide bodies—small QoL improvements with big systemic impact. The most iconic new tool is the elephant, a mobile platform that can trample enemies and vehicles. Verticality is key: the Buzzer (gyrocopter) provides aerial reconnaissance and attack, while the grappling hook and wingsuit enable spectacular traversal. The Tiger vs. Elephant skill tree (offensive vs. defensive) is a simple but effective RPG layer.

The “Systems” That Emerge

The magic is in unscripted moments: baiting a leopard into a patrol, calling in Golden Path reinforcements earned via Karma (from helping rebels), surviving a random eagle attack, or watching two enemy convoys clash. These emergent narratives are the engine of the Far Cry experience. The economy—hunting for skins to craft larger wallets and ammo pouches—provides a consistent, satisfying progression loop that encourages exploration.

Multiplayer: Ambitious but Peripheral

Far Cry 4 promised “a lot more multiplayer.” It delivered:

1. “Guns for Hire” Co-op: Drop-in/drop-out co-op for the entire campaign, seamlessly integrated. A standout feature, though bounded by the host’s mission progress.

2. “Battles of Kyrat” Asymmetrical PvP: A unique mode where Rakshasa (magic-wielding, teleporting warriors with bows) battle Golden Path (gun-and-vehicle soldiers). It’s creatively designed but, as critics noted, often felt forgettable and suffered from a small player base and lack of dedicated servers (a persistent issue for Ubisoft’s PvP at the time).

3. Map Editor: Powerful and intuitive, but its inability to create competitive maps at launch was a major misstep, only rectified in February 2015. It fueled a creative community but was ultimately limited.

Weaknesses in the Framework

Critics consistently noted the upgrade system as a lazy carryover from Far Cry 3—uninspiring stat bumps. Some found the helicopter control dull. The random outpost recapture notifications (returning to a liberated outpost to find it “under attack” again) broke immersion and felt like a repetitive gameplay loop rather than a living world. The story missions sometimes forced linear corridors, clashing with the open-world ethos.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Soul of Kyrat

The Vertical World of Kyrat

Kyrat is not just a big map; it’s a dense, vertically layered one. The journey from the lush, Indian-inspired south to the snowy, Tibetan-inspired north is a masterclass in environmental storytelling. As you travel, the architecture, music, and soldier uniforms change, creating a palpable sense of progression into a more oppressive, foreign-controlled heartland. The draw distance is legendary, with snow-capped peaks visible from the southern jungles, constantly reminding you of the scale.

Art Direction and the Two Aesthetics

1. Kyrat: A grounded, chaotic realism with bursts of saturated color (Min’s pink, prayer flags, vibrant wildlife). The world feels lived-in and crumbling, with propaganda posters, distinct village layouts, and a believable (if exaggerated) hybrid culture.

2. Shangri-La: A complete departure—a sacred, geometric, intensely colorful dreamscape. Its strict color theory (gold, red, orange, white, blue) makes it visually unforgettable. It represents the mythic purity the real-world conflict has lost.

Sound Design and Score

Cliff Martinez’s soundtrack is a tour de force, blending traditional Nepalese instruments (like the damphu drum and sarangi fiddle) with electronic pulses and ambient drones. It perfectly captures the duality of Kyrat: the spiritual, melancholy undertones of the culture and the violent, adrenaline-fueled chaos of the gameplay. The sound design for weapons, wildlife, and environmental cues (cracking ice, distant thunder) is crisp and impactful, crucial for player survival and immersion.

Reception & Legacy: The Peak Before the Pivot

Critical Reception: Generally Favorable with Caveats

Metacritic scores: PC 80, PS4 85, XONE 82. The consensus:

* Praised: The open-world design (vibrant, varied, rich), visuals (especially on PS4/X1/PC), soundtrack, Pagan Min as a villain, wealth of content, and co-op integration.

* Criticized: The story was often called tiresome, lackluster, or predictable (especially compared to Min’s scenes). Many felt the game was too similar to Far Cry 3—a polished, expanded iteration but not a bold evolution. Critics from Eurogamer, GamesRadar, and Polygon explicitly called it unambitious and hollow in its innovation, comparing its open-world checklist to Assassin’s Creed and Watch Dogs.

* Multiplayer was universally seen as shallow and skippable, though a few (like IGN’s Mitch Dyer) found the asymmetrical PvP captured the scale of the campaign.

Commercial Success and Lasting Impact

The sales figures speak louder than any mixed narrative critique: over 10 million units. It was a monetary behemoth, cementing the Far Cry series as one of Ubisoft’s flagship franchises. Its influence is in the refinement of the systemic sandbox—the bait-and-wildlife mechanics, the vertical traversal tools, the dense, reward-saturated map. Games like Zombie Army 4: Dead War and even later Far Cry entries (like Far Cry 5‘s outpost system) owe a debt to its design.

The 2025 Re-evaluation: A Timeless Sandbox?

The April 2025 patch that added a 60fps mode to PS5 and Xbox Series X/S is significant. Itallowed a new generation to experience Kyrat with modern fluidity, and discourse has often softened. Retrospectives (like GamingBolt’s “10 Years Later”) argue that Far Cry 4 may have been the last “good” Far Cry—a game that understood the-core premise of a fun, chaotic, player-driven sandbox without the narrative or thematic overreach that later entries (Primal, 5, 6) would be criticized for. Its story, while flawed, is seen as servicable compared to the more divisive narratives of its successors, and Pagan Min remains a high-water mark for video game antagonists.

Conclusion: The Gilded Cage of Kyrat

Far Cry 4 (Limited Edition) is a landmark of iterative game design. It did not reinvent the Far Cry wheel; it polished every spoke, added chrome rims, and sent it speeding through one of gaming’s most stunning and responsive open worlds. Its strengths are monumental: the unparalleled vertical freedom, the iconic, scene-stealing villain, the deeply satisfying systemic combat where an elephant is as valid a tool as a silenced sniper rifle, and a world that feels dense with activity and secrets.

Its weaknesses are equally clear: a protagonist who is a narrative blank slate, a branching story with ultimately cynical, hollow ends, a multiplayer mode that failed to capture the campaign’s magic, and a core gameplay loop that, for all its refinements, can feel familiar to the point of fatigue after 50 hours.

The Limited Edition content (Hurk’s Redemption, Blood Ruby mission, Impaler Harpoon Gun) is solid, crunchy DLC that fits seamlessly into the world, offering more of the core fantasy without altering the main experience. Its real value was in 2014 as a pre-order incentive; today, it’s mostly a historical footnote on the road to the “Gold Edition” and season passes.

In video game history, Far Cry 4 stands as the pinnacle of the classic Far Cry formula. It is the last entry before the series aggressively chased controversial political themes (Far Cry 5‘s cult, Far Cry 6‘s revolution) and primal survival (Far Cry Primal), often at the expense of its pure, unadulterated sandbox joy. It is a game about the chaos of freedom within a rigid, oppressive structure—a metaphor that extends from its gameplay to its legacy. It gave players a breathtaking, broken kingdom to save, and then had the courage to suggest that, in saving it, they might only be choosing the shape of its brokenness. For that audacity, for that scale, and for the sheer, unadulterated fun of riding an elephant off a cliff while shooting a flare gun at a helicopter, Far Cry 4 remains a towering, golden—if deeply flawed—monument in the open-world shooter genre.