- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ARUSH Entertainment

- Developer: Sunstorm Interactive, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hunting, Shooter

Description

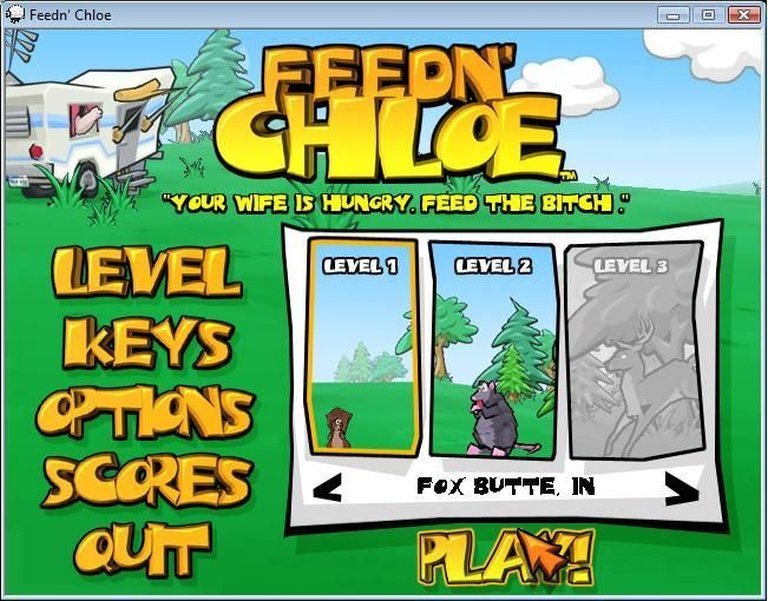

Feedn’ Chloe is a comical first-person hunting game where players embark on time-limited missions to slaughter cartoonish game and generate food for their overweight wife. With a crass and violent tone, it features quirky weapons like double-barreled shotguns, hubcap boomerangs, and explosive cardboard cutouts, and was released episodically for Windows in 2001, targeting adult casual gamers seeking cheap laughs.

Feedn’ Chloe: Review

Introduction: A Curio of Crassness and Experimentation

In the vast and often strangely categorized library of video game history, few titles are as simultaneously obscure, conceptually audacious, and thematically repulsive as Feedn’ Chloe. Released in 2001 by Sunstorm Interactive and published by ARUSH Entertainment, this first-person shooter stands not as a pillar of technical achievement or narrative depth, but as a stark, unapologetic artifact of a specific, fleeting moment in gaming culture. It is a game built entirely on a foundation of deliberate offensiveness, Redneck caricature, and violent cartoon parody, wrapped in a pioneering but ahead-of-its-time episodic distribution model. This review will argue that Feedn’ Chloe is a critical failure by nearly every conventional metric—its gameplay is shallow, its humoraging, and its execution technically rudimentary. However, its historical significance lies precisely in these failures. It serves as a fascinating case study of the early 2000s’ “shock jock” approach to game design, a testament to the risky experimentation with digital distribution, and a clear, if jarring, bridge between the crude humor of late-90s shooters like Duke Nukem and the more focused parody of later titles. To dismiss it as merely a bad game is to overlook its value as a cultural specimen, a game so unabashedly committed to its singular, vile vision that it becomes a window into the less savory corridors of the industry’s past.

Development History & Context: The “Webisodic” Gamble and the Sunstorm Studio

- The Studio and Its Vision: Feedn’ Chloe was developed by Sunstorm Interactive, a studio with a curious portfolio that included the well-received Duke Nukem: Manhattan Project (1999) and numerous hunting and sports titles like the Bird Hunter series. This lineage is crucial. While Duke Nukem cultivated a reputation for crass, hyper-masculine satire, Sunstorm’s other work trended toward straightforward, accessible simulation. Feedn’ Chloe represents a collision of these two impulses: the attitude of Duke Nukem grafted onto the simple, arcade-y structure of a hunting game. The game’s creative vision, as documented in its credits (Lead Designer Jason Smith, Script by Randy Montgomery, Hal Jay, Hugh Savage), was to create a “comical cartoon hunting game” that was “crass and violent.” There is no evidence of deeper ambition; the goal was a concentrated dose of tasteless humor wrapped in a functional FPS shell.

- The Technological Constraints: Built for Windows 95/98/ME/2000 and requiring a 266MHz processor, 64MB RAM, and a DirectX 7.0-compatible 3D card, Feedn’ Chloe was a product of the tail end of the fixed-function pipeline era. Its 3D graphics would have been simple, low-polygon models with basic texture mapping, prioritizing performance and broad compatibility over visual fidelity. The requirement for an 800×600 resolution and 16-bit color was standard but highlights how the technical bar for PC gaming was rapidly rising around it, with titles like Halo: Combat Evolved (2001) setting new benchmarks. Feedn’ Chloe’s tech was not just dated—it was actively humble, aligning with its “budget title” ethos.

- The Gaming Landscape & Episodic Pioneering: The year 2001 was pivotal. The FPS genre was dominated by narrative-driven giants (Half-Life, Halo) and competitive multiplayer phenoms (Quake III Arena, Unreal Tournament). Against this backdrop, Feedn’ Chloe’s premise was radically niche. Its most historically significant feature, however, was its distribution: it was one of the earliest attempts at a true “webisodic” or episodic release model. As Neoseeker explicitly states, it was “released in episodic format meaning you had to pay for each installment separately.” The first couple of levels were free, with subsequent episodes downloadable for “less than $5 each” from portals and the official ARUSH website. This predates the modern episodic model (popularized by The Walking Dead by Telltale a decade later) and was a direct response to the limited bandwidth of the era (requiring a 134MB download per episode) and the nascent culture of digital storefronts. It was a bold, commercially risky experiment that ultimately failed to find a sustainable audience, making Feedn’ Chloe a footnote in the history of game distribution as much as in game design.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Satire Without a Target

The narrative of Feedn’ Chloe is skeletal to the point of abstraction, which is itself a thematic choice. The player is “Ed,” a redneck hunter. The objective is to slay animals (and other designated “game”) to generate food. The motivation? His wife, Chloe, is described in the source material as “fat,” “morbidly obese,” “trailer-hogging,” and possessing a hunger that must be satiated. The “plot” is simply a series of missions across stereotypically named American locales: “Perdy Cistren, AL,” “Cousinville, UT,” and “Fox Butte, IN.”

- Characters as Caricatures: Ed is the everyman protagonist, a blank slate of violent, uncouth determination. Chloe, the eponymous figure, never appears as a character in the gameplay described. She is a distant, motivating force—a symbol of insatiable, gluttonous consumption. Her characterization is pure misogynistic stereotype: the grotesque, nagging, burdensome wife whose only purpose is to drive the male protagonist to action through the promise of food (and implied sexual reward). The other antagonists are equally one-dimensional: “trash-talking bears,” “aliens,” and “other rednecks.” These are not characters but targets, obstacles that embody the chaos and perceived lawlessness of the American backwoods as filtered through a cynical, urbanite parody lens.

- Themes of Targeted Offense: The game’s themes are not explored but flaunted. Its primary theme is the celebration of politically incorrect behavior as a form of rebellion or humor. The hunting premise is a direct parody of both realistic hunting simulators and the broader “redneck” media stereotype (think The Dukes of Hazzard stripped of any charm). The violence is “cartoonish” yet directed at living creatures for sheer sport, framed as a comedic race against the clock. The inclusion of a weapon called the “cardboard babe”—”a cardboard cutout of a bikini-clad blonde that just happens to have C-4 strapped to her back”—is the thematic apex. It combines objectification of women (“babe”), trivialization of explosives (“C-4 strapped to her back”), and the absurdity of a disposable lure into a single, deeply offensive joke. The theme is not “redneck life” but a calculated, adolescent shock-value scenario where the player is invited to laugh at bigotry, gluttony, and violence in equal, broad strokes. The game has nothing to say about these themes; it merely uses them as aesthetic grist for its mill.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Arcade Hunts and Explosive Decoys

The core gameplay loop is disarmingly, even intentionally, simple. It is an arcade-style score-attack game in first-person shooter clothing.

* Core Loop: Each mission presents the player with a time limit. The goal is to kill as many designated targets (squirrels, possums, sheep, deer, bears, etc.) as possible before time expires. Points are presumably awarded per kill, with the score serving as the primary metric of success. There is no narrative progression, no character growth, and no complex world to explore. The level design, as inferred from the named episodes, consists of open-ish wilderness environments or rural maps populated with AI-driven animals that move along paths or flee when shot at. The challenge comes from tracking, aiming, and managing the clock.

* Combat & Weapon Arsenal: The weapon list is a key part of the game’s advertised charm and a direct reflection of its “redneck” parody. It mixes the “standard fair” [sic] with the absurd:

* Standard: Double-barreled shotgun (classic close-range scatter).

* Absurd & Pun-Based: Hubcap boomerang (a projectile that returns), weed whacker (melee or perhaps short-range spray), potato cannon (improvised ballistic), “booby traps” (presumably placed, not carried).

* Signature Mechanic: The “cardboard babe” is the standout. It functions as a deployable lure: animals are attracted to it, congregate, and then the player can detonate the C-4 for a multi-kill explosion. This introduces a minor tactical layer of placement and timing, but it remains a one-note, joke-driven tool.

* Progression & Difficulty: Progression is purely through the three stated difficulty levels: “Simple,” “Purdy Hard,” and “Durn Near Unpossible.” As noted in the Neoseeker description, increasing difficulty makes animals “more elusive, and their counterattacks (if you miss that is) become more devastating.” This suggests a simple AI aggression or damage scaling. There is no persistent character progression, no unlockable weapons beyond what’s available from the start, and no skill trees. The “progression” is the player’s personal skill improvement in the arcade-hunt format.

* User Interface & Flow: The UI would have been minimal: a crosshair, ammo/weapon counter, a timer, and a score display. The episodic structure defined the flow: launch the game, select an episode/mission, complete the hunt, receive a score, and then presumably download the next episode if purchased. The “window” video mode support indicates a likely non-fullscreen or minimalist windowed experience, fitting its casual, downloadable nature.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Crass Cartoon Aesthetics

- Setting & Atmosphere: The world is a series of vignettes of American rural wilderness—forests, fields, maybe a trailer park edge. The atmosphere is not one of tension or immersion but of cartoonish, disposable fun. The title screen and menus likely leaned heavily into the “redneck” aesthetic with crude fonts, gingham patterns, or rusted metal textures. The overall vibe is one of cheap, disposable humor, not a cohesive world to be believed.

- Visual Direction: Described as a “comical cartoon” game, the visual style would have been low-poly, brightly colored (or muddy, depending on the environment), with exaggerated animations for animals (think Looney Tunes-style reactions to being hit). The character models, especially Chloe if she had any representation (perhaps in an intro cinematic), would have been intentionally grotesque caricatures. The art direction’s sole purpose was to facilitate the joke—the “cardboard babe” is a perfect emblem of this: a flat, cheap, sexually objectified cutout rather than a 3D model.

- Sound Design & Voice Acting: The sound design would combine generic FPS audio—gunshots, animal cries, explosions—with a score likely consisting of upbeat, twangy banjo or harmonica music to reinforce the “hicksville” setting. The credits list specific voice actors (Marsha Dangerfield, Chris Hodap, Deaon Smith), suggesting there are in-game voice lines. These would plausibly include Ed’s Southern-fried exclamations, Chloe’s (presumably recorded) nagging or celebratory lines from the menu, and perhaps taunts from the trash-talking bear. The sound, like the art, was a tool for character and comedic timing, judged not on quality but on its effectiveness in delivering the off-color punchlines.

Reception & Legacy: A Whisper in the Digital Wind

- Critical & Commercial Reception at Launch: Feedn’ Chloe existed in a near-total vacuum of critical attention. The single recorded critic review on MobyGames is from GameSpy, which awarded it 73%. The review’s quoted sentiment is telling: “The decision to make it a game for adults was a good one. Hardcore players of the genre wouldn’t give Feedn’ Chloe the time of day. But casual gamers who wanted to rustle up a few hours of cheap laughs and fun should give Feedn’ Chloe a shot.” This encapsulates the game’s destiny: it was neither embraced by hardcore FPS fans nor found a substantial casual audience. Its commercial performance is not publicly documented, but the fact that its MobyGames entry shows only “3 players” who have “Collected By” it over 15+ years is a stark indicator of its commercial failure. The episodic model, while innovative, likely fragmented its audience and complicated its marketing in an era before widespread digital storefront trust.

- Evolution of Reputation & Industry Influence: The game’s reputation has not so much evolved as fossilized. It is cited almost exclusively in databases and discussion threads as a curiosity, often grouped under the “Moorhuhn / Crazy Chicken variants” category on MobyGames. This grouping is profound. Moorhuhn (Crazy Chicken) was a phenomenally successful German series of cartoonish, humorous shooting games. Feedn’ Chloe shares the core “hunt silly animals for points” gameplay but swaps the Chicken’s innocent cartoon violence for aggressive, adult-oriented redneck satire. Its influence is therefore negative and comparative: it is an example of how not to capture the spirit of the Moorhuhn formula for an English-speaking audience. By leaning into mean-spirited stereotypes instead of universal cartoon slapstick, it alienated the very audience it might have reached.

It had no discernible influence on subsequent major titles. Its episodic experiment was not repeated by ARUSH or Sunstorm in any meaningful way. Its legacy is as a dead-end branch on the evolutionary tree of the FPS—a branch that grew from the trunk of Duke Nukem‘s attitude, tried to graft on the fruit of arcade hunting, and withered under the weight of its own offensiveness and poor timing. It is remembered, if at all, for its audacious premise and its failed distribution model, serving as a cautionary tale about niche appeal and the limits of shock value.

Conclusion: A Historically Significant Failure

Feedn’ Chloe is, by any reasonable standard of game evaluation, a poor product. Its gameplay is repetitive, its humor is widely regarded as crude and offensive, its production values are low, and its narrative is nonexistent. It failed to find an audience, left no mark on game design, and its publisher/developer did not build upon it. Yet, to conclude here would be to miss its historical purpose.

This review’s thesis holds: Feedn’ Chloe is invaluable as a cultural artifact. It is a perfect snapshot of a specific, uncomfortable gaming aesthetic prevalent in the late 90s/early 2000s—the era of Duke Nukem 3D, Postal, and Blood—as it attempted to transition into a new decade. It represents a studio (Sunstorm) with disparate talents making an ill-advised lunge for a controversial identity. Most importantly, it is a prime, early example of the episodic game distribution model, a concept that would take another decade to refine and succeed with. Its failure in 2001 highlights the technological and cultural hurdles (bandwidth, payment systems, audience expectation) that stood in the way of what is now commonplace.

In the canon of video games, Feedn’ Chloe does not deserve a place on the shelf of classics. It deserves a place in the archive of curiosities, in the “what were they thinking?” wing of the museum. It is a game not to be played for enjoyment, but to be studied for what it reveals: about the risks of conceptual bankruptcy disguised as transgression, about the follies of distributing software before the infrastructure is ready, and about a segment of the industry that believed crassness was a substitute for craft. Its final verdict is not one of quality, but of significance: a deeply flawed, forgotten experiment that tells us more about its time than a thousand polished masterpieces ever could.