- Release Year: 2009

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: SmallGreenHill

- Developer: SmallGreenHill

- Genre: Action, Puzzle

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Platform, Puzzle

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 100/100

Description

Finwick is a puzzle-platformer set in the enchanting yet perilous Fargrown Forest, where the protagonist begins a summer job delivering mail for the Royal Mail. As he ventures deeper, he uncovers a dying ecosystem overrun by ferocious animals and mutant creatures, prompting him to team up with his friend Pentella to solve environmental mysteries through 79 levels of cooperative puzzle-solving and platforming challenges.

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (100/100): FINWICK BEST GAME FOREVER

digital-tools-blog.com : Finwick is an absolute lovely crafted, triple-A flashgame.

Finwick: A Hidden Gem of Flash-Era Puzzle-Platforming

Introduction

In an era when the web was a wild frontier for gaming, where Adobe Flash served as the digital canvas for indie creators to paint their visions, Finwick emerged as a quiet masterpiece—a puzzle-platformer that wove enchantment through its decaying forest realms. Released in 2009, this browser-based title from the obscure studio SmallGreenHill captured the hearts of players seeking respite from the bombast of mainstream consoles. Its legacy endures not as a blockbuster, but as a testament to the creative potential of flash games, influencing a niche of atmospheric, story-driven indies that prioritized wonder over spectacle. My thesis: Finwick stands as a pinnacle of early 2000s web gaming, blending tight mechanics with evocative world-building to deliver a blissful, if imperfect, adventure that rewards curiosity and patience, cementing its place among forgotten treasures like those from Amanita Design.

Development History & Context

SmallGreenHill, a small independent outfit helmed by developer Jackson Lewis (also credited as Jsonl in some portals), crafted Finwick during the twilight of Flash’s dominance in online gaming. Founded in the mid-2000s, the studio specialized in browser-based experiences, leveraging Flash’s accessibility to distribute games without the barriers of physical media or app stores. Lewis’s vision for Finwick stemmed from a desire to create an “absolute lovely crafted, triple-A flashgame,” as one contemporary review aptly described it—a high-fidelity production in a medium often dismissed as lowbrow. The game’s core concept revolved around a simple delivery gone awry, evolving into a deeper exploration of environmental mystery, reflecting Lewis’s interest in narrative-driven platformers.

The technological constraints of 2009 were both a boon and a bane. Flash Player, at version 10, allowed for smooth 2D scrolling and interactive elements, but limited file sizes and browser compatibility demanded meticulous optimization—resulting in Finwick‘s lean 79-level structure that loaded swiftly even on dial-up connections. This era’s gaming landscape was fertile for such experiments: sites like Kongregate and Newgrounds democratized distribution, fostering a boom in puzzle-platformers amid the indie renaissance. Blockbusters like Super Mario Galaxy dominated consoles, but web games like Finwick carved a niche alongside titles such as Samorost (2003) and the nascent Machinarium (2009), emphasizing surreal, non-violent adventures. SmallGreenHill released Finwick on June 1, 2009, initially as a free demo of the first 25 levels, with the full version unlocking for $5.99—a bold monetization strategy that highlighted trust in its addictive loop. Development likely spanned 12-18 months in a solo or tiny-team setup, drawing from Lewis’s prior flash experiments, and it was ported to Windows executables for broader reach, though browser play remained its soul.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its heart, Finwick unfolds as a tale of reluctant heroism amid ecological peril, a narrative that punches above its flash-game weight through subtle layering. The protagonist, Finwick—a plucky young mail carrier fresh into his summer gig at the Royal Mail—embarks on what should be a routine delivery to the enigmatic Fargrown Forest. This verdant expanse, once a symbol of untamed wonder, has twisted into a nightmarish domain: trees wither under an unseen blight, carnivorous beasts prowl the underbrush, and grotesque mutant fish lurk in subterranean streams. Finwick’s journey pivots when he allies with Pentella, his quick-witted friend (described in sources as his “girlfriend” in some interpretations, adding a layer of interpersonal warmth), to probe the forest’s decay and deliver a crucial missive to a reclusive ecologist.

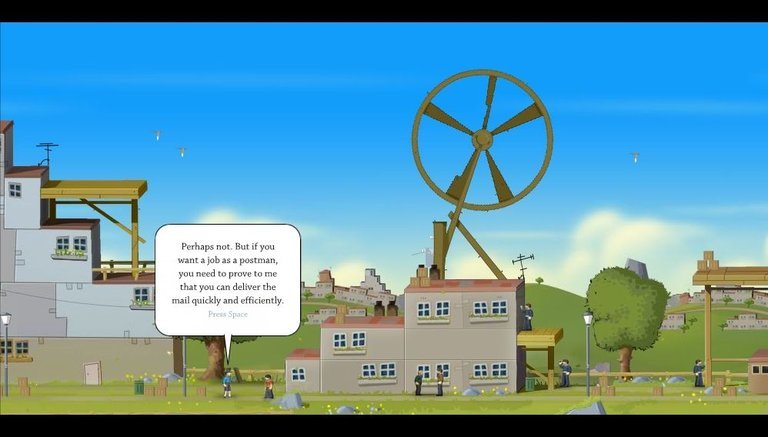

The plot eschews overt exposition for environmental storytelling, a clever choice that mirrors the game’s puzzle-platform roots. Dialogue bubbles punctuate key moments—Finwick’s earnest quips about his “easy job” contrast Pentella’s pragmatic insights, humanizing them as everyday folk thrust into extraordinary peril. Early levels establish the mystery through subtle clues: wilting foliage hints at pollution or a malevolent force, while aggressive wildlife suggests a corruption rippling from the forest’s depths. As players delve below ground in later stages, the narrative crescendos, revealing a “dark secret” tied to human intrusion—perhaps industrial overreach or a forgotten curse—though sources keep the resolution tantalizingly vague, inviting player interpretation. Themes of environmentalism dominate, with the dying forest as a metaphor for real-world deforestation and mutation symbolizing unchecked progress; Finwick and Pentella’s partnership underscores themes of collaboration and resilience, where individual strengths (Finwick’s agility, Pentella’s puzzle-solving savvy) forge unity against chaos. Character arcs are understated—Finwick evolves from naive deliverer to determined guardian—but the dialogue, while well-crafted, occasionally disrupts pacing with its frequency, as noted in reviews, turning rhythmic gameplay into occasional chatty pauses. Overall, the story’s restraint amplifies its themes, creating an intimate fable that lingers like folklore.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Finwick‘s core loop is a masterclass in puzzle-platforming restraint, demanding “fast reflexes and creative problem solving,” as arcade descriptions emphasize. The side-view perspective and 2D scrolling deliver classic platformer fare—jumping across precarious ledges, dodging human-eating critters—but innovate through character-switching mechanics. Players toggle between Finwick and Pentella mid-level, each with distinct abilities: Finwick’s nimble leaps suit vertical navigation and evasion, while Pentella’s environmental interactions (like manipulating vines or luring mutants) enable puzzle resolution. This duality shines in the 79 levels, divided into surface forest romps and subterranean delves; early stages introduce basics (e.g., double-jumps over pits), escalating to multi-phase conundrums where one character activates switches to aid the other.

Combat is minimal and non-lethal, focusing on avoidance—sidestepping charging beasts or timing leaps over snapping fish—keeping the tone exploratory rather than aggressive. Progression is linear yet replayable, with no overt RPG elements but subtle skill gates that encourage experimentation; a level might require Finwick to distract a guardian while Pentella swims through toxic waters. The UI is refreshingly direct: simple controls (arrow keys for movement, spacebar for jump/action, tab for switching) via keyboard interface, with a clean HUD displaying health (tied to environmental hazards) and level progress. Innovative systems include dynamic obstacles, like collapsing platforms synced to the characters’ positions, fostering emergent solutions. Flaws emerge in occasional trial-and-error spikes—some puzzles feel opaque without hints—and the demo’s abrupt cutoff after 25 levels teases the full experience, potentially frustrating free players. Yet, the loop’s “blissful” rhythm, as reviewers rave, lies in its balance: puzzles reward logic without frustration, platforms demand precision without rage-quits, creating an “easy and refreshing” flow that belies its depth.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Fargrown Forest pulses with a tangible, melancholic atmosphere, its world-building elevating Finwick from mere platformer to immersive diorama. The setting—a sprawling fantasy wilderness blending idyllic groves with horror-tinged underbelly—unfurls across biomes: sun-dappled canopies give way to shadowed caverns, where bioluminescent fungi illuminate mutant-infested pools. This progression mirrors the narrative’s descent into decay, with environmental details like barren roots or polluted streams reinforcing the theme of a “dying out” ecosystem. Levels feel alive, not static; wind-swayed branches and rippling water add verticality and depth to the 2D plane, encouraging exploration off the beaten path for hidden lore.

Visually, Finwick dazzles with hand-drawn 2D art that punches far above flash norms—vibrant palettes of emerald greens fading to sickly ochres evoke a hand-painted watercolor style, akin to Amanita Design’s surrealism. Character designs are endearing: Finwick’s tousled hair and mail satchel contrast Pentella’s flowing locks and adventurous garb, their animations fluid yet stylized for quick loading. Sound design complements this mastery; a twinkling, orchestral score swells during discoveries and tenses with percussive stings for dangers, while unique effects—like the squelch of mutant fish or rustle of foliage—immerse without overwhelming. These elements synergize to craft an experience of quiet awe: the forest’s beauty lures you in, its perils heighten tension, and audio-visual cues guide intuition, transforming 79 levels into a cohesive, haunting journey.

Reception & Legacy

Upon launch in 2009, Finwick garnered acclaim in indie circles, though its flash origins limited mainstream exposure. JayIsGames lauded it as a “brilliant gem of a platformer,” praising Lewis’s craftsmanship in an unscored review that captured its unpretentious charm. Kongregate users averaged 3.2/5 from 275 ratings, appreciating the demo’s hours of fun but critiquing load times; player comments on sites like PlayGamesArcade echoed this, with one calling the 26 free levels “really getting into it” before prompting full-version purchases. The sole MobyGames player review, a hyperbolic 5/5 from 2023, hails it as the “100% best game of my life,” underscoring nostalgic appeal. Commercially, the $5.99 unlock model succeeded modestly, with blogs like Digital Tools deeming the demo a “duty to check out,” boosting word-of-mouth.

Over time, Finwick‘s reputation has evolved into cult status amid Flash’s 2020 obsolescence—preserved via wrappers like Ruffle or standalone executables, it influences modern indies like Celeste in puzzle-platforming or Ori and the Blind Forest in environmental themes. Compared to Samorost and Machinarium, it helped legitimize browser games as artistic mediums, paving the way for itch.io-era titles. Its legacy lies in democratizing high-quality storytelling: SmallGreenHill’s output, though sparse, highlighted solo devs’ potential, inspiring a wave of ecological narratives in gaming. Critically, it’s unranked on aggregates due to sparse data, but its enduring “refreshing” vibe ensures quiet reverence among historians.

Conclusion

Finwick encapsulates the ephemeral magic of flash gaming at its zenith—a puzzle-platformer where every leap and switch unravels a forest’s sorrowful secrets, blending accessible mechanics with profound atmosphere. Its minor stumbles, like dialogue pacing, pale against the strengths of its world, art, and innovative duality, delivering a narrative of environmental awakening that’s as timely now as in 2009. As a historian, I verdict it essential: a definitive artifact of indie ingenuity, warranting emulation and rediscovery. In video game history, Finwick isn’t a titan, but a vital whisper—proving that even in digital decay, beauty persists. Rating: 9/10.