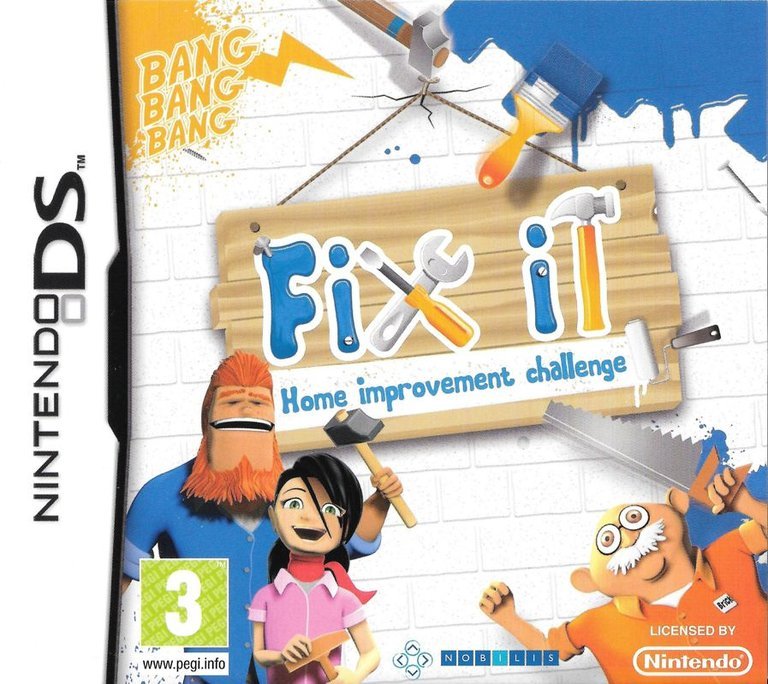

- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Nintendo DS, Windows

- Publisher: Nobilis France, UIG Entertainment GmbH

- Developer: Freedom Factory Studios

- Genre: Action

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Mini-games, Time Attack

- Setting: City

Description

Fix It: Home Improvement Challenge is a mini-game compilation game where players assist the handymen Stonewall and Brick in their DIY business, ‘The Workshop’, by performing various tasks like hammering, sawing, and cutting glass with the Nintendo DS stylus to help customers across a large city. The goal is to earn gold, silver, or bronze medals based on completion speed, unlock trophies for perfect runs, and face boss battles against rival handymen to revitalize the business.

Gameplay Videos

Fix It: Home Improvement Challenge: Review

Introduction: A Nail in the Coffin of Obscurity

In the vast, overstuffed attic of video game history, certain titles gather dust not through infamous failure, but through a quiet, almost complete erasure. Fix It: Home Improvement Challenge (known in parts of Europe as Brico Party) is one such artifact—a 2010 mini-game compilation that arrived at the twilight of the Nintendo DS’s dominance and during the Wii’s saturated “party game” era. Developed by Spain’s Freedom Factory Studios and published by France’s Nobilis Group, this title represents a specific, fleeting moment where the humble premise of “doing home repairs” was deemed a sufficiently engaging core for a full retail release. This review will dissect the game not as a lost masterpiece, but as a revealing case study in period-specific design, constrained ambition, and the pitfalls of relying on a single, gimmicky input method. My thesis is clear: Fix It is a technically competent but creatively hollow experience, emblematic of the shovelware that flooded the DS and Wii, whose primary legacy is as a cautionary tale about thematic execution and the fleeting nature of genre trends.

Development History & Context: Building on Shaky Ground

The Studio and The Publisher: Freedom Factory Studios, based in Madrid, was a developer with a portfolio largely composed of licensed games and budget titles for Nintendo platforms and PC. Their work on Fix It fits squarely within this pattern—a project likely born from a quick, low-risk assessment of market trends. Nobilis Group, the Lyon-based publisher, had a history of family-friendly and niche titles (like the My Baby series) and distribution across Europe. The collaboration suggests a bet on a safe, accessible concept for the mainstream European market, where DIY/home improvement culture has a strong foothold (as hinted by the German subtitle Werkzeugkiste: Reparieren leicht gemacht, meaning “Toolbox: Repair Made Easy”).

Technological Constraints & The DS/Wii Landscape: The game was a dual release for the Nintendo DS (2010) and Wii (2010 EU/2011 NA), with a later Windows port (2013). The DS version is the canonical one, leveraging the touch screen as its sole, defining mechanic. This was the era of the “DS gimmick,” where many games were built entirely around a single stylus-based interaction (e.g., Trauma Center, The World Ends With You). For Fix It, this constraint was both its gimmick and its cage. The Wii version, as noted in the GamePressure database and Dolphin Emulator Wiki, supported the Wii Remote, translating the stylus motions into waggle-based minigames—a direct port that arguably lost the tactile precision the DS version’s core design demanded. The technological ceiling was low: simple 2D sprites, minimal physics, and repetitive sound assets were the norm for such budget titles.

The Gaming Zeitgeist: 2010 was the height of the “party game” and “mini-game collection” boom, fueled by Wii Party, Mario Party 8, and the enduring legacy of WarioWare. Fix It entered a crowded field, seeking differentiation through its specific “handyman” theme. However, it lacked the charismatic branding of Nintendo or the polish of major studios, dooming it to the bargain bin. Its existence speaks to a publisher’s attempt to capitalize on a trend with minimal investment, banking on the broad appeal of its subject matter.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The “Feminine Touch” and Bankrupt Storytelling

Where Fix It attempts narrative is its most problematic and dated aspect. The plot, as summarized on MobyGames, is a stark three-act structure devoid of nuance:

- The Crisis: Brick and his “tough but friendly” associate Stonewall run a failing DIY business, “The Workshop” (or “S&B”). Their niece, Andrea, arrives to find the office a “disastrous mess” and the business bankrupt.

- The Intervention: Andrea employs her “feminine touch” to give the office a “complete makeover.” This is the narrative’s first major, glaring flaw. The trope—that a woman’s presence inherently brings aesthetic order and emotional intelligence to a messy, brutish male domain—is a regressive cliché. It frames the male handymen as competent with tools but incompetent with basic organization and taste, while Andrea’s value is initially presented solely in redecorating, not in technical skill or business acumen.

- The Salvation: Andrea, having prettified the office, then “makes out a list of clients” to restore the business. She transitions from decorator to project manager and de facto CEO, directing the two male technicians. The narrative never explores her own technical skills; she is the planner and motivator, while Stonewall and Brick are the perpetual “doers.”

Characterization & Dialogue: Characters are defined by a single trait. Stonewall is “tough,” Brick is… Brick (the other half of “S&B”). Andrea is the catalyst and bureaucratic force. There is no substantive dialogue reported in the sources, suggesting the story is delivered through static text boxes or silent cutscenes, further flattening any potential for character depth. The customers are faceless “clients throughout a city,” serving merely as nodes on a mission list.

Underlying Themes (Unintended and Otherwise): The game unintentionally posits a bizarre capitalist fantasy: that a failing small business can be saved not by better marketing, loans, or diversification, but by completing a series of arbitrary, physically repetitive tasks for a randomly generated client list. The “city” is not a living entity but a menu screen. The theme of “community improvement” is shallow; you renovate a theater and a “haunted manor” (per Kotaku/LaunchBox), but there’s no sense of civic impact or narrative consequence. The “boss battles against rival handymen” (MobyGames) are the closest the game comes to conflict, but they are framed as competitive minigame sprints, not narrative confrontations. The story is a flimsy scaffold, a misogynistic relic (in its “feminine touch” premise) used solely to justify the gameplay loop, revealing a profound lack of faith in the core activity’s ability to stand on its own.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Grind of Repetition

The core of Fix It is a compilation of over 20 mini-games (GamePressure) categorized as DIY, Decorating, and Gardening, all controlled via the DS stylus. The structure is as follows:

- The Hub: The “Workshop” serves as a central menu. From here, players select clients from a “City” map. Each client provides an “invoice”—a list of tasks.

- The Loop: Tapping a task on the touch screen initiates a minigame. Completion awards a medal (nut fastener) of gold, silver, or bronze based on speed. Tasks are composed of one or more core minigame “verbs.”

- The Verbs: The basic interactions are:

- Repetitive Tapping: Hammering nails, screwing screws.

- Rubbing: Sawing wood, sanding surfaces.

- Tracing: Cutting shapes from glass or other materials (requires stylus to follow a dotted line).

- Mixing: Painting, presumably by stirring or selecting colors.

- Targeting: Possibly for tasks like planting or precise tool use.

- Progression & Rewards: The primary loop is completion for medal collection. A “trophy” unlocks for getting all golds for a client. The “Odd Job” menu allows practicing any minigame in isolation, a crucial (if barebones) feature for skill mastery. The “13 missions to unlock” (GamePressure) likely refer to client chains or city zones, providing a faint sense of progression.

- Boss Battles: The three “boss battles” are described as sequences of minigames to accomplish a larger task, essentially gauntlets of the standard verbs with stricter time limits.

Analysis of Systems:

* Innovation? There is little to none. The mechanics are direct descendants of WarioWare‘s microgame philosophy, scaled up in duration but down in creativity. The tracing mechanic is the most interesting, requiring precision, but it is a single-point solution.

* Flaws: The game’s fatal flaw is systemic repetition. A single client’s invoice might require 5-6 tasks, each taking 10-30 seconds. Multiply that by 13+ clients, and the player is performing hundreds of near-identical stylus rubbings and tapings. The lack of meaningful variation in the core verbs leads to profound fatigue. The medal system provides a slight incentive for replay, but chasing gold medals in a fundamentally tedious activity is a chore, not a joy.

* UI & Feedback: The invoice-on-touch-screen concept is sound, but sources give no detail on on-screen visuals, timer displays, or feedback for mistakes. One can infer a minimalist approach: a task progress bar and a simple “success/fail” chime. The absence of any described hint system or difficulty scaling suggests a rigid, unchanging challenge profile.

* The “30 Tools” Claim: The press release’s boast of “up to 30 tools” is a classic piece of marketing obfuscation. It does not mean 30 unique minigame mechanics. It means 30 cosmetic or slightly varied implementations of the 4-5 core verbs (a hammer vs. a mallet, a handsaw vs. a circular saw). This is a quantity-over-quality misrepresentation.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Cartoon City Without Soul

- Setting & Atmosphere: The game is set in a generic, cheerful “city” where the sky is blue, houses are bright, and problems are purely cosmetic and structural. There is no urban decay to fix, no deep narrative reason for a “haunted manor” to exist. The atmosphere is one of sterile, consequence-free productivity. The Kotaku/LaunchBox description of renovating a theater or space center hints at scale, but these are likely just reskinned versions of the same minigames with different background art.

- Visual Direction: Described as “cartoony” in the press release, the art style is presumably a bright, flat, cel-shaded aesthetic common to early-2010s budget titles. Characters (Stonewall, Brick, Andrea) are “wacky” caricatures. Without screenshots, one can imagine exaggerated proportions, simple animations, and a limited color palette to fit the DS’s screens. The city map is likely a top-down or side-view selection screen with iconic buildings.

- Sound Design: The source material is utterly silent on audio. This is telling. For a game built on rhythmic, tactile feedback, the sound design is paramount. One would expect satisfying thwacks for hammers, the screech of saws, the pour of paint. The absence of any mention suggests generic, repetitive, or forgettable sound assets—another area where budget constraints likely manifested. The music would be upbeat, inoffensive pop or folk tunes, looping endlessly during tasks.

The cumulative effect is a world with no depth, no history, and no stakes. It is a playground for mechanics, not a place with meaning.

Reception & Legacy: The Sound of Silence

- Critical & Commercial Reception: The evidence of its reception is its near-total absence from the record. On MobyGames, it has a “Moby Score” of n/a and is “Collected By” only 1 player. Metacritic lists no critic reviews and no user scores for any platform. The Kotaku page is merely a metadata stub. This is the ultimate sign of a game that failed to register on any critical or community radar. It was not hated; it was not loved; it was unnoticed. Its commercial performance can be inferred as poor, given the absolute lack of digital footprint, presence in “greatest hits” bundles, or cult following.

- Evolution of Reputation: There is no reputation to evolve. It remains a data-point of obscurity. Its listing among “Related Games” on MobyGames alongside titles like Home Improvement: Power Tool Pursuit (1994) and Fix-It Felix Jr. (2012) creates a bizarre lineage of “fixing” games, placing it in a niche subgenre it did not define.

- Influence on the Industry: Zero. It left no mark. It did not inspire clones, nor was it cited as an influence. It represents a dead-end branch of the mini-game genre tree—one that prioritized a thin thematic wrapper over mechanical diversity. Its true legacy is as a cautionary example:

- The Gimmick Trap: Building a full-priced game around a single, simple input mechanism (stylus rubbing) guarantees rapid player exhaustion.

- The Theme-as-Facade: Using a theme (home improvement) not to inspire unique mechanics but to reskin repetitive actions leads to a disconnect between “what you’re doing” and “why you’re doing it.”

- The Budget Ceiling: Without the production values, charm, and design depth of a WarioWare or Mario Party, a mini-game collection is just a collection of chores.

Conclusion: A Job Not Worth Hiring For

Fix It: Home Improvement Challenge is a profoundly average game that achieves a unique form of failure: it is technically functional yet utterly soul-crushing. Freedom Factory Studios and Nobilis correctly identified a potential market—families and casual gamers—but misjudged the ingredients for engagement. They substituted quantity of tasks for quality of experience, and thematic skin for mechanical innovation.

The gameplay is a monotonous rehearsal of physical gestures without the satisfying feedback or escalating creativity of its genre superiors. The narrative is a relic of outdated gender politics, presenting a passive solution (a woman’s “touch”) to a business problem, while offering zero character development. The art and sound are, by all available evidence, serviceable at best and forgettable at worst.

In the grand museum of gaming, Fix It does not deserve a wing or even a prominent shelf. It is a child’s finger-painting hung next to a Monet—acknowledged only to highlight the vast chasm between competent craft and artistic vision. Its place in history is as a footnote, a testament to the fact that even with a clear premise, capable technology, and an existing market trend, a game can fail to be anything more than a digital chore list. It is not a “bad” game in the sense of being broken or offensive (beyond its narrative tropes); it is a vacant game, a hollow experience that perfectly encapsulates the low-expectation, low-reward quadrant of late-cycle platform development. The ultimate verdict? This is a home improvement project best left undone. The resources would be better spent elsewhere.