- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: Windows

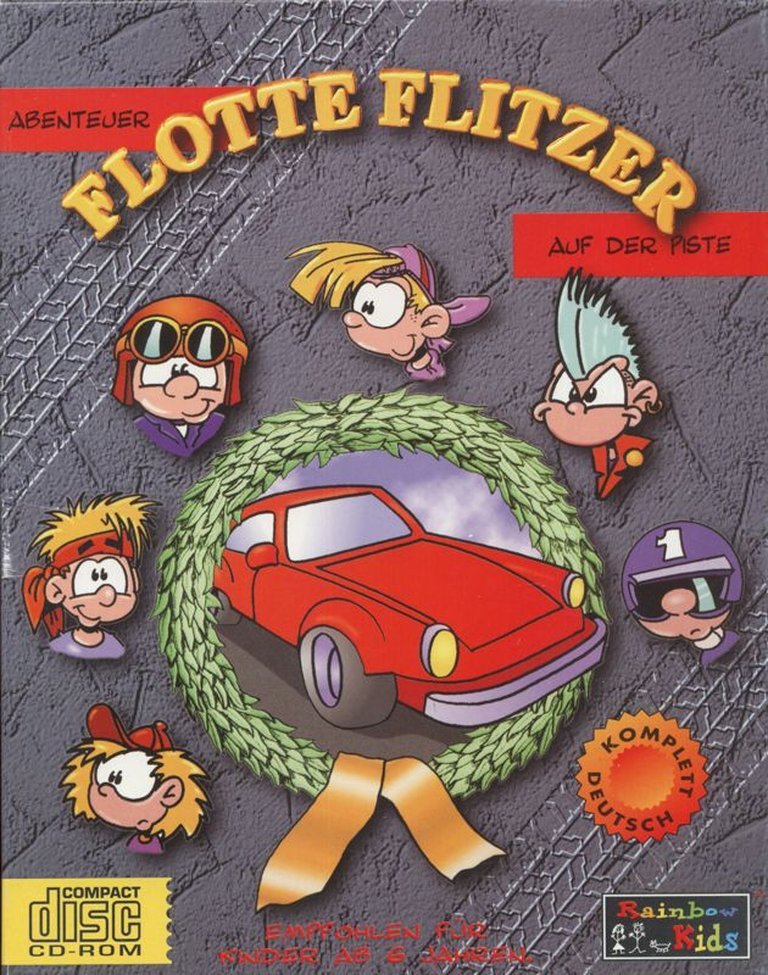

- Publisher: Rainbow Kids

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Mines, Oil spills, Skidding, Upgrades

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

Flotte Flitzer is a racing game aimed at children aged six and older, featuring whimsical character choices like Andy Mc Candy and Susy S. Jim Tonic competing on fantasy-themed tracks viewed from a top-down perspective. The arcade-style gameplay involves skidding, navigating oil spills, and using earnings from top-three finishes to purchase vehicle upgrades or mischievous items such as mines to hinder opponents.

Flotte Flitzer: A Spectral Analysis of a Forgotten 1996 Racer

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine

In the vast, crowded archives of video game history, certain titles exist as mere silhouettes—entries on a spreadsheet, a single line of description, a ghost in the machine of a bygone era. Flotte Flitzer (1996) is precisely such a specter. Released for Windows and published by the enigmatic “Rainbow Kids,” this top-down, 2D scrolling racer aimed at children aged six and older represents a curious archaeological specimen from the precise moment the PC gaming world was collectively sprinting headlong into the 3D polygon rush. With a cast featuring characters like “Andy Mc Candy,” “Susy S. Jim Tonic,” and “Curiy,” and a fantasy-themed track setting, it stands in stark, almost defiant, contrast to the technological manifestos of its year. This review is not an evaluation of a lost masterpiece but a meticulous forensic examination of a footnote. Our thesis is this: Flotte Flitzer is a fascinating artifact of transitional capitalism and developmental pragmatism, a game that likely eschewed the era’s costly 3D trend not through stubborn artistry but through the quiet economics of a smaller studio targeting a specific, underserved demographic. Its legacy is one of near-total erasure, a fate that speaks volumes about the volatile hierarchies of the mid-90s game industry.

Development History & Context: A Studio in the Shadows

The source material provides no credits for designers, artists, or programmers—only the publisher, Rainbow Kids. This anonymity is itself a significant data point. In 1996, the PC gaming landscape was dominated by titans: id Software (Quake), Blizzard (Diablo), Origin Systems (Wing Commander 4), and Westwood (Red Alert). Against these behemoths, a game like Flotte Flitzer would have been a whisper. The publisher name “Rainbow Kids” strongly suggests a focus on the children’s educational or “edutainment” market, a sector that often operated with tighter margins, smaller teams, and less marketing fanfare than the headline-grabbing “core” titles.

Technologically, 1996 was a year of breathtaking but expensive transition. As the architectural blog Lilura1 exhaustively details, the industry was consumed by the 3D revolution: the release of Direct3D, the debut of 3Dfx Voodoo cards, and the pervasive belief that SVGA resolution (640×480) and texture-mapped polygons were the only valid paths forward. Games were bloating onto multiple CD-ROMs, filled with FMV cutscenes. The cost of entry for a 3D racing game—licensing physics engines, creating track geometry, modeling cars, implementing texture mapping—was prohibitive. For a small studio, a top-down 2D racer using sprite-based cars and tile-based tracks was not an aesthetic choice but a survival strategy. It required a fraction of the art assets and development time. The decision to target “kids aged six and older” further clarifies this: a simple, accessible control scheme and bright, cartoonish fantasy visuals were perfectly aligned with a low-risk, low-budget production model. Flotte Flitzer was not competing with Need for Speed or Grand Prix 2; it was competing for shelf space in the “Kids & Family” aisle of a software retailer, a space increasingly crowded with licensed properties and cinematic experiences it could never afford to mimic.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absence of Story

Here, the forensic approach hits a absolute wall. The source material offers zero narrative details. There is no plot synopsis, no description of a world, no explanation for characters named “Andy Mc Candy” or “Curiy.” The “fantasy” setting is a genre tag, not a world. This vacuum is, in itself, analytically rich.

For a game aimed at the youngest segment of the PC gaming market of 1996, narrative complexity was likely minimal to non-existent. The “story” was almost certainly the race itself. The character selection served a simple functional and aesthetic purpose: providing visual variety and a slight sense of ownership (“I am Jim Tonic!”). The names are puns (“Candy,” “Tonic”) suggesting a lighthearted, confectionery-themed fantasy world, but without any supporting text, cutscenes, or dialogue snippets, this remains pure speculation. Thematically, the game’s loop of winning races to earn currency for upgrades (“better tyres, stronger engine… or small devilries like mines”) promotes a clear, Capitalist-Fantasy ethos: success in competition (the race) begets material improvement, which in turn begets further competitive success. The inclusion of “devilries like mines” introduces a subtle, age-appropriate element of sabotage and tactical mischief, framing competition not just as speed but as strategic cunning. Yet, without a narrative framework to contextualize these actions—are these races for a championship? A magical tournament?—the themes remain primitive and implicit, existing solely within the game’s mechanical loop.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Arcade Loop, Laid Bare

From the single paragraph description, we can reconstruct the core gameplay loop with clarity, noting both its apparent strengths and the glaring unknowns:

- Perspective & Control: A top-down, 2D scrolling view with “direct control.” This implies keyboard or joystick input for acceleration, steering, and braking, with a likely emphasis on responsive, arcade-style handling. The mention of “skidding” confirms a physics model prioritizing fun slide mechanics over simulation.

- The Race: Tracks are the arena. The presence of “oil spills” indicates static hazards placed on the track, requiring pattern memorization or quick reflexes to avoid. This is a classic arcade racer trope that adds难度 without complex AI.

- Progression & Economy: This is the game’s most defining systemic feature. Finishing in the top three (“podium finish”) awards in-game currency. This currency is spent in a shop on two categories of upgrades:

- Performance Parts: “Better tyres, stronger engine, more stable bodywork, harder shock absorbers.” These represent classic stat upgrades: handling/traction (tyres/suspension), top speed/acceleration (engine), and durability (bodywork/shocks). This creates a tangible progression system where success in early races enables superiority in later ones.

- *”Small Devilries” (Items):” Mines that make life difficult for the other drivers.” This introduces item-based competition, directly lifting a core mechanic from kart racers like *Super Mario Kart (1992). The use of mines suggests a limited inventory or single-use purchase per race, adding a layer of strategic spending—do you buy a permanent performance boost or a temporary race-altering weapon?

Missing & Unknowable Systems: The source is silent on critical questions. How many tracks? Is there a championship mode or single races? How many characters, and do they have differing base stats? What is the nature of the AI—rubber-banding, aggressive, passive? Is there a time trial or multiplayer mode (likely via IPX/Serial, standard for 1996 DOS/Windows games)? The absence of any critic or player reviews means we cannot know if the upgrade system was balanced, if the tracking AI was competent, or if the handling felt good. We are left with the blueprint but not the experience.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Fantasy Through a Practical Lens

The “fantasy” setting is presented as a counterpoint to the realistic racing simulations of 1996 (Grand Prix 2, NASCAR Racing 2). With no screenshots in the provided sources, we must infer from genre conventions. A top-down 2D racer for young children in a fantasy setting likely featured:

* Visuals: Bright, saturated colors. Tracks might wind through candy-colored castles, mushroom forests, or cookie-cutter landscapes. Cars were probably whimsical, creature-like vehicles (e.g., a candy-coated beetle, a tonic bottle on wheels) rather than licensed automobiles. The 2D scrolling visual style means the art was almost certainly pre-rendered sprites or hand-drawn tiles, a deliberate cost-saving measure that, ironically, may have given the game a more cohesive and stylized look than the muddy, low-polygon 3D tracks of some of its contemporaries.

* Sound Design: Presumably upbeat, melodic music and simple, clear sound effects for engine roars (likely cartoonish), collisions, and item usage. Voice clips for character catchphrases were possible but not guaranteed given budget constraints.

* Contribution to Experience: The fantasy veneer served a dual purpose: it justified non-realistic vehicle designs and track obstacles (oil spills could be “slime puddles”), and it softened the competitive aggression of racing and item-based sabotage, making it palatable for a child audience. The top-down view ensured clarity and accessibility, removing the disorientation that early 3D could sometimes cause.

Reception & Legacy: The Sound of Silence

The most damning and informative evidence is found in the “Reviews” sections on both MobyGames and Metacritic. There are zero critic reviews and zero user reviews recorded for Flotte Flitzer. The MobyGames entry notes it is “Collected By” only 1 player. This is the ultimate reception metric: total obscurity.

We can deduce its contemporary commercial performance was abysmal. It left no mark on sales charts, garnered no magazine coverage (in the sources provided), and was seemingly forgotten immediately after release. Its “legacy” is purely as a data point. It represents the countless games that flooded the budget bins of software stores in the mid-90s, games that were produced, distributed, and then vanished without a trace. Its existence confirms the brutal Pareto Principle of the industry: a tiny fraction of titles capture all the attention and historical memory. Flotte Flitzer is in the vast, uncared-for 80%.

It had no discernible influence on subsequent games. Its core loop—top-down arcade racing with upgrades and items—was already perfected by series like Mario Kart. Its fantasy theme was common in children’s software. It contributed no technical innovation, defined no genre, and inspired no successors. It is a dead end.

Conclusion: A PerfectlyForgotten Game

Flotte Flitzer cannot be judged as a failure or a success in traditional terms; it is a historical null. It was a product of its time in the most banal way: a small publisher leveraging the final, accessible years of 2D sprite-based game development to produce a cheap, focused product for a niche market, only to be utterly overwhelmed by the 3D tsunami and the marketing might of larger competitors.

Its place in video game history is not one of importance but of illustration. It is a perfect case study in the economics of obscurity. It shows that the 1996 gaming landscape was not just Quake and Diablo, but also a sprawling underbelly of anonymous, forgotten titles that sustained the retail shelves but failed to sustain themselves. The game’s complete absence from critical discourse and player memory is its most defining characteristic. It is less a game and more a ghost—a reminder that for every title enshrined in a “Best of 1996” list, dozens, if not hundreds, of Flotte Flitzers faded into the digital ether, their circuits cooling for the final time, leaving behind only a single, cryptic line in a database: “A racing game… Andy Mc Candy… oil spills… mines.”

Final Verdict: Historically significant only as an exemplar of total commercial and cultural failure in a hyper-competitive transitional era. As a playable experience, it is a lost artifact; as an object of study, it is a silent testament to the ruthless Darwinism of the game industry. It earns not a star rating, but a solemn mention in the ledger of the forgotten.