- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: SnapDragon Games GmbH

- Developer: SnapDragon Games GmbH

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Combos, Mission-based, Scoring, Shooter

- Setting: Urban

Description

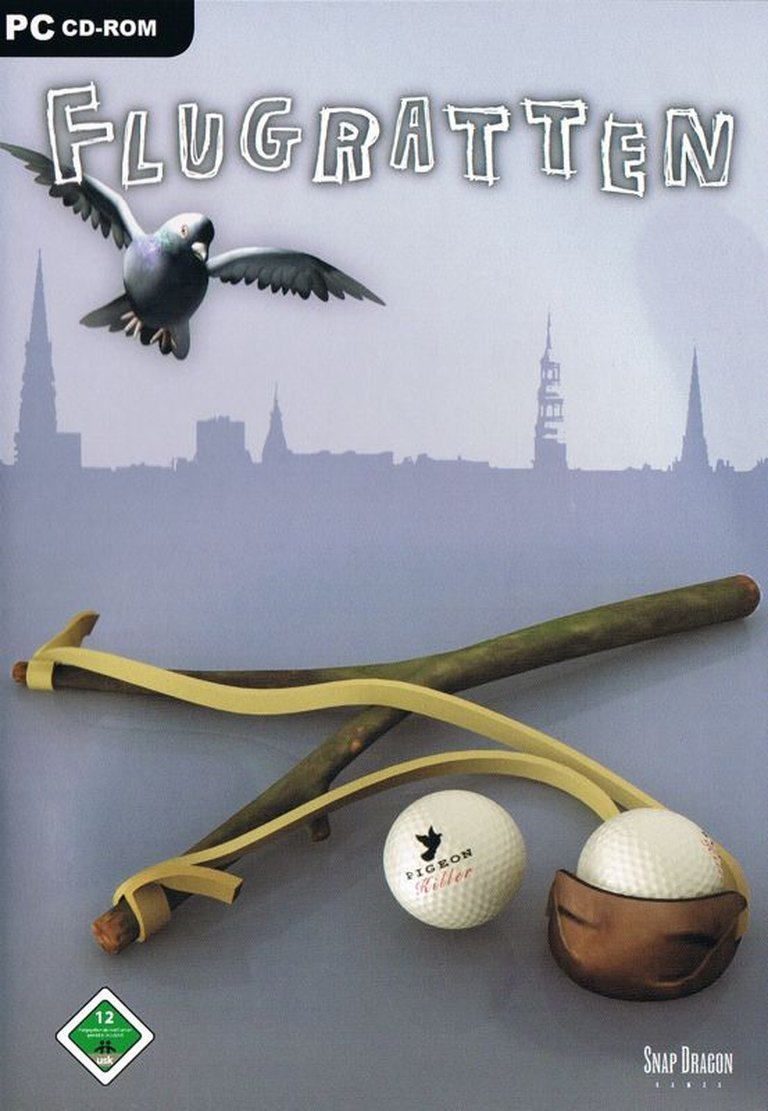

Flugratten is a first-person shooter where players use a catapult to hunt pigeons and protect iconic buildings in cities like Hamburg, Munich, Berlin, Amsterdam, Salzburg, Paris, and Venice from pigeon droppings across 21 unlockable missions. By luring pigeons with food such as burgers and croissants, players earn points through combos and long-distance shots in this quirky action game developed by SnapDragon Games GmbH.

Flugratten Patches & Updates

Flugratten Cheats & Codes

PC

Run the trainer and press F1 during gameplay for unlimited ammo.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| F1 | unlimited ammo for all weapons/items |

Flugratten: A Eulogy for Europe’s Most Peculiar Pest Control Simulator

Introduction: The Pigeon Problem and a Curious Solution

In the vast, overcrowded museum of video game history, some titles are enshrined as masterpieces, others as notorious failures, and a few million more slip silently into oblivion, their cartridges and CDs becoming unmarked tombstones in bargain bins. Flugratten (2006) by SnapDragon Games GmbH belongs unmistakably to this final, most enigmatic category. It is not a game celebrated for revolutionising graphics, narrative, or gameplay. Its legacy is not written in metacritic scores—which, per the available data, are non-existent—but in a single, bizarrely specific premise: a first-person action-shooter where you defend the historic monuments of Europe from the existential threat of… pigeon guano, using a catapult and an arsenal of edible projectiles. This review posits that Flugratten is a fascinating temporal artifact, a snapshot of a specific moment in mid-2000s German-developed casual gaming. It embodies a quirky, locality-driven design ethos, marrying a simple, almost arcade-y core loop with a hyper-specific European setting, all while operating within the technical and market constraints of a small studio. Its true subject is not pigeon slaughter, but the peculiarities of regional humour and the ambition to build a quirky, full-priced title in an era increasingly dominated by either Hollywood blockbusters or browser-based casual fare.

Development History & Context: The Hamburg Garrison

Flugratten emerged from SnapDragon Games GmbH, a Hamburg-based studio making its debut as a developer (though the credits note it as both developer and publisher, with edel distribution handling wider physical distribution). The mid-2000s was a transitional period for the German games industry. It was no longer the era of pure Amiga/PC shareware hits, but not yet the indie explosion facilitated by digital storefronts. For a small team—49 credited individuals across design, programming, art, sound, and QA—the path to market was still paved with CD-ROMs, retail partnerships, and a reliance on local publishers like edel.

The game’s vision, as articulated in the German press release from Games-Guide, was clear: create a “witzige” (funny/witty) and “schnell süchtigmachende” (quickly addictive) experience. Executive Producer Christian von Duisburg’s quote about investing in “Qualitätssicherung und den letzten Feinschliff” (quality assurance and the final polish) suggests an awareness of the need for a polished, complete product, not just a prototype. The technological constraint was the standard PC of 2006: Windows XP/Vista era hardware, with DirectX 9-era 3D capabilities. The source material mentions a “State of the Art 3D-Engine” with specific features like pigeon ragdolls, flight formations, and AI/food-seeking characteristics. This points to a team attempting to punch above its weight technically, implementing basic physics and behavioural AI for the avian antagonists—a non-trivial task for a small team.

The gaming landscape of late 2006 was dominated on PC by The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, Gears of War (on Xbox 360), and the rising tide of online shooters like Battlefield 2 and Counter-Strike: Source. Against these behemoths, Flugratten’s choice of a first-person perspective for a non-violent (towards humans), almost satirical shooter was a deliberate niche play. It wasn’t aiming for the hardcore FPS audience but for a broader, casual-to-core audience (“sowohl Casual- als auch Core-Gamer umfasst,” as Mathias Czychy of edel stated). Its theme—urban pest control in picturesque European cities—was profoundly local, reflecting a sense of humour and cultural touchstones (Hamburg, Munich, Berlin, Amsterdam, Salzburg, Paris, Venice) that would resonate primarily with a Central European audience.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The War on Feathers

Flugratten’s narrative is not a story but a detailed municipal crisis. The premise, delivered via the game’s description and promotional blurbs, is one of ecological and cultural warfare. The enemy is Columba livia—the common city pigeon—dubbed “Flugratten” (flight-rats), a derogatory German term immediately framing them as vermin. The stakes are the preservation of “wertvolle Monumente” (valuable monuments) from “Verschmutzung” (soiling/defilement).

There are no characters, no dialogue, no plot twists. The “narrative” is expressed purely through mission objectives and environmental storytelling. Each of the 21 missions across 7 cities tasks the player with protecting a specific landmark—the Hamburg harbour, Munich’s Marienplatz, Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Amsterdam’s canals, etc. The theme is a whimsical yet fervent civic nationalism. You are not a soldier, spy, or adventurer; you are an anonymous civic guardian, a one-bird (well, one-pigeon) clean-up crew. The humour is derived from the absurd juxtaposition of high-stakes monument defense with low-brow weaponry. The promotional material lists a chaotic array of ammunition: “Tomaten, Äpfel, Burger, Brötchen, Croissants, Ketchupflaschen, Brezeln, Bierdosen” (tomatoes, apples, burgers, rolls, croissants, ketchup bottles, pretzels, beer cans). This is a kitchen-sink approach to projectile warfare, where a stale pretzel is as valid as a tomato. The deeper, unspoken theme is humanity’s eternal, futile battle against the natural world’s messiness, packaged as a cathartic power fantasy. The pigeons are not just birds; they are an unstoppable, defecating tide of chaos against which civilisation must erect a futile, comical defense.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Loop of Luring and Launching

The core gameplay loop is deceptively simple yet, according to its own design, possesses strategic depth.

- Attraction Phase: The player uses food items (from the aforementioned list) as bait to lure pigeons into a specific area or into flight patterns conducive to targeting. This introduces a tactical layer: where and when to place bait to create clusters or high-value shots.

- Engagement Phase: Armed with either a Standard or Pro Zwille (catapult/slingshot), the player must aim and fire. The distinction between catapults hints at a potential upgrade system or differing stats (power, range, reload speed), though specific stats are not detailed in the sources.

- Scoring & Combos: Points are awarded per pigeon. Combos (multiple kills in quick succession) and long-distance shots grant bonus points. This encourages a playstyle that values accuracy and rhythm over mere spray-and-pray. The high score chase and online leaderboards are cited as key motivators, placing it firmly in the arcade tradition.

- Mission Structure: Clearing one mission unlocks the next, creating a linear progression through the 7 cities. The “Missions in Bronze, Silber, Gold” (Bronze, Silver, Gold) mentioned in the features list suggests a tiered achievement system—perhaps time trials, score thresholds, or special challenge modes like “Last Man Standing,” “Sniper,” “Grillmeister” ( Grill Master?), “Möbelpacker” (Mover?), “Spiel-Satz-Sieg” (Game-Set-Match?), and “Berserker.” These evocative German names hint at varied objectives beyond simple pigeon culling, though their exact mechanics remain a mystery from the sources.

- Environment Interaction: The game world is not a static backdrop. The description mentions “witzige Gimmicks” like a balloon stand, cement mixer, electrical wires, and vehicles (balloon, airplane, tram) that can presumably be used as impromptu weapons or for traversal. This suggests a physics-based, playful interactivity that was likely a hallmark and selling point. Solving a pigeon problem by triggering a cement mixer or harnessing tram power would be the kind of emergent, chaotic fun the team presumably cherished.

- The “Flugratten” AI: The credited “AI/Fresscharakteristik” (feeding characteristic) implies pigeons have behaviours tied to food sources. They would likely flock to bait, have wander patterns, and perhaps flee when a compatriot is launched into the stratosphere. The “Pigeonragdoll” physics are a clear technical point of pride, meaning hit pigeons would react physically to impacts before falling.

Flaws & Innovations: The core flaw is inherent in its scope: a full-price retail game built on a single, potentially repetitive mechanic. Long-term engagement would hinge entirely on the quality of that loop and the variety provided by the city layouts and gimmicks. The innovation lies in its committed absurdity and its fusion of casual bait-and-shoot mechanics with a serious 3D engine and a tourist-brochure setting. It was likely the first (and perhaps only) game to treat the Battle of Trafalgar or the canals of Venice as a backdrop for a food-based avian extermination Sim.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Postcard of Pestilence

The world of Flugratten is a stylised, almost caricatured Europe. The 7 cities are not simulated but represented—their famous squares and monuments rendered in 3D. The artistic direction was handled by Stefan Elsner, Manuel Scherer, Mika Kreitschik, Meike Deutscher, and Björn Eilertson. Given the team’s size, the art style was likely a blend of low-to-mid polygonal models with colourful, hand-painted textures, aiming for a bright, cartoonish, and accessible look rather than photorealism. The goal was recognisability (you know you’re in Paris because there’s a stylised Eiffel Tower), not historical accuracy.

The atmosphere is one of playful satire. The visual tone is sunny and vibrant, clashing comically with the grim (if cartoonish) task of guano defence. The sound design, by toneworx, Jörg Mackensen, Andreas Gensch, Johannes Semm, and Tatjana Gensch, and music by Flash Analogue, Boris Royko, Semm, and Ulrich, is crucial in setting this mood. One can imagine cheerful, perhaps oompah-tinged or accordion-heavy folk melodies for German cities, switching to a generic “French” cabaret tune for Paris, all underscored by the satisfying thwack of the catapult, the squawk of a pigeon, and the splat of tomato impact. The sound of a beer can hitting a pigeon in mid-flight would be a key auditory reward. The inclusion of professional sound designers suggests an effort to make the visceral feedback of the core action as satisfying as possible.

Reception & Legacy: The Ghost in the Machine

Contemporary reception is a virtual void. There are no critic reviews aggregated on Metacritic (“Critic reviews are not available for Flugratten PC yet”). The Games-Guide press release is the only primary source of “buzz,” framing it as a quirky, family-friendly holiday release. Its collection stats on MobyGames are telling: as of the latest data, it is “Collected By” only 2 players. This is an astonishingly low number for a commercially released title, placing it among the most obscure entries in the database. On platforms like RAWG and MyAbandonware, it has “Not rated yet” and “no comment nor review,” respectively.

Its legacy is one of profound obscurity and cult curiosity. A Reddit post from 2014 asks, “Does anyone remember a game for windows 95 back in the day where you shoot pigeons??”, a description that fits Flugratten‘s gameplay but misremembers the era (it was 2006, not 95). This post itself demonstrates how the game flickered in the collective memory as a bizarre, half-remembered experience. Its availability on abandonware sites (Old Games Download, MyAbandonware) and the existence of a v1.1 patch on the latter confirm its commercial lifecycle is complete; it is now preserved only by archivists and the curious.

Its influence on the industry is negligible to non-existent. It did not spawn a genre. However, it serves as a fascinating data point in two niches:

1. The German/Speaking-European Casual Game: It predates the mobile boom’s casual domination, attempting a quirky, location-based casual experience for the PC retail market.

2. The Absurdist Arcade Shooter: It shares DNA with the “so-bad-it’s-good” or “weird-for-weird’s-sake” niche later populated by titles like Goat Simulator in spirit, though lacking the procedural generation and intentional surrealism. Its legacy is a “what were they thinking?” footnote, a testament to the sheer diversity of ideas that can get funded, developed, and physically shipped.

Conclusion: The Monument Outlasts the Mess

Flugratten is not a good game by any conventional critical metric. It lacks the narrative heft, mechanical complexity, or technical prowess to be considered great. Its reception was minimal, and its impact vanished with its short retail run. Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to ignore its value as a cultural fossil. It is a perfect encapsulation of a specific developer’s whimsy at a specific time: a Hamburg studio in 2006 using a capable but unexceptional 3D engine to simulate a pan-European war on bird excrement with picnic food. The ambition is palpable in the credits—49 people, custom fonts from Ray Larabie (a legendary typographer in gaming), detailed sound design, ragdoll physics. The vision was to build a complete, funny, polished world.

In the end, Flugratten is the digital equivalent of a bizarre, hand-crafted souvenir from a European city—strange, slightly nonsensical, but memorably specific. The monuments it tasked players to protect—the Brandenburg Gate, the canals of Venice—are timeless. Flugratten, the game, is not. It is a temporary, silly, and utterly forgotten siege against a timeless enemy. Its final, ironic verdict is that the pigeons of history have won, leaving behind only the faintest, most curious stain on the archive. It stands not as a classic, but as a sincere, strange, and supremely forgettable monument to the idea that any gameplay premise, no matter how ludicrous, can be built, shipped, and eventually abandoned to the digital soil from which it came.