- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Developer: Arch D. Robison

- Genre: Action, Educational

- Perspective: Abstract

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Mouse control, Pattern recognition, Wave-based

- Setting: Abstract

- Average Score: 85/100

Description

Frequon Invaders is an abstract action-educational game where players defend against invading Frequons by interpreting colorful wave patterns in a two-dimensional Fourier space. Instead of seeing enemies directly, players detect dark bands that reveal positions, moving the mouse to destroy them before they reach the bottom. With a meditative pacing and focus on math/logic, difficulty increases through more complex patterns and limited radar, challenging players to achieve high scores in this unique wave-based take on Space Invaders.

Frequon Invaders Reviews & Reception

homeoftheunderdogs.net (85/100): It is fun, original, and strangely addictive once you get used to looking at colored waves.

goldenageofgames.com : It is fun, original, and strangely addictive once you get used to looking at colored waves.

Frequon Invaders: A Review of a Mathematical Revolution in a 10KB Package

Introduction: The Invaders That Defy Space and Time

In the vast museum of video game history, most titles sit comfortably within recognizable genres, refining established mechanics or pushing graphical boundaries. Frequon Invaders, released in 2002 by a solo developer, Arch D. Robison, stands utterly alone. It is not merely a Space Invaders clone; it is a profound, playful, and brutally difficult interrogation of what a game is. Its core mechanic—shooting enemies not by targeting pixels in Cartesian space, but by achieving destructive interference with their wave patterns in a two-dimensional Fourier domain—is a concept so radical it feels more like an interactive mathematics thesis than a traditional game. This review will argue that Frequon Invaders is a landmark of “conceptual game design,” a brilliant synthesis of educational purpose and austere, meditative gameplay that prioritizes the cultivation of a non-intuitive spatial intuition over any conventional sense of fun. Its legacy is not in imitation, but in its unwavering proof that a game’s rules can be derived from pure mathematical transformation, creating a unique cognitive experience that has, against all odds, remained compelling for over two decades.

Development History & Context: The Solo Programmer’s Edifice

The Creator and the Constraints:

Frequon Invaders is the work of Arch D. Robison, a developer whose professional background is hinted at by the game’s technical sophistication—likely in scientific computing or engineering. The game was conceived and built in near-total obscurity, a freeware project distributed from a personal website (Blonzonics.us). Its development spanned at least a decade, with the seminal Macintosh version appearing in 2001 (or 2002, per MobyGames) and a significantly updated Windows version, 2.2, arriving much later, rewritten in the Go programming language.

The technological context is defined by extreme optimization. Robison was not working with a AAA engine but was Instead writing hand-vectorized SSE (Streaming SIMD Extensions) assembly code to power the game’s core: the Hyper Fourier Transform (HFT). This was a custom algorithm designed to compute the 2D Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) for a sparse set of points (the player and the “Frequons”) in O(N²) time. This is asymptotically slower than an FFT’s O(N² log N), but crucially, it avoids the “all-to-all” data exchange that hogs memory bandwidth. The HFT’s computation is highly localized, allowing it to run almost entirely within the processor’s L1 cache—a critical optimization for smooth real-time performance on single-core systems of the early 2000s. The very act of playing the game, therefore, was a benchmark for one’s CPU’s single-threaded mathematical throughput.

The gaming landscape of 2001-2002 was dominated by 3D accelerations (PS2, Xbox, GameCube) and polished 2D independents. Frequon Invaders was an anachronism, a zen-like, mathematically-authored artifact that flew under the radar of mainstream press but found its audience in niche communities like Home of the Underdogs (which rated it 8.5/10) and academic circles interested in serious games. Its business model as pure freeware ensured its preservation but guaranteed zero commercial impact, cementing its status as a passion project first and a product second.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: An Invasion of Pure Form

Narrative in Frequon Invaders is almost entirely absent, yet its thematic core is deafeningly loud. The “plot” is the most conventional Space Invaders trope: “The Frequons are invading! Destroy them before they reach the bottom.” There are no characters, no dialogue, no setting lore. The narrative is purely diegetic to the mathematical system. The “Frequons” are not aliens; they are 2D Kronecker delta functions—point sources—in the spatial domain, which manifest as complex wave patterns in the Fourier domain.

The profound theme is epistemological: the game is about learning to perceive and manipulate a hidden reality. The player-character, a negated Kronecker delta (a “self” with opposite polarity), operates not by moving a spaceship but by moving a waveform in global frequency space. The “invasion” is the descent of these spatial points toward a critical line. Victory is impossible; the game is an endless, losing struggle against entropy, scored only by how many patterns of destructive interference you can create before the waves overwhelm you.

This strips away all narrative pretext to focus on a pure experience of system comprehension. The “story” is the player’s own journey from utter confusion (“unless you dream in complex exponentials, you may be quite flustered”) to a hard-won, intuitive grasp of the Fourier transform’s visual signature. The game’s true narrative is the triumph of intuition over abstract mathematics, a David-and-Goliath story where the player’s brain is the underdog.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Architecture of Perception

Core Loop & Objective:

The loop is Space Invaders in skeleton: entities descend; you destroy them; they get faster/more numerous; you eventually lose. The revolutionary difference is the representation and control mechanism.

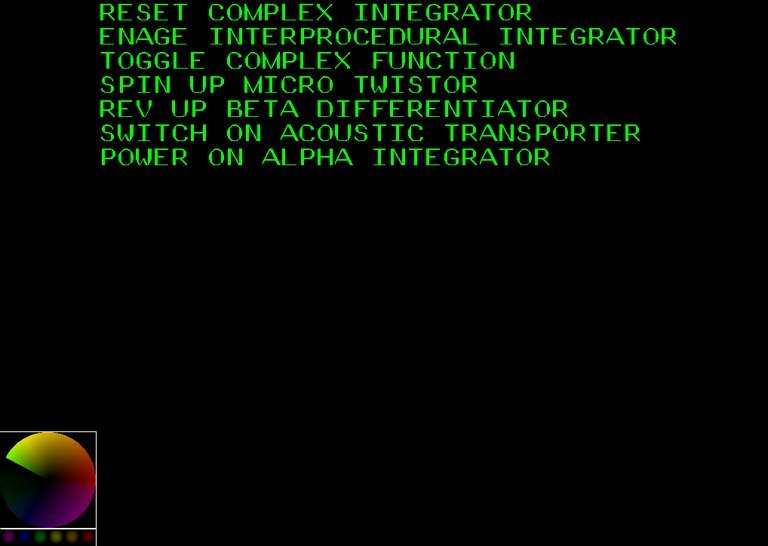

- Representation: You never see “positions.” You see a colorful band of waves (the Fourier domain magnitude/phase). The colors represent the complex numbers on the unit circle, as illustrated by the “Radar” panel. Each Frequon’s spatial location (x,y) corresponds to a specific frequency (u,v) and phase in the Fourier pattern.

- Control: Your mouse cursor controls the position of your “self” (a wave of opposite polarity) in the spatial domain, but its effect is global on the Fourier display. You are not pointing at a pixel; you are setting a global wave function.

The Mechanic of Destruction:

Destruction is achieved through destructive interference. As you move your cursor (your wave source) close to the location corresponding to a Frequon in Fourier space, the bands of color grow darker—the waves are cancelling. Get closer, the dark bands widen. Get precise, the Frequon’s spatial position reveals itself as a small dark circle. Place your cursor exactly on it, and you achieve maximal interference, causing the “Frequon” to explode, its amplitude (shown in the “Amplitude” panel) shrinks to zero, and you score a point.

Progression & “Damage” Systems:

The game’s brilliant difficulty curve is not about adding more enemies first, but about systematically degrading the player’s perceptual information—a metaphorical “damage” to your radar.

- Increased Numbers: Early levels have 1-2 Frequons. Later levels launch up to 10 simultaneously, creating impossibly complex, overlapping wave patterns.

- Information Loss (The “Damage”): This is the masterstroke. Higher levels introduce visual impairments:

- Magnitude-Only: You see only brightness, not color/hue (phase info lost). The world becomes grayscale.

- Color Channel Loss: You lose a primary color (e.g., see only red/green or yellow/blue), losing half the phase information and creating aliasing. The player can be lured to a position diametrically opposite the true Frequon location because the real part of the waveform is symmetric.

- Component-Only: You see only the real component (red/green) or only the imaginary component (yellow/blue) of the complex wave. This creates bizarre perceptual traps—perfect cancellation appears on the display that doesn’t correspond to the true spatial point.

- Display Collapse: The Fourier panel can partially collapse horizontally or vertically, mimicking a failing CRT monitor, further scrambling spatial mapping.

Training Mode as a Sandbox:

The configurable training mode is essential. It allows you to:

* Peek at Frequon locations.

* Set them as Stationary or Moving.

* Control the number of Frequons (up to 13).

* Cycle the Color display (Complex, Real, Imaginary, Magnitude, Phase).

This mode transforms the game from a punishing test into a playful mathematical sandbox. You can create mesmerizing, beautiful wave patterns without pressure, truly learning how spatial shifts affect the Fourier representation.

UI & Feedback:

The UI is ruthlessly functional, divided into four panels: Score (binary, “ultrageek” aesthetic), Radar (color mapping key), Amplitude (ticks showing Frequon strength), and Fourier (the main playfield). Sound is minimal—blips on appearance/destruction—which is perfect, as any music would distract from the visual concentration required. The “thunk” of display collapse is a memorable, synthesized event.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of the Equation

There is no traditional “world.” The “setting” is the Fourier domain itself—a abstract, mathematical plane rendered as vibrant, swirling, interlacing bands of color. The visual direction is defined by the complex-to-color mapping. The default “Complex” mapping uses the full color wheel, creating psychedelic, mandala-like patterns that shift and pulse as you move. It is chaotic yet deeply structured.

The “art” is the real-time rendering of the HFT computation. Its beauty is not in artistically painted assets but in the emergent patterns of interference. A single Frequon creates a clean, radial wave pattern. Two create a Moiré-like interference pattern. Ten create what looks like a vibrant, abstract oil painting. The “Progressive Weirdness” of damage modes alters this aesthetic, desaturating it or slicing it apart, making the world feel broken in a literal, cognitive sense.

Sound design is equally minimalist and purposeful. The additive synthesis for Frequon sounds (with time-reversed death twangs) is a clever, nerdy touch, but its primary function is punctuative—a sparse auditory anchor in an otherwise silent, visually demanding space. The game’s atmosphere is meditative, tense, and intellectually claustrophobic. It is a Zen puzzle of perception.

Reception & Legacy: The Curious Case of the 8.5/10 Niche Masterpiece

Initial Reception:

Given its obscurity, Frequon Invaders had no “critical reception” in the mainstream sense. On MobyGames, it has a Moby Score of n/a and a player average of 4.2/5 from a single rating—statistically negligible. Its true reception is captured by Home of the Underdogs’ 8.5/10 from 18 votes and its passionate cult following among mathematically-inclined players and educators. The consensus, perfectly summarized by HOTUD, is that it is “the most unique Space Invaders clone ever,” “strangely addictive once you get used to it,” but with an “extremely high geekiness quotient” that is a barrier to entry.

Evolution of Reputation:

Its reputation has grown as a legendary oddity. It is frequently cited in discussions of:

1. Serious/Educational Games: It is a perfect, self-contained “edugame” for teaching Fourier Transform intuition. GameClassification.com explicitly tags it for domains in “Education” and “Scientific Research” and audiences from ages 8-25.

2. Abstract/Experimental Game Design: It stands alongside titles like Liquid War or CHAMP Invaders as a game whose mechanics are an pure, playable concept.

3. Technical Showcases: Robison’s technical article, “Dependence Breaking Speeds Up Frequon Invaders,” and the HFT’s use in the game itself have given it a footnote status in discussions of game engine optimization and real-time signal processing.

Influence:

Its direct influence on subsequent commercial games is virtually zero. It is too singular, too tied to a specific mathematical concept. Its legacy is inspirational and cautionary. It proves a game can be built around a single, dense academic idea and still be engaging (to a specific audience). It also demonstrates the limits of such focus—without conventional rewards, narrative, or even clear visual feedback, its audience will always be tiny. It is the ultimate “for gamer scientists” title.

Conclusion: The Undiscovered Country of Play

Frequon Invaders is a paradox: a game that is frustratingly impenetrable yet intellectually rewarding; visually stunning yet functionally barren; historically insignificant in sales yet monumental in concept. Arch D. Robison did not set out to make the next Space Invaders. He set out to make the Fourier Transform playable, and in doing so, he created a new kind of game object—a mathematical toy, a perceptual training simulator, and a meditative loss.

Its place in video game history is not on the mainstream timeline but in a side chamber of the museum, labeled “Games as Theorem.” It is a testament to the medium’s capacity to embody complex ideas as interactive experiences. To play Frequon Invaders is to engage in a form of cognitivearte, to literally dream in complex exponentials for a few minutes. It will never be popular, but for those who meet its daunting challenge, it offers a transformative insight: that behind the chaotic swirl of colors lies an elegant, learnable order. In the end, the game’s true victory is not in the high score, but in the moment the player finally sees—not with their eyes, but with their newly-forged intuition—the hidden location of a Frequon, and understands the beautiful, invisible mathematics that has been there all along.

Final Verdict: A groundbreaking, impenetrable, and beautiful failure as a conventional game; a perfect, timeless success as an interactive mathematical thought experiment. * (5/5) as a conceptual masterpiece; ★★ (2/5) as a widely accessible entertainment product. Its score depends entirely on which game you thought you were buying a ticket for.