- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Developer: Christopher Christensen, Jay Geertsen, John Rotenstein, Philippe Basciano

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Falling block puzzle, Real-time

- Average Score: 58/100

Description

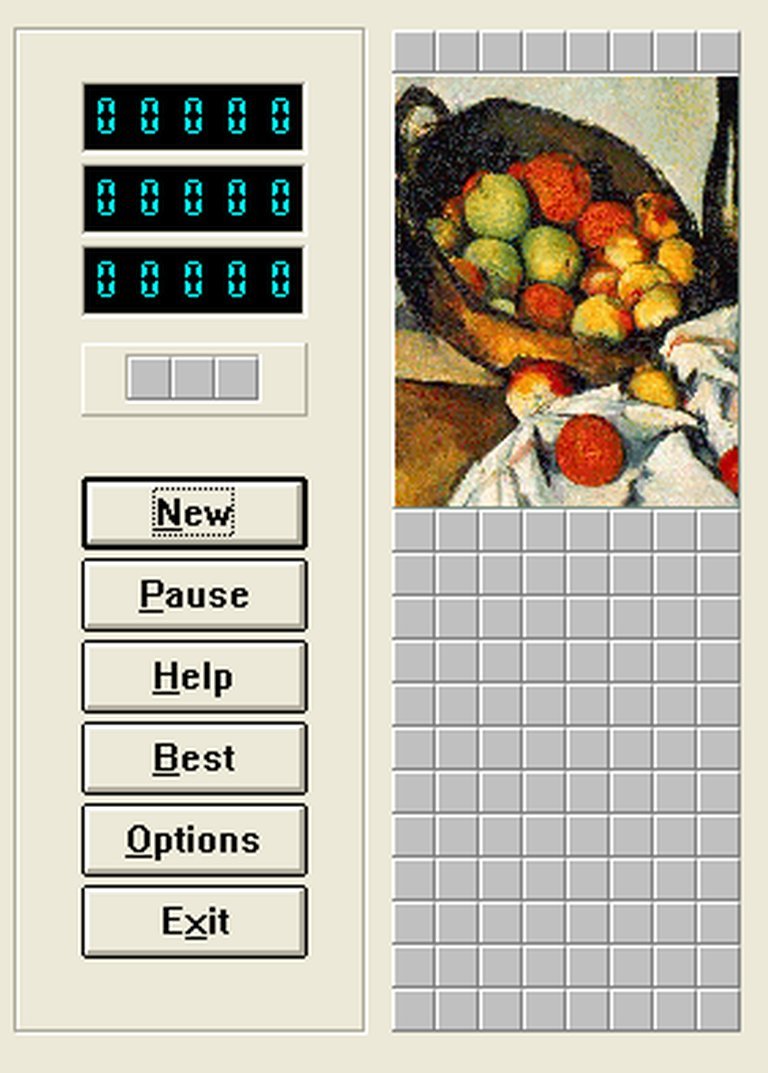

Fructus is a 1995 freeware falling block puzzle game for Windows, inspired by Columns, where players customize starting levels and row lengths before manipulating descending rows of three random fruits—cherries, strawberries, watermelons, apples, grapefruits, plums—to form matches of three or more identical fruits horizontally, vertically, or diagonally at the bottom of the playfield. Clearing matches earns points, drops fruits above, and advances through nine increasingly faster levels, with red stars destroying fruits on impact, and an optional plain square-based mode available.

Where to Buy Fructus

PC

Fructus Free Download

PC

Fructus: Review

Introduction

In the pixelated dawn of personal computing gaming, where block-dropping puzzles reigned supreme alongside the likes of Tetris and Sega’s addictive Columns, emerges Fructus—a humble, fruit-flavored homage that captures the essence of real-time matching mania. Released in February 1995 for Windows 3.x (16-bit), this freeware gem by Philippe Basciano invites players into a cascade of cherries, strawberries, and watermelons, challenging them to stack, swap, and explode their way to high scores across nine escalating levels of frenzy. As a historian of digital pastimes, I argue that Fructus exemplifies the DIY spirit of mid-90s shareware culture: a technically proficient clone that democratized arcade perfection for the emerging Windows masses, even if its lack of bold innovation relegates it to a nostalgic footnote rather than a genre-defining masterpiece.

Development History & Context

Fructus was the brainchild of solo developer Philippe Basciano, a programmer whose modest portfolio spans a handful of Windows-era titles. Credited explicitly for “Fructus ver. 2.0 for Windows,” Basciano built directly atop a lineage of Columns ports, acknowledging John Rotenstein’s COLUMNS for Windows, which itself stemmed from Christopher Christensen’s COLUMNS for Macintosh and Jay Geertsen’s foundational XCOLUMNS. This chain of attributions underscores the game’s roots in Sega’s 1990 Genesis blockbuster Columns, a real-time falling-block puzzle that popularized vertical jewel-matching with rotatable triplets. A special thanks goes to Jerry J. Shekhel for bitmaps sourced from Chomp for Windows version 1.1, highlighting the collaborative, resource-sharing ethos of early PC indie development.

The mid-1990s marked a pivotal shift in PC gaming. Windows 3.1 dominated desktops, but graphical limitations—low-res 16-color displays, keyboard-only input, and no hardware acceleration—constrained ambitions. Shareware flooded bulletin boards and magazines like PC Gamer, with puzzle games thriving due to their low system requirements and addictive loops. Fructus launched amid this boom, just before Windows 95’s July 1995 debut promised richer multimedia. A 1996 Windows (32-bit) port followed, adapting to the new OS. As freeware/public domain software, it epitomized the era’s open-source precursors, distributable via floppy disks or early internet archives like the Internet Archive, where it’s preserved today for emulation via DOSBox. Technologically, it squeezed maximum playability from modest specs: real-time action on 386/486 machines, with customizable options mitigating hardware variance. In a landscape dominated by ports of console hits (Tetris, Dr. Mario) and emerging titles like Hexen, Fructus carved a niche as accessible, no-frills entertainment for office workers and students alike.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Fructus eschews traditional storytelling entirely, a deliberate choice befitting its arcade heritage. There are no characters, cutscenes, or lore—no plucky fruit farmer battling a produce apocalypse, no anthropomorphic cherries with backstories. Instead, the “narrative” unfolds through pure mechanical progression: a silent ascent from level 1’s leisurely drops to level 9’s blistering pace, punctuated by score milestones and explosive clearances. This absence of plot amplifies its thematic purity: the Sisyphean struggle against entropy, where colorful abundance threatens to overwhelm a finite well of chaos.

Thematically, Fructus revels in abundance and impermanence. Fruits—symbols of nature’s bounty (cherry for sweetness, watermelon for heft, plum for subtlety)—represent life’s fleeting pleasures, matched and vanished in bursts of digital satisfaction. Red “stars” introduce serendipity, empty-column bombs that cascade destruction, evoking karmic rewards for strategic voids. The optional square-based mode strips away the fruity veneer, revealing a Platonic ideal of abstraction versus whimsy. Dialogue? Nonexistent beyond option menus. Yet this minimalism fosters emergent drama: each near-miss stack builds tension, each combo a triumphant release. In an era of narrative-heavy adventures like Myst, Fructus reminds us that puzzles need no words to grip the soul, theming compulsion through compulsion itself.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Fructus refines Columns‘ iconic loop: triplets (default three fruits, customizable to eight per row) descend in real-time from the top of a vertical playfield. Players manipulate their left-right-up-down order via keyboard (arrow keys implied), dropping them to form lines of three or more identical fruits horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Matches vanish with satisfying physics—overlying pieces tumble down—awarding points scaled by combo size and speed. Score thresholds advance nine levels, ramping fall velocity for escalating peril. The game ends when blocks hit the third row from the top, a tight 12-row field demanding foresight.

Innovations are subtle but smart: pre-game options for starting level (1-9) and match threshold (3-8) enable accessibility and challenge tuning, rare for 1995 freeware. Red stars spawn in empty columns, detonating on impact to clear swaths of fruits for bonus points, injecting luck-based excitement. The toggleable square mode offers purist Columns play sans fruits, broadening appeal. UI is spartan—score, level, next piece preview—but intuitive, with no tutorials needed for veterans. Flaws emerge in longevity: no endless mode, no leaderboards, no multiplayer. Progression feels linear, reliant on pattern recognition over deep strategy. Controls, keyboard-bound, suit quick sessions but lack mouse support, a missed opportunity post-Windows 95. Still, the loop mesmerizes: anticipate drops, cycle permutations (e.g., cherry-strawberry-watermelon rotates fluidly), chain reactions for multipliers. It’s flawlessly executed clone-craft, addictive in bursts but unforgiving at higher speeds.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Fructus‘ “world” is a stark, grid-bound void—a black expanse framed by simple borders, evoking Columns‘ abstract elegance over bombast. No sprawling realms or lore-laden hubs; the playfield is the universe, populated solely by falling produce. Visual direction leans whimsical: six vivid fruits (cherry’s red gleam, watermelon’s green stripes, grapefruit’s bumpy pink, apple’s sheen, strawberry’s seeds, plum’s deep purple) pop against the monochrome field, sourced from Chomp‘s bitmaps for charming, low-poly authenticity. Stars add explosive flair, pixel bursts clearing the board. Raster graphics (side-view perspective) scale to 640×480, windowed for multitasking—perfect for 90s desktops.

Atmosphere builds through motion: languid early drops yield to frantic cascades, heightening claustrophobia as stacks rise. Art contributes immersion subtly—fruits’ differentiation aids quick scanning, diagonals encourage spatial creativity. Sound design, inferred from era norms and emulation archives, likely features basic MIDI beeps: plinks for drops, bloops for matches, accelerating tempo per level. No voice, music, or effects libraries noted, keeping it lightweight. These elements coalesce into hypnotic minimalism: visuals entice, sounds punctuate, fostering “just one more game” flow. In Windows 3.x’s beige desktop sea, Fructus was a juicy portal to focused euphoria.

Reception & Legacy

Launch reception for Fructus was ghostly—freeware obscurity yielded no critic reviews on MobyGames, only two player ratings averaging 2.8/5, suggesting niche appeal marred by clonetude. No sales figures (being free), but low collection counts (2-3 players on MobyGames/Grouvee) reflect its underground status. Shareware boards likely buzzed modestly, preserved today on Archive.org, MyAbandonware, and UVList as emulatable relics.

Legacy endures as a Columns variant in the “Columns groups” taxonomy, influencing no majors but epitomizing PC puzzle proliferation. Contemporaries like Gelules (1994), BeeTris (1996) echoed its formula amid PGA Tour 96 and Flight Simulator giants. Post-2000, it faded, but emulation revivals highlight its purity. A 2021 Steam title “Fructus” (unrelated, 60/100 score) nods to name confusion. Industrially, it underscores shareware’s role in skill refinement—Tetris clones honed mechanics for Puzzle Bobble, Puyo Puyo. Culturally, it’s a time capsule: democratizing joy for pre-broadband gamers, proving elegance trumps flash.

Conclusion

Fructus is no revolutionary fruit basket—it’s a loving, laser-focused Columns tribute, excelling in tight mechanics, customization, and era-appropriate charm while stumbling on originality and depth. Philippe Basciano’s handiwork captures 1995’s DIY zenith, a freeware beacon for keyboard-tapping addicts. In video game history, it claims a quiet pedestal among puzzle progenitors: essential for genre scholars, nostalgic for Windows 3.x survivors, skippable for moderns. Verdict: 7/10—a ripe, replayable relic demanding emulation to savor its sweet simplicity. Fire up DOSBox; let the fruits fall.