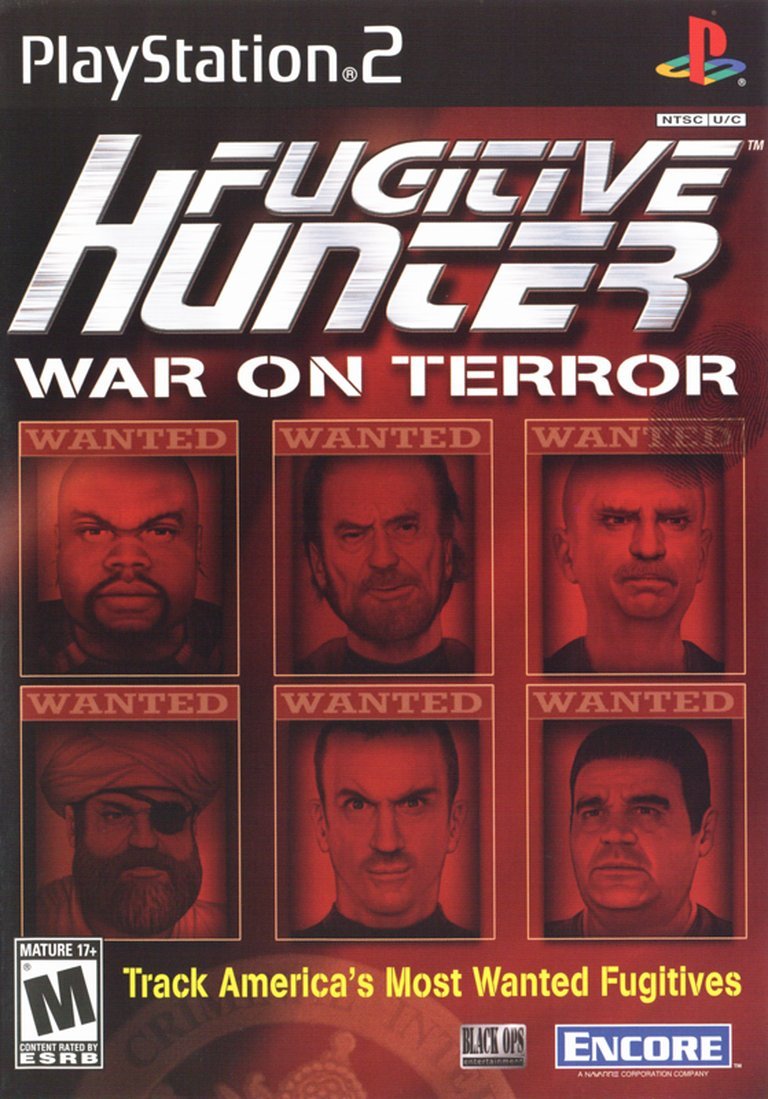

- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: PlayStation 2, Windows

- Publisher: Encore, Inc., Noviy Disk, Play It Ltd.

- Developer: Black Ops Entertainment, LLC

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Average Score: 36/100

Description

Fugitive Hunter: War on Terror is a first-person shooter where players assume the role of bounty hunter Jake Seaver, tasked with tracking down high-profile criminals inspired by real-world fugitives. Developed by Black Ops Entertainment, the game blends cinematic storytelling, motion-captured animations, and customizable weapons to simulate high-stakes manhunts drawn from FBI Most Wanted List concepts. Released in 2003 for PlayStation 2 and Windows, it combines action-packed shootouts with dramatic confrontations against notorious targets.

Gameplay Videos

Fugitive Hunter: War on Terror Cracks & Fixes

Fugitive Hunter: War on Terror Guides & Walkthroughs

Fugitive Hunter: War on Terror Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (35/100): It was mainly received negatively due to its dated graphics and uninspired boss battles.

metacritic.com (35/100): It’s a short game with bland mechanics, repetitive levels, and almost zero replay value, and that’s not even taking into account the total absurdity of getting into a fistfight with Osama Bin Laden.

Fugitive Hunter: War on Terror Cheats & Codes

PlayStation 1

Enter the first code at the title screen. Enter the second code by pausing the game during the Afghanistan-Pakistan Border mission.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, SQUARE, SQUARE, SQUARE, SQUARE | Unlocks cheats in the Special Features menu. |

| CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, SQUARE, SQUARE, SQUARE, R2 | Causes every 6th enemy to be Bin Laden. |

PlayStation 2

Enter the first code at the title screen. Enter the second code by pausing the game during the Afghanistan-Pakistan Border mission.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, SQUARE, SQUARE, SQUARE, SQUARE | Unlocks cheats in the Special Features menu. |

| CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, SQUARE, SQUARE, SQUARE | Causes enemies to appear as Bin Laden. |

PlayStation 2 (PAL)

Enter the first code at the title screen. Enter the second code by pausing the game during the Afghanistan-Pakistan Border mission.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, SQUARE, SQUARE, SQUARE, SQUARE | Unlocks cheats in the Special Features menu. |

| CIRCLE, CIRCLE, CIRCLE, SQUARE, SQUARE, SQUARE, R2 | Causes enemies to appear as Bin Laden. |

Fugitive Hunter: War on Terror: Review

Introduction

In the annals of gaming history, few titles have courted controversy and critical derision as fervently as Fugitive Hunter: War on Terror (2003). Released at the height of post-9/11 geopolitical tensions, this PlayStation 2 and PC first-person shooter attempted to monetize nationalistic fervor by casting players as bounty hunter Jake Seaver, tasked with capturing real-world terrorists like Osama bin Laden. Developed by Black Ops Entertainment and published by Encore, the game became a lightning rod for debates about taste, exploitation, and the intersection of politics and entertainment. This review argues that Fugitive Hunter is a fascinating cultural artifact—a poorly executed, ethically dubious game whose legacy lies not in its gameplay but in its reflection of early-2000s jingoism and the pitfalls of “edutainment” gone awry.

Development History & Context

Studio Vision and Constraints

Black Ops Entertainment—a studio best known for The X-Files: Resist or Serve and Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines—began developing Fugitive Hunter in 1998 under the working title America’s 10 Most Wanted. Originally intended as a crime thriller inspired by the FBI’s Most Wanted list, the project underwent a drastic shift after the September 11 attacks. According to behind-the-scenes footage, a New York City level near the World Trade Center was scrapped, and the narrative pivoted to focus exclusively on Islamist terrorists. This opportunistic retooling aimed to capitalize on public anger, with lead designer John Botti stating the team sought to create a “cinematic” experience mirroring real-world manhunts.

Technologically, the game was hamstrung by its budget. Built on aging middleware like Bink Video, it lacked the polish of contemporaries such as Halo or Call of Duty. The PlayStation 2’s hardware limitations exacerbated issues: rudimentary motion-captured animations and recycled assets resulted in a title that felt dated at launch.

The Gaming Landscape

Fugitive Hunter debuted amid a flood of post-9/11 military shooters, but its blatant exploitation of real-world trauma set it apart. While games like Conflict: Desert Storm fictionalized Middle Eastern conflicts, Fugitive Hunter namedropped bin Laden and Saddam Hussein (the latter only in the European release), blurring lines between entertainment and propaganda. Initially set for a June 2003 release under Atari’s Infogrames label, publisher cold feet over its tone led Encore to acquire it for a November 2003 launch at a budget price of $19.99—a tacit admission of its B-tier status.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot and Characters

Players assume the role of Jake Seaver, a CIFR (Criminal Interdiction and Fugitive Recovery) agent haunted by a failed 1999 Afghanistan mission. Across 11 levels spanning Miami, Pakistan, and Paris, Seaver hunts fugitives loosely tied to Al-Qaeda, culminating in a fistfight with bin Laden himself. The narrative is a threadbare excuse for action, stitched together with pre-mission briefings and cutscenes featuring stiff voice acting. Seaver’s dialogue oscillates between macho clichés (“Justice is coming!”) and unintentional self-parody, undermining any attempt at gravitas.

Themes and Ethical Quandaries

Fugitive Hunter’s thematic core is unapologetically jingoistic. By framing global counterterrorism as an arcade-style shooting gallery, it reduces complex geopolitical strife to a simplistic “us vs. them” binary. Critics lambasted its depiction of Middle Eastern enemies as turban-wearing stereotypes, while the inclusion of bin Laden—still at large in 2003—felt exploitative. The game’s nadir arrives in its final act, where Seaver discards his arsenal to brawl bin Laden in a slapstick melee minigame, trivializing real-world trauma.

European versions added surreal tweaks: Saddam Hussein replaced a fictional cartel boss, and the manual listed Taliban leader Mullah Omar, though he never appeared in-game. These changes underscored the developers’ cynical flexibility in tailoring propaganda to regional markets.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loops

As a first-person shooter, Fugitive Hunter is functional but uninspired. Players navigate linear levels filled with respawning enemies, collecting weapons like shotguns, flamethrowers, and grenade launchers. A rudimentary upgrade system allows minor modifications (e.g., scopes), but customization lacks depth. The shooting mechanics are serviceable yet hobbled by:

- Poor Hit Detection: Bullets often phase through enemies.

- Repetitive Objectives: Missions devolve into “kill everyone” tasks.

- AI Glitches: Foes get stuck on geometry or ignore the player entirely.

The Infamous Hand-to-Hand Combat

Each level culminates in a boss fight that shifts to third-person perspective. Using canned combos and dodges, players pummel fugitives into submission—a baffling design choice that clashes with the FPS format. Reviewers derided these sequences as “goofy” (GameSpy) and “an embarrassment” (G4 TV), noting that disarmingly bin Laden via fisticuffs strained credulity beyond breaking point.

UI and Progression

The HUD is barebones, with a health bar and ammo counter. No checkpoint system exists; dying forces replaying entire levels. With only 5-6 hours of content and no multiplayer, replay value is nonexistent.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design

Fugitive Hunter’s graphics were outdated even in 2003. Character models are blocky, textures are muddy, and environments like Afghan caves or Parisian streets feel barren and repetitive. Animation is stiff, particularly during cutscenes where lip-syncing is nonexistent. The art direction leans into realism but lacks the budget to sell it, resulting in a drab, unconvincing world.

Sound Design

The game’s audio is a mixed bag. Tommy Tallarico’s score apes Hollywood action tropes with generic orchestral swells, while gunfire and explosions lack punch. Voice acting is laughably bad—Seaver’s growls evoke a direct-to-video action hero. Oddly, the European version features tracks by UK garage group So Solid Crew, juxtaposing gritty terrorism themes with early-2000s club beats.

Atmosphere

Attempts at tension—like stealth segments or climbing sequences—fall flat due to clumsy controls. The lack of environmental storytelling (e.g., documents intel) renders settings like terrorist camps hollow and interchangeable.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Panning

Fugitive Hunter was eviscerated upon release:

- Metascore: 35/100 (based on 15 reviews).

- GameSpot (3.4/10): “A short game with bland mechanics, repetitive levels, and almost zero replay value.”

- IGN (3.3/10): “The appeal of going after bin Laden drives this title—but even that distinction has faded.”

- Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine (1/5): “Proof positive that the terrorists are winning.”

Critics universally mocked its tone-deaf premise, clunky combat, and technical woes. It later “earned” a spot on GameSpot’s “Top 10 Most Frightfully Bad Games of 2004.”

Commercial Performance

The game sold poorly—VGChartz estimates 150,000 copies worldwide—and swiftly disappeared into bargain bins. Encore later bundled it with Mob Rule, a Constructor spin-off, to salvage value.

Cultural Impact

Though Fugitive Hunter influenced no sequels or genres, its legacy persists as a case study in bad taste. It presaged later exploitative titles like Kuma\War (2004), which similarly commodified terrorism, but lacked even their ironic charm. Modern retrospectives view it as a “cultural Chernobyl” (Press Start Gaming)—a reminder of how games can trivialize real-world pain for profit.

Conclusion

Fugitive Hunter: War on Terror is not merely a bad game; it is a morally fraught artifact of post-9/11 America. Its sloppy mechanics, dated presentation, and cynical appropriation of geopolitical trauma render it unplayable by modern standards. Yet, as a historical document, it offers invaluable insights into early-2000s media culture—where fear and nationalism could be packaged as entertainment. While worth studying for scholars of game ethics, it remains a stain on the medium, a cautionary tale of what happens when artistry is sacrificed at the altar of opportunism. In the pantheon of video games, Fugitive Hunter is less a shooter than a shooting star—bright, brief, and best forgotten.