- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Radix

- Developer: Radix

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Direct control, Voice control

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

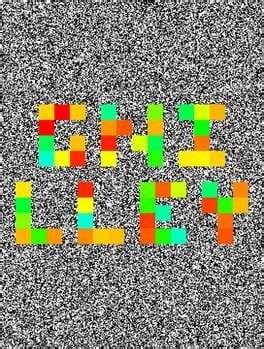

GNILLEY is a freeware fantasy action game featuring retro graphics inspired by The Legend of Zelda. Players navigate a hostile world using voice commands – yelling into a microphone to blast through obstacles and damage enemies. The screen shakes and flashes dramatically when the player takes damage, adding chaotic challenge to this unconventional combat and navigation system.

GNILLEY Free Download

GNILLEY: Review

Introduction

In an industry often obsessed with photorealistic graphics and sprawling open worlds, GNILLEY (2010) stands out as a defiantly absurd experiment—a game where screaming into a microphone is not just a mechanic but the entire point. Developed by Glen Forrester for the Sydney Global Game Jam, this freeware oddball repurposes The Legend of Zelda’s iconic sprites into a chaotic stress-relief simulator. While hardly a commercial or critical juggernaut, GNILLEY epitomizes the creative bravado of indie jams, leveraging voice control in ways that are equal parts hilarious, abrasive, and oddly therapeutic. This review argues that GNILLEY deserves recognition not as a polished gem but as a cult artifact of gaming’s experimental fringe—a reminder that fun can emerge from the simplest, loudest ideas.

Development History & Context

Origins in the Global Game Jam

GNILLEY was born during the 2010 Global Game Jam, an event celebrating rapid prototyping and unconventional ideas. Forrester’s initial concept—a game about pitch and color—morphed into something far more primal: a tech demo demanding players yell into their microphones to progress. Developed under the studio name Radix, the game was crafted in days, embracing the Jam’s ethos of creative constraint.

Technological Constraints & Innovation

In 2010, voice recognition in games was still nascent. Titles like SEAMAN (1999) and Hey You, Pikachu! (1998) had experimented with microphone inputs, but GNILLEY stripped the concept to its bare essentials. With no budget for original assets, Forrester borrowed Zelda’s visuals, creating a dissonant contrast between Nintendo’s wholesome nostalgia and the game’s cathartic mayhem. The result was a lo-fi triumph, relying on Windows’ basic microphone APIs to transform raw volume into gameplay.

The Indie Landscape

GNILLEY debuted amid a surge of indie experimentation. Games like Octodad and QWOP were redefining “fun” through janky physics and absurd premises. While not as polished as its contemporaries, GNILLEY shared their DNA, prioritizing novel interactivity over technical polish.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot? What Plot?

GNILLEY has no story—no princess to rescue, no quest to fulfill. The player controls a Zelda-esque hero navigating maze-like environments, but narrative context is irrelevant. The game’s “plot” is purely meta: it’s about you, standing in your room, screaming at your computer until your throat hurts.

Themes of Catharsis & Control

Thematically, GNILLEY weaponizes frustration. By channeling real-world aggression into in-game power, it becomes a digital stress ball. The act of yelling—often dismissed as childish—is gamified, transforming the player into both protagonist and antagonist. This duality reflects a broader commentary on gaming’s potential for raw, physical expression, untethered from traditional inputs like buttons or joysticks.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Scream to Win

The gameplay revolves around two actions:

1. Yell to Attack: Hostile creatures disintegrate when assaulted with sufficient decibels.

2. Yell to Navigate: Obstacles vanish temporarily when shouted at, forcing players to sustain volume to progress.

Innovation & Flaws

While revolutionary in concept, GNILLEY’s execution is erratic:

– Accessibility Issues: Players with speech impairments or quiet environments are locked out.

– Sensor Limitations: Cheap microphones often fail to register volume consistently.

– Repetition: The novelty wears thin after 10 minutes, with no progression systems or varied challenges.

UI & Feedback

The screen shakes and flashes when the player takes damage, mimicking the disorientation of being “hurt.” While effective thematically, this can cause literal headaches—a risky design choice.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Aesthetic Nostalgia

GNILLEY’s world is a collage of Zelda’s 8-bit landscapes, repurposed without context. The familiarity of Hyrule’s tilesets clashes deliciously with the game’s anarchic premise, creating a surreal dissonance.

Sound Design

There is no soundtrack—only the player’s voice and crude sound effects. enemies explode with a comedic pop, and obstacles squeak when dispelled. This minimalism amplifies the focus on vocal participation, making every yell feel consequential.

Reception & Legacy

Initial Reaction

Coverage was sparse but amused. Destructoid likened it to “a non-episode of Dragon Ball Z,” while Rock Paper Shotgun simply called it “the best thing ever.” Its freeware status limited commercial reach, but it gained cult traction via Let’s Play videos, notably by PewDiePie.

Long-Term Influence

GNILLEY’s legacy lies in its audacity. It predated the voice-controlled craze of Skyrim’s “Fus Ro Dah” shouts and Twitch Plays Pokémon, proving that even absurd mechanics could inspire innovation. Modern titles like Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes owe a debt to its emphasis on physicality and collaboration.

Conclusion

GNILLEY is not a “good” game by conventional metrics. It’s repetitive, inaccessible, and technically crude. Yet as a piece of interactive art, it’s unforgettable—a screaming manifesto against design orthodoxy. For a few glorious minutes, it turns players into chaotic gods, demanding nothing but their loudest, dumbest instincts. In an era where games often prioritize cinematic gravitas, GNILLEY remains a vital counterpoint: proof that sometimes, all we need is to yell at the void and laugh at the echoes.

Final Verdict: A flawed but foundational text in indie game history—best experienced once, at maximum volume, with neighbors warned in advance.