- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: 3DO, PC-98, PC-FX, PlayStation, SEGA Saturn, TurboGrafx CD, Windows

- Publisher: GameBank Corp., HOKUBU Communication & Industrial Co.,Ltd., Japan Home Video Co. Ltd., Mixx Entertainment, NEC Home Electronics, Ltd., Riverhill Soft Inc.

- Developer: Headroom, TENKY Co. Ltd.

- Genre: Simulation

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Business simulation, Managerial

- Setting: High school

- Average Score: 95/100

Description

Graduation for Windows 95 is a Japanese anime-style life simulation game where players take on the role of a homeroom teacher responsible for guiding five unique high school girls through their final year. By managing their class schedules, offering guidance counseling, interfering in their weekend plans, and ensuring they stay out of trouble, players’ choices determine whether the girls graduate, pursue successful futures, or develop grudges, potentially leading to praise from the boss or dismissal.

Graduation for Windows 95 Guides & Walkthroughs

Graduation for Windows 95 Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : Satisfying balance between strategy and narrative with high replayability.

Graduation for Windows 95: Review

Introduction

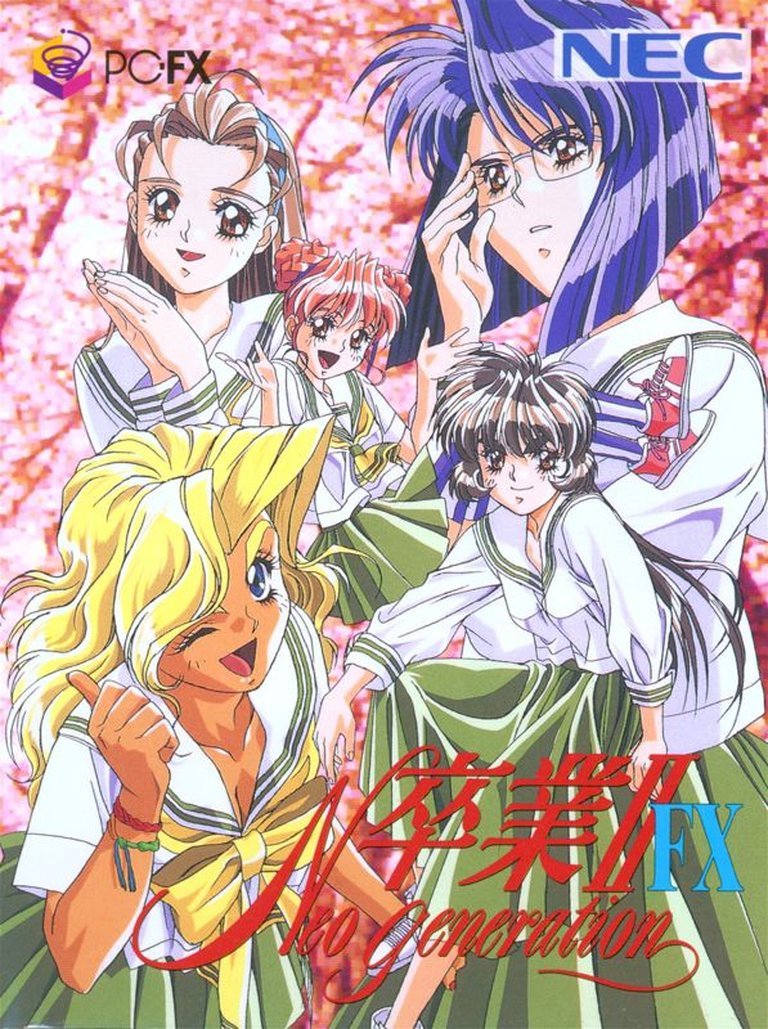

Imagine stepping into the shoes of a beleaguered homeroom teacher at a Japanese all-girls high school, juggling the dreams, dramas, and delinquencies of five seniors on the cusp of adulthood—your every decision a tightrope walk between academic triumph and total catastrophe. Graduation for Windows 95, the 1997 English-localized port of Headroom’s 1994 PC-98 gem Sotsugyō II: Neo Generation, isn’t just a quirky life-sim; it’s a pioneering artifact of the anime-infused simulation genre that dared to bring interactive mentorship to Western audiences. Billed by publisher Mixx Entertainment as “the first anime game to hit American shores,” this title predates the mainstream explosion of raising sims like Princess Maker in the West and captures the essence of mid-90s Japanese PC gaming. My thesis: Graduation endures as a foundational work in managerial life-sims, blending heartfelt character drama with strategic depth to offer a surprisingly mature meditation on guidance, growth, and the butterfly effects of choice—flawed yet profoundly influential in an era dominated by shooters and RPGs.

Development History & Context

Developed by the boutique studio Headroom, Sotsugyō II: Neo Generation launched on May 27, 1994, for Japan’s PC-98 platform, a dominant force in the early-90s Japanese PC market known for its robust multimedia capabilities and anime-centric titles. Headroom, a small team specializing in simulation and visual novels, built on the success of the 1992 original Sotsugyō, expanding its scope with a larger cast and more intricate systems. Key credits include scenario writer Hisaya Takabayashi for the branching narratives, CG director Hiroshi Muroki and character designer Hiyoko Kobayashi for the evocative anime art, and a soundtrack helmed by Noriyuki Iwadare (of Lunar fame), Kenichi Ōkuma, and Masaki Tanimoto—composers whose melodic flair elevated the game’s emotional beats.

The development occurred amid technological constraints: PC-98’s 640×400 resolution and limited color palette demanded efficient sprite work and static scenes, while CD-ROM ports to TurboGrafx CD and PC-FX (both late 1994) introduced voice acting and fuller animations, courtesy of collaborators like Two-Five Ltd. for music and Image Works for cutscenes. Riverhillsoft Inc. spearheaded console ports to SEGA Saturn (1995), PlayStation (1995, with a 1999 re-release), and 3DO (1995 via HOKUBU), adapting the game for 16-bit hardware with minimal compromises.

Contextually, 1994 was a transitional year for gaming. Japan’s doujin and PC markets birthed innovative sims amid the 16-bit console wars, with titles like Gainax’s Princess Maker (1991 PC-98) proving “raising sims” viable. Globally, Windows 95’s impending launch promised broader PC accessibility, but anime games were niche imports. Mixx Entertainment’s 1996 Japanese Windows port (as Graduation for Windows 95) and 1997 U.S. release via GameBank Corp. boldly localized it, stripping overt cultural references while preserving its core. Priced affordably (e.g., $11 used PS1 copies today), it navigated era-specific hurdles like low-res UI and no saves in early versions, reflecting a bold push to export Japan’s “life-sim” wave before The Sims popularized the genre.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Graduation unfolds as a serialized drama set at Private Seika Girls’ High School, Class 3-B, where you play the newly assigned homeroom teacher to five distinct seniors. The plot spans a single school year, structured around calendars, exams, and events, culminating in graduation ceremonies that hinge on your interventions. No overarching antagonist exists; conflict arises organically from each girl’s backstory:

- Yumi: The studious overachiever grappling with parental pressure.

- Reika: The rebellious artist tempted by nightlife.

- Kyoko: The shy introvert battling social anxiety.

- Saori: The athletic tomboy facing career uncertainties.

- Mami: The bubbly socialite hiding family woes.

(Names inferred from series lore and promotional materials like the “Graduation Album” CD drama.) Dialogue, penned by Takabayashi, is sharp and reactive—guidance sessions feature branching trees where probing questions reveal insecurities, fostering bonds or resentment. Weekends trigger “event flags”: intervene in arcade visits or late-night parties, and narratives pivot from triumph (top university acceptance) to tragedy (dropout, pregnancy scares, or—infamously—romantic fixation on you, leading to firing).

Thematically, Graduation dissects mentorship’s double edge: empowerment through tailored advice versus overreach breeding dependency. It critiques Japanese exam hell (juken jigoku), emphasizing holistic growth over rote success, with endings spanning elite colleges, jobs, or failures. Subtle anime tropes—mild fanservice like swimsuit events—underscore teen hormones without nudity, subverting hentai expectations. Broader motifs include consequence and agency: poor scheduling tanks grades, ignored counseling spirals into delinquency, mirroring real pedagogical ethics. Multiple paths (dozens per girl, hundreds combined) ensure replayability, with “bad ends” like mass marriage proposals delivering wry humor amid pathos. This narrative density, rare for 1994 sims, prefigures visual novels like Clannad, making Graduation a thematic bridge between sims and story-driven games.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Graduation‘s loop is a masterful managerial sim, distilling teaching into accessible cycles: daily scheduling, counseling, monitoring, and fieldwork. Core systems revolve around five student stats—academics, health, mood, skills, relationships—tracked via profiles. Assign classes (math, arts, etc.) via a grid UI, balancing workloads to avoid burnout; overstudy boosts grades but risks breakdowns.

Counseling sessions are dialogue-driven minigames: select advice from trees, influencing parameters (e.g., “Join club?” raises confidence). Weekends demand proactive interference—menu-select outings like parks or streets, triggering random events (e.g., bust Reika at a karaoke bar). Street patrols add risk-reward: spot-check locations for trouble, but overdo it and affinity drops.

Progression lacks levels but builds via milestones—midterms, cultural festivals—unlocking endings. No combat; “innovation” lies in interdependence: one girl’s crisis affects the class (e.g., low morale spreads). UI is era-typical: icon-based menus, pop-up portraits, calendar overlays—intuitive yet clunky on modern emulators (pixelated fonts, no native saves pre-Windows).

Flaws include RNG-heavy events and opaque stat visibility, demanding trial-error. Yet, innovations like fieldwork presage open-world sim elements, and branching depth rivals Princess Maker. Replayability shines: perfect runs yield boss praise; failures, dismissal. At 20-40 hours per playthrough, it’s addictively granular, as Animetric noted: a “Guardian Sim” devouring “scholarly” hours.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world is a cozy microcosm of late-80s/early-90s Japanese suburbia: Seika High’s cherry-blossom-lined halls, bustling city streets, arcades, and beaches evoke nostalgic shōjo manga vibes. No vast open world—locations cycle via menus—but atmospheric details like seasonal changes (autumn leaves, summer festivals) immerse via stills.

Art direction channels PC-98 anime purity: Hiyoko Kobayashi’s character designs feature expressive, multi-state portraits (e.g., teary eyes for vulnerability) in warm palettes. CG illustrations punctuate key scenes—graduation hugs, exam relief—while “petit” chibi sprites add levity. Static backgrounds (classrooms, urban alleys) are richly detailed, with subtle animations like swaying hair. Windows 95 port retains low-res charm (320×240 scalable), though aliasing shows on HD displays.

Sound design elevates: Iwadare’s soundtrack blends jaunty pop (school themes), melancholic piano (counseling), and upbeat J-pop (successes), spanning vocal tracks from tie-in CDs like Voice Challenger Vol. 2. Voice acting in console ports (absent in PC-98) adds emotional weight—girlish giggles, sighs of relief. SFX are minimal but effective: chalkboard scribbles, door knocks. Together, they craft a bittersweet intimacy, amplifying mentorship’s highs/lows; the graduation theme alone lingers as a tearjerker.

Reception & Legacy

Launch reception was solid in Japan: multi-platform ports (10+ versions) indicate commercial viability, though exact sales elude records. Critics praised its depth; MobyGames logs a single 90% Windows review from Animetric (2001), hailing it “fantastic and addicting” akin to Princess Maker. Players averaged 3.3/5 (5 ratings), critiquing dated UI but loving replayability.

Western impact was muted: Mixx’s 1997 release garnered niche buzz as an “anime sim pioneer,” but Windows 95 compatibility issues and obscurity limited reach. eBay prices ($10-30) reflect collector appeal today, with abandonware sites preserving ISOs.

Legacy endures subtly: it codified “guardian/raising sims,” influencing Princess Maker sequels, Dokodemo Issho, and modern titles like Two Point Campus or Persona social links. As a series cornerstone (preceding Sotsugyō S 1997), it bridged PC doujin to consoles, paving anime sim exports. Cult status grows via emulation, cited in academic gaming histories for gender dynamics and choice architecture.

Conclusion

Graduation for Windows 95 is no flawless masterpiece—its retro UI and RNG can frustrate—but as a historical touchstone, it excels: a richly systemic tribute to teaching’s art, wrapped in anime allure. Exhaustively detailed yet elegantly simple, it rewards patient players with profound narratives of growth and consequence. In video game history, it claims a vital niche as the West’s gateway to Japanese life-sims, influencing a genre now ubiquitous. Verdict: Essential for sim historians and retro enthusiasts—9/10. Fire up an emulator; your students await.