- Release Year: 2016

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Point and select

- Setting: Europe

- Average Score: 85/100

Description

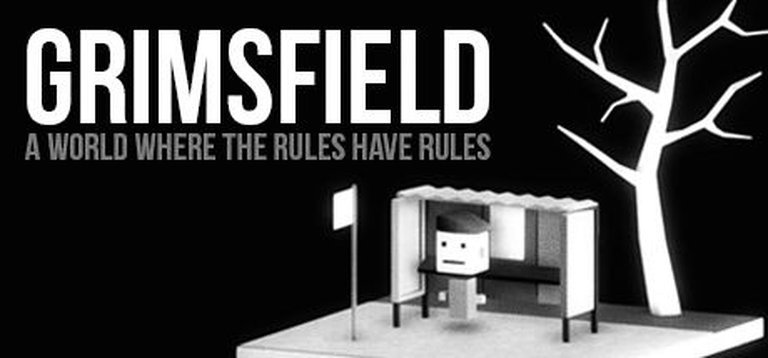

Grimsfield is a short, isometric graphic adventure game set in a mysterious European town. Blending comedy and noir elements, the game follows a point-and-click narrative where players engage in spritzy conversations and explore a densely packed world. Though it can be completed in just over an hour, its surreal setting and understated life lessons encourage multiple playthroughs to unravel its meaning, reminiscent of experimental vignette-style games like Gravity Bone or Dear Esther.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Grimsfield

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (79/100): Grimsfield is not very challenging. And it is also quite short. But it is a clever adventure circling around an artist’s ideals and the reality of everyday life.

brashgames.co.uk : Grimsfield is not a typical game to review, it’s short, snappy and poignant.

steambase.io (91/100): Grimsfield has earned a Player Score of 91 / 100. This score is calculated from 22 total reviews which give it a rating of Positive.

Grimsfield: A Cubist, Kafkaesque Journey Through Northern Absurdity

Introduction

In the vast and often homogeneous landscape of indie games, a title emerges every so often that defies easy categorization, not through bombastic innovation, but through a singular, unwavering artistic vision. Grimsfield, the 2016 debut from animator Adam Wells, is one such title—a short, stark, and brilliantly bizarre point-and-click adventure that serves as a poignant commentary on bureaucracy, artistic ego, and the bleak charm of Northern England. More an interactive vignette than a sprawling epic, its legacy lies not in its runtime but in its potent density, a carefully crafted diorama of cubist despair and dry wit that lingers in the mind long after its brief curtain call. This review posits that Grimsfield is a significant, if oft-overlooked, artifact of indie storytelling—a game that perfectly encapsulates the creative potential of a developer working within their means to deliver a thematically rich and stylistically unique experience.

Development History & Context

Grimsfield was born not in a traditional game studio, but from the mind of a solitary animator yearning to explore a new medium. As Wells detailed in his extensive development blog, his primary background was in 3D animation, creating short films that he felt reached a limited audience. The gaming landscape of the mid-2010s, however, was ripe for experimental, narrative-driven experiences. Titles like Gone Home and Dear Esther were redefining what a game could be, and Wells saw an opportunity to channel his visual style into an interactive format, hoping to create a “theme park dark ride” experience.

The technological constraints were significant. Wells had no formal programming background. His salvation came in the form of Unity and, crucially, the visual scripting tool Playmaker. This plugin allowed him to construct game logic through flowcharts and state machines, translating his animator’s mindset into functional gameplay. This approach was unorthodox; where most developers prototype with primitive art, Wells built the game’s lush, monochrome dioramas first in Cinema 4D, importing them directly into Unity and later layering the interactive systems on top. This “art-first” methodology is central to understanding Grimsfield‘s unique feel.

The development was a four-month solo endeavor, a process Wells describes as “making it up as I went along.” He cobbled together other tools like the Dialogue System asset to manage branching conversations and struggled with the “plumbing” of game design—menus, save systems, and Steam SDK integration—which he found tedious compared to the creative work. This context is vital: Grimsfield is not a product of game design conventions but of an animator’s passionate translation of his aesthetic and thematic obsessions into a new form, with all the resulting quirks and ingenuities.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

You play as a self-aggrandizing, cube-headed poet in the fictional Northern town of Grimsfield, located somewhere off the M62 between Leeds and Manchester. Your goal is deceptively simple: to perform at an open mic night at the local beatnik club. This premise immediately launches you into a Kafkaesque nightmare of red tape and arbitrary rules. To perform, you need a beret, alcohol, and a spoken word license—each item locked behind a new layer of absurd bureaucracy.

The narrative is a sharp satire of systemic oppression and self-absorption. The town is a character itself, a bleak ecosystem where everyone, from the delivery man with a skeleton key to every house to the mayor himself, blindly adheres to a nonsensical social code. The dialogue is peppered with dry, distinctly British humor, evoking the absurdist comedy of Chris Morris’s Blue Jam or Vic and Bob’s Catterick. Characters are hilariously selfish, offering help only to bolster their own egos. You are not fighting a mustache-twirling villain; you are fighting the very concept of “the way things are done.”

Thematically, the game is a potent exploration of the artist’s struggle within a conformist society. The protagonist’s journey is a quest for individual expression in a world that values procedure over passion. The multiple endings (though Wells admits one is “definitive”) and the dense, repeatable hour-long experience invite analysis akin to dissecting a short story. Is the poet a rebel fighting the system, or just another egotist, as the game’s blurb calls him a “knob”? The game smartly leaves this ambiguous, holding a dark mirror to the player’s own desire for recognition.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Grimsfield operates on a classic point-and-click adventure framework, but streamlined to its absolute essentials. The interaction is minimalist: a clear cursor highlights interactable objects and characters, and large arrows guide the player between the game’s isometric diorama scenes. Notably, there is no traditional inventory; items are used automatically when needed, removing the genre’s oft-criticized pixel-hunting and illogical puzzle combinations.

The core gameplay loop is one of conversation and traversal. Progress is made by talking to the cuboid citizens of Grimsfield, navigating their narcissistic dialogue trees to unlock new paths or items. The puzzles are logical and conversational rather than obtuse, ensuring the narrative flow is never broken. This design choice reinforces the game’s focus on story and theme over challenge.

Wells initially prototyped a node-based movement system, akin to Hitman Go, but quickly realized its ergonomic failings. He instead implemented a standard point-and-click controller, a revelation that taught him the importance of user-centric design. The main technical achievement was building a “quest machine” not as a single monolithic script, but as a distributed system of logic across various game objects, a solution he discovered through trial and error. While functional, some flaws are evident; reviewers noted the dialogue could be overly wordy and some potential surprises were scaled back due to technical limitations, such as a planned first-person perspective shift in the finale that was ultimately cut.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Grimsfield is its most unforgettable achievement. The visual direction is a direct carryover from Wells’s earlier animation work, particularly his short film Brave New Old. The world is rendered in a stark, desaturated monochrome palette, evoking the grim reality of a rain-soaked Northern industrial town. Every character, building, and object is constructed from cubes—a cubist aesthetic that is both stylized and strangely oppressive.

This isometric diorama approach makes each location feel like a self-contained vignette, a frozen moment in a larger, sadder story. The art doesn’t just set the scene; it is the scene. The influence of Grim Fandango’s noir atmosphere is palpable, but filtered through a distinctly British, mundane lens. Real-world locations like the Shipley Clock Tower are reimagined into this bleak cube-world, grounding the absurdity in a relatable, if exaggerated, reality.

The sound design is equally crucial. Wells enlisted composer Chris Reed, with whom he had worked previously, to score the game. The brief resulted in a stunning jazz-infused soundtrack that perfectly complements the noir aesthetic. The music is melancholic, smoky, and slightly detached, adding a layer of cool style to the drab surroundings and elevating the entire experience. It’s a masterclass in how audio can define a game’s atmosphere.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Grimsfield garnered a positive, if limited, critical response. It holds an 80% rating on MobyGames based on two reviews. Critics praised its unique atmosphere, intelligent writing, and thematic density, with Brash Games noting it “will stay in your mind for quite some time to come” and 4Players.de applauding its “sparkling entertainment” and “consequent resolution.” The Steam user score is a high 91% Positive from 22 reviews, indicating it resonated deeply with those who found it.

Commercially, it remained a niche title. Priced at $3.99, Wells consciously chose not to release it for free, a decision he wrestled with but felt was justified by the game’s completeness compared to his shorter animations.

Its legacy is that of a cult classic—a beloved hidden gem for a specific audience. Its influence is subtle but discernible. It stands as a benchmark for solo developers, proving how a clear artistic vision and smart use of accessible tools (Unity, Playmaker) can overcome a lack of formal coding skill. It sits comfortably alongside other short-form, narrative-rich experiments like Gravity Bone or Dr. Langeskov, The Tiger, and The Terribly Cursed Emerald, demonstrating the power of video games as a vehicle for personal, stylistic expression rather than just blockbuster entertainment. It showed that a compelling world could be built in a mere hour, challenging prevailing notions of value being tied to playtime.

Conclusion

Grimsfield is a remarkable achievement. It is a game forged in the tension between an animator’s artistic desires and the practical limitations of solo development. Every aspect of its design—from the minimalist, inventory-less interaction to the cubist, monochrome art style—serves its central thematic purpose: to tell a concise, witty, and surprisingly profound story about bureaucracy, ego, and the struggle for creativity in a world of rules.

While its short length and occasionally verbose dialogue may leave some players wanting more, that is perhaps the point. Like a perfect short story or a haunting piece of jazz music, Grimsfield does not overstay its welcome. It arrives, makes its pointed statement with style and confidence, and exits, leaving the player to ponder its meaning. It is a definitive proof-of-concept for the “one-person game” and a brilliant, quirky footnote in the history of indie adventures. For anyone interested in the intersection of animation and game design, or simply in experiencing a truly unique and atmospheric world, Grimsfield is not just a recommendation; it is an essential play.