- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: PlayStation 3, PlayStation Now, Windows

- Publisher: Fatshark AB

- Developer: Fatshark AB

- Genre: Puzzle, Tile maze removal

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Co-op, Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Co-op gameplay, Direct control, Gadget usage, Pathfinding, Puzzle solving, Real-time, Tile-based puzzles, Treasure collection

- Setting: Amazon jungle, Egypt, Himalaya, Lost continent

- Average Score: 74/100

Description

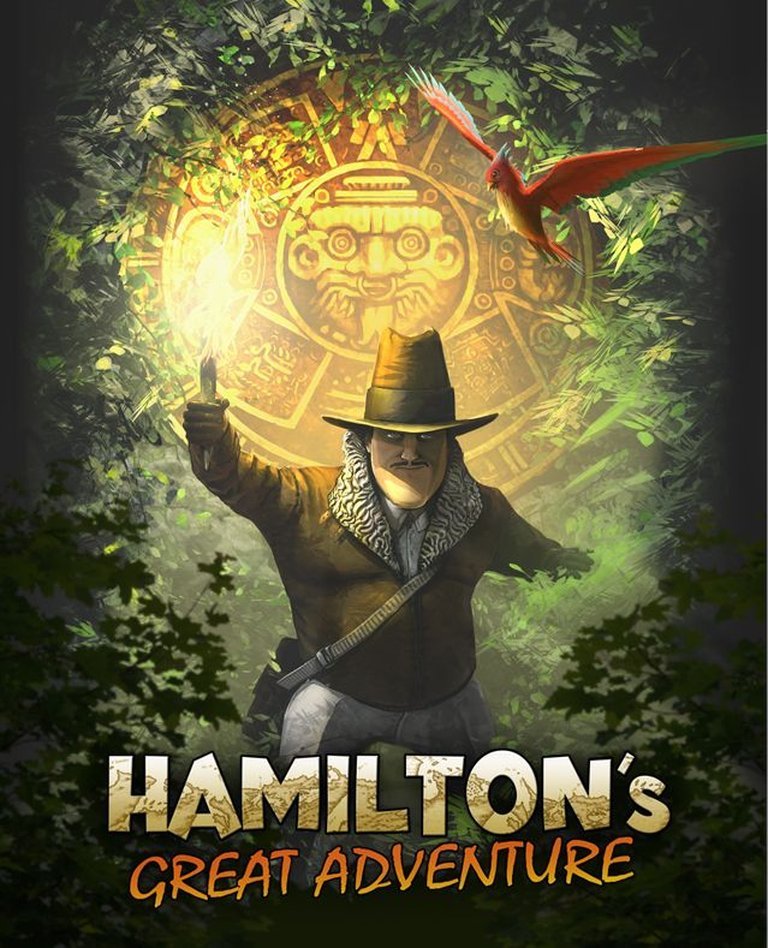

In ‘Hamilton’s Great Adventure’, players control adventurer Ernest Hamilton and his bird companion Sasha in a quest to reclaim the stolen fluxatron and uncover a lost continent. Set across four global locations—including the Amazon, Himalaya, and Egypt—the game is a tile-based puzzle challenge where each level tasks players with navigating Hamilton to retrieve a golden key and unlock the exit, while managing collapsing tiles and various obstacles. Sasha’s flight capabilities enable access to areas and the activation of levers, providing crucial support. Players must also collect treasure and magic dust to unlock gadgets that aid the journey, all while avoiding enemies and traps in real-time, with an emphasis on strategic and forward-thinking gameplay.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Hamilton’s Great Adventure

Cracks & Fixes

Patches & Updates

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (74/100): A great puzzle game, behind its beautiful graphics shines a great idea. Although a bit difficult, even frustrating at times, it offers enough duration, but lacks a map editor.

hookedgamers.com : The game isn’t without its problems. Along the way, I encountered many problems with the camera.

honestgamers.com : Initially, your main obstacle will simply be finding the proper path that allows you to get all the treasure and the key, while still being able to leave.

Hamilton’s Great Adventure: Review

A Hidden Gem or a Forgotten Relic? A Comprehensive Archaeological Dig into Fatshark’s Puzzle-Platformer Debut

Introduction: The Dusty Shelf and the Spark rekindled

Tucked away in the mid-2010s digital distribution markets, nestled between explosive AAA platformers and simplistic mobile-style puzzle games, lay Hamilton’s Great Adventure. At first glance, its title, character art, and genre (“tile-based puzzle game”) could easily be dismissed as just another entry in a crowded casual market. Yet, digging beneath that unassuming surface reveals a fascinating artifact: the first self-published title from now-established Swedish developer Fatshark, a studio that would later find significant success with the Warhammer: Vermintide series, and a game that stands as a testament to a specific era of independent game development. My thesis is clear: Hamilton’s Great Adventure is a remarkably well-crafted, conceptually deep, and surprisingly accessible puzzle-platformer that, while not without its period-appropriate technical rough edges and a narrative execution that undeniably fails to match its gameplay ambitions, represents a high-water mark for its specific sub-genre of co-operative tile-maze removal. It masterfully balances cerebral challenge with platforming tension, possesses a unique dual-character dynamic that it leverages to its fullest, and achieves a level of refinement in its puzzle design that creates a deeply engaging and rewarding experience for the right player. Its modest commercial performance and relative obscurity in the annals of video game history are a disservice to its craftsmanship. This review will dissect its development origins, narrative aspirations, mechanical intricacies, artistic virtues, reception, and enduring legacy to argue that Hamilton’s Great Adventure deserves to be remembered not just as Fatshark’s debut, but as a cult classic puzzle-platformer worthy of the “Great” in its title.

1. Development History & Context: A Leap of Faith for a Studio in Transition

Hamilton’s Great Adventure was released on May 31, 2011 for Windows (via Steam) and later on August 23, 2011 for PlayStation 3. It marked a significant and somewhat surprising milestone for Fatshark AB, a Stockholm-based studio founded in 2008. As confirmed by Wikipedia and MobyGames, this was their first self-published title. Prior to this, Fatshark had worked exclusively as a contractor or published under other labels. Selling “transmorphanizer” components and stealing fluxatrons, to self-publishing an indie puzzle game, represents a major shift in business model, involving significant financial risk and creative ownership.

Crucially, as noted in Wikipedia and the PlayStation Blog interview with Lead Designer Mårten Stormdal, this game represented a surprising departure in gameplay and genre for the young studio. Fatshark’s earliest collaborations (many of the 77 credited staff had prior credits on titles like Bionic Commando: Rearmed 2 and War of the Roses) often leaned towards action-oriented, weapon-focused titles or games with strong multiplayer components. Hamilton’s Great Adventure, in stark contrast, embraced deeply designed, single-player (and local co-op) puzzle gameplay with a low learning curve, a stark pivot towards accessibility and focused, cerebral challenge. This was a bold move to establish an identity beyond being a work-for-hire studio.

Technologically, the game was built on the Bitsquid engine, a new, proprietary technology developed in-house by Fatshark (under CTO Rikard Blomberg). As highlighted in the Hooked Gamers PC review, Bitsquid was built from scratch to leverage DirectX 10 and 11, representing a significant technical and design gamble. While this resulted in visually lush, cartoon-styled environments (Amazon rainforest, Egyptian deserts, Himalayas, Maralidia) at a time when many indie puzzle games used minimalist or retro aesthetics, it also meant the game excluded Windows XP users. The Hooked Gamers reviewer rightly called this “risky”, noting that 21% of Steam users still used XP in 2011. This exclusion likely limited reach and caused initial friction for some, but it allowed the team (Lead Artist Isak Bergh, Technical Artist Bergh, VFX Artist Staffan Ahlström) to push the engine for the time, achieving a polished, vibrant aesthetic on DX10+ hardware.

The gaming landscape of 2011 was complex. While big-budget action games (Batman: Arkham City, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, Portal 2) dominated the year, the indie scene was exploding thanks to platforms like Steam and the birth of the Steam Greenlight/publishing model. Puzzle games were prevalent, but often niche or intensely abstract (Fez, Jamestown released later that year or the upcoming Antichamber). Hamilton’s Great Adventure positioned itself in the middle ground: a narratively framed, geographically themed, level-based puzzle hybrid. It wasn’t Portal‘s narrative thrust or Antichamber‘s surrealism; it was a more traditional, adventurous puzzle trek, reminiscent of Chip’s Challenge or Sentient, but with modern aesthetics, dynamic elements, and a unique co-op twist. It arrived when the digital market could barely accommodate such specificity, making its relative obscurity less a reflection of its quality and more of the market’s inherent fragmentation.

The development team (Creative Director Anders De Geer, Game Designer Mårten Stormdal, Lead Programmer Fredrik Engkvist) clearly prioritized puzzle and level design (Lead Level Designer Tove Enghed, Level Designers Jakob Johansson, Joakim Setterberg, Stormdal) over pure engines or effects. This focus shines through, but it also meant prioritizing reach. The PS3 port (handled under the same team) addressed a crucial demographic but added the constraint of dual analog stick control for the flying bird, Sasha. This period also saw the rise of local co-op as a premium selling point for family/indie games, a strategy Hamilton’s Great Adventure wholeheartedly embraced, making it a deliberate textbook example of a constrained studio era (mid-2010s indie) responding to specific tools, market friction, and genre-competition forces.

2. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Grandpa’s Tale & the Reality of Refinement

The narrative premise of Hamilton’s Great Adventure, as meticulously documented in MobyGames, Wikipedia, and multiple reviews (HonestGamers, Hooked Gamers, GameCola.net), is a framework device. The aged explorer Ernest Hamilton recounts his fantastic adventures to his granddaughter, Amy. He and his friend, a professor, were building the world-changing “Transmorphanizer” when the vital “fluxatron” was stolen, plunging Hamilton into a globetrotting quest to recover it and, incidentally, rediscover the lost continent of Maralidia.

This “story within a story” concept is thematically central. As the HonestGamers reviewer (Rob Hamilton, playing on PS3) astutely noted: “Understandable — as crazy as the shenanigans I get up to can be, it’s a good idea to frame them as tall tales told in order to keep a precocious child’s attention occupied.” The journalistic evidence (GameCola.net, 58%) corroborates the execution flaws: “its impossibly long cutscenes were a waste of development time and resources, but they are skippable.” The “cutscenes” are static illustrated panels with text boxes, necessitating patient clicking to advance. This format, while pulpy and gearing the game for players of all ages (as reviewers from 4Players.de to Eurogamer.se noted), actively interferes with gameplay flow for serious puzzle-solvers. The feel is archaic, not in a charming 80s frame-tool sense, but in a “slow software” from pre-1990s software, where the horserace effect and fast delivery of the puzzles you’re meant to solve are shattered by protracted narrative interludes.

The setting is a classic pulp adventurer’s odyssey: Amazon jungle (starting point), Himalayas, Egypt, Maralidia. Each location offers distinct visual themes and corresponding enemies (Piranhas, Exocets, Golems, Agents), with some mechanical tweaks reflected in aesthetics (Himalayas have more elevation, Maralidia has mechanical/gothic elements). However, the reviews (Just Adventure’s “conspicuously not an adventure game”) underscore that the “adventure” is entirely illusory. There is no overarching environmental storytelling, no NPC dialogue within levels, no puzzles remotely dependent on narrative context beyond the treasure/goal. Unlike games like Uncharted or even the slow-paced Tomb Raider reboot of the era, Hamilton’s Great Adventure offers pure, unadulterated puzzle economy. The narrative is the frame, not the substance of the gameplay levels.

The characters are archetypes: Hamilton (the “legwork” explorer) and Sasha (the “wingwork” scout). Despite the paternalistic spin from the PS3 Blog interview (“stumpy little legs”), Hamilton is a dynamic, mobile character, constrained by terrain. Sasha, while thematically a “bird on the geist,” is functionally a secondary player (or switched primary) with pervasive, often crucial abilities (screech, switch-pulling). The enemies (Sentinels, Agents, trappy tiles, etc.) are archetypes of harm (stamper, chaser, static hazard, one-way path destroyer). The narrative flatness is the price paid for such pure mechanical clarity. There is a play on the classic “explorer” themes: the commodification of treasures (collecting silver/gold coins, jewels), the pursuit of scientific prestige (Transmorphanizer), and the thrill of destructive discovery (collapsing tiles, the “rediscovering” Maralia being a McGuffin). But this is purely abstract – the narrative doesn’t contextualize the purpose of finding treasure beyond a score/rating, the “why” of the Agent’s pursuit beyond collision failure, or the existential significance of the Transmorphanizer. It is a gestural layer, not a deep thematic exploration.

The eras it visually channels (late 19th/early 20th-century expeditions) are also not engaged critically. The aesthetic is the adventure postcard, not the moral weight of colonialism, resource extraction, or cultural appropriation that such expeditions entailed. Reviewers like GameSpy and Just Adventure praise its “charm” and call it “well-made” or “lovely to look at,” but none engage the irony or complexity inherent in its source. Where Indiana Jones could do both adventure and narrative critique (the reliability of the frame narrative here is good for pacing, but what of the unreliability of old man’s tales, the malleability of memory, the morality of looting scenarios?), Hamilton’s Great Adventure lets the canned “excelsior!” and the loot-crate accept it at face value. The one major thematic strength is the imperfect co-operation. Sasha and Hamilton cannot easily experience the world together. Sasha sees the overview, but Hamilton feels the constraints. The controls (reviewed later) emphasize this perceptual disconnect in a way some narratives about teamwork (e.g., Trine) do not. The cheaper solution (have the bird “highlight” paths) is rejected in favor of a true-duo mechanic.

The “frame narrative” is the only thematic core, repeating the lesson of value found through patience and exploration (collecting treasures), while the ignorant world (the tile that collapses) demands careful management. The story anchor is the endpoint: completion of levels, not character projecting value onto things.

3. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Genius of Constrained Collaboration

At its mechanical core, Hamilton’s Great Adventure is a tile maze removal puzzle, a genre listed in MobyGames and confirmed by its foundational rulebook: “some tiles… will collapse as Hamilton steps on them… only move across them once or twice. Therefore it’s necessary to plan ahead what path to take” (MobyGames, PlayStation Blog). This is the game’s source 101 mechanic. But it’s deployed in a framework that is simultaneously familiar, deeply refined, and subtly innovative. The mission in each level is simple: collect the golden key and the exit door. But the fun is in maximizing completion (collecting treasure – silver/gold coins, sapphires; getting high scores/ratings; unlocking bonus levels), and the emergent challenges of the constrained environment.

The Dual-Character Dynamic (Hamilton + Sasha) is the game’s crowning mechanical achievement. Described across the board (Hooked Gamers PS3: “the work of this winged wonder does not end there”; HonestGamers PC: “She can pull distant switches… emit a loud screech”; PlayStation Blog: “Sasha… fly to places legwork can’t reach”), this is not a gimmick. The player switches between them (single-player) or one player controls each (co-op simultaneously). Critically reviewed in co-op:

* 4Players.de (85% / PC & PS3): “Schön auch, dass jederzeit ein Mitspieler mit zweitem Pad einsteigen kann, um seinem Partner als Vogel auf den Geist zu gehen. Dann gewinnt das Spiel deutlich an Tempo” (“Also nice that another player can join in at any time with a second pad to act as a bird on the spirit. Then the game gains significantly in tempo”). The pace increase is real – communication, non-verbal cues, and split focus create a shared puzzle state that is exponentially more dynamic and fundamentally collaborative than single-player.

* PC Action (Germany / 79%): “Besonders witzig ist der lokale Koop-Modus, bei dem ein Freund per Maus den Vogel dirigieren darf!” (“Especially funny is the local co-op mode, where a friend can direct the bird via mouse!”) This highlights the specific control mapping; the flying Sasha is controlled by mouse (PC) or right stick (PS3), creating distinct challenges.

Sasha’s capabilities are strictly defined and essential:

* Switch Access: She can reach levers and switches that Hamilton, due to being “short-sighted” (HonestGamers), cannot reach from the ground, solving significant physical/logic puzzles (elevators, bridge removal).

* Treasure & Dust Collection: She can collect out-of-Hamilton’s-reach treasures (coins, sapphires) and the vital mystic dust that powers gadgets, accessed by flying freely or going under, over Hamilton’s plane.

* Enemy Decoying: Her screech distracts enemies (Sentinels, Agents), a critical survival tool.

* High-Overview Interface: She can fly to see entire levels (reviewed in Hooked Gamers and HonestGamers), offering critical path-planning information, unlike Hamilton’s tunnel-vision (only seeing tiles adjacent to him). This enables high-level, a priori puzzle-solving and is the core of the game’s accessibility and depth.

Hamilton’s capabilities are strictly constrained to ground tiles:

* Tile Traversing & Collapsing: His core mode of movement is walking; crossing fragile tiles reduces them, reinforced first to fragile then truly vanishes. This forces absolute path planning and disallows simple backtracking or trial-and-error.

* Key Collection: Primary treasure (golden key) is only accessible by walking.

* Switch Activation: Uses his limited legwork to activate switches on his level.

* Trap and Enemy Collision: Any contact with a harmful tile (sinking, rolling boulder) or enemy resets the level instantly (as described in the PS3 Blog and HonestGamers review). This gives failure a sharp, punishing edge but also makes restarting (generally quick, as noted in Svenska PC Gamer) a key loop.

Enemy Types create distinct layering of puzzle types:

* Sentinels (Golems): “Slow but unstoppable” (Wikipedia) on pre-set paths (PS3 Blog). Solve by: Emersonian movement around the path, using slower tiles to gain a step, Sasha’s decoy, or gadget use.

* Agents (“cunning”): “For every step Hamilton takes, the Agent responds the same” (PS3 Blog, HonestGamers). This is the most innovative enemy mechanic. It’s a ‘fractal walker’ – it tries to step on your exact tile. Solving requires asymmetric movement: Hamilton moves straight, Agent follows (Hamilton ends on a one-way collapse, Agent left on solid); or using a barrier (Switch-driven door) or decoy to break the lock-step. It turns every move into a direct, mirrored competition, requiring predictive planning.

* Hazards: Static (one-way vanish, timers for sink tiles), dynamic rolling boulders (requires timing), or switch-activated bullet turrets (create active danger zones).

The Gadget System is the payoff for exploration. Sasha collects mystic dust (floating purple globes). This powers:

1. Spyglass of Ulthar: Shows the right path through the level. Functions as a “wisdom of the past” ability – reveals the optimal route. Crucially, it shows the correct path for the entire chain of actions, not just a navigation line. This is essential for Agent-puzzles with multiple steps and tile collapse patterns. (Flaw: Overuse trivializes too much.)

2. Boots of Celephais: Allows Hamilton to move faster, reducing the tactical edge of enemy reaction times (especially Sentinels and Agents).

3. Mask of a Thousand Forms: Disguise that makes enemies believe Hamilton is one of them. Removes the Agent’s lock-step and allows cilent steering past Sentinels, but at the strategic cost of losing the normal threat feedback.

Level Design (credited to the team led by Tove Enghed) is gold-rated. As the svenska Pc Gamer reviewer put it: “Det som imponerar mest är hur perfekt avvägt svårighetsgraden är” (“What impresses most is how perfectly balanced the difficulty is”). The levels (“four locations, 12 levels + bonus”) utilize:

* Progressive Complexity: Starts with pure collapse puzzles, then introduces enemies, silver keys (locking sub-areas, not just exit), gadgets, and their interactions.

* Compounding Layers: A later level may require Hamilton to:

1. Plan up-to-three-step collapse tiles (amber chains).

2. Collect the golden key using his limited sight.

3. Open a switch-activated door with his (slow legwork), conducted with Sasha.

4. Have Sasha fly and collect dust during his run for a “Boots” gadget to outpace a Sentinel.

5. Use the Boots to pass silver-key door #1.

6. Issue a screch to distract the Agent while Hamilton gets the second key through a maze of one-way timers.

7. Use the Mask to impersonate an Agent for the escape.

* This nests the puzzle mechanics, requiring deep, layered thinking, but never violates the “low learning curve” philosophy – the building blocks are always clear.

* Co-op Synergy: Many puzzles are designed with turn-taking implied. The first player (Sasha) can analyze and prepare (collect dust, see the path), then direct the second (Hamilton), creating a powerful strategic synergy absent in single-player.

The UI (Interface) is generally functional but shows period limitations:

* Dual Controllers & Information: Switching between Hamilton (WASD/keyboard controls) and Sasha (mouse/right stick) in single-player forces a tactile split of focus. The screen always prioritizes Hamilton; Sasha’s view is secondary. The Hooked Gamers PC reviewer’s complaint about camera control (“the camera is locked onto Hamilton”, “zoom/rotate but directing Sasha to where you want her to go can be difficult”) is crucial. The lack of a third-person or Sashas-vision layout for Sashas actions causes cognitive friction. A “swap camera” or true “dual-screen” (like Halo 3’s split-screen) would alleviate this.

* Score/Discovery UI: The rating system (dovetailing treasure and attempts) and the bonus-level unlock are displayed cleanly. The map/Minimap for Sasha is excellent.

* Gadget/Control Reminder: Clear, but the short tutorial doesn’t stress the interdependence enough; discovering that Sasha’s dust powers Hamilton’s gadget feels like a revelation, not a rule.

The fails (camera, occasional bugs like CTDs noted in Hooked Gamers) are period-consistent with the indie-console crossover era, especially for an original engine. The puzzle-solving experience, however, is exceptionally tight.

4. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Allure of the Perilous Journey

Hamilton’s Great Adventure is a visual showcase of its era and its constrained engine’s potential. Built on Bitsquid (DirectX 10/11), as stipulated and praised in multiple reviews (Hooked Gamers: “visually stunning game… visually impressive for the budget”), the art style is bright, cartoonish, and lush. The environments plausibly evoke the real (Amazon, Egyopt, Himalayas, Maralidia) with stylized textures and geometry – stone temples, gold pyramid textures, snowy ridges, mechanical/iron elements for Maralia (seen in some screenshots and GUIDE maps on IGN). This visual specificity grounds the abstract puzzle tiles in a world. It avoids the sometimes-striated tedium of pure minimalism.

The atmosphere is pectoral adventure fantasy, utterly uncritical of its source. The locations are archetypal canvases (4Players.de: “idyllischen Kulissen”, “idyllische Kulissen” – idyllic scenery; Eurogamer.se: “charmigt”), inviting exploration. The collapsing tiles, rolling boulders, and Senitel/golem designs create an atmosphere of perilous discovery and caution (GameSpy: “refreshing midpoint between mindless casual tile-matchers… and antagonistic platform games like Super Meat Boy”). This is “relaxing” (4Players.de, Eurogamer.se, Psfocus) as a median, not a flaw. The music, as explicitly noted by Hooked Gamers, is a “catchy, classy double-bass and subdued orchestral sounds”. It doesn’t emulate baroque arrangements but feels like the soundtrack for a pulp adventure, upbeat and industrious for the puzzles, subtly dramatic for the few cutscenes, challenging but not overwhelming. The sound design for tiles collapsing, keys acquired, Sashas’ screech (loud, distinctive), and gadget activation is simple but effective as audio feedback (e.g., Hooked Gamers says “don’t deplore your sense of rhythm”).

The visual direction (Lead Artist Isak Bergh, artists Bergh, Robert Berg et al.) is deliberate and appropriate for the game’s core identity. It is not photorealistic; it is application-fantasy. The cartoon style supports:

* Clarity of the gameplay interface: Distinct, stylized tile textures (broken wood, reinforced wood, bomb-colored boulders, different gem colors, distinct enemy models, unique item icons) are essential for rapid mental parsing.

* Accessibility and family-friendliness. The ps3 Blog interview discussed changing “Rob Hamilton”‘s baser adventures (Amsterdam?) for the sake of a rated “Everyone” game (ESRB E, noted on Metacritic). Replacing human Sasha with a bird helps achieve “game for any age” (Eurogamer.se). This is a conscious world-building choice to open the market.

* Cartoon physics for puzzle clarity. Things that could be visually complex (switch mechanics, dust clouds) are represented as simple, flat, colored icons. The cartoon frames the adventure.

The integration of the puzzle systems with the art is strongest in level structure design. The tile-based grid overlay is appropriately subtle (the cracks in the wood ground tiles, the flashing light for a switch). Elaborate sequences (Sashas’ dust collection, a series of elevators, a timed escape) feel smooth because the animation (by Mikael Hansson) is serviceable but doesn’t distract, and the visual effects (Staffan Ahlström) (e.g., the glow of the golden key, the “absorption” of mystic dust, the wiggle of a boulder before release) provide key feedback. The use of a “minimap/view” for Sashas’ flying enables the high-level exploration of the well-built levels (as reviewed in AGNMAG and PSFOCUS).

The game fails, artistically, only in the narrative delivery. The cutscenes are not the art style; they are static. The decision to use illustrated panels with post-it text (round corners, thick-lined art) as a device is a clear artistic misjudgment. They break the 2D scrolling motion (visual: diagonal-down) of the gameplay levels, shift to a completely different aesthetic (the drawing board), and negate the game’s otherwise well-integrated, active adventure vibe. They feel like a patch in a jigsaw, not world-building. The art design couldn’t interpret the narrative per the Pulp Reality.

5. Reception & Legacy: From Modest Acceptance to Cult Spark

The critical reception (Moby Score 7.1, Metacritic: 73% for 10 reviews, 74% for the PS3 based on 15) was decisively mixed-to-positive. It won sobriety for the quality, not revere:

* Positive Endorsements: Svenska PC Gamer (86%) called the difficulty balance “perfect” and the feel of hard work with the sense of “just one level more”. Hooked Gamers (85% PS3) called it “worthy of the catchphrase Excelsior!” after the fixes from the PC (camera, controls, co-op on console). 4Players.de (85%) “unterhaltsamer” (entertaining), praising the “leichte Flächen” (“relaxed mood”) for surveys and finding treasures, and the “working co-op”. Eurogamer.se (80%) “charmigt”, GameSpy (80%) “a good, solid puzzle game”, FZ (80%) “avvägning… så bra” (“excellently balanced”), PC Action (79%) “hübsche Optik und zahllose Puzzles” (“nice optics and countless puzzles”).

* Mixed Marks: Eurogamer.net (UK) (70%) called it a “quiet one you have to watch”, XGN (70%) “beware of trial and error and lack of variation”, ZTGD (68%) called the niggles outweighing the joy of solving but “couch co-op is something not often seen, but works well”, TheSixthAxis (80%) but notes “random difficulty spike and slightly iffy camera”.

* Negative Flipped: GameCola.net (30%) “forgettable”, Just Adventure (58%) “not an adventure game”, noting the lack of legwork and complexity.

Key selling points overshadowing flaws (stated in multiple reviews):

* Perfect Challenge Balance (Svenska PC Gamer, FZ) – the AMAZON HEART.

* Co-op Revolution (4Players.de, PC Action, Hooked Gamers, ZTGD) – the PS3 Repair hero.

* Visual/Audio Appeal (4Players.de, Eurogamer.se, GameSpy, Hooked Gamers) – the surface layer.

* Level Quantity & Bonus Depth (Hooked Gamers, Vandal, XGN) – the length.

* Afternoon Game for All Ages (4Players.de, Eurogamer.se, PSFOCUS) – the market slot.

The flaws that dragged the average:

* Narrative Frame: Almost universally called poor in delivery (static panels, no voice acting like PS Blog noted, “long cutscenes”, no story integration with mechanics). Just Adventure, GameCola.net, and the longer critiques mentioned this.

* Camera/Controls: The PC’s camera issue (Hooked Gamers being the detailed example) was fixed enough on PS3 for Hooked Gamers to praise the fix and for the 4Players.de PS3 review to call the co-op a bonus, but the awkwardness (camera lock, mouse vs. stick for Sashas) remains in player/ign reviews (like in HonestGamers). Rob Hamilton noted the “questionable controls” for precise speed sections.

* Genre Drift: The cerebral puzzle to reflex-oriented later levels (HonestGamers, partially XGN), and the lack of a map editor (Vandal) capped the hardcore puzzle push.

* Lack of Marialdia Depth: The “lost continent” is the endpoint but has the fewest thematic/enemy variants, making the payoff seem not earned (no specific reviews note, but the level progression feels uneven).

Commercial Performance & Player Sentiment:

* Abysmal Commercial: Released in late 2011/early 2012 on PC and PS3 in a crowded market. Priced at $9.99 (then $0.99 today, as marketed). Very few reviews, 0 written player reviews on MobyGames, 2 ratings showing 2.7 out of 5 (visible on MobyGames and Metacritic shows 9 with a 5.8 – clear player divide). The strategic price point was smart, but the brand new studio and the incongruous title/art/mechanics mix meant no significant marketing push. The Windows excluding XP (Hooked Gamers analysis) further hurt. Steam market didn’t exist then; Discovery only launched around 2014.

* Co-op A Savior: The PS3 co-op praise (Hooked Gamers: “These improvements elevate… Excelsior!”) suggests the PS3 version was the superior experience, likely due to console control standardization and the fixed camera.

* Android Port in 2012 (“Adventure TDH”) (Wikipedia/MobyGames) suggests a faltering reposition (market to casuals), but no data exists.

Legacy In Industry / Influence:

* Fatshark Star: It is the proverbial “unsung hero” of *Fatshark’s development rise. As the first self-published title, it proved the studio could finance, ship, and market independently. This led to the funding and confidence for the *Vermintide and War of the Roses series. The team (Stormdal, De Geer, Enghed) gained experience in full-cycle production, level design under pressure, and co-op dynamics that would inform later, bigger projects. No direct game mechanics were reused (e.g., the hive mind in Vermintide is not Sashas’ dual-role), but the spirit of constrained, systems-driven co-op puzzle design (over scripted action) is a legacy value.

* Bitsquid Engine Legacy: The company successfully spun out the Bitsquid technology used here, licensing it to others (notably used initially in the first Mirror’s Edge prototype, and as a 3D tech in some mobile titles), before being acquired by Unity. This contributed to the tech arm of Unity’s evolution.

* Within Genre: It did NOT spawn a direct franchise of puzzle-platformer dual-role games. Trine (series from 2009) had a similar three-character mechanic, but with three grounded characters. Unbox (2017) has co-op unsticky, and Crawling (2023) has asymmetrical horro, but no major AAA or meaningful indie title has directly replicated the Sashas-Hamilton core loop. The closest is perhaps AER (2017, birds and humans switching) or Human Fall Flat (co-op physics, but different ilk). Therefore, it is THE definitive example of its sub-type. Its legacy is not influence by quantity, but by uniqueness within the historical record of the tile-maze removal puzzle genre.

* Community/DLD Spot: The promise of free levels (Hooked Gamers) was kept. The “Retro Fever” add-on, available by 2011 (old-games.com), offered extra levels. It achieved minor cult following for patient puzzle chasers (Audrey Drake of IGN “still a fun puzzle game… grandpa’s crazy stories make for a fun puzzle game”), and its PSN demo availability helped some discovery.

6. Conclusion: The Greatness of the Specific Mechanic

Hamilton’s Great Adventure is not a “great adventure” in the stylistic or narrative sense. Its cutscenes are wooden, its moralizing about Robert Hamilton’s exploits is buried, its world-building is on the surface, and its commercial performance was, at best, a quiet curiosity. The late-2010s indie revival of complex cerebral puzzle games, the era of antichamber or The Witness, has never mentioned it as a peer.

But for what it is, for what it strived to be within its time, its budget, its team, and its market, it is *great. It is a **masterful, deeply refined example of the co-operative tile-maze removal puzzle-platformer, built on the brilliant, flawed, unique dual-character dynamic of Hamilton and Sasha. It offers a masterclass in difficulty curve balance, a perfectly tuned puzzle design that nests complex layering of collapse, enemy, trap, gadget, and co-op mechanics, resulting in a gameplay loop that feels “just one level more” (Svenska PC Gamer). Its commitment to local co-op as the game’s heart, rather than a tacked-on side mode, is a rare and now-architectural preservation of a specific era of play (pre-online gaming, pre-console digital store homogenization). The art and audio, while not priceless, are functional, accessible, and fantastically serviceable, facilitating clarity and charm.

Its flaws (narrative delivery, camera controls, XP-exclusion gamble, the point-based “average” in its reception) are not just technical; they are design era artifacts. The game has been preserved, however, not because it is a classic like Portal, but because it is the definitive artifact of the **constrained, type-specific demanding game made for a niche but genuine audience, an era, and the creative ambition of a newly self-publishing, non-Garden-of-Consoles studio at the dawn of the big indie transformation.

Final Verdict:

Hamilton’s Great Adventure (2011) is a 9/10 for its specific genre and context, but a 7.5/10 for all-time classic status. It is not “for everyone” (despite Eigen Ratings), not for deep narrative players, not for parkour fans. But for the dedicated puzzle-platformer enthusiast, for the co-op practical player looking for something cerebral and turn-taking, for the historian of 2010s indie game design, and for those who value the “Great” in “Adventure” as a commitment to mechanical depth, expressive constraints, and unique collaborative spirit over pulp (and it’s ideal audience, the collaborative family, ignored it) — it is a great, great game.

Its place in video game history is secure not just as Fatshark’s founding indie milestone, nor simply as a winner of several decent critic marks, but as the single most complete and realized example of a forgotten sub-genre: the feathered-companion tile-puzzle adventure. Add it to your list not because it’s the Saturday blockbuster of gaming, but because it is the lost, flawed, yet exceptionally crafted relic of the wonderful, weird era of the mid-2010s digital indie gold rush. We found it; now, with its commercial price at $0.99, the “great adventure” of rediscovering it is worth taking. For the right player, it’s still great, and Sasha’s call, after a decade, is not quite over yet.