- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: eGames, Inc.

- Genre: Compilation

Description

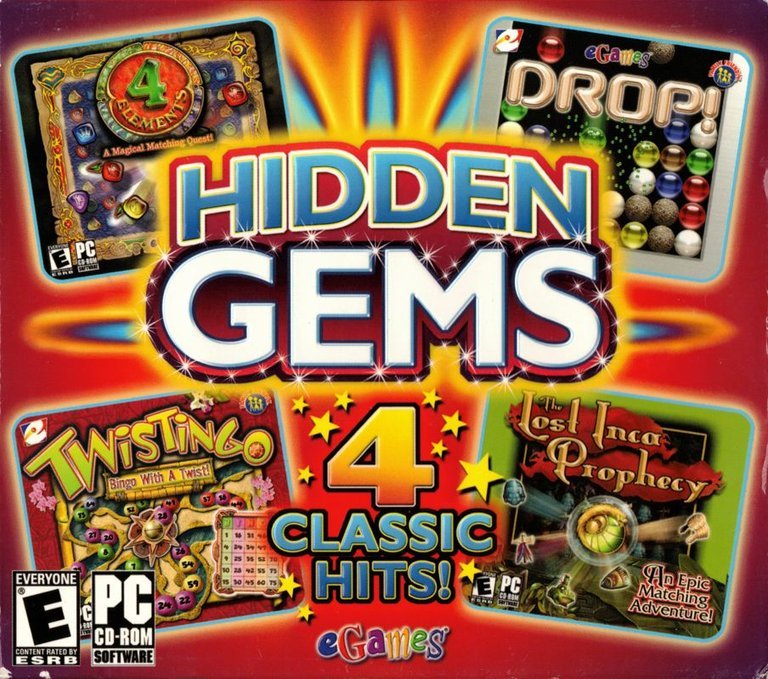

Hidden Gems is a 2010 Windows compilation game published by eGames, Inc., bundling together four distinct casual titles: 4 Elements (2008), Drop! (2002), Twistingo (2005), and The Lost Inca Prophecy (2009). Rated for Everyone, this collection offers a diverse mix of gameplay styles without a unified narrative or setting, simply presenting assorted indie-style games from the early-to-mid 2000s.

Hidden Gems Free Download

PC

Hidden Gems: A Comprehensive Review of a Casual Gaming Compilation

Introduction: Unearthing a Digital Time Capsule

In the vast ecosystem of video game history, the term “hidden gem” carries a specific weight—it implies a title of merit that slipped through the cracks of mainstream consciousness, often due to niche appeal, limited marketing, or being ahead of its time. The 2010 Windows compilation Hidden Gems, published by eGames, Inc., presents a fascinating case study in this very concept, but with a twist: it is not a single hidden gem but a curated collection of four distinct titles, each a minor obscurity in its own right. This review argues that Hidden Gems (Moby ID: 225695) is historically significant not for the revolutionary quality of its contents, but as a deliberate artifact of a transitional era in gaming—a physical, retail-bound time capsule attempting to preserve and monetize the burgeoning “casual” and “downloadable” game space of the early-to-mid 2000s for a late-2000s audience. It represents a publishing strategy aimed at the low-end PC market and casual gamers, bundling titles that were originally digital or small-budget releases into a single, accessible package. Its legacy is that of a quiet footnote, embodying the industry’s efforts to repackage and redistribute the era’s overlooked puzzle and adventure games before the complete dominance of digital storefronts like Steam.

Development History & Context: The eGames Blueprint and the Casual Wave

The Publisher and the Era: Hidden Gems was released in 2010 by eGames, Inc., a publisher with a established business model centered on budget compilations and “value” titles, often targeting big-box retailers and the “casual” PC gaming demographic. Their output frequently consisted of collections of smaller games, arcade ports, or re-releases of older titles. This places Hidden Gems squarely within a specific commercial context: the late 2000s saw a massive expansion of the “casual games” market, fueled by the success of websites like Big Fish Games and the rise of mobile gaming (the App Store launched in 2008). However, in 2010, the PC retail market for these games still existed alongside the rapidly growing digital distribution.

The Source Material & Technological Constraints: The compilation aggregates four games from a five-year span (2002–2009), each originally developed as a standalone, likely small-team or even solo-dev project, with modest budgets and technological aspirations:

* Drop! (2002): A product of the early 2000s casual web game boom (Newgrounds, Shockwave), built for browser plugins or basic executable distribution.

* Twistingo (2005): Likely a Java or basic Windows puzzle game, reflecting the era’s experimentation with simple, addictive mechanics.

* 4 Elements (2008) & The Lost Inca Prophecy (2009): These are slightly newer and likely showcase the modest graphical and design improvements of the late 2000s casual space, possibly utilizing Adobe Flash or early Unity.

The technological constraints are implicit: these are not 3D-behemoths. They are 2D, likely sprite-based or simple vector games, designed for low system requirements—perfect for the “low-end” gaming rigs mentioned in the Reddit source. The compilation itself required minimal engineering—simply gathering executables, perhaps wrapping them in a simple launcher, and creating basic packaging and retail discs. There was no narrative or mechanical cohesion between the games; the value proposition was purely quantitative: “four games in one.”

Gaming Landscape at Release (2010): By 2010, the industry was at a crossroads. The “hardcore” market was deep into the Xbox 360/PS3 generation with complex, cinematic RPGs (e.g., Mass Effect 2, Dragon Age: Origins). Simultaneously, the “casual” market was exploding on phones (Angry Birds launched in 2009) and Facebook (FarmVille). The mid-tier “downloadable casual PC game” market was being squeezed. Hidden Gems thus feels like a last-gasp effort to sell a bundle of older, digitally-native casual games to an audience still buying physical discs at Walmart or Best Buy, perhaps as a gift or for a family PC. It competed not with Skyrim, but with other “1000 Games!” type compilations and the nascent digital storefronts that would soon make such physical bundles obsolete.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Whispers of Stories in Puzzle Shells

The narrative content across the Hidden Gems compilation is, by necessity of their genres and budgets, minimal and archetypal. However, analyzing these thin stories reveals the common thematic through-lines of early 2000s casual game design: simple mystery, light adventure, and abstract problem-solving.

- Drop! (2002): Based on its title and era, this is almost certainly a “falling block” or “match-3” puzzle game (like Bejeweled or Dr. Mario). Any narrative would be purely decorative—a framing device like “clear the screen of gems” or “pop bubbles to save the kingdom.” The theme is pure, unadulterated gameplay loop: pattern recognition and quick reflexes. There is no character, no dialogue, no plot.

- Twistingo (2005): The name suggests a bingo-like or number-matching mechanic (“twist” + “bingo”). Narrative, if present, would be similarly vestigial—perhaps a carnival or lottery theme. The core experience is chance and pattern-spotting, evoking the universal theme of “games of luck.”

- 4 Elements (2008): This title points directly to an elemental puzzle or match-3 game (likely matching earth, air, fire, water symbols). The theme here is alchemical or natural balancing. The narrative wrapper, common in such games, would be a quest to “restore the four elements” or “cleanse a corrupted world,” providing a very loose, fantasy-tinged justification for the puzzle mechanics. It taps into a primal, mythological understanding of the world’s composition.

- The Lost Inca Prophecy (2009): This is the compilation’s most narratively ambitious title. The phrase “Lost Inca Prophecy” immediately evokes archaeological mystery, ancient civilizations, and impending doom. It suggests an adventure or hidden object game where the player explores Incan (or Incan-inspired) ruins, deciphers clues, and prevents a cataclysm. The themes are exploration, cultural discovery (albeit heavily stereotyped), and puzzle-solving as a key to salvation. Compared to the other three, it likely has a more structured, quest-like progression with locations and a semblance of plot, albeit delivered through static text or simple cutscenes.

Synthesis of Themes: Across the compilation, the dominant theme is cognitive engagement through pattern and logic. The narratives, where they exist, serve as thin justifications for puzzle-solving. They represent a pre-“narrative indie” era for casual games, where story was an afterthought, not the primary draw. The “hidden gem” in a thematic sense is that each game, in its own simple way, asks the player to engage with a structured system and find order in chaos—whether that’s aligning gems, matching numbers, or decoding a prophecy.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Four Pillars of Casual Puzzles

The core value of Hidden Gems lies in the variety of its four constituent gameplay loops, each representing a popular casual genre of its respective release year.

- Drop! (2002): Core Loop: Classic falling-block puzzle. A player controls a falling object (a gem, a block) and must rotate/position it to create matches (likely of 3 or more) with existing objects on a grid. Matches clear, new objects appear, and the playfield fills. Mechanics: Speed increases with levels. Scoring for chain reactions. Likely includes a “next piece” preview. Innovation/Flaws: As an early-2000s title, it likely lacks modern quality-of-life features like hold pieces or sophisticated tutorials. Its innovation was in being a competent, early entry in a now-saturated genre. Its flaw is probable simplicity and lack of depth compared to later titans like Tetris Attack or Puyo Puyo.

- Twistingo (2005): Core Loop: Bingo or number-matching variant. The player has a card with numbers or symbols; numbers are called randomly, and the player must mark them. The goal is to complete a specific pattern (line, X, blackout). Mechanics: Power-ups might be available (e.g., “free space,” “extra call”). Progressive difficulty via faster calls or complex patterns. Innovation/Flaws: The “twist” in the title suggests a unique rule or modifier (e.g., numbers can be “twisted” to other values). Its innovation is in tweaking a classic, universally understood game. Its flaw is potential reliance on randomness over skill, and limited strategic depth.

- 4 Elements (2008): Core Loop: Match-3 puzzle with an elemental twist. Swapping adjacent gems to create matches of 3+ of the same element (Fire, Water, Earth, Air). Mechanics: Matches of 4 or 5 likely create special gems (bombs, row/column clearers). The game probably has a level-based objective: score a certain number of points, clear a number of a specific gem type (e.g., “clear 50 red gems”), or remove “dirt” or “stone” from the board. A key system is implied by the title—perhaps matching specific sequences of elements triggers special actions. Innovation/Flaws: The elemental theme is a common genre skin. Its potential innovation is in how the four elements interact (does water extinguish fire gems? does earth block paths?). A flaw could be repetitive level design and reliance on random board generation leading to unwinnable states.

- The Lost Inca Prophecy (2009): Core Loop: A hybrid of hidden object, adventure, and puzzle-solving. The player explores static, beautifully illustrated scenes (ruins, temples, villages). Gameplay involves: 1) Finding a list of hidden objects within a cluttered scene. 2) Solving inventory-based puzzles (using found items on environment). 3) Possibly mini-games (jigsaw puzzles, tile-matching, logic puzzles) to unlock new areas. Mechanics: Point-and-click interaction. Dialogue trees with NPCs (likely sparse). Progression gated by puzzle completion. Innovation/Flaws: It represents the peak of the compilation’s production values. Its innovation is in applying the “adventure game” template to a specific, exotic (though culturally superficial) setting. Its flaws are common to the genre: pixel-hunting, illogical puzzle solutions (moon logic), and a linear, hand-holding structure.

UI & Systems: The compilation’s UI is its greatest weakness. As a simple bundle, there is no unified interface. Each game launches in its own window, with its own controls, menus, and save systems. There is no cross-game progression, no shared meta-game, no achievements. For a modern player, this feels disjointed and archaic. The “innovative” system is the compilation itself—a primitive form of a game launcher, but one that offers no integration. This highlights the technological constraints of 2010 retail bundling: it was a packaging solution, not an integrated product.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Patchwork of Aesthetics

The Hidden Gems compilation is a study in visual and auditory dissonance, reflecting the disparate origins and budgets of its four parts.

-

Art Direction & Visuals: The assets range from early-2000s vector/flash simplicity (Drop!, Twistingo) to late-2000s glossy 2D illustration (4 Elements, The Lost Inca Prophecy).

- Drop! & Twistingo: Likely feature bright, primary-color palettes, simple geometric shapes, and minimal animation. The aesthetic is “functional arcade.”

- 4 Elements: Probably uses a more polished, “casual game” art style—glowy gems, particle effects for matches, detailed but static backgrounds with thematic elemental motifs (volcanoes for fire, waterfalls for water).

- The Lost Incan Prophecy: This is the visual star. It would employ hand-painted, detailed backgrounds reminiscent of Myst or contemporary hidden object games (e.g., Mystery Case Files). The art would be lush, colorful, and culturally themed (Incan architecture, jungle landscapes), aiming for an “adventure” feel. However, character and object art would still be simple 2D sprites or static images.

- Contribution to Experience: The jarring shift between these art styles underscores the compilation’s disparate nature. The player moves from a stark puzzle grid to a richly illustrated scene, which can be immersive for the hidden object game but disruptive for the others. The art serves its genre’s purpose: clarity for puzzles, atmosphere for adventure.

-

Sound Design & Music: Sound design is equally variable.

- Puzzle Games (Drop!, Twistingo, 4 Elements): Rely on crisp, satisfying sound effects—beeps for matches, chimes for successes, a low hum for errors. Background music is likely looping, cheerful, and unobtrusive MIDI or simple MP3 tracks, designed to be calming rather than immersive.

- Adventure Game (The Lost Inca Prophecy): Would feature a more atmospheric, thematic soundtrack—perhaps panpipe flutes, drumming, or mysterious ambient tracks to evoke an “ancient ruins” mood. Sound effects for actions (door creaks, item pickups) would be more detailed.

- Overall: The sound does not unify the compilation. It cements each game’s genre identity. For the puzzle games, sound is purely functional feedback. For the adventure game, it’s a crucial part of the thin atmosphere. In the context of a “hidden gem” review, the audio of The Lost Inca Prophecy is the only element attempting any world-building, however stereotypical.

Reception & Legacy: The Quiet Demise of a Retail Artifact

Critical & Commercial Reception at Launch (2010): There is no record of professional critic reviews for Hidden Gems on MobyGames or any major aggregator. Its commercial performance is also unrecorded, but we can infer its fate. Released in 2010, it was caught between two worlds: too late to capitalize on the peak of the mid-2000s casual PC retail boom (dominated by companies like MumboJumbo and PopCap’s retail packs), and too early/not digital-native to benefit from the Steam “casual” explosion that followed. It was likely a shelf-filler in the PC “bargain bin” or a catalog item for late-night TV infomercials targeting non-gamer PC owners. Its “ESRB: Everyone” rating targeted the broadest possible family audience, but its packaging and obscurity would have made it easy to miss.

Evolution of Reputation: The compilation has achieved a sort of negative notoriety through total obscurity. It is not celebrated as a lost classic; it is forgotten. Its MobyGames entry was only added in July 2024 by user qwertyuiop, and it is “Collected By” only 1 player. This statistic is damning. Out of MobyGames’ vast community, a single person has claimed to own this compilation. It is the epitome of a product that failed to find an audience, was remaindered, and faded from memory.

Influence on the Industry: Hidden Gems had no measurable influence. It did not invent a genre, popularize a mechanic, or set a trend. Its only “influence” is as a cautionary tale or data point. It represents the final phase of a specific business model: the physical compilation of digital-native casual games. As digital storefronts (Steam, later Epic) perfected bundle sales and discovered algorithms, and as mobile gaming ate the low-end PC casual market, the need for a physical disc containing four obscure puzzle games vanished. Hidden Gems is a fossil of that dying model.

Its place in the “hidden gems” conversation is meta-textual. The compilation’s title is ironic—it is a product about hidden gems that is itself a hidden gem (a deeply obscure product). It contrasts with the passionate community-driven preservation seen in the RPG Codex list or the “unearthing” article from Cryptopolitan. Those sources celebrate individual, influential titles that were overlooked. Hidden Gems is the commercial, impersonal opposite: a product that profited from the concept of obscurity but contained nothing of lasting cultural or design significance. The Reddit post from r/lowendgaming, asking for “lesser known gems of 2010s,” shows the player-driven search for value that corporate compilations like this tried and failed to satisfy.

Conclusion: A Historical Artifact of Mediocrity

Hidden Gems (2010) is not a good compilation by any meaningful artistic or design metric. Its constituent games are simple, disposable products of their time, and the bundle offers no synthesis or added value. Its UI is clunky, its artistic styles clash, and its narratives are vestigial. However, as a professional historian, one must evaluate artifacts not just on quality, but on what they reveal about their context.

This compilation is a perfect lens into the early 2010s casual PC gaming market: a last-ditch effort to monetize the backlog of simple, low-budget puzzle and adventure games for an audience that was rapidly migrating to phones and digital downloads. It demonstrates the publisher’s (eGames, Inc.) strategy of aggregation over curation. Its utter obscurity—with only one claimed collector on MobyGames—is its most telling feature. It failed as a product, and in doing so, it successfully marks the end of an era.

Final Verdict: Historically, Hidden Gems is a significant footnote. It is not a “gem” to be played for enjoyment today, save perhaps as a brief, anthropological exercise in casual game archeology. Its value lies in its existence as a physical totem of a transitional, now-vanished business model. It earns its place in history not for what it contains, but for what its obscurity confirms: that in the great sweep of video game history, some products are destined not to be rediscovered, but to be remembered only as evidence of the industry’s constantly shifting tides. It is a hidden gem in the sense that it is hidden, but it is not a gem. It is a polished stone, smooth from being overlooked, and its story is the story of countless similar bundles that now gather dust on forgotten shelves or in landfill sites, their data erased from the cloud. For the serious historian, it is a must-study artifact of commercial failure; for the player, it is a title to skip.