- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Small Fry Studios

- Developer: Small Fry Studios

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade

- Setting: North America

- Average Score: 84/100

Description

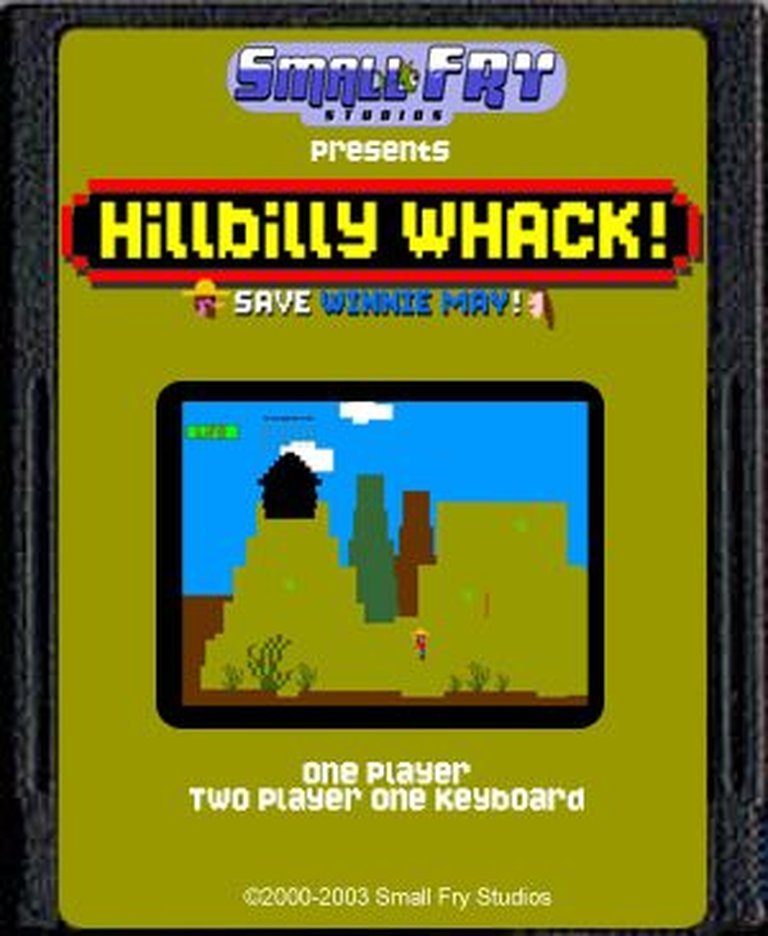

Hillbilly Whack! is a 2003 arcade-style action game where players take on the role of Samuel Jones, a hillbilly on a quest to reclaim his sweetheart Winnie May from the evil Clem. The game features classic Atari-inspired graphics, bluegrass/techno music, and a two-player mode where hillbillies compete to collect boards and rebuild their shack, two-seater, and moonshine still.

Hillbilly Whack! Free Download

Hillbilly Whack! Guides & Walkthroughs

Hillbilly Whack! Cheats & Codes

PC

Enter codes at the single player sub menu. Codes are also present on the level instructions screen.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| pigpede | Unlocks level 2 |

| yetis | Unlocks level 3 |

| twoseater | Unlocks level 4 |

| caverns | Unlocks level 5 |

| forest | Unlocks level 6 |

| swamp | Unlocks level 7 |

| chickens | Unlocks level 8 |

| factory | Unlocks level 9 |

| rooster | Unlocks level 10 |

| maze | Unlocks level 11 |

| clem | Unlocks level 12 |

| endmovie | Unlocks level 13 |

| bonus | Unlocks level 14 |

Hillbilly Whack!: Review

In the pantheon of obscure digital curiosities, few titles capture the singular blend of absurdity, nostalgia, and unbridled charm quite like Hillbilly Whack! Released in the autumn of 2003 by Small Fry Studios, this freeware arcade-platformer arrived during an era dominated by sprawling 3D adventures and cinematic epics. Yet, it carved its own peculiar niche through a deliberate, unapologetic embrace of retro simplicity and hillbilly hijinks. More than a mere game, Hillbilly Whack! is a time capsule—a digital artifact celebrating the pixelated aesthetics and frantic gameplay of the Atari age, filtered through the lens of Appalachian folklore. Its legacy, while modest, endures as a testament to the enduring appeal of accessible, character-driven experiences in an increasingly complex industry. This review deconstructs the game’s genesis, gameplay, artistry, and cultural footprint, arguing that its true significance lies not in technical prowess or narrative depth, but in its unwavering commitment to pure, unpretentious fun.

Development History & Context

The Vision of Small Fry Studios

Hillbilly Whack! emerged from the independent development collective Small Fry Studios, a boutique team whose portfolio, as documented on MobyGames, reveals a penchant for small-scale, idiosyncratic projects. Led by producer and artist-designer Jay Brewer, supported by programmer Russell Miner and musicians John Magee and Luke Stark, the studio crafted a game born from a singular, unambiguous vision: to distill the essence of 1980s arcade action into a cohesive, hillbilly-themed experience. The sources consistently emphasize Brewer’s central role, crediting him as both the creative force behind the game’s aesthetic and the business decision to release it as freeware—a bold move in 2003 that prioritized accessibility over profit in an increasingly commercialized market.

Technological Constraints and Creative Solutions

Developed for both Windows and Mac OS X (with a simultaneous release on November 7, 2003), Hillbilly Whack! operated within the technological confines of the early 2000s. The game’s “classic Atari-Age graphics,” as noted in its official description, were not merely stylistic choices but pragmatic responses to developer constraints. Using fixed/flip-screen visuals and a side-scrolling perspective optimized for low-end systems (minimum specs: Pentium III/PowerPC G4, 128MB RAM, DirectX 7.0), Small Fry Studios achieved remarkable efficiency. The decision to employ bitmap art and chunky pixel animations allowed the game to run smoothly on modest hardware, embodying the “make do” ethos of its hillbilly protagonists. This technical minimalism extended to its development cycle; the small team of four credits (per MobyGames) suggests a lean, agile process focused on core gameplay polish over feature creep.

The Gaming Landscape of 2003

Hillbilly Whack! materialized in a transitional period for gaming. Major releases like Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic and Beyond Good & Evil showcased the industry’s shift toward narrative depth and graphical fidelity. Against this backdrop, Small Fry Studios’ deliberately retro title stood in stark contrast. Its release as freeware on platforms like Tucows and its promotion via niche outlets like Inside Mac Games reveal a strategy targeting audiences disillusioned with AAA bloat or craving accessible, local multiplayer. The game’s two-player, one-keyboard mode—a direct throwback to arcade cabinets—was a particularly astute nod to a bygone era, offering immediate social engagement in a market increasingly dominated by online play. While it lacked the marketing budget of contemporaries, its grassroots distribution ensured survival as a cherished oddity among retro enthusiasts.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Plot: A Backwoods Odyssey

The narrative of Hillbilly Whack! is distilled to its Appalachian essence: “a hillbilly named Samuel Jones who has lost his sweetheart Winnie May to an evil hillbilly named Clem.” This setup, repeated across sources like MobyGames and SocksCap64, is pure fairy-tale simplicity. Rescue Winne May, reclaim your honor, and rebuild your life—literalized through the collection of boards for your shack, two-seater, and moonshine still. The absence of cinematic cutscenes or complex dialogue forces players to infer the story through environmental cues and gameplay objectives. Clem’s villainy is never elaborated beyond “evil,” rendering him a one-dimensional antagonist, while Samuel’s motivations remain tethered to primal urges: love, property, and sustenance. The narrative arc thus mirrors the cyclical nature of Appalachian folklore—a hero’s journey stripped to its bare bones.

Characters and Dialogue: Stereotypes as Archetypes

Characterization in Hillbilly Whack! leans heavily on hillbilly stereotypes, but these function as deliberate archetypes rather than caricatures. Samuel Jones embodies the noble-yet-resourceful frontiersman, his silent protagonist status allowing players to project earnestness onto his quest. Winnie May exists purely as a damsel in distress, her absence driving the plot but offering no agency. Clem, the “evil” foil, represents unchecked greed and lawlessness—a thematic duality to Samuel’s community-focused rebuilding. The lack of voiced dialogue (standard for the era’s freeware) shifts focus to contextual humor: the sight of drunken chickens or a moonshine-powered Samuel evokes chuckles without the need for exposition. These elements collectively celebrate, rather than mock, hillbilly culture, positioning its quirks as virtues in a world obsessed with sophistication.

Thematic Resonance: Rebirth and Resourcefulness

Beneath its cartoonish surface, the game explores potent themes of rebirth and resourcefulness. The act of collecting boards to rebuild one’s home, vehicle, and livelihood is a metaphor for resilience—a recurring motif in Appalachian narratives. The moonshine mechanic, described in sources like Inside Mac Games as a tool to “make tasks easier,” symbolizes the ingenuity born from scarcity; it’s a temporary boost, a liquid catalyst for overcoming adversity. The animal antagonists—goats, pigs, cows, and bears—are not merely obstacles but symbols of untamed wilderness, forcing Samuel to adapt and improvise. Even the two-player mode, where players “whack” each other for boards, reframes cooperation as competitive camaraderie, echoing communal bonds forged through shared struggle. These themes, though delivered through simple gameplay, lend the game an unexpected emotional weight.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Collect, Build, Whack

The gameplay loop is a masterclass in arcade clarity. Players control Samuel Jones across “more than 13 levels” (per Inside Mac Games), each demanding collection of boards—the currency for reconstruction. Progression is tied to rebuilding key assets: the shack (safe haven), the two-seater (mobility), and the moonshine still (power-up source). This creates a satisfying feedback loop; each board collected inches the player toward tangible, visible upgrades, fostering a sense of accomplishment. The fixed-screen levels, as noted in MobyGames’ specs, ensure bite-sized sessions ideal for quick play, while the direct control interface prioritizes responsiveness.

Combat and Encounters: Chaotic and Consequential

Combat is an exercise in controlled chaos. Samuel engages in fisticuffs with a menagerie of farm animals and forest fauna, each enemy requiring distinct tactics. Chickens, for instance, become “drunken” after moonshine consumption, their erratic movement patterns adding unpredictability. Bears present a brute-force challenge demanding evasion and timing. The lack of complex combos keeps the action accessible, but the risk/reward of close-quarters fighting maintains tension. Environmental hazards—like stampeding goats or aggressive pigs—demand situational awareness, turning simple traversal into a puzzle of positioning. The outcome of these encounters isn’t just survival; it’s resource denial, as enemies can destroy boards, raising the stakes of every skirmish.

Character Progression: Power Through Moonshine

Progression is non-linear and ephemeral, tied entirely to the moonshine still. By collecting boards to rebuild it, players gain access to “moonshine,” a temporary power-up imbuing Samuel with superhuman speed and strength. This isn’t a leveling system but a situational tool, encouraging strategic resource management. Do you moonshine to rush through a difficult section or save it for a boss fight? This lateral progression emphasizes adaptability over grind. The two-player mode amplifies this, turning board collection into a competitive race where moonshine becomes a double-edged sword—boosting your board count but leaving you vulnerable to attack. The asymmetry between single-player goal (rescue Winnie May) and multiplayer goal (hoard boards) offers surprising replayability.

UI and Control: Functional and Forgiven

The user interface prioritizes function over flair. A minimalist HUD displays board count and still status, while keyboard controls (WASD/movement, Space/action) are crisp and responsive, as documented in SocksCap64’s specs. The fixed-screen design eliminates camera issues, focusing attention on the action. While lacking the polish of commercial titles, the UI serves its purpose without obstruction. One minor flaw noted in player discussions (via Reddit and Giant Bomb) is the occasional difficulty in distinguishing between collectible boards and environmental clutter, a legacy of the game’s low-resolution sprites. Yet this flaw is forgivable, adding to the game’s rustic charm.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Setting: The Appalachian Backdrop

The game’s setting—a stylized, exaggerated version of rural North America—functions as a character in its own right. Levels transition from dilapidated shacks to muddy pastures and dense forests, each environment steeped in hillbilly iconography. The shack, for instance, isn’t just a building but a symbol of displaced domesticity, its reconstruction a narrative of homecoming. The two-seater represents freedom, while the moonshine still embodies self-sufficiency. These landmarks anchor the gameplay in a tangible, lived-in world, even as the art style abstracts reality. The absence of overtly political or social commentary allows the setting to exist as a mythic space, a digital approximation of “hillbilly heaven” where struggles are primal and solutions are simple.

Art Direction: Pixelated Folk Art

“Classic Atari-Age graphics” is not just a descriptor but a manifesto. The art, crafted by Jay Brewer, employs bold primary colors, blocky character sprites, and detailed backgrounds that evoke 8-bit-era platformers. Samuel’s overalls and straw hat are rendered in recognizable, if exaggerated, detail, while enemies like goats and cows possess a chunky, endearing menace. The flip-screen aesthetic, per MobyGames, creates a diorama-like effect, with each screen acting as a self-contained tableau. This style choice is deeply intentional; it rejects realism for a stylized folk-art aesthetic, celebrating the game’s hillbilly roots through visual nostalgia. Even today, the art holds a certain charm, its limitations fostering a unique visual identity in an era of homogenized 3D graphics.

Sound Design: Banjos and Bitcrunches

The audio landscape is a dichotomy of old and new. Bluegrass fiddles and banjos provide the melodic foundation, evoking Appalachian tradition, while synthesized techno beats—described in the official blurb—inject a modern, arcade-like energy. This fusion mirrors the game’s thematic blend of heritage and chaos. Sound effects are equally distinct: the thud of Samuel’s fist, the cluck of a chicken, the twang of a banjo riff. As preserved in the Internet Archive’s Tucows entry, these elements create a soundscape that is both immersive and anachronistic. The moonshine mechanic, for instance, is accompanied by a distorted, sped-up musical cue, mimicking the intoxicating effect on gameplay. While not technically sophisticated, the audio is inseparable from the game’s identity, turning simple actions into sensory events.

Atmosphere: Nostalgia and Absurdity

The art and sound converge to cultivate an atmosphere of unbridled absurdity. There’s a deliberate disconnect between the game’s bucolic setting and its frantic action—dodging drunken chickens or fending off bears feels comically out of place. Yet this dissonance is the point. The atmosphere isn’t one of realism but of cartoonish hyperbole, where moonshine-induced super feats are as natural as a sunrise. This tone, amplified by the cheerful brio of the soundtrack, makes even frustrating moments feel playful. It’s a world where failure is never punitive, only humorous—a digital playground where the hillbilly ethos of “gumption” reigns supreme.

Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception: A Cult Hit in the Making

Upon release in November 2003, Hillbilly Whack! garnered minimal mainstream attention, typical of freeware titles from small studios. Coverage was largely confined to niche outlets like Inside Mac Games, which praised its “old school fun” and two-player mode, and download hubs like Tucows. Critical reviews were scarce, with MobyGames aggregating only a single player rating of 4.2/5 (as of 2025), reflecting modest but positive player reception. The game’s freeware status likely deterred professional critics, while its retro aesthetic may have seemed outdated compared to contemporary blockbusters. Yet, among arcade purists and Mac gaming communities, it developed a cult following. Its appeal lay in its accessibility and multiplayer charm, offering instant gratification in an era of bloated RPGs.

Long-Term Reputation: A Curio of Digital Archaeology

Over two decades, Hillbilly Whack!’s reputation has evolved from a forgotten title to a cherished artifact. Preserved on platforms like the Internet Archive and discussed on forums like Reddit, it’s now studied as a case study in indie resilience. Its freeware model is lauded as ahead of its time, predating modern indie trends. Players on sites like SocksCap64 reminisce about its “nostalgic” appeal, while Giant Bomb’s user forums debate its place in the arcade revival canon. Critically, it’s admired for its cohesive vision—a rare quality in small-scale games. Yet its legacy is modest; it never spawned sequels or imitators, remaining a singular footnote. As noted in Game Classification, its audience (ages 12-25) skewed toward casual players, limiting its cultural penetration.

Influence and Industry Impact: Niche but Noteworthy

While Hillbilly Whack! didn’t revolutionize gaming, its influence is subtly woven into the fabric of indie history. Its emphasis on local multiplayer and retro aesthetics foreshadowed the 2010s indie boom, where games like TowerFall celebrated similar strengths. The game’s success as freeware also demonstrated the viability of alternative distribution models in a pre-Steam era. Thematically, its unironic embrace of regional folklore (hillbilly culture) paved the way for titles like Untitled Goose Game and Kentucky Route Zero, which explore marginalized settings with sincerity. Yet its most significant legacy is preservation: by surviving on archives, it serves as a reminder of gaming’s democratic potential—how passion projects, unfunded and unpolished, can still leave a mark.

Conclusion

Hillbilly Whack! is a paradox: a game defined by its limitations yet elevated by its ambition. In an industry obsessed with scale and spectacle, Small Fry Studios delivered a compact, self-contained experience where every pixel, board, and moonshine swig serves a purpose. Its narrative, though skeletal, resonates through thematic clarity; its gameplay, though simple, achieves lasting satisfaction through tight mechanics and local camaraderie; its art and sound, though retro, cohere into a singular, charming identity. The game’s legacy isn’t measured in sales or acclaim, but in its preservation as a testament to gaming’s grassroots spirit—a freeware gem that thrived on passion, not polish.

To dismiss Hillbilly Whack! as a mere novelty would be to overlook its quiet brilliance. It is a love letter to the arcade age, filtered through the unique lens of Appalachian folklore, and a reminder that the most memorable games aren’t always the most complex. They are the ones that capture the pure, unadulterated joy of play. For historians, it’s a valuable artifact of the early-2000s indie landscape; for players, it’s a time machine to an era of simpler pleasures. In the final reckoning, Hillbilly Whack! may not be a masterpiece, but it is a masterpiece of its kind—an enduring, irreplaceable piece of digital Americana.