- Release Year: 1994

- Platforms: DOS, Linux, Macintosh, Windows

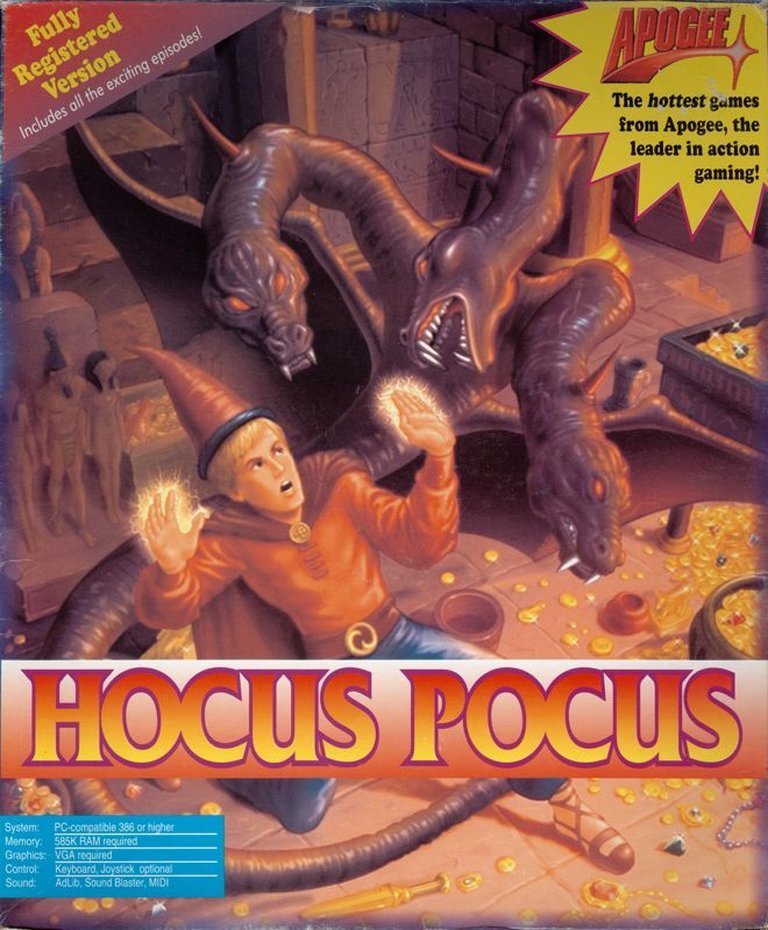

- Publisher: 3D Realms Entertainment, Inc., Apogee Software, Ltd., U.S. Gold Ltd., WizardWorks Group, Inc.

- Developer: Apogee Software, Ltd., Moonlite Software

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Collectibles, Elevators, Jumping, Key collection, Platformer, Power-ups, Shooter, Switches, Teleportation

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 69/100

Description

Hocus Pocus is a 1994 side-scrolling platformer where you play as a young magician’s apprentice on a quest. To achieve his twin goals of joining the Council of Wizards and marrying his sweetheart, Popopa, Hocus must embark on a dangerous journey through the fantasy land of Lattice. He must run, jump, and climb through various levels, battling monsters and collecting magical crystals for the wizard chief Terexin. Along the way, he can collect potions that restore health or grant special powers like a super-jump or a laser shot to aid in his adventure.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Get Hocus Pocus

Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

godmindedgaming.com : The combat is a bit lackluster, filling the game with unnecessary bottlenecks.

mobygames.com (69/100): Overall, it’s a good game, however without any originality.

mobygames.com : Overall, it’s a good game, however without any originality.

Hocus Pocus: A Forgotten Gem in the Shadow of Giants

In the vast, pixelated pantheon of 1990s shareware platformers, where titans like Commander Keen and Duke Nukem reigned supreme, many competent, charming games were destined to become footnotes. Hocus Pocus, released in 1994 by Moonlite Software and published by the legendary Apogee Software, is one such title—a game of undeniable technical polish and whimsical character that was, perhaps unfairly, cast into the shadow of its publisher’s own colossal hit, Raptor: Call of the Shadows. This review will delve into the creation, mechanics, and legacy of a game that represents both the pinnacle and the peril of the Apogee shareware model: a beautifully crafted, if sometimes derivative, experience that never quite got its moment in the sun.

Development History & Context

The story of Hocus Pocus is inextricably linked to the ambition of one man, Mike Voss, and the powerhouse publishing model of Apogee Software. In the early 1990s, Voss, operating under the banner Moonlite Software, was not a career game developer. Inspired by the success of Apogee’s shareware titles and an article detailing the publisher’s receipt of hundreds of daily orders, he dipped his toes into the market. His first creation was Clyde’s Adventure (1992), a simple side-scroller where the protagonist used a wand to navigate maze-like castles. While only a modest success, it was enough to catch the eye of Apogee founder Scott Miller.

Apogee’s business model was a beacon for independent developers: they handled publishing and distribution while allowing creators to retain the rights to their games and paying them royalties. This appealed to Voss, who signed on to develop his next project. Hocus Pocus was conceived as a spiritual successor to Clyde’s Adventure, but with a crucial shift in gameplay inspired by Apogee’s own Duke Nukem—exchanging a puzzle-solving wand for a projectile-firing spell.

Development, however, was hampered by technical limitations. Voss was reportedly working on a 6-inch black-and-white monitor for a significant portion of the process after his color monitor failed. The initial builds were visually rough. It was here that Apogee’s value as a publisher became evident. They brought in Cygnus Multimedia Productions (distinct from Cygnus Studios, developers of Raptor) to overhaul the game’s visuals. The transformation was striking; Cygnus replaced the rudimentary sprites and tiles with lush, hand-painted-looking backgrounds and polished character art, elevating the game into one of the most visually appealing VGA titles of 1994.

The audio department received a similar upgrade. Rob Wallace of Wallace Music & Sound Inc. and Jeff Gatlin composed the MIDI score, while Jim Dosé handled the sound system, supporting premium sound cards like the Sound Blaster and Gravis Ultrasound. This professional touch gave the game an aural sheen far beyond Voss’s previous work.

Tragically for Hocus Pocus, its release on June 1, 1994, was strategically doomed. Just two months prior, Apogee had released Raptor: Call of the Shadows, a smash-hit vertical scroller that became the company’s primary marketing focus. As Voss would later lament, he saw “full page ads in gaming magazines for Raptor. I saw no advertising for Hocus Pocus.” The game was effectively sent to die, becoming a bargain-bin title almost overnight. Following Hocus Pocus and work on Clyde’s Revenge, Mike Voss left the game industry entirely, his bright but brief career a testament to the fickle nature of the shareware era.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The plot of Hocus Pocus is a classic, straightforward fantasy quest, delivered with a lighthearted, almost self-aware tone. The player controls the eponymous Hocus Pocus, a young wizard apprentice with two simple goals: to gain entry into the prestigious Council of Wizards and to marry his sweetheart, Popopa (who also happens to be the daughter of the council’s leader, Terexin). The grumpy, Gandalf-esque Terexin tasks Hocus with a seemingly impossible quest: to journey across the Land of Lattice and gather magical crystals from four distinct, monster-infested realms.

The narrative structure is episodic, a hallmark of the shareware model:

* Episode 1: Defeat the Mad Monks of MellenWah.

* Episode 2: Vanquish the Tree Demons.

* Episode 3:

* Overcome the Gray Dragons of Higgendom.

* Episode 4: Confront the evil wizard Trolodon, whose grievance with the council originated from a “Silly Reason for War”—a disagreement over what china to use at dinner.

The story is primarily advanced through text interludes between episodes and through the holographic appearances of Terexin within levels. These holograms provide a dynamic, if sometimes bizarre, narrative device. Terexin’s dialogue ranges from genuine puzzle-solving advice to cryptic non-sequiturs, such as boasting about the 67 years it took him to grow his beard. This injects a dose of personality into what could have been a generic mentor figure.

Interestingly, Terexin undergoes subtle Character Development. He begins deeply skeptical of Hocus’s abilities, but as the apprentice succeeds, his demeanor softens into one of respect and encouragement—until the final victory over Trolodon, which briefly returns him to a state of sputtering disbelief. This arc, minor as it is, was uncommon for platformers of the era.

Thematically, the game is a light exploration of perseverance and proving one’s worth. However, its treatment of its female character, Popopa, is a product of its time. She exists purely as a prize to be won, a narrative trophy with no agency, a point that stands out awkwardly against the otherwise charming and inoffensive fantasy setting. The game also includes a questionable joke about the all-male wizard council’s eagerness to “study” the “Beautiful Amazon Tribes Before the Time of Clothes Era,” a moment that clashes with its family-friendly aesthetic.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Hocus Pocus is a classic 2D platformer with a primary objective: collect every magic crystal in a level to proceed. The player guides Hocus through 36 levels (9 per episode) of increasingly complex mazes, navigating platforms, avoiding environmental hazards like spikes and lava, and dispatching a menagerie of enemies.

Core Mechanics & Controls:

* Movement & Combat: Controls are simple and responsive. Hocus runs, jumps, and fires a default, slow-moving magic projectile with infinite ammunition. The jumping physics are precise, a critical element for the game’s often demanding platforming sections.

* The Potion System: This is the game’s key innovation. Scattered throughout levels are potions that grant temporary power-ups:

* Rapid Fire: Dramatically increases the rate of fire, essential for dealing with enemy hordes and bosses.

* Laser Shot: Fires three powerful shots that pierce through enemies and can even one-hit-kill bosses if timed correctly.

* High Jump: Grants a temporary super-jump to reach otherwise inaccessible areas.

* Health Potion: Restores 10% of Hocus’s health.

* Warp Potion: Teleports Hocus to a secret room, often filled with treasure.

* Exploration & Puzzles: Levels are non-linear and encourage exploration. Players must find silver and gold keys to unlock corresponding doors, flip switches to make platforms appear, and use elevators to navigate vertical shafts. Some blocks can be destroyed by shooting them, revealing secrets. The game features a robust 100% Completion system, rewarding players with bonus points for collecting all treasures (rubies, diamonds, crowns, etc.) in a level.

Enemy & Boss Design:

This is one of the game’s most critiqued areas. While the enemy sprites are varied and thematic—ranging from giant mushrooms and crocodiles to mummies, penguins, and dragons—their artificial intelligence is rudimentary. Enemies adhere to one of three basic patterns: “walk-and-shoot,” “fly-and-shoot,” or “just-walk.” This lack of variety can make combat feel repetitive, especially in long, enemy-dense corridors.

The bosses, however, are a highlight. Each episode culminates in a unique boss fight that requires pattern recognition and persistence. The final boss, the wizard Trolodon, is a multi-stage affair where he retreats to a new floor after taking significant damage. A notable flaw is that touching any boss results in an instant One-Hit Kill, a punishing mechanic that can lead to frustration.

Flaws and Quirks:

* Unintentionally Unwinnable States: Poorly placed elevators or prematurely used warp potions can soft-lock the player, forcing a level restart.

* Cheat Code Glitches: The game was known to randomly activate cheat codes, such as granting the player all keys or permanent rapid fire, which could disrupt the intended challenge.

* Repetitive Design: As noted by contemporary critics, level tilesets and music tracks are reused, particularly between the Egyptian and Arabian-themed areas, leading to a sense of visual and aural repetition over the 36-level journey.

World-Building, Art & Sound

If Hocus Pocus has one undeniable, lasting strength, it is its presentation. The game is a visual and auditory treat that stands the test of time.

Visual Design:

The work of Cygnus Multimedia Productions is the star of the show. Utilizing 256-color VGA, the game features exceptionally detailed, pre-rendered backgrounds with a remarkable depth achieved through parallax scrolling. Each of the game’s thematic areas is distinct and immersive:

* Episode 1: Features castles with giant, decorative mushrooms and icy palaces with treacherous spikes.

* Episode 2: Presents Egyptian pyramids with hieroglyphics and mummies, followed by ominous, enchanted forests with attacking tree-people (a clear parody of Tolkien’s Ents).

* Episode 3 & 4: Venture into spooky castles, prehistoric lands with dinosaurs, and the final, foreboding towers of Trolodon.

The sprites for Hocus and the enemies are well-animated and full of character. The final cutscene, an Unexpected Art Upgrade Moment, presents a detailed, almost painterly image of Hocus and Popopa’s “Sealed with a Kiss,” a significant step up from the in-game visuals and a rewarding capstone.

Sound Design:

The MIDI soundtrack by Rob Wallace and Jeff Gatlin is superb. It dynamically matches the level themes, from cheerful and adventurous melodies in the early stages to spooky, atmospheric tunes in the later, more dangerous areas. When played through a supported sound card like the Gravis Ultrasound, the music is rich and impactful. Sound effects are serviceable and “magical,” though some contemporary reviewers found them annoying or too quiet. The overall audio package, however, is a significant contributor to the game’s charming atmosphere.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Hocus Pocus received a mixed-to-positive critical reception, earning an average score of 69% from professional critics. Praise was consistently directed at its graphics, smooth controls, and polished presentation. Techtite awarded it a perfect score, calling it “one of my favorite of all games in ’94,” specifically highlighting the parallax scrolling and music. Conversely, critics like The Retro Spirit (42%) pointed to “imprecise controls” and “poor level design,” while others bemoaned its repetitive nature and lack of originality compared to contemporaries like Jazz Jackrabbit.

Player reviews, as archived on MobyGames, reflect a similar dichotomy. Many remember it fondly as a beautiful, fun, and accessible platformer, perfect for beginners. Others criticized its simplistic enemy AI, uneven difficulty, and the feeling that it was a “solid game without anything spectacular.”

The legacy of Hocus Pocus is complex. Commercially, it was overshadowed and is remembered today as a cult classic rather than a genre-defining hit. Its influence on the industry is minimal, but its story is a poignant case study in the realities of 1990s game publishing. It exemplifies the high level of quality that could be achieved by a small developer under the wing of a publisher like Apogee, while also serving as a cautionary tale about the risks of being a lower-priority title in a crowded release schedule.

Its legacy persists through digital storefronts like GOG.com and Steam, where it has been re-released, allowing a new generation of players to discover its unique charms. It is also included in compilations like the 3D Realms Anthology, ensuring its preservation as a notable, if not revolutionary, entry in the history of DOS gaming.

Conclusion

Hocus Pocus is a game of endearing contrasts. It is a product of immense technical polish applied to a fundamentally conventional design. Its beautiful, parallax-scrolled worlds and charming audio are let down by repetitive combat and occasionally frustrating design choices. It is the story of a developer’s dream realized, only to be eclipsed by the very machine that enabled it.

To play Hocus Pocus today is to experience a beautifully preserved artifact from the golden age of shareware. It may not possess the groundbreaking innovation of Commander Keen or the blistering pace of Jazz Jackrabbit, but it executes the core tenets of the 2D platformer with competence and style. Its final verdict is that of a hidden gem—flawed, perhaps forgotten by the masses, but beaming with a magical, pixelated heart that still resonates with those who take the time to seek it out. It is, in every sense, a worthy and endearing chapter in the storied history of Apogee Software.