- Release Year: 2015

- Platforms: Browser, Linux, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Empire Directory

- Developer: Empire Directory

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: MMO

- Gameplay: Colonization, Conquest, Diplomacy, Exploration, Fleet Management, Trading

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 85/100

Description

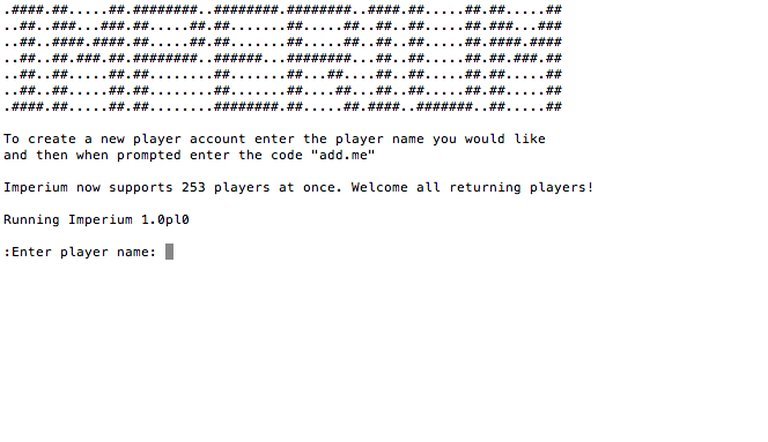

Imperium is a massively multiplayer online strategy game set in a sci-fi universe, where up to 253 players engage in persistent intergalactic conquest and exploration. Starting from their chosen race’s home planet with a single starship, players colonize planets, form treaties, trade resources, and compete in a real-time or turn-based world that typically lasts for months, using a text-based interface accessible via Telnet or enhanced with visual frontends.

Where to Buy Imperium

PC

Imperium Free Download

Imperium Reviews & Reception

gameinformer.com (85/100): Stylish action games have evolved a lot in recent years, and this release skillfully straddles the line between new and old.

Imperium (2015): A Text-Based Galaxy Forgotten – An Archaeological Review

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine

In the vast, ever-expanding cosmos of video game history, certain titles exist in a state of perpetual obscurity—known to a handful of dedicated archivists but absent from mainstream discourse. Imperium (MobyGames ID 73654), released on New Year’s Day 2015 by the enigmatic one-person studio Empire Directory, is precisely such a title. It is not a graphical powerhouse, nor a narrative milestone; it is a stubborn, persistent, and nearly invisible relic of the text-based MMO era, a game that chose to exist in the terminal rather than the GPU. This review posits that Imperium’s true significance lies not in its implementation but in its philosophical purity: it is a pure, unadulterated 4X strategy experience stripped of all visual spectacle, relying entirely on player imagination, textual description, and sociopolitical negotiation. Its legacy is that of a deliberate counterpoint to an industry increasingly obsessed with cinematic presentation, serving as a stark reminder that the essence of grand strategy can reside in nothing more than words on a screen.

Development History & Context: A One-Person Odyssey Against the Grain

The development history of Imperium is as cryptic as its interface. The sole credited creator is Marisa Giancarla, whose name appears on the Linux version credits and who added the game to MobyGames in July 2015. The only concrete technical trivia is that the game “was first developed for the Amiga,” a platform whose heyday was decades prior, suggesting either a long-gestating personal project or a direct port/adaptation of much older code. The choice of programming languages—C, Perl, and JavaScript for various clients—speaks to a pragmatic, cross-platform ethos, focusing on accessibility over graphical fidelity.

This context places Imperium in a specific technological and cultural moment: 2015. This was the era of the mainstream ascendance of the 4X board game Twilight Imperium (Fourth Edition released in 2017, but its third edition was already a cult phenomenon). The gaming landscape was saturated with visually sumptuous space operas like Elite: Dangerous and Star Citizen (in early, ambitious development). Against this tide, Imperium’s commitment to a Telnet-accessible, ASCII-friendly interface was radically anachronistic. It did not merely lack graphics; it rejected their necessity. The constraint was not a limitation but a stated design principle: “A computer does not need to support graphics.” This places Imperium in the lineage of MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons) and early BBS games like TradeWars 2002 or Legend of the Red Dragon, but applied to the grand scale of interstellar empire management. It was a game designed for the terminal purist, the sysadmin with a Telnet client, or anyone who believed that the mind’s eye is the most powerful renderer.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Empire is in the Mind

Imperium provides no authored narrative, no characters, no dialogue trees, and no scripted plot. Its “story” is entirely emergent and player-driven, generated through the interactions of up to 253 concurrent players in a persistent galaxy. This is the purest form of emergent narrative in strategy gaming.

The thematic core is explicitly laid out in its description: intergalactic conquest and exploration. Players begin as the sole representative of a chosen race on their homeworld with a single Class-A starship. The thematic questions are those of every 4X game: expansion vs. consolidation, diplomacy vs. domination, resource management vs. technological leapfrogging. However, Imperium forces these questions into a purely social and strategic arena. There are no pre-rendered cinematic moments depicting the horror of war; the horror is in the cold calculation of a treaty broken, the trade embargo imposed, or the fleet that arrives at your undefended colony.

The “race” selection is the only narrative hook, a brief descriptor that likely provides unique bonuses (as in all 4X games) and informs roleplay. The deeper narrative is the rise and fall of empires dictated entirely by player action. A game lasting “several months” allows for true geopolitical depth: alliances forged and shattered, betrayals that echo through the game’s lifecycle, and a player-become-Emperor whose reign is remembered by the community. The theme is absolute player sovereignty. The game provides the galaxy, the rules, and the tools; the players write the history. It is a sandbox where the sand is stars and the molds are diplomacy, war, and economics.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Elegance of Abstraction

Imperium’s gameplay is a masterclass in mechanical minimalism. From its sparse description, we can deconstruct a likely system inspired by classic 4X (Explore, Expand, Exploit, Exterminate) but filtered through a persistent, real-time/turn-based hybrid MMO structure.

- Core Loop & Pacing: The loop is persistent. The game world ticks forward in real-time, but player actions—movement, colonization, fleet production—likely operate on discrete “turns” or command cycles that resolve at set intervals, or perhaps are resolved asynchronously with cooldowns. The “several months” duration indicates a slow, deliberate pace where planning is paramount and immediate gratification is absent.

- Exploration & Colonization: Starting with a single ship, players must explore nearby planets. The system is likely procedurally generated or static but unknown. Colonization expands your fleet’s capacity and resource base. The text interface means planet descriptions are textual—a “Class-M planet, Earth-like, resource-rich” versus a “barren rock with trace minerals.” The imagination fills the gaps.

- Fleet Management: Expansion of your fleet is tied to colonized planets. Ship types (Class-A is mentioned; likely there are Class-B, C, etc., for different roles) are built from resources. A key abstraction is whether combat is deterministic (based on stats) or involves dice/randomness, as in traditional board games.

- Diplomacy & Economy: This is where Imperium likely shines. The ability to declare treaties and trade goods with other players and NPC races is its lifeblood. In a text-based environment, negotiation is pure text—a chat window or in-game messaging system becomes the treaty table. The economic system likely revolves around specific goods (“trade goods”) that are produced on planets and exchanged. The mention of “factions” or “races” having unique traits would make certain goods more plentiful or valuable, creating natural trade routes and dependencies.

- Command & Control: The interface limitation (80-column, upper/lower case) forces a command-line or menu-driven interaction. Players type or select commands:

MOVE 12.45 TO SECTOR G7,COLONIZE PLANET ALPHA-3,DECLARE NON-AGGRESSION PACT WITH PLAYER "VORTIGERN". This creates a feeling of being a starship captainor imperial administrator issuing orders to a distant fleet. - Innovation & Flaws: The primary innovation is its complete decoupling from graphical representation. It is a strategy game for the inner ear and mind. The flaw is the same: its extreme barrier to entry. Without visual feedback, map understanding must be built from textual coordinates and possibly ASCII maps (if frontends provide them). This limits its audience to a niche of dedicated, text-oriented strategists. The “253-player” capacity is a technical feat for a text game, but managing interactions with 252 other entities via text chat would be a social and logistical nightmare, potentially devolving into chaos without strong meta-community norms or in-game enforcement tools not mentioned in the source.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of Absence

Imperium’s world-building is a fascinating case study in implied setting. The source gives us zero details about the galaxy’s lore, the nature of the “races,” or the history of the conflict. The setting is sci-fi/futuristic by default, a blank canvas.

- Visual Direction: There is none. The base game is pure text. The art exists only in the player’s mind, fueled by sparse planetary descriptions and ship class names. The “various frontends” that implement “visual elements” are crucial. A good frontend might provide a hex-based star map with colored dots for fleets, bringing it visually closer to Twilight Imperium or Sins of a Solar Empire. A bad frontend is just a chat client with a map window. The visual experience is entirely dependent on the user’s choice of client, making the “game” itself a set of rules and data, and the “experience” a user-interface construct.

- Sound Design: The source is silent on audio. It is almost certainly silent or synth-limited. Any sound would come from the client or be entirely fan-modded. The experience is one of * reading and typing*, punctuated by the occasional system message chime from the client software.

- Atmosphere: The atmosphere is one of cold, bureaucratic distance. You are not a heroic pilot; you are a strategic node, a command line. The tension comes from the weight of a message appearing in your chat log: “Your colony on Proxima Centauri II has been shelled by the fleet of player ‘Khaos.’” The horror is textual. This creates a unique, cerebral, and lonely atmosphere compared to the cinematic spectacle of graphical 4X games.

Reception & Legacy: The Unreviewed and the Unremembered

The reception of Imperium is, by definition, non-existent in the recorded critical sphere. The MobyGames page, our primary source, shows:

* Moby Score: n/a

* Critic Reviews: “Be the first to add a critic review for this title!”

* Player Reviews: “Be the first to review this game!”

* Collected By: 2 players.

This is the epitome of a cult object with no cult. It has not been reviewed by any aggregated critic site listed in the sources (like OpenCritic or Game Informer’s 2015 lists). Its “legacy” is confined to:

1. Its place in the MobyGames database as a preserved artifact.

2. Its relationship to other games titled Imperium (1990, 1992, 2008, etc.), which are entirely separate entities with no shared lineage.

3. Its existence as a curiosity for historians of digital games, representing the tail end of the persistent, text-based MMO strategy genre that flourished in the 1990s (think LegendMUD, Kerensky, or Conquest) but was largely abandoned by the 2010s in favor of graphical clients.

Its influence is negligible. It did not inspire a genre revival. It did not spawn a community large enough to create the kind of vibrant modding scene seen in Twilight Imperium’s Tabletop Simulator adaptations. It is a dead end—a beautifully pure but ultimately isolated implementation of an idea whose time had passed.

Conclusion: A Monument to What Might Have Been

Imperium (2015) is a paradox. It is a professionally developed (by a single individual), cross-platform, massively multiplayer 4X strategy game that is virtually unknown and functionally unreviewed. Its thesis—that a galaxy-spanning strategy epic can thrive on text alone—is sound in theory but, in practice, was a solution in search of a problem in 2015. The audience for such a demanding, imagination-reliant experience had already migrated to richer graphical interfaces or to the more social, immediate arenas of MOBAs and FPSes.

Its place in video game history is not as a classic or an influence, but as a significant footnote: the last gasp of a specific design philosophy that prioritized strategic purity over sensory immersion. It stands in stark contrast to the contemporaneous boom in “legacy” board game adaptations and the rising tide of indie graphical titles. Where Twilight Imperium (the board game) achieved celebrated depth through lavish components, Imperium (the MMO) pursued that same depth through radical subtraction.

The final, definitive verdict is one of profound respect for its ambition and a melancholy acknowledgment of its impracticality. It is a perfect game for an audience of one—the developer who built it to satisfy a personal vision of galactic conquest without graphical compromise. For everyone else, it remains a fascinating artifact: a testament to the idea that the map is not the territory, and that sometimes, the most epic battles are fought not with polygons and shaders, but with commands typed into a silent terminal under the faint glow of a CRT monitor. It is not a lost classic; it is a preserved relic, and its quiet obscurity is perhaps the most accurate narrative its mechanics could have produced.