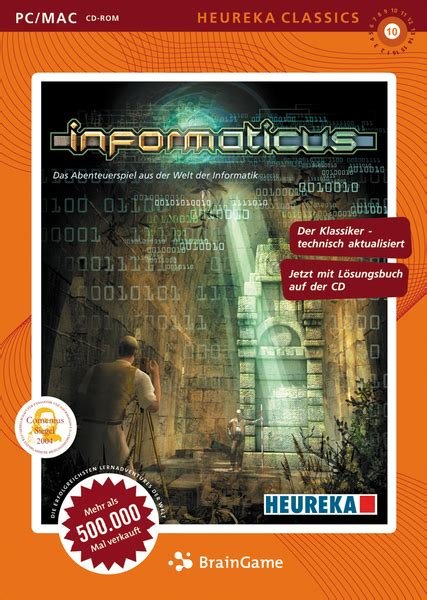

- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: HEUREKA-Klett Softwareverlag GmbH

- Developer: BrainGame Publishing, GmbH

- Genre: Adventure, Educational

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Puzzle elements

- Setting: Ancient civilization

- Average Score: 74/100

Description

Informaticus is an educational point-and-click adventure game set on a mysterious tropical island, where players, as the nephew of archaeologist Jacques Moreau, explore ancient temple ruins of a long-lost civilization that boasted advanced informational technology. Tasked with investigating enigmatic events plaguing the exploration team and the theft of two precious artifacts—a crystal orb and a golden cylinder—players solve intricate riddles and puzzles drawing from computer science, programming, logic, and cryptography, aided by a digital knowledge device filled with relevant educational content.

Gameplay Videos

Informaticus Free Download

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

adventure-archiv.com : A new learning adventure by Heureka-Klett is ‘Informaticus’, that deals with the concepts of data processing and computer science in an engaging archaeological mystery.

gog.com : This game has a really good story and plot, fun puzzles and teaches you a lot of the basics of IT! I would put it up there with the greatest of point-and-click adventures out there!

Informaticus: Review

Introduction

Imagine stumbling upon the ruins of an ancient civilization not known for its pyramids or coliseums, but for rudimentary computers, cryptographic codes, and algorithmic machines—thousands of years ahead of their time. This is the intriguing premise of Informaticus, a 2003 educational point-and-click adventure that blends archaeological mystery with computer science education. Released during the early 2000s edutainment boom, when games like The Oregon Trail were giving way to more sophisticated narrative-driven learning experiences, Informaticus stands as a bold experiment in merging puzzle-solving with informatics concepts. Developed by the German studio BrainGame Publishing GmbH in collaboration with bvm, and published by HEUREKA-Klett-Softwareverlag GmbH, it tasks players with unraveling a theft amid an expedition to a forgotten tropical island. As a game historian, I see Informaticus as a niche gem that anticipated the rise of “serious games,” though its punishing difficulty and language barrier have kept it from broader acclaim. My thesis: While its innovative fusion of detective intrigue and STEM education makes it a fascinating artifact of early-2000s edutainment, its overly demanding puzzles and dated mechanics limit its appeal, cementing it as a cult classic for logic enthusiasts rather than casual adventurers.

Development History & Context

Informaticus emerged from the Heureka Classics series, a line of educational adventures from HEUREKA-Klett, a publisher focused on interactive learning tools for schools and homes. Unlike in-house titles like Chemicus (2001), which explored chemistry through alchemy-themed puzzles, Informaticus was outsourced to Berlin’s bvm studio and Wiesbaden-based BrainGame Publishing GmbH, marking it as an external collaboration in the series. This shift allowed for a fresh take on informatics, a subject ripe for gamification amid the post-Y2K tech boom.

The project’s vision, spearheaded by scriptwriter and concept developer David Immanuel Richter (who also penned Chemicus), aimed to demystify computer science for young adults by embedding concepts like binary systems, cryptography, and programming into an archaeological narrative. Richter, alongside Sven Hermann (who handled both the educational content and programming), built the game around real informatics principles, ensuring puzzles weren’t just trivia but practical applications. Landscape design fell to Jan Schneider, while Pauline Kortmann crafted the visuals for the in-game knowledge database. The team used Macromedia Director as the engine, a multimedia authoring tool popular for CD-ROM era games, enabling pre-rendered scenes and QuickTime videos. This choice reflected the technological constraints of 2003: 500MB-1.1GB installations on dual CD-ROMs, hybrid compatibility for Windows and Mac (from PowerPC G3 400MHz with Mac OS 8.6), and no online features, as broadband was still nascent in Europe.

The gaming landscape at release was dominated by immersive adventures like Myst III: Exile (2001) and Syberia (2002), which emphasized atmospheric exploration and logic puzzles. Edutainment, however, was evolving from rote drills (Reader Rabbit) to narrative integration, with titles like Carmen Sandiego series teaching geography through chases. Informaticus fit this trend but targeted German-speaking audiences (exclusively in German, per sources), limiting global reach. Released on October 23, 2003, it carried a USK 0 rating (all ages) but a publisher recommendation of 12+, acknowledging its intellectual rigor. Development hurdles included manual installation (no auto-run due to copy protection) and sourcing music—curiously, much of the soundtrack was repurposed from Power Rangers Ninja Storm episodes and composer Johan van Barel’s works, adding an eclectic, sometimes mismatched tone. Budget constraints kept visuals photorealistic yet static, prioritizing educational depth over flashy effects.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Informaticus weaves a detective mystery around the lost civilization of the Baitaner (a phonetic nod to “byte”), an ancient people who worshipped Chaos and pioneered information technology millennia ago. The plot unfolds in four chapters, beginning with your arrival as Jacques Moreau’s unnamed nephew—a stand-in for the player—on a lush tropical island. Your uncle, the expedition leader voiced with gravitas by actor Meinke (evoking Patrick Stewart’s Captain Picard), briefs you: two artifacts, a crystal orb and a golden cylinder, have vanished from the team’s camp, amid whispers of sabotage. Armed with a “digital knowledge memory” (an in-game encyclopedia), you’re thrust into detective work, interrogating a nine-member team rife with jealousy, ambition, and hidden motives.

The narrative excels in character-driven intrigue. Jacques Moreau is the paternal mentor, dispensing wisdom and inventory items like a lighter (which he quips has “decades of adventurer tradition”). Teammates like the arrogant Taddeus Zech, the esoteric Erik Dennendahl, and the scheming Sara Fork form a web of interpersonal drama—envy over discoveries, romantic tensions, and ideological clashes mirror real expedition dynamics. Dialogue, fully voiced in German with subtitles, uses a “ping-pong” system: confront suspects with others’ statements to peel back layers, revealing backstories tied to the Baitaner’s lore. A pivotal vision in the Old Mill, triggered by a hallucinatory snake bite, unveils the Baitaners’ history: their Chaos religion, embodied by draconic statues and platonic elements on pentagonal slabs, parallels modern computing’s embrace of randomness (e.g., chaos theory in algorithms).

Thematically, Informaticus explores the intersection of ancient wisdom and modern tech, positing informatics as a timeless human endeavor. Puzzles aren’t mere obstacles but narrative extensions—decoding Baitaner scripts teaches cryptography’s evolution from hieroglyphs to HTTPS. The mystery culminates in the Chaos Temple, where you and Jacques set a trap for the traitor, blending whodunit tension with philosophical undertones on order vs. chaos. Subtle motifs, like the team’s digital vs. analog debates (echoed in monastery locations), underscore how technology amplifies human flaws. While the story resolves satisfyingly, its German exclusivity and dense exposition (relying on the knowledge base) demand investment, making it a cerebral thriller more than a page-turner.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Informaticus is a pure point-and-click adventure in first-person perspective, emphasizing exploration, dialogue, and logic puzzles over action. Navigation uses pre-rendered stills with cinematic camera angles and isometric views for puzzles, accessed via an expedition map for quick travel between sites like the Cenote or City in the Clouds. Mouse controls dominate: arrows for movement (forward, turn, zoom), a flashing cursor for hotspots (hand for manipulation, bulb for knowledge checks). The bottom interface pops up on hover, offering tabs for inventory, notebook (auto-logging tasks/events), and dialogues—though accidental clicks can frustrate.

Core loops revolve around three pillars: investigation, puzzle-solving, and learning. Dialogue is click-intensive, opening a full-screen window with tabs for characters (portraits and statements), objects, and locations (scrollable albums with descriptions and clues). Speak by holding the left mouse button and selecting the talk icon, then probing via notebook topics or cross-referencing quotes—95% yield rejections initially, building tension like a logic grid deduction game. Inventory management is straightforward but clunky: items (e.g., keys, rubbings) can’t be combined freely, and examining documents overlays the screen immovably, forcing manual note-taking for comparisons.

Puzzles, the game’s heart, draw from informatics: medium-to-hard difficulty, often nonlinear within chapters but gated sequentially. Early ones introduce Baitaner numerals (a decimal system), escalating to gate circuits, parity bits (using colored crystals in the City in the Clouds), Huffman coding (decoding a gong disc), Morse code redirection (frustratingly rhythm-sensitive, with no story hint—rely on context-sensitive knowledge base), quinary systems for water composition (building a crystal golem), and robot programming (navigating a mill labyrinth). Standouts include programming colored skull fountains in the Cenote (simulating logic gates) and timing spheres on a multi-level pinball track. The digital knowledge memory—accessible via menu or hotspots—provides tutorials on topics like L-systems or Conway’s Game of Life (for the Observatory finale), often interactively simulating solutions. Flaws abound: some puzzles feel arbitrary (e.g., musical codes in the Chaos Order), and repetition of code-breaking leads to fatigue. No combat or progression trees exist, but partial nonlinearity allows flexible ordering, with variable solutions (e.g., optional items). UI quirks, like poor hotspot visibility and non-resizable windows, highlight era limitations, yet the integration of education elevates it beyond rote edutainment.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The island of the Baitaner is a meticulously crafted tropical enigma, evoking Myst‘s isolation but infused with techno-mysticism. Locations are thematic microcosms: the tent camp as a modern hub; the Cenote’s cavernous depths with programmable skull-fountains and elevators; the pyramid-like Chaos Temple hiding organ-activated vaults; monasteries split between “digital” (rectangular, abacus-secured with Morse halls) and “analog” (circular, combinatorial locks); the botanical Chaos Order with draconic statues; the riverside Old Mill’s lochkarten mechanisms; the vertiginous City in the Clouds’ parity puzzles; and the nocturnal Observatory’s metallic globe. World-building shines through environmental storytelling—snakes block paths early, inscriptions reveal lore, and artifacts like the stolen orb symbolize lost knowledge. The Baitaners’ Chaos worship ties sites together, with platonic slabs representing elements (fire, water) as computational forces.

Art direction favors photorealistic 3D models sketched then rendered in Macromedia Director, yielding lush, static vistas: verdant jungles, weathered stones, and crystalline apparatuses. Character animations are sparse but charming, akin to Nancy Drew games—video cutscenes intersperse for key events, like the snake vision or trap-setting. Cross-fades between scenes toggle for performance, suiting mid-2000s hardware (Pentium III 450MHz min). Sound design is functional: ambient jungle noises and echoes enhance immersion, but the score—Jan Ullmann and Matthias Scheuer’s work, heavily recycled from Power Rangers Ninja Storm (e.g., Cenote tracks) and Johan van Barel’s ambient pieces—feels mismatched, swelling intrusively during puzzles. The knowledge base’s eerie tune matches Swamp Devil‘s tension. Voice acting, a Heureka hallmark, delivers spirited German performances, with subtitles aiding replay. Overall, these elements forge an atmospheric, educational sandbox where visuals and audio reinforce the theme of ancient tech in a primal setting, though emptiness in scenes can underwhelm exploration.

Reception & Legacy

Upon 2003 release, Informaticus garnered modest praise in German media, averaging 74% from sparse critics. Adventure-Treff lauded its “exquisitely beautiful” graphics, “well-implemented and attractive” interface, and “successful story for an edutainment title,” but docked points for “brutally tough” logic puzzles that overwhelmed non-experts, deeming it unsuitable for children despite the all-ages rating. Geo magazine hailed it as a “gripping decryption thriller” with mysterious happenings, while Wissen.de praised “snappy puzzles” embedded in a “captivating story” that vividly taught informatics basics. An English review from Adventure-Archiv (72%) echoed this: enthralling whodunit framed by frustrating, story-disconnected challenges, yet commended the comprehensive knowledge base for in-depth learning (e.g., cellular automata). No U.S. or English localization hurt commercial reach; sales data is scarce, but as a CD-ROM edutainment title, it likely targeted educational markets, spawning a 2004 official solution book by Jens Grabig.

Its legacy endures as a Heureka outlier—the only informatics entry in a series spanning chemistry (Chemicus), physics (Physicus), and history (Historion). It influenced niche edutainment by proving narrative could humanize abstract subjects, prefiguring games like The Talos Principle (2014) with philosophical puzzles or Return of the Obra Dinn (2018) in deduction mechanics. However, its German-only status and puzzle opacity confined it to cult status among adventure fans; sites like MobyGames and Backloggd note zero user ratings, while abandonware archives preserve it for emulation. In industry terms, it highlighted edutainment’s pitfalls—balancing fun and education—paving for modern titles like Kerbal Space Program. Today, it’s a historical curiosity, playable on vintage hardware or emulators, reminding us of gaming’s educational potential amid the rise of AI and coding literacy.

Conclusion

Informaticus is a ambitious artifact: a detective tale where ancient bytes unlock modern minds, blending compelling mystery, rich world-building, and informatics education into a cohesive if demanding package. Its strengths—immersive locations, witty dialogue, and a knowledge base that doubles as a textbook—outshine flaws like clunky UI, recycled audio, and overly opaque puzzles that alienate casual players. In video game history, it occupies a vital niche as a bridge between 1990s edutainment and sophisticated narrative games, influencing how we teach tech through play. For logic aficionados or German-speaking educators, it’s essential; for others, a challenging curiosity. Verdict: A commendable 7.5/10—innovative and intellectually rewarding, but best approached with patience and a walkthrough handy. Its place? A forgotten byte in the annals of educational adventures, deserving rediscovery in our algorithm-obsessed era.