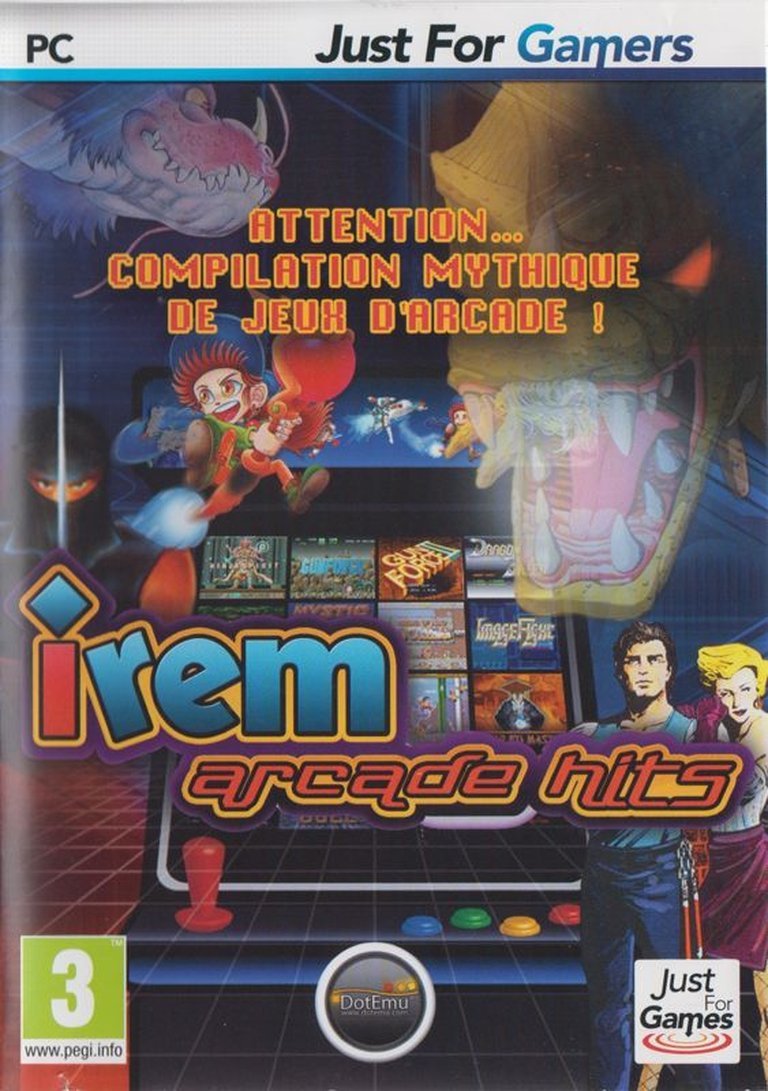

- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: DotEmu SAS, Just For Games SAS

- Developer: Irem Corp.

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

Description

Irem Arcade Hits is a compilation of eighteen classic arcade games originally developed by Irem, offering a diverse collection spanning genres like shoot ’em-ups, beat ’em-ups, platformers, and fighting games. Released in 2011 for Windows and Macintosh, it preserves iconic titles such as R-Type Leo, Kung-Fu Master, and GunForce, providing a nostalgic arcade experience for retro gaming fans.

Gameplay Videos

Irem Arcade Hits Free Download

Irem Arcade Hits Reviews & Reception

myabandonware.com : this bundle is good for what it is.

Irem Arcade Hits: A Monumental Compilation of Arcade Legacy

Introduction: The Arcade Time Capsule

In the pantheon of video game history, few studios embody the spirit of the arcade golden age quite like Irem. From the neon-lit cabinets of the 1980s to the digital storefronts of the 2010s, Irem’s catalog has been a cornerstone of genre innovation, blending intense action with unforgettable visuals. Enter Irem Arcade Hits, a 2011 compilation that distills two decades of arcade mastery into a single, DRM-free package for Windows and Mac. Released during a renaissance of retro re-releases, this collection is not merely a nostalgia trip but a critical archival effort, preserving eighteen seminal titles that defined—and in many cases, reinvented—their respective genres. My thesis is clear: Irem Arcade Hits stands as an indispensable historical document, offering a raw, unfiltered glimpse into Irem’s creative zenith, even as its technical execution and curation reveal the challenges of translating arcade perfection to the digital age. Through exhaustive analysis, this review will argue that the compilation’s true value lies in its role as a time capsule, capturing the audacious vision of a studio that balanced technological constraints with unparalleled creativity.

Development History & Context: From Arcade Cabinets to Digital Storefronts

The Irem Phenomenon: A Studio Forged in Arcade Fire

Irem, originally known as IPM, emerged in the late 1970s as a Japanese manufacturer of arcade hardware and games. The studio’s early forays, such as Moon Patrol (1982) and 10-Yard Fight (1983), showcased a knack for genre hybridization, but it was the mid-1980s that saw Irem ascend to legend status. Under the leadership of designers like Takashi Nishiyama (who would later create Street Fighter at Capcom), Irem pioneered mechanics that would ripple through the industry. The arcade era was defined by technological constraints—custom PCBs like the M72 and M92 boards limited memory and processing power—yet Irem turned these limitations into stylistic strengths. Sprites were bulky but expressive, scrolling was often parallax or single-axis, and soundtracks leaned on chiptune grandeur. The gaming landscape of the time was a chaotic, competitive arena where a single hit could fund a studio for years; Irem’s output from 1984 to 1994, spanning Kung-Fu Master (1984) to GunForce II (1994), reflects a period of relentless experimentation.

The 2011 Compilation: DotEmu’s Preservation Mission

By 2011, the arcade compilation had become a staple of digital distribution, with series like Namco Museum setting benchmarks. Irem Arcade Hits was developed by Irem Corp. but ported and packaged by DotEmu SAS, a French studio renowned for its emulation expertise (notably on projects like R-Type Dimensions). Released on June 1, 2011, for Windows and Macintosh, the collection was published by Just For Games SAS and DotEmu SAS, with a PEGI 3 rating indicating family-friendly accessibility—a curious choice given the violent themes of games like Vigilante and Undercover Cops. The business model was commercial, sold via CD-ROM and download, but today it languishes as abandonware, freely available on sites like My Abandonware and the Internet Archive. This shift underscores the compilation’s dual nature: a commercial product and a grassroots preservation tool. DotEmu’s involvement, credited to programmers Mickaël Savafi and Romain Tisserand, ensured faithful emulation, though user reports of DLL errors on modern Windows systems reveal the fragility of such preservation efforts.

Technical Constraints and Emulation Challenges

The original arcade hardware varied wildly—from the M62 board powering Kung-Fu Master to the M92 for GunForce—each with unique memory mappings and processors. DotEmu’s task was to replicate these environments on x86 PCs, a feat they accomplished with varying success. The compilation supports gamepads, keyboards, and mice, but purists will notice input lag or mapping issues, especially in precision-oriented titles like Ninja Spirit. The 69 MB download size suggests efficient ROM dumps, yet the reliance on system DLLs (as noted by a My Abandonware user) highlights how software rot can undermine even the best-preserved classics. In this context, Irem Arcade Hits is both a triumph and a warning: it brings these games to new audiences but depends on emulation layers that may not age gracefully.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Heroes, Havoc, and the Human Condition

Unlike a modern narrative-driven game, Irem Arcade Hits is a mosaic of discrete stories, each reflecting the archetypal arcs of 80s/90s arcade design. Yet, threading through all eighteen titles are recurring themes of heroism, sacrifice, and the fight against overwhelming odds—a testament to Irem’s creative through-line.

The Martial Arts Ethos: From Kung-Fu Master to Ninja Spirit

Kung-Fu Master (1984), based on the film Game of Death, casts players as Thomas, a martial artist storming a pagoda to rescue his kidnapped girlfriend. Its narrative is minimal but iconic: five floors of progressively tougher enemies, culminating in a boss fight. This “rescue mission” trope would echo in Hammerin’ Harry (1990), where the titular carpenter battles construction corruption to save his town, blending blue-collar humor with platforming heroics. Ninja Spirit (1988) offers a more somber tale: two ninja clans at war, with players seeking vengeance for a fallen master. The game’s atmospheric levels—burning temples, misty forests—imbue a sense of tragic lore despite sparse dialogue. These titles exemplify Irem’s fascination with Eastern motifs, albeit filtered through a Westernized arcade lens where action trumps exposition.

Sci-Fi and the Cosmos: R-Type Leo and ImageFight

Irem’s sci-fi output is arguably its most influential. R-Type Leo (1992), a spin-off of the flagship R-Type series, ditches the iconic Bydo Empire for a more abstract threat: a rogue AI controlling a space station. The narrative is conveyed through brief cutscenes and environmental storytelling—glowing cores, mechanical monstrosities—emphasizing isolation and technological dread. ImageFight (1988) similarly merges human pilots with transformable mechs to combat an alien invasion, its plot reduced to mission briefings that prioritize gameplay over depth. Yet, the themes are consistent: humanity versus mechanistic annihilation, a reflection of Cold War anxieties permeating 80s game design. Dragon Breed (1989) and Cosmic Cop (1991) extend this, with the former featuring dragon-riding knights in a fantasy-sci-fi blend, and the latter pit police in mech-suits against interstellar criminals—each using setting to justify relentless shooter action.

Street-Level Conflict: Vigilante, Undercover Cops, and Blade Master

For ground-based combat, Irem excelled at urban grit. Vigilante (1988), licensed to Data East, is a beat ’em up where a biker gang defends a neighborhood from thugs, its narrative a series of punchy interstitials about “cleaning up the streets.” Undercover Cops (1992) ups the ante with co-op play, casting players as rogue cops taking down a drug syndicate; its cutscenes ooze 90s excess, with explosions and one-liners underscoring a “loose cannon” trope. Blade Master (1991) merges fantasy with beat ’em up, as warriors battle demonic forces in a dark realm—its lore hinted through enemy designs and item descriptions. These games share a thematic core: the lone (or duo) hero against institutional corruption or supernatural evil, a cathartic fantasy for arcade-goers seeking empowerment.

The Anomalies: Superior Soldiers and GunForce

Superior Soldiers (1993) is Irem’s lone foray into versus fighting, with a no-story approach focused on roster diversity—cyborgs, mutants, and warriors in a tournament setting. Its theme is pure spectacle, lacking the narrative cohesion of other titles. Conversely, GunForce (1991) and GunForce II (1994) are run-and-gun epics with轻度 storytelling: soldiers battling a terrorist organization across war-torn landscapes. The sequel’s subtitle, “Battle Fire Engulfed Terror Island,” signals a B-movie sensibility, where plot exists merely to frame explosive set-pieces.

Synthesis: Irem’s Thematic Signature

Across the compilation, narratives are skeletal but potent, serving as scaffolding for gameplay. Common threads include:

– Sacrifice and Duty: Heroes are often motivated by loss or obligation (e.g., Kung-Fu Master’s rescue, R-Type Leo’s last-stand against AI).

– Man vs. Machine: From ImageFight’s mechs to R-Type’s Bydo, technology is both tool and threat.

– Cultural Fusion: Japanese settings mingle with Western archetypes—ninjas next to biker gangs—reflecting a globalized arcade market.

– Redemption Arcs: Even in games like Hammerin’ Harry, where the hero is a cheerful everyman, the underlying theme is restoring justice.

These narratives, while simplistic by modern standards, are高效 in establishing stakes and tone, a hallmark of arcade design where gameplay clarity is paramount. Irem Arcade Hits collects these stories not as novels but as vignettes, each a pixelated echo of the hero’s journey.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Genre Kaleidoscope

The compilation’s genius—and its greatest challenge—lies in its diversity. Eighteen games span shoot ’em ups, beat ’em ups, platformers, run-and-gun, and fighting, each with distinct mechanics that defined genres but also reveal Irem’s iterative evolution.

Shoot ’Em Ups: Bullet Hell Before Bullet Hell

Irem’s shooters are its crown jewels, blending precision with chaos. Titles like Air Duel (1990), Battle Chopper (1987, aka Mr. Heli no Daibōken), Cosmic Cop (1991), Dragon Breed (1989), ImageFight (1988), In the Hunt (1993), Mystic Riders (1992), R-Type Leo (1992), and Ninja Spirit (1988, a platformer-shooter hybrid) showcase different approaches.

– Core Loops: Most employ vertical or horizontal scrolling, with power-ups (speed, weapons, shields) collected from defeated enemies. R-Type Leo innovates with a customizable “Force” pod that can be detached for independent fire—a mechanic that would influence later shooters. ImageFight features transformable ships that shift between air and ground modes, adding layer-based strategy.

– Innovations: Dragon Breed introduces dragon-riding, where the mount has its own health, creating a dual-resource management. In the Hunt (1993) is a submersible shooter, using pressure gauges and oxygen management to heighten tension—a rare aquatic focus.

– Flaws: Many suffer from “arcade fairness”: cheap enemy spawns, hitbox obscurity, and relentless bullet patterns. Ninja Spirit’s platforming segments can feel clumsy next to pure shooters. The compilation’s emulation sometimes exacerbates input lag, crucial for frame-perfect dodges.

Beat ’Em Ups and Run-and-Gun: Co-op and Carnage

Blade Master (1991), Kung-Fu Master (1984), Undercover Cops (1992), Vigilante (1988), GunForce (1991), and GunForce II (1994) represent side-scrolling melee and shooting hybrids.

– Core Loops: Kung-Fu Master established the template: punch-kick combos, jumping attacks, and boss arenas. It introduced a health bar that depletes on hit but regenerates slowly—a novel mechanic then, now a staple. Vigilante and Undercover Cops expand this with more moves and environmental interactions (e.g., picking up weapons). GunForce shifts to run-and-gun, with vehicle sections and dual-wielding, emphasizing mobility over static brawling.

– Innovations: Undercover Cops allowed two-player co-op with character-specific moves (one a brawler, one a shooter), a depth rare in early 90s beat ’em ups. GunForce II added more elaborate stage hazards and a “super move” system.

– Flaws: These games can be punishingly difficult, with “cornering” by enemies and sparse health pickups. Blade Master’s fantasy setting is engaging but its combat feels weightless compared to Kung-Fu Master’s crisp hits.

Platformers and Miscellaneous: Precision and Quirk

Hammerin’ Harry (1990), Legend of Hero Tonma (1989), and Ninja Spirit (1988) blend platforming with action.

– Hammerin’ Harry is a construction-themed platformer where Harry wields a giant hammer to smash obstacles and enemies, with precise jumping and hidden paths. Its charm lies in whimsical visuals and slow-building challenge.

– Legend of Hero Tonma is a surreal, puzzle-like platformer with a hero who can throw his hat like a boomerang, emphasizing exploration over combat.

– Superior Soldiers (1993) is a versus fighter with a unique “super meter” system, but it lacks the depth of contemporaries like Street Fighter II.

Systems Overview: Emulation and User Experience

DotEmu’s emulation layer handles the hardware abstraction, but the compilation lacks modern amenities: no save states, no rewind, minimal configuration options. The input system is customizable but not always responsive. This purity—warts and all—will please purists but frustrate casual players. The inclusion of 1-2 player offline modes preserves arcade camaraderie, yet the absence of online multiplayer or leaderboards feels dated even for 2011.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Pixelated Perfection

Irem’s arcade output was defined by a distinct aesthetic that married technical savvy with artistic flair, and Irem Arcade Hits preserves these visuals and audio with nostalgic fidelity.

Visual Direction: From Sprites to Scrolling

Irem’s artists worked within tight sprite limits (often 16×16 or 32×32 pixels) but achieved remarkable expressiveness. Kung-Fu Master’s characters are bulky yet animated with fluid punches and kicks; R-Type Leo’s ships are detailed, with Gear-like forces that animate when detached. Backgrounds use parallax scrolling sparingly—ImageFight’s alien landscapes shift layers to create depth—while titles like Dragon Breed employ foreground obstacles to enhance 3D illusion. Color palettes are vibrant but limited, with Irem favoring earthy tones for fantasy games (Blade Master) and neon blues/reds for sci-fi (R-Type series). The compilation’s emulation captures these details, though on modern displays, scanlines and aspect ratios may need tweaking via third-party shaders.

Sound Design: Chiptune Grandeur

Irem’s soundtracks, composed by M.T.O. (Masato Ishizaki) and others, are synth-driven masterpieces. R-Type’s main theme is iconic, but even lesser-known titles shine: In the Hunt uses dissonant, aquatic tones for underwater tension; Hammerin’ Harry has jaunty, folk-inspired tunes. Sound effects are punchy—explosions, laser blasts, character grunts—with a tactile quality that emphasizes impact. The compilation’s audio emulation is generally accurate, though some users report slight timing drifts, a common issue in software emulation.

Atmosphere and Cohesion

What’s striking is how each game world feels distinct despite shared hardware constraints. Vigilante’s urban decay contrasts with Mystic Riders’ mythical realms; Undercover Cops’ gritty streets versus Legend of Hero Tonma’s dreamlike platforms. This variety is a strength, showcasing Irem’s versatility. However, the compilation offers no context—no developer commentary, no art galleries—which feels like a missed opportunity for deeper appreciation. The worlds exist in isolation, a byproduct of the arcade era’s focus on immediate engagement over lore.

Reception & Legacy: Niche Praise, Lasting Influence

Critical and Commercial Reception at Launch

Irem Arcade Hits arrived with little fanfare. Unlike Namco’s polished Museum series, it received scant media coverage. IGN’s summary page lists the games but offers no review; Metacritic shows no critic or user reviews (as of source data), and MobyGames records only one user rating of 4.0/5. Commercial success was muted—DotEmu’s shop later closed, and the compilation faded into abandonware. Critics of the era might have dismissed it as “shovelware” (as My Abandonware tags it), lacking the curation of Namco Museum or Capcom Classics. Yet, among retro enthusiasts, it gained quiet acclaim for its comprehensive lineup and DRM-free policy.

Evolution of Reputation: A Cult Classic Emerges

Over time, Irem Arcade Hits has been re-evaluated as a preservation milestone. With Irem’s shift toward console RPGs (e.g., Disaster Report) and the decline of arcade development, this compilation became one of the few official PC releases of Irem’s arcade library. The GOG Dreamlist entry from user @isluji94 (2025) encapsulates this: “It contains a lot of classic arcade games, and in default of a PC release of IREM Collection modern console volumes, it would be nice if this is rescued from oblivion.” This sentiment highlights its importance in an era where Irem’s arcade classics are sporadically re-released (e.g., Irem Arcade 1 on Evercade in 2022, Irem Collection on modern consoles in 2023). Compilations like Irem Arcade Classics (1996) predated it, but Irem Arcade Hits offered updated emulation and broader accessibility.

Influence on the Industry and Retro Gaming

While not groundbreaking in design, the compilation reinforced the value of archival efforts. It joined a wave of 2010s compilations (e.g., Gunlord, Mega Man Legacy), advocating for classic games on digital platforms. Its shortcomings—no enhancements, basic emulation—sparked discussions about best practices for re-releases, influencing later projects that add save states, filters, or historical notes. For Irem specifically, it kept the arcade catalog alive during a dormancy period, feeding demand that culminated in the more robust Irem Collection.

Preservation Challenges

User reports on My Abandonware—DLL errors, compatibility issues—expose the fragility of digital preservation. Unlike physical cartridges or boards, digital compilations rely on aging emulators and system libraries. The Internet Archive’s hosting ensures access but not playability without tinkering. This duality—widely available yet technically temperamental—makes Irem Arcade Hits a case study in the ephemeral nature of retro gaming media.

Conclusion: An Imperfect Time Capsule, But an Essential One

Irem Arcade Hits is not without flaws: the emulation is serviceable but not flawless, the presentation is barebones, and the curation, while broad, lacks contextual depth. Yet, to dismiss it is to overlook its monumental role in preserving Irem’s arcade legacy. These eighteen games represent a studio at its most innovative—Kung-Fu Master birthing the beat ’em up, R-Type defining shooters for decades, Undercover Cops pushing co-op boundaries. The compilation’s narratives, though simple, pulse with the earnest heroism of arcade design; its mechanics, varied and often challenging, showcase Irem’s genre-spanning prowess; its aesthetics, pixelated yet vivid, capture a bygone era of technical artistry.

In video game history, Irem Arcade Hits occupies a unique niche: it is a commercial release that functioned as an act of preservation, bridging the physical arcade and the digital future. Its legacy is twofold—providing immediate access to classics and highlighting the need for more thoughtful re-releases. For historians and players alike, it remains a vital, if rough-around-the-edges, portal to Irem’s golden age. As long as the DLLs can be fixed and the emulation tweaked, this compilation will endure as a monument to the audacity of arcade game design. Final verdict: Highly recommended for retro enthusiasts and scholars, with caveats about technical setup. It is not the definitive way to experience these games—dedicated emulators or modern compilations may offer smoother playback—but as a snapshot of Irem’s output, it is unparalleled. In the grand archive of gaming, Irem Arcade Hits is a dusty, invaluable ledger, waiting to be dusted off and played.