- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Android, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: magnussoft Deutschland GmbH, Runesoft GmbH

- Developer: magnussoft Deutschland GmbH

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Collection, Platform, Power-ups

Description

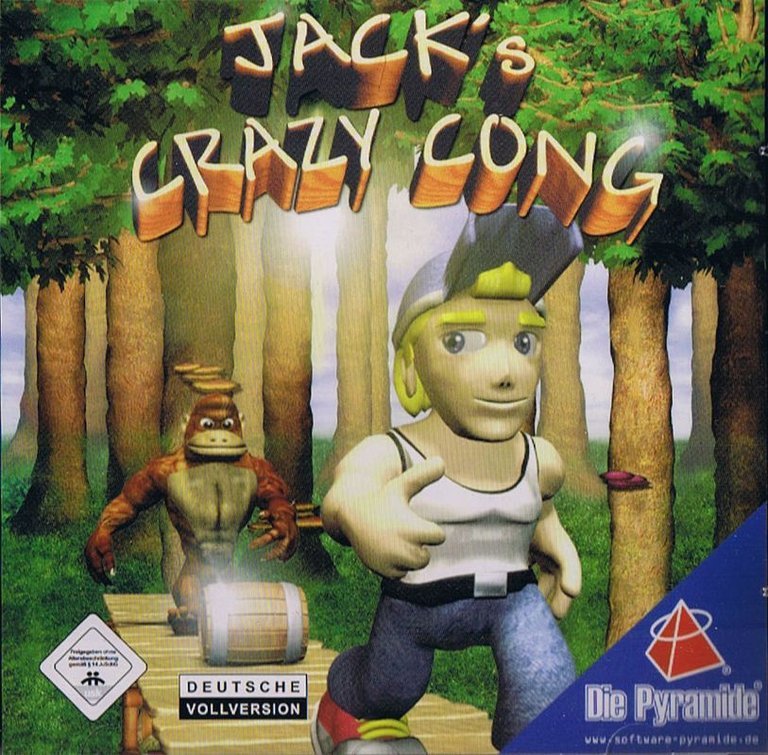

Jack’s Crazy Cong is a traditional 2D side-scrolling platformer featuring over 30 levels where players control Jack as he collects bananas to confront Cong the ape. Suitable for younger children, the game involves evading hazards like barrels, fire, and bees thrown by Cong, using power-ups to overcome obstacles, and includes three bonus retro games on the CD.

Jack’s Crazy Cong: A Forgotten Artifact of the European Casual Platformer Boom

Introduction: The Banana in the Room

In the vast, crowded archives of video game history, certain titles shimmer with the polish of critical darlings or industrial blockbusters, while others exist in the quiet, dimly lit corners—games known primarily to dedicated archivists, regional players, and the developers who shepherded them. Jack’s Crazy Cong is one such title. Released in November 2005 by the German studio magnussoft Deutschland GmbH, this 2D side-scrolling platformer represents a specific, often-overlooked strand of early-2000s game development: the earnest, mechanically straightforward, youth-oriented “jump-and-run” designed for the budget-conscious PC market and its family-friendly software aisles. This review posits that Jack’s Crazy Cong is not merely a footnote but a crucial diagnostic tool for understanding a period of transition. It sits at the intersection of the retro-platformer revival and the dawn of the casual digital distribution era, embodying both the charming simplicity and the fundamental limitations of its genre and economic moment. Its legacy is not one of innovation, but of endurance—a testament to the viability of low-cost, content-rich games built on familiar foundations.

Development History & Context: The Magnussoft Model

The Studio and Its Ethos: magnussoft Deutschland GmbH was, and remains, a quintessential European “budget” and “budget-adjacent” publisher/developer. Operating from Germany, the company carved out a niche by producing a high volume of accessible games, often for the Windows PC market, which retained significant retail presence in Europe through the 2000s. Their business model relied on low development costs, modest sales expectations, and frequent bundling. The Jack series—including Jack’s Attic (1996) and Jack’s Sokoman (2004)—was one of their flagship in-house properties, a named franchise used to build brand recognition among a family audience.

Technological Constraints and Aesthetic Choices: The game’s technical specs reveal its era. A 2005 Windows release with a USK rating of 0 (suitable for all ages), distributed on CD-ROM, it was squarely aimed at non-gaming PCs and pre-teens. The “2D scrolling” perspective and “Direct control” interface were not stylistic choices born of artistic vision but of practical necessity and market targeting. Developing a full 3D game would have been economically unfeasible for a project of this scope. The pixel-art style, executed by graphics artist Sascha Feyrer, would have been created using accessible tools of the time, prioritizing clear, readable sprites over graphical fidelity. The decision to support keyboard, mouse, and joystick speaks to a desire for maximum accessibility across the disparate hardware configurations of the average family computer.

The Gaming Landscape of 2005: The platformer was in a fascinating state. The 3D boom of the late 90s had seemingly made 2D a relic, yet a strong counter-movement was brewing. Games like Knytt (later), The Behemoth’s Alien Hominid (2004), and the retro-RPG revival signaled a hunger for simpler, skill-based experiences. However, the mainstream “casual” space was beginning to be defined by puzzle games (Bejeweled) and simple browser titles. Jack’s Crazy Cong did not arrive as a hip retro-nostalgia piece; it arrived as a continuation of a tradition. It was a functional, unpretentious entry in a genre that still had a massive, underserved audience of young children and casual players who found 3D navigation confusing. Its existence is proof that the 2D platformer, far from dead, was quietly thriving in the discount bins and children’s sections of European software stores.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Banality as a Design Philosophy

The game’s “plot,” as extracted from its description, is an exercise in minimalist storytelling: “The player takes on the role of Jack, whose task is to smooth down Cong, the ape, and to do that he must collect all of the bananas.” This is not a narrative; it is a gameplay directive. The antagonist, Cong, is not a character but an archetype—the “ape” from Donkey Kong, recontextualized. His methods (“throws things like barrels or sends fire or bees”) are lifted directly from the 1981 Nintendo classic, establishing Jack’s Crazy Cong not as an original intellectual property but as an explicit homage and variant.

There is no dialogue, no lore, no emotional motivation. “Smooth down Cong” is a delightful euphemism for defeat, implying a non-violent, almost playful resolution. The theme is pure, unadulterated play. The world is a jungle obstacle course where the only meaningful interaction is between Jack’s movement and Cong’s projectiles. The bananas are MacGuffins of the purest kind—their collection is the sole metric of progression. This narrative vacuum is, in fact, the game’s primary thematic statement: for its target audience (younger kids), the story is irrelevant. The experience is the jumping, the dodging, the collecting. The thematic depth is found in this honest, unadorned focus on core gameplay loops, a philosophy that contrasts sharply with the narrative-heavy, cinematic aspirations of many of its 2005 contemporaries. It is a game that understands its purpose: to be played, not to beread or watched.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The DNA of Donkey Kong, Replicated

Core Loop: The loop is instantly recognizable to anyone familiar with the genre. Navigate a side-scrolling level from a left-side start to a right-side goal, avoiding static and moving hazards, with the mandatory secondary objective of collecting all scattered bananas. Completing a level unlocks the next. This is platforming 101, executed with reliability.

Combat & Hazards: Jack does not “fight” in a traditional sense. The description states he can use “power-ups” to “fight against these things.” This suggests a simple projectile or temporary invincibility mechanic, likely a single-use item found in the level (an echo of Super Mario Bros.‘ fire flower). The primary interaction is avoidance and navigation. Hazards are Cong’s direct attacks: barrels (rolling, predictable trajectories), fire (static or patterned), and bees (flying, potentially homing). This creates a gameplay rhythm of observation, timing, and execution—the foundational skills of the platformer.

Progression & Structure: “More than 30 levels” with the possibility of user-downloadable additions points to a level-based, discrete challenge structure. There is no mention of a metroidvania-style ability-gated exploration or RPG statistics. Progression is likely linear, with new levels introducing slight variations on the hazard set—more barrels, faster bees, complex fire patterns. The difficulty curve would be steep for a young child but forgiving by hardcore platformer standards, relying on repetition and pattern memorization.

Interface & Controls: The support for keyboard, mouse, and joystick is significant. It indicates a design not for precision gaming rigs but for whatever input device was handy. Mouse support might imply point-and-click movement or menu navigation, a common but often-clunky solution in casual PC games of the era. The “Direct control” tag suggests 1:1 input-response, avoiding momentum-based physics (like Super Mario 64‘s initial movement) in favor of immediate, predictable character response—critical for younger players.

Innovation vs. Flaw: Innovation is not the game’s goal. Its strength is clarity and completeness. The “flaw” is inherent to its model: without the budget for bespoke mechanics, lavish animation, or intricate level design puzzles, it risks feeling sterile or repetitive. The potential for depth lies in the level design’s quality and the interplay of hazards, but with over 30 levels, there is a high probability of padding or recycled layouts. The inclusion of three other full retro games (Crazy Quader, Z. Zapper, Holiday Puzzle) on the same CD is a magnussoft hallmark—a value-add that acknowledges the game itself may not command a full price on its merits alone. This bundling is a business strategy, not a feature, but it profoundly shapes the user’s relationship with the product: Jack’s Crazy Cong is the flagship, but the other games are the insurance policy against buyer’s remorse.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Functional Evocation

Visual Direction & Atmosphere: The “jungle” setting is a generic, brightly colored backdrop. Based on the era and the “traditional” descriptor, the art style is likely colorful, with high-contrast sprites against detailed (but simple) parallax scrolling backgrounds. The atmosphere is cheerful and non-threatening. There is no darkness, no oppressive beauty—just a play-space. The visual language prioritizes readability: hazards must be immediately identifiable, platforms distinct from background, and collectibles (bananas) pop. This is functional art, where aesthetic is subordinate to gameplay communication.

Sound Design & Music: Composed by Marcin Wilga (credited as “Aumeso” on the Moby page, a likely pseudonym or production credit), the soundtrack would fit the “casual platformer” genre: upbeat, looping, melodic tunes in a major key, perhaps with a light tribal or Caribbean percussion flavor to match the jungle theme. Sound effects would be sparse but distinct: a “ploop” for collecting a banana, a “bonk” for hitting a hazard, a comical “ooh-ooh-ah-ah” for Cong’s appearances. The goal is audial reinforcement of actions, not atmospheric immersion. The soundscape is a tool for feedback, not for mood.

Synthesis: The cumulative effect is one of competent, cheerful functionality. The world does not transport the player; it presents them with a clean, colorful, predictable challenge board. It is the digital equivalent of a well-designed playground: functionally engaging, brightly colored, and utterly without mystery or depth. This is not a critique of failure, but an analysis of intent. For a child learning coordination and pattern recognition, this is the ideal environment.

Reception & Legacy: The Silence of the Budget Bin

Critical & Commercial Reception (At Launch): There is a profound silence. Metacritic lists “Critic reviews are not available,” and the MobyGames player review section is empty. This is the hallmark of a deeply niche, retail-only, non-marquee title. It would have received minimal to no coverage from mainstream outlets, which in 2005 were focused on AAA console releases and emerging PC phenomena like World of Warcraft. Its commercial success was measured in units sold through European PC software retailers like PC-Ware or smaller department store computer sections. The lack of records suggests sales were modest but sufficient to justify sequels—a key indicator of the budget model’s health.

Evolution of Reputation: The game’s reputation has not evolved because it scarcely existed in the critical consciousness to begin with. Within retro gaming and preservation circles, it is known as a “Donkey Kong variant” (its primary MobyGames group) and a piece of the magnussoft puzzle. Its value today is historical and archival, not cultural. It is a data point for researchers studying:

1. The continued viability of 2D platformers in the mid-2000s.

2. The German/European budget game market.

3. The lifecycle of a minor franchise (note the immediate sequel, Jack’s Crazy Cong 2, released the same year).

4. The packaging of value through multiple game compilations on a single CD.

Influence on the Industry: Jack’s Crazy Cong exerted zero direct influence on major industry trends. It did not inspire indie developers or lead to new genres. Its influence is structural and economic: it represents the “long-tail” commercial model that allowed small European studios to survive by producing steady, low-risk content for a specific demographic. The game’s most significant legacy may be indirect: its existence, and that of its many sequels (Jack’s Crazy Cong 2, Jack’s Crazy Special), proves there was a sustainable, if quiet, market for exactly this kind of game for over a decade. It is a cousin, not a parent, to the later indie platformer boom—sharing the same genetic code (2D, simple controls, cheerful aesthetic) but born of a different economic ecosystem (retail discount vs. digital storefronts).

Conclusion: Verdict and Historical Position

Jack’s Crazy Cong is not a game to be judged by the standards of “classic” or “seminal.” It is a competent artifact. It succeeds at its apparent goals: it delivers a substantial number of levels (30+), uses clear and functional graphics, implements intuitive controls, and provides a difficulty curve appropriate for its young target audience. It fails, or rather, it does not attempt, to achieve any aspirations of artistry, narrative depth, mechanical innovation, or lasting emotional impact.

Its place in video game history is that of a canary in the coal mine of the casual platformer’s quiet persistence. While the industry’s gaze was fixed on 3D open worlds and online multiplayer, games like Jack’s Crazy Cong were guaranteeing that the core act of jumping over a pit to collect a fruit remained alive and well in the households of non-gamer parents who bought a cheap CD at the supermarket. It is a reminder that the ecosystem of game development is far broader than the headline-grabbing titles, and that centuries of design knowledge—from Donkey Kong to Super Mario Bros.—were being packaged, refined, and sold to new generations through unassuming, profoundly traditional vehicles like this one.

Final Score: 6/10

(A functional, painless, and entirely disposable experience that perfectly fulfills its modest design brief without ambition or distinction. Its worth is not in playing it today, but in recognizing it as a specimen of a bygone, pragmatic era of game development.)