- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Publisher: Levande Böcker i Norden AB

- Developer: Dorling Kindersley

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Word construction

Description

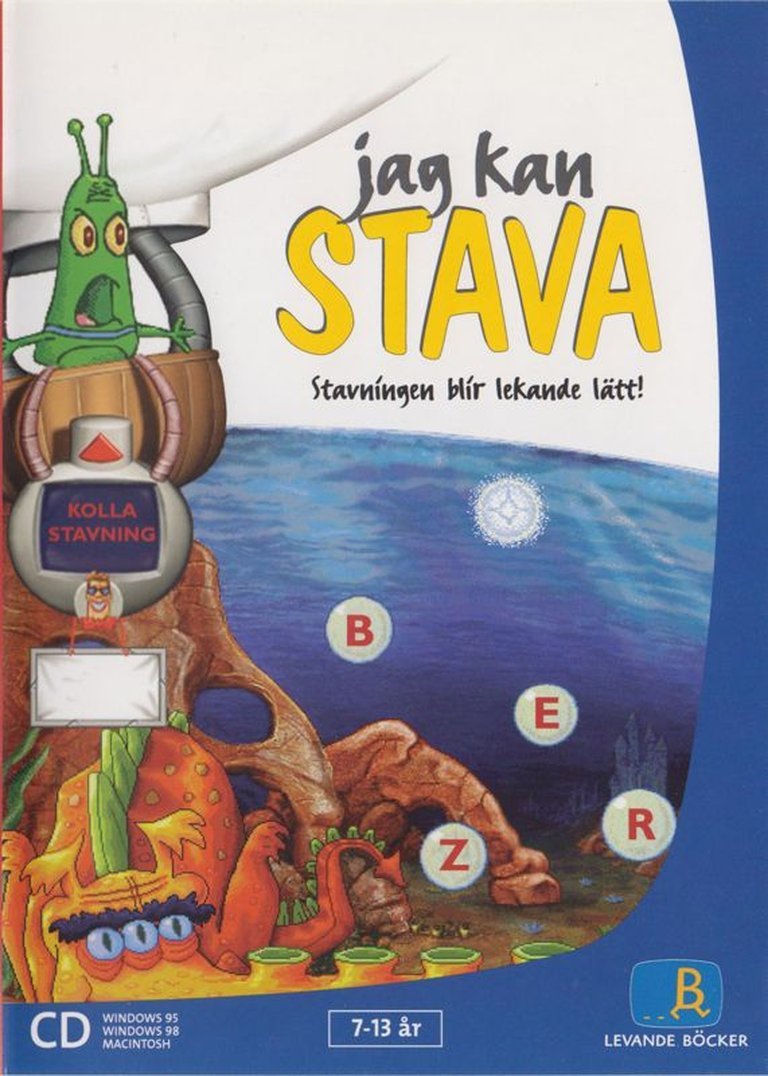

Jag kan stava is a Swedish educational game designed for children aged 7 to 13, focusing on teaching spelling and language fundamentals. Developed by Dorling Kindersley in collaboration with child language learning experts, the program features approximately 4,000 words across six different games with three difficulty settings, covering letters, sounds, spelling rules, word classes, roots, prefixes, and suffixes. It supports single-player and competitive two-player modes, aiming to make spelling practice engaging through various activities like word construction and visual recognition.

Jag kan stava Free Download

Jag kan stava: A Zeitgeist in Swedish Spelling Pedagogy

Introduction: More Than a Spelling Drill

In the crowded pantheon of 1990s educational software—a genre often dismissed as digitized flashcards—Jag kan stava (translated: “I can spell”) emerges not as a revolutionary paragon, but as a meticulously crafted, culturally-grounded artifact of its time. Released in 1998 for Windows and Macintosh by publishers Levande Böcker i Norden AB (Living Books in the Nordic Region) and developers Dorling Kindersley, this Swedish-language title represents a critical juncture where serious pedagogical intent met the burgeoning potential of the CD-ROM. Its legacy is not one of global sales charts, but of quiet, effective integration into the Swedish classroom and home, leveraging beloved literary characters to transform the often-grueling process of spelling acquisition into an interactive narrative adventure. This review posits that Jag kan stava’s true significance lies in its demonstration of how educational games could achieve a harmonious, if technically modest, fusion of curriculum-aligned learning objectives, charming local color, and engaging game-like structures—a model that, while eclipsed by technological leaps, remains a benchmark for culturally-specific edutainment.

Development History & Context: Bridging Books and Bytes

The Studio and Its Mission: The development credits paint a picture of transatlantic collaboration. Dorling Kindersley (DK), the iconic British publisher known for its visually rich, informational “Eyewitness” books, was licensing its brand and design philosophy to software. However, the Swedish publisher Levande Böcker i Norden AB, a key regional player in children’s media, was the driving force, ensuring deep cultural and linguistic relevance. The game is part of the “Krakels ABC” series, based on characters from the classic Swedish children’s book series by Lennart Hellsing and Poul Ströyer—most notably the eccentric cousin figure, Kusin Vitamin. This literary lineage was not a mere coat of paint; it provided a pre-existing universe, character archetypes, and visual style that Swedish children would recognize, lending the game instant familiarity and trust.

Technological Constraints and Aesthetic Choices: The late 1990s CD-ROM era was a golden age for multimedia educational titles. Constraints were significant: the “fixed/flip-screen” perspective mentioned in the MobyGames specs meant pre-rendered static backgrounds with clickable hotspots, a common technique to conserve memory for voice acting and animation. The choice of a first-person perspective, as noted in the specs, is intriguing. It suggests an immersive “you are there” approach, pulling the child directly into the world of Näppelunda, rather than observing a protagonist. This was likely a deliberate design to foster agency, a key motivational factor in learning. The presence of fully voiced dialogue in Swedish—a notable production cost—was a major differentiator from text-only predecessors and a clear signal of quality aimed at both children and educators.

The Gaming and Educational Landscape: In 1998, the educational market was dominated by giants like The Oregon Trail and Reader Rabbit in the West. Jag kan stava entered a space where the debate was shifting from “if” games could teach to “how” they could teach most effectively. Its release coincided with growing academic interest in multimedia learning theories. By developing activities “in cooperation with experts on language learning for children,” as the MobyGames description states, the title positioned itself not as a casual game with educational veneer, but as a serious pedagogical tool, a claim supported by its structured curriculum covering “letters and sounds, spelling rules and exemptions, word-classes and roots.”

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The World of Näppelunda

While the MobyGames entry provides the skeletal framework—a spelling game for ages 7-13—the GameArchives source fleshes out the narrative skeleton with invaluable detail. The game is not an abstract series of drills; it is a place: the fictional Swedish town of Näppelunda, specifically its waterfront. This setting is not arbitrary. The waterfront, with its warehouses, radio stations, and prisons, provides a logical, thematic backdrop for the three core mini-games, each a clever metaphor for the spelling challenges they present.

1. The Shipping Warehouse (Container Labels): Players encounter containers with missing label letters. The puzzle is to reconstruct words based on a drawing of the container’s contents. This is vocabulary association and visual memorization. The act of “clicking on the box image speaks the word” ties auditory and visual processing. Thematically, it’s about order and identification—restoring semantic meaning from fragmented literal components, a foundational spelling skill.

2. The Submarine Radio Station (Garbled Transmissions): Here, words are textually scrambled. The player must sort mixed letters. Initially aided by image and audio clues, the challenge escalates by removing the visual aid. This is phonemic awareness and orthographic mapping. The submarine setting implies communication over distance, where clarity is paramount—a perfect metaphor for the decoding process. It teaches that the sound of a word (the transmission) must be matched to its correct written form (the cleared signal).

3. The Old Prison (Cell-Block Crosswords): Players start with one word and use image clues to solve adjacent, crossword-style patterns. This is contextual spelling and morphological understanding. The prison bars metaphorically represent the “confining” rules of spelling; to break out (solve the puzzle), one must understand how words interlock, sharing roots, prefixes, or suffixes. It moving beyond single words to the architecture of language.

The Unifying Narrative Thread: All these activities are framed by the guidance of Kusin Vitamin, the series’ iconic guide. His presence bridges the gap between game and story. He is not a dry tutor but a whimsical uncle figure, embodying the series’ tone of gentle, curious adventure. The narrative theme is one of exploration and restoration. The player, as an invisible helper, restores order to a busy, slightly chaotic waterfront world by mastering the fundamental tools of written communication. It’s a subtle but powerful message: literacy is the key to navigating, understanding, and fixing your world.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Pedagogical Design in Disguise

Core Loop and Structure: The gameplay is a cycle of story cutscene → mini-game → rewards/next story beat. This structure leverages the “goal-gradient effect”; the narrative provides the “why,” the mini-game the “how.” The three difficulty settings, as per the MobyGames description, are crucial. They likely adjust word length, complexity of spelling rules (e.g., long/short vowels, consonant doubling), and the removal of visual aids (as seen in the radio game’s progression). This allows the game to grow with the child, a vital feature for sustained engagement.

The Six Mini-Games: While three primary activities are described, the MobyGames spec mentions “six different games.” This suggests either variations on the three core types (e.g., different vocabulary sets or rule focuses for each difficulty) or two additional distinct activities not detailed in the provided sources. Given the meticulous design, it’s plausible these six are carefully graduated challenges targeting specific sub-skills: phoneme-grapheme correspondence, common rule application (like “i before e except after c”), suffix/prefix addition, and visual word recognition.

Innovative (for its context) Systems:

* Multi-sensory Input: Every interaction couples text, image, and spoken Swedish. Clicking a picture gives the word’s pronunciation; clicking a letter gives its sound. This triad addresses visual, auditory, and kinesthetic (mouse-click) learning pathways.

* Competitive Cooperation: The 1-2 player mode is significant. It introduces a low-stakes social element. Siblings or friends can compete or collaborate, transforming solitary study into shared play. The “competition” framing, gentle as it likely is, taps into intrinsic motivation.

* Unlocking Creative Tools: The GameArchives source mentions that progress unlocks “creative tools including a sign-maker and story notebook.” This is a brilliant pedagogical capstone. After proving spelling competence in deconstructed contexts, the child is given tools to apply that competence creatively. The sign-maker allows for emergent word practice (making labels for their own imaginary containers), and the story notebook for writing. This moves from cognitive reception to production, cementing learning.

Flaws and Limitations: By modern standards, the game is rigid. There is no dynamic difficulty adjustment based on performance; the child must manually select a level. Save functionality, as hinted in the GameArchives review, may be limited or absent, relying on completed sessions. The fixed-screen perspective, while thematically consistent, offers no panning or depth. The content, though substantial at ~4000 words, is finite. These are not failures of design but artifacts of the CD-ROM medium’s limitations and the era’s understanding of “replayability” in educational contexts, where completion was often seen as a terminus.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Näppelunda Aesthetic

Visual Design and Artistic Direction: The art style is directly inherited from Lennart Hellsing’s illustrations—warm, cartoonish, and distinctly Swedish. The character of Kusin Vitamin, with his exaggerated features and whimsical clothing, is a direct translation from page to pixel. The backgrounds, while static, are richly detailed watercolor-esque renderings of a bustling, friendly waterfront. The warehouse is cluttered but organized; the radio station is cozy and technical; the prison is old but not frightening. This creates a safe, exploratory atmosphere. The world feels lived-in and coherent, not a sterile menu backdrop. The “fixed/flip-screen” design means each location is a carefully composed diorama, encouraging the child to scan the entire screen for interactive elements, a subtle lesson in environmental observation.

Sound Design and Music: The fully voiced Swedish dialogue is the game’s auditory crown jewel. It provides authentic pronunciation modeling—absolutely critical for a spelling game. Kusin Vitamin’s voice likely carries a warm, encouraging tone. Sound effects are functional and thematic: the clunk of a container, the static and beeps of the radio, the clank of a prison cell door. The background music is cheerful, melodic, and unobtrusive, maintaining a positive, focused mood without distracting from the cognitive task. The soundscape doesn’t just decorate; it reinforces the setting and provides auditory feedback for every action, creating a tightly coupled sensory experience.

Reception & Legacy: A Quiet Success in a Niche

Critical and Commercial Reception: Formal critic reviews appear non-existent in the aggregated databases (Metacritic, MobyGames show none). Its commercial life was likely projected through educational catalog sales, direct marketing to Swedish schools, and retail presence in the “edutainment” section. Its inclusion in a series (“Krakels ABC”) and the fact it was published on multiple platforms (Windows, Mac, Windows 16-bit) and even received an XP update patch (per redump.org) suggests it was a stable, successful product within its target market. The scarcity of user reviews on platforms like Metacritic is typical for non-mainstream, region-specific educational titles; its “reviews” are more likely found in Swedish-era teaching publications or parent-teacher bulletins.

Legacy and Influence: Jag kan stava’s legacy is regional, pedagogical, and archetypal.

1. Cultural Specificity: It stands as a prime example of localized educational game design done right. Instead of translating a generic American product, it built upon a cherished Swedish IP. This ensured not just linguistic accuracy but cultural resonance—the humor, the settings, the character archetypes all spoke directly to its young Swedish audience. This model contrasts with the global, often culturally-neutral approach of competitors like Reader Rabbit.

2. Pedagogical Archetype: It crystallized a highly effective template for literacy games: narrative framing + graduated mini-games targeting discrete skills + multi-sensory feedback + creative application phase. Many successful later titles, like the Brain Age series (though for different skills) or Carmen Sandiego word games, follow a similar “adventure hook for practice” structure.

3. Historical Document: As a CD-ROM title from 1998, it captures the peak ambition of pre-internet educational multimedia—a self-contained, voice-acted, graphically polished world on a single disc. Its existence is a data point in the history of how literacy was digitally taught before web-based adaptive learning platforms.

4. Influence on Regional Development: Its success within the “Krakels ABC” series likely paved the way for further Swedish-developed educational software, proving a market for high-quality, home-grown products that could compete with imports.

Conclusion: An Imperfect Beacon

Jag kan stava is not a forgotten masterpiece awaiting rediscovery by indie game enthusiasts. It is, however, an exemplary case study in purposeful, culturally-attuned educational game design. Its technical limitations are glaring today, but within the constraints of 1998’s CD-ROM technology and its narrow pedagogical goals, it is remarkably coherent. The game understands that for a child, learning to spell is not an abstract mental exercise but a social and practical key. By embedding that key within the charming, recognizable world of Näppelunda and the guidance of Kusin Vitamin, it made the practice feel like play and the success feel meaningful.

Its place in video game history is not on a list of influential mechanics or best-sellers, but in the pedagogical canon. It represents a sincere, well-executed effort to harness interactive media for a fundamental academic skill, respecting the intelligence of its young players and the integrity of its source material. For historians, it is a touchstone for Nordic edutainment and the licensing of literary properties in the 1990s. For educators then and now, it remains a potent reminder that the most effective learning tools are those that understand the context of the learner—their language, their culture, their need for narrative purpose. Jag kan stava may not have spawned a genre, but it perfectly executed one: the Swedish spelling adventure. In that, it is an undeniable, if quiet, success.