- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Art Games

- Developer: Art Games

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Avoiding hostile animals, Collecting, Finding keys, Jumping, Opening chests, Platform, Using objects

- Setting: Woods

Description

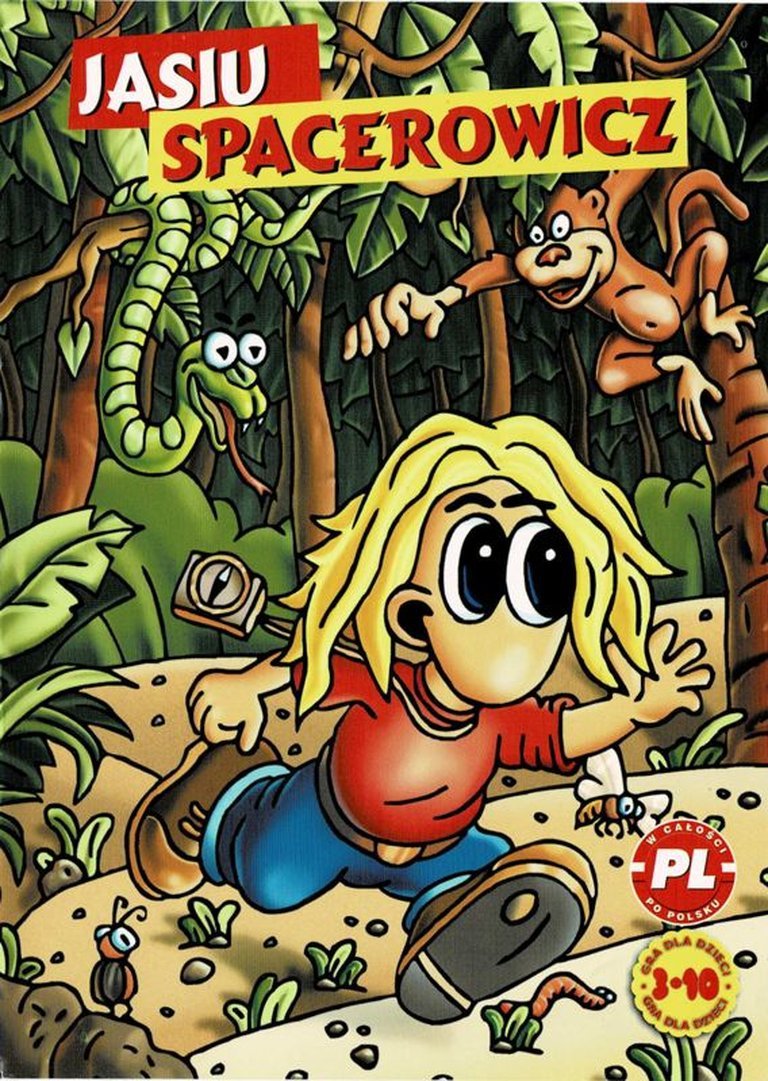

Jasiu Spacerowicz is a 2D side-scrolling platformer released in 2002 by Art Games, set in a mystical forest where a young boy named Jasiu embarks on a quest to discover why the animals have changed in behavior. The game combines classic platforming mechanics—jumping, walking, and collecting objects—with puzzle-solving elements, as players must find keys and open magic chests to progress through each of the six levels. Along the way, Jasiu encounters hazards like falling stones, bonfires, and hostile animals that drain energy, while apples and power-ups restore health or grant abilities like a long jump. Vibrant 2D visuals, Polish folklore-inspired atmosphere, and a soundtrack by Marcin Andrzejewski and Marek Raczycki complete the charming, albeit simple, action-adventure experience aimed primarily at younger audiences.

Jasiu Spacerowicz: Review

Introduction: A Forgotten Platformer in the Shadow of Greater Tales

In the vast and ever-expanding pantheon of video games, very few titles are remembered for their presence rather than their innovation — yet fewer still are remembered at all. Enter Jasiu Spacerowicz, a simple, 2D side-scrolling platformer released in 2002 by the small Polish studio Art Games. On the surface, it appears to be little more than a modest, even rudimentary entry in the crowded space of early-2000s home computer platformers. Yet, beneath its unassuming veneer lies a fascinating case study in cultural specificity, regional development history, technological limitations, and the fine line between homage and copyright infringement. Commercially obscure, critically overlooked, and surviving primarily as a cult archival curiosity, Jasiu Spacerowicz is not a masterpiece — but it is a mirror.

This review posits that Jasiu Spacerowicz holds a unique, if underappreciated, place in video game history precisely because it exemplifies so many forces shaping Eastern European indie development in the post-communist transition: limited resources, creative improvisation, familiarity with Western titles through bootleg channels, and a desire to tell local stories with global mechanics. While its gameplay is straightforward to the point of charm, its narrative ambitions, visual personality, and reception history — including accusations of being a “ripoff” of Psygnosis’ Lomax — offer a far richer tapestry than its six-level structure might suggest.

This is not a game about saving a princess or defeating a cosmic evil. It is a child’s journey through a changing forest, a metaphor for ecological anxiety, childhood discovery, and the loss of innocence — all wrapped in a distinctly Polish cultural sensibility. In analyzing Jasiu Spacerowicz, we are not merely assessing a game; we are excavating a moment in a nation’s digital childhood.

Development History & Context: The Polish Post-Industrial Indie Scene

The Studio: Art Games and the Early 2000s Polish Landscape

Art Games, the developer and publisher of Jasiu Spacerowicz, was not a seasoned industry giant. It was a small, likely self-funded or minimally capitalized team operating in Poland during a transitional decade. In the early 2000s, Poland was still recovering from the economic and technological upheaval of the post-communist era. The gaming industry was nascent, with few local studios creating titles for international platforms. Most Polish game development at the time consisted of hobbyist projects, educational software, or adaptations of Western IP — often distributed via CD-ROMs bundled with magazines or sold in regionally targeted retail channels.

Art Games fits into this mold: a micro-indie studio with a minimal credit list (just six contributors, as listed on MobyGames), operating without major publisher backing, distribution, or marketing power. The team was multidisciplinary in nature, with a single individual, Piotr Misztal, serving as production lead and engine developer — a common trait in small-scale Eastern European game development, where generalists are the norm.

Technological Constraints and Engine Innovation

Jasiu Spacerowicz was developed for Windows PCs of the early 2000s, meaning it had to run on systems ranging from Pentium II/III processors to early Athlon systems, often with just 128MB of RAM and integrated graphics. This necessitated a lightweight, custom-built engine — a fact confirmed by Misztal’s credit as the engine developer. The game uses a 2D scrolling side-view perspective, rendered in smooth, tile-based environments, with frame-by-frame animation and pixel-art sprites reminiscent of early PlayStation-era platformers.

Despite its simplicity, the engine supports object interaction, hazard management, power-up mechanics, and board-based progression — a significant technical achievement for a team of six, especially without access to pre-built game frameworks like GameMaker (which was still in its infancy) or XNA (not yet available). The absence of source code documentation or post-release patches (none recorded on MobyGames or GameFAQs) suggests a “build and ship” mentality typical of regional commercial CD-ROM titles — games made to fulfill an order, not to be iterated upon.

The Gaming Landscape in 2002: A World of Giants, A Time for Shadows

By 2002, the platformer genre was both massive and in flux. The fifth generation of consoles (PSone, N64) had given way to the sixth (PS2, GameCube, Xbox), and 3D platformers like Super Mario 64, Banjo-Kazooie, and Spyro the Dragon had long since overshadowed their 2D ancestors. On PC, platformers were niche, surviving in the form of:

– Crash Bandicoot ports (still popular in Eastern Europe),

– Spyro: Enter the Dragonfly releases,

– Lomax (1996, PS1),

– Joe & Mac series,

– and various Japanese platformers ported through subsidiaries.

Jasiu Spacerowicz was born in this twilight zone — a time when 2D platforming was no longer trendy but still culturally legible, especially in regions where 3D graphics were prohibitively expensive for local developers. Its release on CD-ROM in Poland (2002, per MobyGames) and wider Europe (2004, per GameFAQs) suggests it was part of a wave of CD-ROM-based “home entertainment” packages — games bundled with digital encyclopedias, encyclopedias, or educational software, aimed at families rather than hardcore gamers.

Crucially, the game’s design sensibilities are not original — a fact highlighted by its infamous resemblance to Lomax, a 1996 Psygnosis/bAba/Bam! Entertainment title. According to the Internet Archive entry (authored by user “fakk3”), Jasiu Spacerowicz:

“resembles the 1996 Lomax game. The main character ‘Jasiu’ resembles a Lemming Lomax. The sounds in the game were also stolen from the Psygnosis game.”

This raises the specter of cultural appropriation, regional development ethics, or outright plagiarism — but to frame it as merely “a ripoff” is to misunderstand the context. In many parts of Eastern Europe during the 1990s and early 2000s, Western titles were often accessible only through bootlegging, demo CDs, or shared floppy disks. Developers like Art Games may have played Lomax on illegally copied discs, learned its mechanics by trial and error, and then adapted them into a local product — not out of malice, but out of creative necessity and limited exposure to development tools.

This is not unique to Poland; it was a common phenomenon across post-Soviet states. What Art Games did was more akin to folk adaptation than criminal piracy — they took a familiar form and filled it with local flavor.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Child’s View of a Changing World

Plot: A Walk in the Woods, But Not Really

The story of Jasiu Spacerowicz is deceptively simple, yet thematically potent. As described in the official description:

“A young boy who tries to find the reason of animals’ character change. The action takes place in the woods.”

Jasiu — a name implying a diminutive, endearing presence, possibly from a local folk term (“Jasiu” being a common Polish pet name or character archetype, akin to “Jimmy” or “Timmy”) — is not a warrior, hero, or adventurer. He is a child, out for a walk, who stumbles into a mystery: the animals of the forest are behaving strangely, dropping apples, hurling stones, or becoming aggressive. His journey is not one of conquest, but of exploration, restoration, and understanding.

The objective is not to defeat a boss or reclaim a stolen artifact, but to wander through six distinct boards, open two required chests per level, collect gold coins, and save the land — a loose framing for what is effectively a puzzle-platformer loop. Yet, the narrative is implied rather than told. There is no cutscene, no dialogue, no text-box exposition — just environmental storytelling and symbolic play.

Characters: Jasiu, the Forest, and the Ghosts of Change

-

Jasiu: A nameless boy in a red cap and simple clothing (similar to a lemming’s silhouette, as noted), he is the everychild. His power-ups (energy-restoring apples, long-jump enhancers) reflect childhood rewards. He does not speak — he acts. His vulnerability to falling stones, bonfires, and animal attacks mirrors a child’s fragility in an unkind world.

-

The Forest: More than a setting, it is a character in transformation. The “change in animal character” is never explained — is it pollution? A curse? Climate shift? A psychological break? This ambiguity is not a flaw, but a thematic strength. The forest is unstable, reflecting anxieties about modernity, environmental degradation, and the loss of tradition — themes resonant in post-communist Poland, where rapid industrialization disrupted rural life.

-

The Chest and the Key: The requirement to open two chests per level with keys introduces a moral dualism. Players must choose which chest to open first, which path to take — not for story, but for gameplay efficiency. Yet, this echoes traditional Slavic folk tales, where choices have consequences, and both paths must sometimes be taken.

Dialogue and Exposition: The Power of Silence

There is no spoken or written dialogue in the game. The narrative exists in:

– The opening image (a boy in the woods),

– The animal behaviors (hostile vs. passive),

– The power-up items (apples = life, stones = danger),

– The progression (each level falls into greater chaos).

This is show, don’t tell, in its purest form. The game implies that the forest is sick — and Jasiu, through his walk, is seeking a cure. But what is the cure? The gold inside the chests, which “save the land.” This is deeply symbolic: reclaiming lost value, restoring harmony through accumulation, completing the journey.

By bypassing exposition, the game aligns itself with children’s literature — the kind of tale where a child walks into a wood and returns having changed, even if they can’t articulate why.

Themes: Ecological Anxiety, Innocence, and the Local Idiom

-

Ecological Anxiety: The “change” in animals is never explained, but it feels environmental. The falling apples, stones, and bonfires suggest a world turning hostile. This resonates with global concerns in the early 2000s — climate change, deforestation, urban sprawl — but refracted through a Central European lens, where agricultural forests were being replaced by concrete.

-

Innocence and Perspective: Jasiu is small, slow, and unpowered. He is not a superhero. The game’s difficulty ramps slowly, mirroring a child’s growing competence. The red and blue items are color-coded, like simple educational tools — this is a game designed to be understandable, not overwhelming.

-

The Local Idiom: The title itself — Jasiu Spacerowicz — means “Jasiu the Walker.” “Spacer” in Polish means a stroll, a leisurely walk. This is not a quest, not a battle, but a walk — a very Polish, very human, very ordinary act elevated into a journey. In a world of epic narratives, this anti-epic is radical.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Simplicity as Philosophy

Core Loop: Platforming as Ritual

The gameplay loop is straightforward:

1. Navigate a side-scrolling level.

2. Collect keys and gold coins.

3. Avoid hazards (falling apples, stones, animals, bonfires).

4. Open two required chests.

5. Progress to the next level.

6. Repeat across six levels.

There is no final boss, no climax, no direct confrontation. The game ends with the sixth level’s chests opened — likely with a static image of Jasiu walking into the distance.

Movement and Platforming

- Controls: Basic keyboard inputs — left, right, jump. No double-jump, no crouch, no run button. Movement is slow, deliberate, emphasizing exploration over speedrunning.

- Jumping: Predictable arc, but frame-sensitive landing — a missed jump due to timing is common. The blue power-up extends jump distance, providing a crucial but temporary advantage.

- Enemies: Most animals are passive until interacted with (e.g., a deer drops an apple when approached). Some (e.g., a bear) are aggressive. This creates a rhythm of caution and curiosity.

Hazard System: The Grammar of Danger

| Hazard | Effect | Psychological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Falling Apples | Damage | Nature turning on the traveler |

| Falling Stones | Damage | The world’s instability |

| Hostile Animals | Damage | The “character change” theme made tangible |

| Bonfires | Damage | Landmarks becoming threats |

| Red Elements | Restore energy | Hope, safety, small rewards |

| Blue Elements | Extend jump | Temporary empowerment |

This creates a binary system of risk/reward, where the world is split between harm and healing, loss and gain — not through narrative, but through systemic design.

Progression and Puzzle Elements

- Chests and Keys: Two chests per level, gate progress. Keys are scattered, encouraging exploration.

- Energy System: A visible health bar. Losing energy forces retreat or risk.

- Point Collection: Gold coins are worth points, but not required — they are corrective, like collecting pebbles on a walk “because they’re there.”

- Board Design: Levels are non-linear but not open-world. They use ladders, pits, elevators, and locked doors to encourage backtracking — a high-school-level Metroidvania element.

UI and Accessibility

- Simple HUD: Health bar, coin counter, and a “chest open” indicator.

- No tutorial: Players learn through trial, error, and observation.

- Save/load: Likely per-level (inferred from CD-ROM structure), not continuous.

The entire system is accessible to children or casual players, but not easy. It respects the player’s ability to read patterns — a hallmark of good platformer design, even in simplicity.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Forest as Dream and Warning

Art Direction: Charm in Constraint

The visuals are 16-bit-inspired pixel art, with a warm, earthy palette — browns, greens, reds (for Jasiu and red elements), blues (for power-ups). The character sprites are small, elegant, with expressive animations (blinking, leaning, jumping). The environment is hand-drawn and tile-based, with:

– Forests with parallax layers,

– Caves with stone textures,

– Clearings with scattered items.

The art is unapologetically Polish — there are no stylized anime characters or Western fantasy beasts. The animals resemble those from local folklore or rural life — bears, deer, birds. Even the chests look like old wooden crates, not treasure troves.

Atmosphere and Emotion

Despite its technical limitations, the game generates a unique mood:

– Melancholy (wooden structures, empty paths),

– Cautious wonder (when red apples appear),

– Unnerving tension (when stones fall unexpectedly).

This is enhanced by extreme quiet between sound events — a technique used in horror, but here used for emotional resonance.

Sound Design: The Most Controversial Element

And here lies the game’s greatest controversy: the audio.

As noted by the Internet Archive, Jasiu Spacerowicz appears to use sound effects directly sampliled or ripped from Lomax — a claim supported by thematic and stylistic parallels:

– The jumping “boing”,

– The diamond/coin collection “bling”,

– The enemy attack “squawk”.

This is not reuse — it’s covert recycling, possibly done without licensing due to cost or ignorance. The music, composed by Marcin Andrzejewski and Marek Raczycki, is generic chiptune-style platformer music — pleasant but unmemorable, looped per level.

The sound design duality — original music, Lomax-derived effects — creates an uncanny valley of authenticity. The game feels like a Western title, even as its visuals and theme scream “local.”

Yet, this contradiction may be intentional: a translation layer, like watching a Polish film with Czech subtitles. The familiar sounds make the unfamiliar world accessible.

Reception & Legacy: The Unseen Game That Sparked Echoes

Critical and Commercial Reception

- Commercial Reception: Unknown. Sales figures are absent. Likely distributed via Polish CD-ROM retail channels or magazine bundles, with minimal reach.

- Critical Reception: Near-zero contemporary coverage. No Metacritic or MobyGames critic reviews. No major gaming magazine mentions.

- User Reviews: One player rating — 3.0/5.0 — with no comments. Survives in obscurity, known only to archivists and European retro enthusiasts.

The “Lomax” Controversy and Viral Rediscovery

The game’s 2020 restoration on the Internet Archive brought it renewed attention — not for its design, but for its plagiarism allegations. The entry brands it a “bootleg” and “ripoff”:

“The game resembles the 1996 Lomax game. The main character ‘Jasiu’ resembles a Lemming Lomax. The sounds in the game were also stolen from the Psygnosis game.”

This framing — by a Western archivist — is problematic. To call it a “theft” assumes a globalized, IP-protected marketplace that did not exist in Poland in 2002. For Art Games, Lomax may have been the only reference point they had. Their act of mimicry was not theft, but vernacular design — like folk musicians borrowing Western chord progressions.

Influence? Legacy? A Case of Reverse Innovation

Jasiu Spacerowicz did not influence a single major game. It has no sequels, no ports, no spiritual successors. Yet, it prefigures themes that would emerge in the 2010s:

– Environmental storytelling (as in Inside, Limbo),

– Child narrators (as in Little Nightmares),

– Small, meaningful worlds (as in Gris),

– Regional narratives in platformers (e.g., Pnzh: Quest of Human, Ukrainian).

Moreover, it represents a lost tradition — the CD-ROM era of Eastern European game development, where local studios used global mechanics to tell local stories. It is a cousin to games like Knight Lore (atypical setting), Leming (sound theft), and Vampire Savior (cultural export).

Its legacy is archival: a document of time, place, and creative constraint.

Conclusion: The Walk That Wasn’t Required, But Was Needed

Jasiu Spacerowicz is not a good game by modern platformer standards. It lacks depth, innovation, and — arguably — originality. It fails to innovate, fails to excite, fails to tell its story clearly. And yet.

It succeeds in its modest goals: to be a playful, peaceful, slightly eerie walk through a changing wood. It is a children’s game made by adults who remember being children in post-industrial Poland. It is a love letter to the forest, reclamation, and quiet heroism.

Its use of Lomax sounds is ethically ambiguous — but also artistically resonant. It is a cultural echo, a folk adaptation, a translation of form for local content.

In the end, Jasiu Spacerowicz deserves more than dismissal as a “bootleg.” It deserves to be studied, preserved, and understood — not as a masterpiece, but as a mirror. A mirror held up to a nations’ gaming infancy, to the quiet thefts of the under-resourced, to the universal longing to walk into the woods and make things right again.

Verdict:

Not a classic. Not a game for speedrun culture or meta-commentary. But a cultural artifact of the highest importance — a window into the creative struggles and hopes of early Polish game development. In another world, Jasiu might have become a national mascot. In ours, he remains a quiet walker through a forgotten forest.

And perhaps that is the point.

Final Rating: 3.5/5 (as a game). 4.8/5 (as a historical artifact).

Jasiu Spacerowicz is not great because it is good, but because it existed at all — and still does, despite the odds. In that, it is heroic.