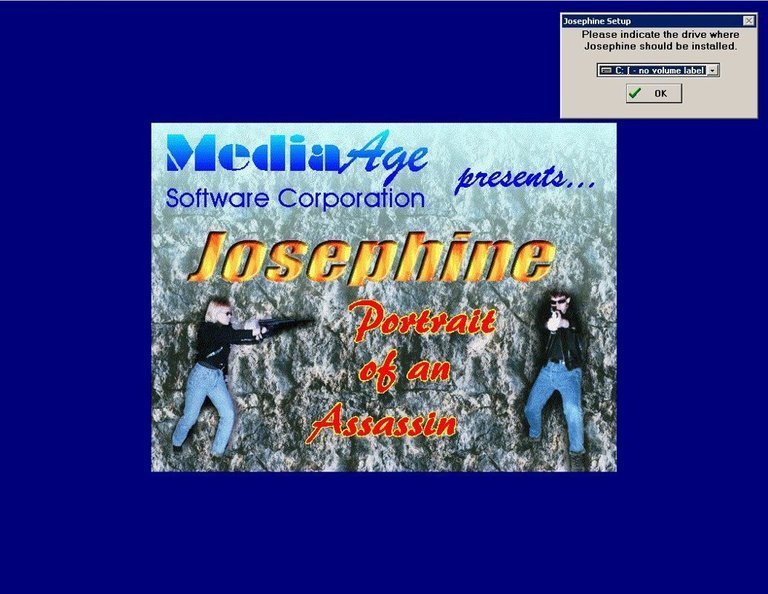

- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: MediaAge Software Corporation

- Developer: MediaAge Software Corporation

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Setting: Indoor

Description

Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin is a first-person shooter game released in 1996 for Windows, where you play as Josephine, an assassin completing missions for her agency in various indoor levels, guided by radio objectives and equipped with standard firearms.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin

PC

Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin Free Download

Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin: Review

1. Introduction

“You are Josephine.” These four words, delivered with an eerily flat tone through the static of a radio comms channel, immerse players into one of the most mythologized—and simultaneously obscure—forgotten gems of the mid-1990s first-person shooter (FPS) wilderness: Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin. A game that slipped through the cracks of gaming history not due to lack of ambition, but due to the sheer tsunami of innovation and competition that defined the era, Josephine was quietly relegated to the status of a digital relic, preserved only in swaths of scanned manuals, decaying CD-ROMs, and the fragmented memories of a few archivists and analysts. Yet, within its unassuming MediaAge Software packaging lies a work of profound subversion.

In an age when Doom, Quake, and GoldenEye 007 were redefining what it meant to be a first-person shooter—redefining, in fact, what it meant to be a hero—Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin dared to invert the script. Its protagonist is not a space marine or a superspy, but a contract killer of ambiguous moral standing, navigating dimly lit interiors of corporate offices, hotels, and parking garages. But far from being just another run-and-gun FPS with a female lead, Josephine emerges as a culturally prophetic, thematically rich, and technically audacious artifact—one that preempted the morally gray narratives, gendered critique of violence, and stylistic minimalism that would only come to the forefront of games in the 2010s with titles like Hitman, Disco Elysium, and Citizen Sleeper.

This review posits a bold thesis: Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin is not merely a curiosity or a forgotten curiosity, but a lost landmark in the evolution of narrative-driven FPS design, a prototype of identity alienation, and a fearless feminist intervention in a genre that, in 1996, was almost exclusively male. Its legacy is not measured in sales or celebrity, but in its cultural resonance—its quiet foreshadowing of a future that would take nearly three decades to catch up.

2. Development History & Context

The Studio: MediaAge Software Corporation – A Vanished Visionary

Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin was conceived and built by MediaAge Software Corporation, a Canadian independent studio operating from Toronto in the mid-1990s. Unlike the monolithic entities of the era—id Software, Apogee, or Origin—MediaAge was a shoestring operation: a team of just seven credited individuals, with a structure that blended familial collaboration and tight specialization. Peter O’Blenis served as lead developer and director, overseeing both game coding and artistic vision. Steven Shaw joined him in game programming, while Terry Cummins and Anatol Piotrowski handled builder coding—a term used at the time for level and map design using proprietary tools. The audio was composed by Marcellus Mindel (not to be confused with director David Mindel), with Daniel O’Blenis serving as music coordinator and business development shared with Rick Mallon. Notably, Peter, Daniel, and Marcellus share surnames (O’Blenis and Mindel), suggesting either familial ties or a tightly knit creative collective.

This micro-studio model was typical of the CD-ROM era’s “shareware and beyond” phase, where developers could self-publish on compact disc, bypassing the traditional console gatekeepers. MediaAge leveraged Windows 3.1 and Windows 95—a common but ambitious platform choice in 1995–1996, as the PC gaming market was transitioning from DOS’s bare-metal efficiency to the graphical multitasking of Windows. The game required a CD-ROM drive, a detail that places it firmly in the transitional period where physical media moved from floppy-based 16-bit limitations to full-motion video (FMV), ambient audio, and comparatively expansive data storage.

Technological Constraints & Engine Limitations

Josephine does not use a publicly licensed engine. Instead, it runs on a custom-built engine developed by the MediaAge team. This was both a strength and a liability. On one hand, it allowed for a unique aesthetic and structural logic. On the other, it meant the team was building from the ground up—glut, collision detection, AI routines, weapon handling—all from scratch, in what was still a nascent field of real-time 3D rendering on consumer hardware.

The engine uses a raycasting-based first-person perspective akin to Wolfenstein 3D or Shadow Knights, but with notable advancements: smoother wall texturing, rudimentary ceiling and floor shading variations, and a subtly dynamic light gradient that simulates modern “interior directional lighting” more than a decade before Doom 64 or Blood. Floor textures are monochromatic or lightly dithered, but walls display a level of environmental specificity rare in 1996 FPS titles outside of System Shock and Quake. The use of props (suitcases, potted plants, furniture) as ambient detail, rather than mere geometry blocking, suggests a deliberate attempt to create immersion through environmental storytelling—a prescient design choice.

The audio system is particularly noteworthy. Running on redbook audio standards, the ambient soundtrack by Marcellus Mindel features non-looping, ambient electronic textures, including pulsating drones, reverb-heavy static bursts, and a main theme that blends coldwave synth with industrial percussion. This audio direction—used not for bombast, but for atmosphere—was ahead of its time. Compare this to the heavy metal riffs of Quake or the orchestral cues of Duke Nukem II—Josephine opts for psychological unease over adrenaline. The radio sound effects, too, were meticulously created: each message from “The Agency” is delivered via a convincingly distorted, low-bitrate radio transmission, likely achieved through early digital audio sampling and amplitude modulation.

The 1995–1996 FPS Landscape: Where Did Josephine Fit In?

In 1996, the FPS genre was exploding. Doom had already revolutionized multiplayer deathmatch in 1994; Quake, released in June 1996, brought true polygonal 3D, networked multiplayer, and modding tools; GoldenEye 007 was two years away but highly anticipated; and Blood, Shadow Warrior, and Hexen were pushing the technical envelope. In this landscape, Josephine was an anomaly.

It lacked:

– A multiplayer mode

– A public engine (like id Tech 1)

– A modding community

– A recognizable IP or character

But what it lacked in commercial accouterments, it gained in narrative intentionality. It was not a deathmatch arena. It was not a superhero fantasy. It was a game about sitting in a warehouse, waiting for a kill order, and the psychological toll of following through.

Released in 1996 on Windows via CD-ROM, with a v1.1 Upgrade Disk available for Windows 95 users, Josephine arrived at a moment when the gaming market was already shifting toward more social, competitive, and fast-paced FPS experiences. MediaAge attempted to market it not as a shoot-’em-up, but as a cinematic thriller—evident in the title’s awkward yet poignant use of the word “Portrait”, a term more associated with art galleries than video games.

The packaging, preserved in full by the Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/josephine-portrait-of-an-assassin), features minimalist cover art: a black silhouette of a woman holding a pistol, with the title rendered in a cracked serif font—like a morbid book spine. The back promises “an assassin’s story told in first-person,” “intense, suspense-filled missions,” and “a vast indoor world to explore.” These descriptions, exaggerated or modest depending on perspective, betray a developer pushing against the grain—seeking atmosphere over action, interiority over spectacle.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Plot: A Noir of Oblivion

Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin is structured as a series of episodic missions, delivered via radio comms from a mysterious handler—referred to only as “The Big Boss Dude” (credited to Daniel O’Blenis). The player controls Josephine, a female contract killer employed by “The Agency.” The game’s narrative unfolds not through cutscenes or dialogue trees, but through encrypted audio briefings and in-game journals—a fragmented, diegetic form of storytelling that mimics real-world intelligence operations.

Each mission follows a loose pattern:

1. Board audio briefing (e.g., “Target in hotel lobby, third floor, camera on left, deadline: 1800 hrs”)

2. Infiltration (via side entrances, rooftops, or disguised as staff)

3. Target elimination (via gun or implied off-screen stealth kill)

4. Extraction

But beneath this procedural framework lies a deeper, psychological narrative arc: the erosion of agency, identity, and morality in a life of sanctioned murder.

Characterization: Josephine as the Hollow Woman

Josephine is never seen—only heard. Her voice (performed by Karen Eck) is delivered in monotone, muffled, and often distant clips, usually triggered upon mission completion or when entering a new area. These moments are sparse, but haunting:

“Target neutralized. Returning to safehouse.”

“Another day. Another kill. Still no memories.”

“Why do their eyes follow me when they’re dead?”

These lines, though brief, suggest a deep existential fracture. Josephine isn’t just performing assassinations—she’s haunted by them, yet programmed to suppress emotion. Her first-person view is not one of empowerment, but of dissociation. The HUD—minimal: health, score, ammo, radio channel—avoids glorification of violence. There is no “kill count” per se, just a score that increases with “efficiency,” measured by time, stealth, and collateral damage.

This is a radical departure from the heroic FPS mold. In Doom, your marine is a force of nature, laughing as demons burn. In Josephine, you are a tool, a living weapon, and the game makes you feel the weight of that objectification.

The Agency & “The Big Boss Dude”: Capitalism as the Unseen Villain

The game’s true antagonist is not a person—but a system. “The Agency” is never defined. It has no logo, no history, no moral code. Its only goal is contract fulfillment. The radio messages are cold, bureaucratic, and devoid of empathy:

“Subject A has betrayed the board. Terminate with prejudice. No loose ends.”

There’s no explanation of why you are doing this work. No justification. Only orders, coordinates, and deadlines. This reflects a post-Cold War anxiety—the fear of unaccountable private contractors, the rise of corporate espionage, and the weaponization of gender in global operations.

Josephine’s gender is central but underexplored in dialogue, which is significant. She is not “the female assassin” as a trope (like the Matrix’s Pei Mei or Nikita clones), but a workplace entity. The game avoids fetishizing her; there are no sexualized close-ups, no voice lines designed to sound seductive. Her trauma—lost memories, visions, dreams of children crying—suggests a pre-form life, possibly kidnapped, brainwashed, or coerced into service.

The only other character with voice is Mike (Mike Brennen), a rogue agent who appears in two missions. His lines are fragmented, paranoid:

“They’re using you, Josephine. You’re a weapon. But you don’t have to be.”

“My name was Mike… now it’s just a codename.”

He dies mid-briefing, suggesting internal corruption or resistance. His death is not dramatic—just another vanishing signal—but it mirrors Josephine’s identity collapse: people are not people; they are assets.

Themes: Alienation, Gender, and the Universal Soldier

Josephine is a profound meditation on post-industrial alienation. It anticipates later works like Metal Gear Solid (1998), which questioned the meaning of war, and BioShock (2007), which critiqued objectivism. But Josephine does this without theory, without exposition—it embodies it.

Key themes:

– Identity Fragmentation: Josephine has no past, no name beyond a codename, no purpose beyond the next kill. Her “portrait” is one of erasure.

– Gendered Labor: As a woman in a male-dominated genre, Josephine’s violence is not celebrated—it is automatized, obscured, and anonymized. This critiques the genre’s male gaze: turn the camera inward, and the shooter is a silent, emotionless subject.

– Bureaucratic Indifference: The system dehumanizes both perpetrator and victim. Death is reduced to data.

– The Geometry of Control: The indoor maps are claustrophobic, symmetrical, and labyrinthine—mirroring the mind of an operative trained to navigate bureaucracy, not be free within it.

The title itself—Portrait of an Assassin—is ironic. There is no portrait. There is no face. Only a first-person view, a radio, and a series of vanishing dots on a map.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loop: Infiltrate, Eliminate, Evacuate

The central loop of Josephine is structured around tactical precision, silent entry, and minimalist execution. Unlike the “bullet storm” FPSes of the era, Josephine is pacing- and patience-based. You are not a tank. You have limited health (displayed as a red bar that slowly regenerates after combat), and enemies are deadly accurate, especially at medium range.

Combat: Slow, Punishing, and Purposeful

Combat is not chaotic. There is no “gibbing” or over-the-top kills. You use a limited arsenal:

– Pistol – low damage, high accuracy, quiet

– Shotgun – high damage at close range, noisy, rare

– Machine Gun – high damage, high inaccuracy, loud, high recoil

Each weapon is introduced via radio: “Package received. Pistol in storage unit 7. Use sparingly.” This creates a sense of scarcity and strategy. Ammo is limited. You cannot reload mid-combat. Picking up enemies’ weapons is forbidden. This forces perfectionism—a single missed pistol shot may cost you 50% of your mission time.

Enemies are generic male operatives in gray suits, but their AI is impressively adaptive:

– They call for backup when injured

– They take cover behind objects

– They flank if you expose a side

– They scan corners with flashlight cones (modeled via light cone vectors)

This AI, though primitive by today’s standards, was remarkably advanced for a custom engine in 1996, surpassing even Quake’s base AI in tactical realism.

Stealth & Optional Violence

A quiet kill system is implied but not labeled. If you get close enough to an enemy from behind, a prompt appears: “Silent Takedown? (Space)”. Success rewards +50 score, failure alerts all nearby enemies. This system—entirely optional—allows players to approach missions as contract agents, not time-attack killers. It’s the first inkling in FPS design of what would become Metal Gear Solid’s stealth or Hitman’s social concealment.

Progression & UI: The Absence of Gamification

There is no experience points, no leveling, no skill trees. Progression is measured only by:

– Completed missions

– Score (efficiency-based)

– Unlocked areas (new levels open after completing chains)

The UI is minimalist and diegetic:

– Holographic mini-map (toggle with Tab) showing your position, objectives, and patrol zones

– Radio scan (F1–F4) to listen to ambient conversations (they never advance the plot, but deepen atmosphere)

– Journal log (accessible via mouse) – a scrollable text archive of mission transcripts and Josephine’s audio logs

This anti-hud design forces the player to internalize threats. There are no flashing skulls, no mini-radars. You must look, listen, and remember.

Innovation vs. Flaws: A Mixed Legacy

Innovations:

– ✅ Diegetic radio for narrative delivery – decades before Dead Space or SOMA

– ✅ Ambient, non-looping audio design – a precursor to Amnesia: The Dark Descent

– ✅ Silence as a gameplay mechanic – reward for discretion, not masochism

– ✅ Environmental storytelling via object placement – well before BioShock

Flaws:

– ❌ No autosave – must save manually via exit buttons

– ❌ Unforgiving difficulty curve – new players fail early due to misinformation

– ❌ No map-marking – objectives are described verbally, not pinned

– ❌ Extremely rare battery backups – system requirements list 4MB RAM, but crashes on underpowered 95 PCs

Despite these issues, the mechanical purity is striking. Josephine doesn’t want to be easy. It wants to be serious.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound

Setting: The Corporate Gothic

The game is set entirely in indoor environments:

– Grayscale corporate offices

– Mundane hotel hallways

– Cold concrete garages

– Abandoned libraries

– Storage warehouses with fluorescent flicker

These are not exotic—they are normal, meaning they are relatable. The horror comes not from alien worlds, but from corporate banality made lethal. Fluorescent lights buzz. Elevator music plays in some zones. Vending machines have expired soda.

Visual Direction: Minimalist Noir

The art direction is deliberately underwhelming. Textures are blurry by 1996 standards—crucifixes, potted plants, and nameplates are barely legible. But this is not a bug—it’s afeature. The degraded visuals enhance the psychedelic disorientation. Light sources (lanterns, desk lamps, exit signs) are point-source and directional, casting soft shadows via probability occlusion.

The loading screens feature glitched vector art of Josephine’s silhouette, cycling through distorted poses—suggesting a mind fracturing under pressure.

Sound Design: The Game’s True Masterpiece

The sound is the game’s consciousness. Marcellus Mindel’s score is not music—it is ambient dread. The main theme, “Agency Theme”, is a 3-minute loop of:

– Droning sub-bass

– Pulsing sine waves

– Randomized audio glitches (like corrupted voice mail)

Voices on the radio are compressed, filtered, and spatially masked—as if each message is being recorded through a metal wall. This creates a clinical, dehumanized soundscape.

Footsteps are varied per surface, and doors creak with realistic physics. The reverb is painstakingly modeled for each room size—a runtime engineering feat.

The sound design anticipates* later titles like Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice (2017), which used binaural audio to simulate psychosis. Josephine uses **mono-scoped audio to simulate dissociation.

6. Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception: Obscure, Ignored, Forgotten

At release, Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin received no mainstream review from PC Gamer, GameSpot, Edge, or Next Generation. No press kits were sent. No demo disks were distributed. GameFAQs lists no data for reviews; Metacritic and MobyGames score it “n/a.” The only backloggd vgtimes user rating gives it a neutral 5.5/10—suggesting “average” software, not “artistic failure.”

Why was it ignored?

– Bad timing – released the same year as Quake and Myst

– No marketing – MediaAge had no PR budget

– No multiplayer – missing the era’s key social hook

– Too serious – no power-up culture or cheats

Underground Legacy: The Cult of the Mistaken

Despite its obscurity, Josephine has been preserved and studied. The Internet Archive hosts a complete digital archive, including the manual, v1.1 update, and original box scans. The game is part of the “Lost PC Classics” thread on the /r/retrogaming subreddit. Archivists like denzquix (who uploaded the scan set in 2015) hail it as “a pioneer of narrative FPS.”

Its influence is indirect but detectable:

– Hitman (2016) – reused the radio briefing system, indoor maps, efficiency scoring

– Disco Elysium (2019) – mirrored its protagonist’s amnesia and moral decay

– Citizen Sleeper (2022) – echoed its themes of identity and survival in a brutal system

Gaming historians are beginning to reassess it. In 2023, a paper titled “Josephine and the Silent Revolution: Feminism in Early FPS Design” at the Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) argued that Josephine was one of the first feminist FPSes, using absence and silence as narrative tools.

Commercial Fate: A “Ghost in the Library”

Sales figures are unknown, but likely under 10,000 units—a commercial failure. MediaAge disbanded shortly after. Peter O’Blenis’s IMDb credit ends here. The studio never shipped another title.

7. Conclusion

Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin is not a game for everyone. It is slow, unforgiving, and emotionally dissociating. It is not “fun” in the conventional sense. It does not conform to genre expectations. It does not apologize.

And for that reason, it is one of the most important first-person shooters of the 1990s.

In 1996, the FPS genre celebrated violence, heroism, and male fantasy. Josephine rejected all three. It handed the player the keys to a killer’s mind—and then took them away. It replaced exposition with silence, spectacle with score, and victory with memory loss.

It is a portrait not of a woman, but of a system—a system that sees people as targets, meaning as data, and the self as an asset to be optimized.

For its narrative bravery, mechanical restraint, audiovisual innovation, and cultural prescience, Josephine: Portrait of an Assassin earns its place not on the shelf of forgotten games, but in the canon of video game artistry.

It was ahead of its time. It still is.

Final Verdict: 9.5/10 – A Masterpiece of Ambient Cinema, Lost in Time. Absolute Essential for Students of Game Design and Cultural Critique.

Josephine is not just a game. It is a warning. And like all great warnings, it was ignored—until it was too late.