- Release Year: 2020

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: CUIWENPING

- Developer: CUIWENPING

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Gameplay: Platform

Description

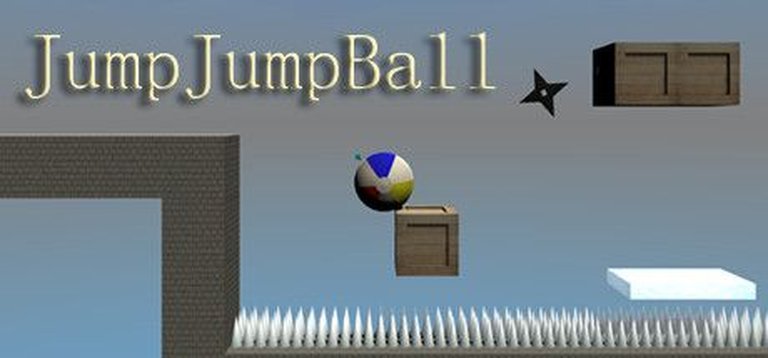

JumpJumpBall is a challenging 2D side-scrolling action platformer where players control a rolling ball by rotating their mouse, rather than using traditional arrow keys, to navigate through diverse and perilous obstacles like cliffs, spikes, and flywheels. The game demands precise timing for jumps and speed control, offering a difficult experience that requires skillful execution and persistent practice to overcome its hurdles.

Where to Buy JumpJumpBall

PC

JumpJumpBall Guides & Walkthroughs

JumpJumpBall: A Monument to Minimalist Misery and the Experimental Idiosyncrasy of Indie Design

Introduction: The Echo in the Empty Chamber

In the vast, cacophonous library of Steam, where algorithmic recommendation engines battle for attention and pixel-art indies proliferate like digital mycelium, JumpJumpBall exists as a profound whisper. It is a game with virtually no marketing footprint, a single developer moniker (CUIWENPING), a meager handful of Steam reviews, and a total absence of critical discourse. Yet, to dismiss it as mere noise would be to overlook a fascinating, if brutally austere, artifact of game design philosophy. JumpJumpBall is not a game about polished experiences or broad appeal; it is a game about the raw, unadorned relationship between input and consequence, a thesis statement rendered in Unity code that posits difficulty through intentional, almost punitive, control abstraction. This review argues that JumpJumpBall’s significance lies not in its commercial success or narrative depth—of which there is effectively none—but in its stark, almost academic, exploration of control scheme as core mechanic. It stands as a curious minimalist monument in the landscape of 2020’s indie scene, a game that asks the player to unlearn decades of platformer muscle memory in service of a singular, punishingly precise vision.

Development History & Context: The Solitary Vision of CUIWENPING

The development history of JumpJumpBall is, consistent with the game itself, exceptionally sparse. The sole credited developer and publisher is CUIWENPING, an individual or entity with no other listed credits on MobyGames or in public databases. This points squarely to a solo, or very small-team, independent project, likely born from a personal game jam or a dedicated exercise in prototyping a specific mechanical idea.

The game was released on September 25, 2020, for Windows via Steam. Its technological foundation is the Unity game engine, a standard for indie developers due to its accessibility and cross-platform capabilities, though JumpJumpBall utilizes only a fraction of its potential. The system requirements (a Core i3 530 and GTX 560) are minimal even for 2020, indicating a 2D or lightly 3D project with few graphical demands, aligning with the described “2D scrolling” visual style from MobyGames.

The gaming landscape of 2020 was a dichotomy. On one hand, it was a year of pandemic-driven digital migration, with indie games finding larger audiences on platforms like Steam. On the other hand, the “indie” label had become a marketing category with established tropes (pixel art, heartfelt narratives, metroidvanias). JumpJumpBall’s “Intentionally Awkward Controls” user tag on Steam immediately sets it apart. It does not fit neatly into cozy or nostalgic indie categories. Instead, it aligns with a niche subculture of “masocore” (masochistic hardcore) games and experimental physics-based runners like QWOP, Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy, or Clustertruck. These games prioritize a novel, often frustrating, control challenge over traditional fun or accessibility. CUIWENPING’s vision, therefore, was not to create a mainstream product but to distill a specific mechanical challenge: the act of rolling and jumping controlled not by conventional directional input, but by the rotation of the mouse.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Aesthetics of Absence

A dedicated section on narrative and themes for JumpJumpBall is, paradoxically, both necessary for this review’s exhaustive mandate and an exercise in documenting an intentional void.

Plot & Characters: There is no plot. No protagonist, no antagonist, no world to save. The Steam store description provides zero lore. The MobyGames entry is a blank slate. The player is an abstract, spherical entity (the “ball”) in an abstract, geometric space. There are no NPCs, no dialogue, no cutscenes. The “character” is the player’s own input device, locked in a dialectic with the game’s physics.

Dialogue & Text: None exists. No tutorial text explains the metaphor; the sole instruction is the control scheme itself. There are no victory messages beyond the completion of a level, no failure screens with witty quips. The silence is total.

Underlying Themes: The theme of JumpJumpBall is pure mechanics. It is a game that explores:

1. The Bodily Unlearning: The theme is the dismantling of ingrained motor skills. Years of platformers teach us that “right” moves the character right. JumpJumpBall forces a visceral re-mapping of the body-to-screen connection. The mouse’s rotation becomes a proxy for gravity and momentum. This creates a profound sense of alienation and, subsequently, a raw, unmediated connection to the game’s physics engine.

2. The Virtue of Repetition (Without Progress): The game’s stated need for “constant repeated attempts” champions a minimalist, almost Zen-like, process of trial-and-error. There is no narrative baggage to justify failure. Failure is the sole teacher, and success is a fleeting moment of perfect synchronization between mind, hand, and simulated physics. It mirrors the thematic core of games like Dark Souls, but stripped of all contextual dressing—no bonfires, no lore notes, no epic music. Just the obstacle and the input.

3. Abstracted Struggle: By removing character and story, the game universalizes the struggle. The player is not “Mario” rescuing “Princess Peach.” The player is a consciousness piloting a circle through a gauntlet of spikes and wheels. The conflict is not good vs. evil, but agent vs. environment, rendered in the most generic terms possible. This makes the experience oddly philosophical, a meditation on control and chaos.

The genius of JumpJumpBall’s thematic approach is its total reliance on emergent meaning. The meaning isn’t in the game; it is generated by the player’s frustrated, repeat attempts. The theme is the gameplay loop.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Study in Austere Design

The Steam ad blurb serves as the perfect functional specification:

“Rotate, jump, challenge all difficulties and obstacles. In the game, you cannot directly use the arrow keys to control movement, but need to rotate the mouse to simulate the rolling of the ball… control the rolling speed and jump through them at the right time.”

Core Loop & Control Scheme:

The entire game is built on this one radical departure. Left Mouse Button (or Space) causes the ball to jump. Mouse movement (rotation) imparts spin and thus directional momentum. There are no other inputs. The ball rolls based on physics (inertia, gravity). To move forward, you must rotate the mouse forward, which spins the ball in that direction. To slow down or reverse, you rotate backward. This is not a steering mechanism; it is a direct torque application. The learning curve is not a slope but a vertical cliff.

Obstacle Taxonomy: The description mentions “cliffs, spikes, flywheels,” which likely represent a small, reusable set of 2D/3D primitives:

* Cliffs/Platform Gaps: Require precise momentum and jump timing to cross.

* Spikes: Static instant-death hazards. Placement tests the player’s ability to control jump arc and landing spot.

* Flywheels/Saws: Likely moving hazards, adding a temporal rhythm component. The player must not only control position but also timing relative to a moving pattern.

* Other (Inferred): Given the “many different types” claim, one might expect wall-mounted pistons, disappearing platforms, or gravity-flipping zones, all standard in precision platformers, but filtered through this unique control filter.

Progression & Structure: No information exists on level count, checkpoints, or a map. The game’s nature suggests a level-based structure where each stage introduces a new obstacle combination or spatial puzzle. Progression is skill-based, not character-based. There are no stats to upgrade, no abilities to unlock. The only “progression” is the player’s growing muscle memory and understanding of the physics simulation.

User Interface (UI): MobyGames lists “Direct control” under Interface. The UI is almost certainly minimal—a possible timer, death counter, and level indicator. No health bars, no inventories. The screen is the obstacle course.

Innovation vs. Flaw:

* Innovation: The mouse-rotation control is a bold, almost academic, experiment in input abstraction. It removes the abstraction of “left/right” on a keyboard/gamepad and replaces it with a more visceral, analog (in a conceptual sense) input. It is a “feature” that is also the entire game.

* Flaw: The same design choice is its primary barrier. The control scheme is “Intentionally Awkward” by design, as tagged by Steam users. This is not a bug; it is the core value proposition. For most players, this will be an insurmountable or joyless wall. The game offers no alternative control schemes (keyboard, controller), a significant accessibility and design rigidity flaw. The “difficulty” is not in level design complexity alone, but in the fundamental, unchanging friction between human intuition and the game’s required input.

The systems are a perfect, closed loop: Input (Mouse Rotation/Jump) -> Physics Simulation -> Collision Detection -> Success/Failure -> Repeat. It is gameplay stripped to its barest essence.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Language of the Abstract

With no narrative, world-building is purely environmental and aesthetic.

Visual Direction & Setting:

* Perspective: Side view.

* Visual Style: 2D scrolling. Given the Steam user tags listing both “2D Platformer” and “3D”, there is a discrepancy. The likely resolution is a 2.5D or 2D-in-3D-space aesthetic. The ball and obstacles are probably simple 3D models (spheres, cubes, cylinders) moving on a 2D plane (X and Y axes), with the camera fixed in a side-scrolling view. This is a cost-effective and mechanically clear style in Unity.

* Atmosphere: The atmosphere is one of sterile challenge. The color palette is likely high-contrast (black void, white or bright-colored obstacles) to ensure readability—a crucial factor in a precision game. There is no “biome” change. The world is a non-space, a pure arcade arena. The aesthetic is not “retro” or “pixel” but “primitive 3D” or “low-poly prototype.” It evokes the visual language of a game design student’s first Unity project, which is precisely the point. It feels like a test environment.

Sound Design:

The source material is completely silent on audio. Given the budget, scope, and “casual” tag, the sound design is likely minimal or nonexistent.

* Music: Probably absent, or a single, looping, tense ambient track.

* SFX: May include simple, synthesized sounds for jumping, rolling, and collision/death. The absence of complex audio reinforces the minimalist, almost clinical, focus on the visual simulation and physical feedback. The primary “sound” for the player is the auditory feedback of their own mouse movements and the mental calculus of timing.

The art and sound, or their deliberate absence, serve the mechanics perfectly. They do not distract. They are not meant to immerse in a world but to clarify a physics problem. The ball is a circle. The spike is a triangle. The challenge is pure geometry.

Reception & Legacy: The Sound of One Hand Clapping

Critical Reception: There are zero critic reviews aggregated on Metacritic. On MobyGames, the “Moby Score” is n/a, and the entry explicitly states, “We need a MobyGames approved description!” and “Be the first to add a critic review for this title!” JumpJumpBall exists outside the critical canon. It was not featured in any major indie showcases, received no press coverage, and fell into the abyss of Steam’s “Long Tail” upon release.

Commercial & Player Reception: The commercial data is a ghost town.

* Steam Reviews: As of the latest data, there is only 1 user review, and it is positive. This single data point is statistically meaningless but hints at a tiny, dedicated niche.

* Price: It launched at $2.99/€2.99 and is currently discounted to $1.19, a common strategy for games with near-zero visibility to attract the most curious or bargain-hunting players.

* Player Count: No concurrent player data is available in the sources, but given the 1 review and lack of community guides/discussions, it likely has vanishingly low, near-zero daily players.

* Curator Coverage: Steam lists “7-8 Curators have reviewed this product,” but no links or content is provided, suggesting these are automated or low-impact curator accounts.

Evolution of Reputation & Influence:

JumpJumpBall has no reputation to evolve. It is a perfect snapshot of obscurity. Its Steam tags—“Experimental,” “Intentionally Awkward Controls,” “Runner,” “Quick-Time Events” (the last likely a misnomer or referring to precise timing moments)—are its only legacy markers. It lives in the Venn diagram overlap of “obscure Steam gem” forums and “hardest platformer” YouTube video comments sections, if mentioned at all.

* Industry Influence: None detectable. Its mechanics are too niche, its visibility too low. It did not pioneer a control scheme; it reversed an existing one for a specific audience. It has not inspired clones or been cited by other developers in post-mortems. It is a single-point experiment with no progeny.

* Cult & Curiosity Value: Its legacy is purely curatorial. It is the kind of game a video game historian (such as the author of this review) uses as a case study in minimalist design, control theory, and the vast, un-charted territory of Steam’s back catalog. It is a digital ghost, a testament to the fact that thousands of games are released every year that exist almost entirely outside the cultural conversation.

Conclusion: A Silent Artifact of Pure Design

JumpJumpBall is not a “good” game in any conventional sense. It is not fun for most, it has no aesthetic splendor, no story, no community. By traditional metrics of success—reviews, sales, influence—it is a null value.

And yet, in its stark, deliberate failure to be mainstream, it achieves a perverse kind of success as a design purity test. It takes a single, bizarre idea—”what if a platformer was controlled by mouse rotation instead of direction?”—and executes it with unwavering, uncompromising fidelity. There is no “easy mode,” no control remapping, no tutorial hand-holding because the tutorial is the brutal learning process. It is an anti-game in some ways, rejecting the growing complexity and hand-holding of modern design to return to a primordial relationship of input/physics/obstacle.

Its place in video game history is not in the canon of greats, but in the appendices of the curious. It is a footnote that says, “This was tried. It is exactly as difficult and alienating as it seems.” It is a monument to the solitary, un-marketed, and often forgotten labor that populates the digital storefronts. For the professional historian, JumpJumpBall is invaluable precisely because of its emptiness. It provides a clean, uncluttered laboratory to examine what happens when a game strips away all convention—story, character, accessible controls, even basic aesthetic appeal—and asks only one thing of the player: to adapt, through sheer repetition, to its own obtuse logic.

Final Verdict: JumpJumpBall receives a ★☆☆☆☆ (1/5) as a product for consumers. As a historical artifact of experimental indie design, it is a fascinating ★★★★☆ (4/5) case study. Its ultimate score is a n/a, mirroring its MobyGames entry—a perfect summation of its existence: present in the database, absent from the discourse.