- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Vivendi Universal Games, Inc.

- Genre: Action, Puzzle

- Perspective: Side view, Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Maze navigation, Robot Customization, Tile matching puzzle

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

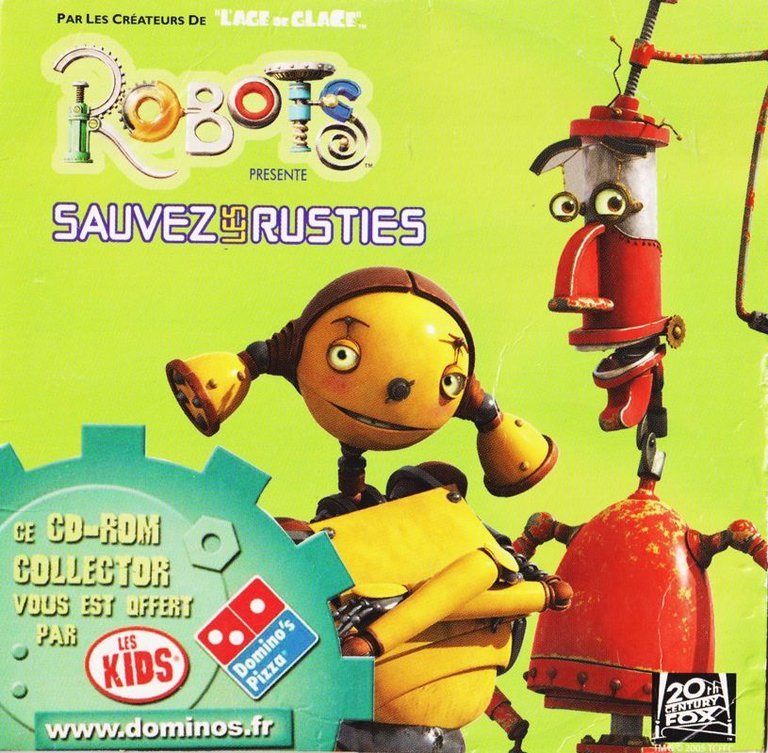

Kellogg’s Pop-Tarts Presents Rescue the Rusties is a 2005 freeware promotional game packaged with Pop-Tarts to advertise the ‘Robots’ movie. Set in a sci-fi futuristic world, it combines three activities: ‘Rescue The Rusties,’ a maze-based game where players save characters from robots using oil; ‘Pick-A-Part,’ a match-3 puzzle involving colored gears; and the ‘Bot Factory,’ a customization feature for building and painting robots.

Kellogg’s Pop-Tarts Presents Rescue the Rusties Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : Perfect for movie fans, puzzle enthusiasts, and dreamers of all ages, this promotional disc packs three distinct activities into one can’t-miss package—powered by Pop-Tarts and inspired by the Robots universe.

Kellogg’s Pop-Tarts Presents Rescue the Rusties: A Breakfast-Fueled Time Capsule of Mid-2000s Advergaming

Introduction: More Than Just a Freebie in the Cereal Aisle

To dismiss Kellogg’s Pop-Tarts Presents Rescue the Rusties as merely a cynical piece of promotional fluff would be to miss its profound, if accidental, historical significance. Released in 2005 and distributed within specially-marked boxes of Pop-Tarts, this Windows CD-ROM is not a singular game but a fragmented triptych—a trifecta of mini-games bundled with behind-the-scenes videos and printable activities—all designed to capitalize on the marketing whirlwind surrounding the animated film Robots. Yet, within its cheaply pressed disc lies a meticulously preserved artifact of a specific moment in gaming and media convergence. It represents the apex of a late-90s/early-2000s trend where consumer packaged goods (CPG) giants like Kellogg’s, in partnership with studios and publishers like Vivendi Universal, created simple, branded digital experiences to drive box sales and film synergy. This review will argue that Rescue the Rusties, for all its technical limitations and narrative vacuity, is a critical case study in the lifecycle of advergames: a product of constrained development, defined by its target demographic, celebrated in its immediate commercial context, and ultimately preserved not by its publisher but by a community of archivists and nostalgic collectors. It is a game that lived and died by its business model, its legacy now existing in the liminal space between forgotten marketing material and curious relic of digital ephemera.

Development History & Context: The Vivendi-Kellogg’s Symbiosis

The game’s genesis must be understood within the volatile media landscape of 2005. The film Robots, produced by Blue Sky Studios and distributed by 20th Century Fox, was a mid-tier animated feature. To maximize profitability, its promotional strategy was expansive and cross-platform, extending far beyond traditional trailers and tie-in toys. Enter Vivendi Universal Games, then a powerhouse of licensed and casual titles (having absorbed Sierra and owned the Crash Bandicoot and Spyro franchises), which saw an opportunity in the CPG aisle.

Kellogg’s, seeking to leverage the family-friendly appeal of a robot-themed film for its Pop-Tarts brand—a product already associated with child-centric marketing—commissioned a simple, Windows-based CD-ROM. The development was almost certainly outsourced to a small, low-budget studio or internal Vivendi team specializing in “value” titles. The technological constraints are evident: the game uses a fixed/flip-screen visual style, top-down and side-view perspectives common in early 2000s casual and children’s software (e.g., Freddi Fish, Pajama Sam), and tile-matching and maze navigation mechanics that were computationally inexpensive and easy to implement. The “Robots” license provided the aesthetic skin—character designs, color palettes of metallic blues and grays—while the “Pop-Tarts” brand integration was literal, with the pastry’s logo appearing as a collectible in the main game. This dual-licensing structure defines its DNA: it is a Robots game only insofar as it borrows a setting and character types (Rusties, “bad robots”), and a Pop-Tarts game only in its most blatant in-game product placement. The game’s very title, with its clunky possessive “Kellogg’s Pop-Tarts Presents…”, is a direct artifact of this corporate symbiosis, a naming convention more common to Saturday morning cartoon sponsorships than to video games.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Story Told Through Mechanics and Icons

Rescue the Rusties possesses a narrative only in the most skeletal, asymptotic sense. There is no protagonist with a name or a voice. The “plot” is summarized in a single introductory screen or perhaps a brief text pop-up: “Malicious robots have captured the innocent Rusties! Squirt oil to disable them and rescue your friends!” This is not a story; it is a game instruction manual’s premise. The Rusties themselves—small, round, cheerful robots—are purely narrative tokens, objects of rescue with no agency, dialogue, or characterization. The antagonistic robots are simply “bad,” defined solely by their hostile patrol patterns.

This narrative vacuum is, in itself, thematically revealing. It reflects a design philosophy utterly subservient to brand safety and simplicity. There is no room for moral ambiguity, complex motivations, or even a traditional hero’s journey. The theme is pure, unadulterated altruism: rescue the helpless. The inclusion of the Pop-Tarts logo as a secondary collectible item further muddies any narrative coherence, introducing a piece of breakfast cereal into a robot rescue mission without explanation, purely as a branding exercise. The other two activities—Pick-A-Part and Bot Factory—are narratively null. Pick-A-Part frames its match-3 puzzle through the visual of a robot trying to steal gears, but this is a mechanical metaphor, not a story. Bot Factory offers the most potent, if brief, thematic thrust: the player becomes a “robot engineer,” a creator. In an act of pure, unlicensed imagination, you assemble, paint, and name your own robot. For a moment, the game shifts from a licensed Robots experience to a sandbox of personal creation, subtly echoing the film’s own theme of Rodney Copperbottom’s inventiveness. This three-second creative interlude is the deepest narrative layer the game possesses: you are not just rescuing a pre-existing world; you can briefly participate in its construction.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Trio of Disposable Delights

The game’s structure is a deliberate buffet of simple, discrete mechanics, each designed for short, satisfying play sessions—the “breakfast gaming” demographic.

1. Rescue The Rusties: This is the marquee mode, a top-down maze navigation puzzle. The core loop is: enter maze -> locate Rusty/collectible -> avoid/sabotage enemy robots via oil-squirting (a timed area-denial tool) -> return Rusty to exit. The oil mechanic is the sole strategic element, requiring the player to anticipate enemy patrol routes and create temporary safe passages. The mazes increase in complexity primarily through density of walls and number of enemy robots, not through new mechanics. It is essentially a simplified, action-oriented take on Capture the Flag or Knight Lore-style maze games, with stealth/disable mechanics replacing combat. The fixed-screen design means each level is a self-contained puzzle box, a common trope in children’s edutainment of the era.

2. Pick-A-Part: A direct, unmodified match-3 puzzle, a genre exploding in popularity post-Zuma and Bejeweled. The innovation, if it can be called that, is the “thief” mechanic: a conveyor of gears held by a magnet descends slowly. If gears reach a certain point, a robot mouth “steals” them, likely resulting in a loss condition. This adds a constant, visual pressure timer to the standard match-3 formula. The player must match gears to clear them and reverse the descent, creating a tension between careful pattern-building and the urgent need to prevent the line from dropping too low. It’s a competent, if derivative, implementation of the genre, with difficulty scaling through faster descent speeds and more complex gear arrangements.

3. Bot Factory: A pure character creator. With a selection of predefined parts (heads, bodies, arms, legs) and a basic paint tool (solid color fills only), the player assembles a robot. The system is not integrated into the other games; creations are static portraits saved to the disc. Its value is purely in the brief moment of creative agency, a stark contrast to the reactive gameplay of the other modes. It’s a digital sticker book with a robot theme.

Systems Analysis: The game lacks a unified meta-game or progression system. There is no currency, no persistent unlocks, and no linking between the three activities. Each exists in its own silo. The UI is straightforward, relying on clear icons and mouse-driven interaction. The difficulty curve is gentle but present, particularly in Rescue the Rusties‘ later mazes and Pick-A-Part‘s higher speeds. The design philosophy is clearly “accessible variety,” offering three distinctly different experiences (action-puzzle, casual puzzle, creativity) to appeal to a broad child audience with varying attention spans. There is no depth, no replay value beyond completionism, and no challenge for an experienced gamer. It is, in mechanical terms, a perfect reflection of its purpose: a disposable, brand-aligned distraction.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Shiny, sanitized Aesthetic of Corporate Synergy

The game’s visual and auditory presentation is its most direct link to the Robots film. It adopts the movie’s CGI-inspired, polished, plastic-looking art direction: everything is smooth, brightly colored, and devoid of texture grit. The Rusties are adorable, minimalist spheres with eyes and limbs, while the “bad robots” are angular, darkly colored, and move with a jerky, aggressive animation. The mazes are sterile, metallic corridors with simple wall textures. The color palette is dominated by the film’s signature metallic blues, silvers, and grays, with the vibrant pink and orange of the Pop-Tarts logo providing jarring, yet deliberate, bursts of licensed brand color.

Graphically, it sits squarely in the low-to-mid-tier of 2005 PC capabilities. It uses 2D sprites against simple backgrounds, with basic particle effects for the oil-slick and gear-matching sparks. There is no parallax scrolling, no dynamic lighting, and no advanced shader effects. Its fidelity is closer to high-end children’s software from 1998 than to a contemporary Robots video game adaptation. This is not a failure of budget but a feature: the art is clean, readable, and uncluttered, perfectly suited for its young target audience on modest household PCs.

The sound design follows the same formula. The music is a handful of looping, upbeat, futuristic synth-pop tracks that are inoffensive and vaguely energetic. Sound effects are crisp and functional: a squelch for the oil, a clank for robot movement, a cheerful ding for rescuing a Rusty, a satisfying chunk for a gear match. There are no voice lines beyond perhaps a few sampled exclamations. The auditory experience is designed to be pleasant background noise, never intrusive or complex. The world feels not like a lived-in Robots metropolis, but a sanitized, playful abstraction of one, a theme park ride version of the film’s setting where the only stakes are the completion of a task.

Reception & Legacy: A Blip That Became a Archive

Contemporary Reception (2005): There is virtually no recorded critical reception from the time. It existed outside the traditional games press, reviewed neither in magazines nor on major websites. Its audience was children who found the CD in their breakfast box and their parents. Its “success” was measured not by Metacritic scores but by its ability to drive Pop-Tarts sales and maintain positive brand association for Robots. In that narrow metric, it achieved its goal: it was a functional, appealing free toy that extended the film’s presence into the home.

Long-Term Reputation & Influence: The game’s post-release life is a study in digital preservation and niche collectibility.

* On Industry Influence: It had none. It did not inspire mechanics, set trends, or enter the cultural lexicon. It is not cited in developer retrospectives or design post-mortems. It represents a dead-end branch of game design: the high-volume, low-cost, brand-specific advergame for a narrow demographic. Its legacy is as a data point in the history of corporate partnerships.

* As a Cultural Artifact: Its significance grows inversely with its commercial relevance. Today, it is a cherished, obscure relic. Its presence on the Internet Archive (in both US and Australian “LCMs bar” variants), on sites like My Abandonware, and its persistent, if low-priced, listings on eBay ($5-$20) reveal a dedicated, if small, community of archivists, retro gaming enthusiasts, and pop-culture completists. The fact that multiple regional versions exist (the US Pop-Tarts version, the Australian LCMs version) adds a layer of fascinating distribution minutiae.

* Academic & Curatorial Value: For scholars of advergames, children’s digital media, or the business of licensing, Rescue the Rusties is a perfect primary source. It demonstrates the aesthetic and mechanical commonplace of its genre. Its bundling with a physical consumer good (a food product) and its subsequent transition to digital preservation platforms like the Internet Archive charts the lifecycle of a disposable digital object. It is a exhibit-quality example of “breakfast gaming.”

Conclusion: Verdict on a Promotional Ghost

Kellogg’s Pop-Tarts Presents Rescue the Rusties is not a good game by any conventional critical measure. It is shallow, repetitive, narratively barren, and technically rudimentary. Its creative output, the Bot Factory, is a tantalizing but ultimately isolated fragment of player expression. Yet, to judge it solely on these grounds is to critique a hammer for not being a screwdriver. Its value is not in its artistry or innovation but in its perfect, unadulterated embodiment of its context.

It is a flawless execution of a very specific, commercially-driven mandate: to create a set of simple, brand-safe, mechanically sound mini-games that would delight a child for 20 minutes and associate the Robots film and Pop-Tarts with that fleeting joy. In that, it succeeds. As a historical document, it is invaluable. It stands as a crisp, clear fossil of the mid-2000s advergame boom, a period when the barrier to entry for digital experiences was low enough for a cereal box to become a distribution platform. Its obscurity is its authenticity; it was never meant to be remembered, which makes its preservation all the more poignant.

In the grand canon of video game history, Rescue the Rusties occupies a minuscule, footnote-like position. But in the shadowy, fascinating archive of promotional ephemera, it is a cornerstone. It reminds us that the history of gaming is not just written in the AAA blockbusters and indie darlings, but also in the cheap, cheerful, and profoundly forgettable software that came free with your breakfast. Its final, ironic victory is that, while the Robots film is largely forgotten and Pop-Tarts boxes are discarded, this little CD-ROM, saved by strangers on the internet, endures. That alone secures its place not as a classic, but as a perfect specimen.