- Release Year: 2021

- Platforms: Macintosh, PlayStation 5, Windows

- Publisher: Epic Games, Inc.

- Developer: Arbitrarily Good Productions LLC, Namethemachine, LLC

- Genre: Simulation

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Music, rhythm

- Average Score: 100/100

Description

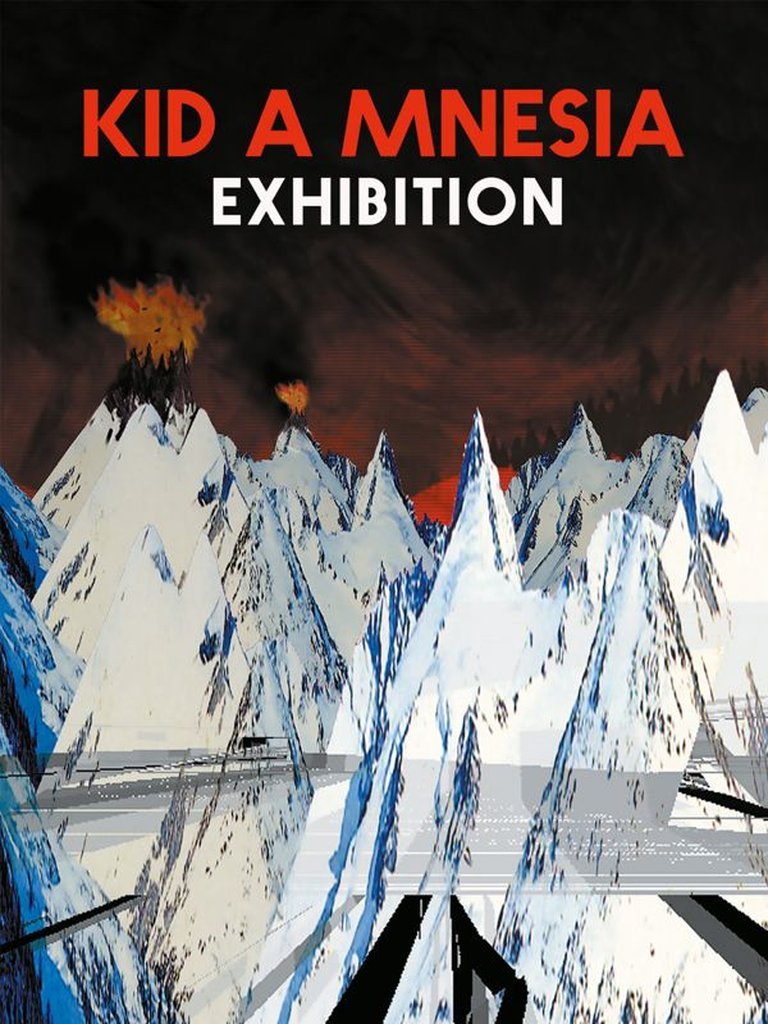

Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition is a 2021 walking simulator developed in collaboration with Radiohead’s Thom Yorke, Nigel Godrich, and Stanley Donwood, serving as a digital exhibition for the albums Kid A and Amnesiac. Players freely explore an abstract, brutalist virtual museum featuring immersive artwork and music from the albums, with no enemies, scores, or objectives, emphasizing an atmospheric audio-visual journey.

Gameplay Videos

Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (100/100): This is an amazing game, make sure you go inside the pyramid, that’s the best adventure.

visualfoodie.com : It is a living, breathing museum dedicated to a feeling.

eurogamer.net : Radiohead’s near-genreless music is paired with a remarkable first-person walkthrough that’s just a touch light on interactivity.

howlongtobeat.com (100/100): one of the most immersive musical experiences I’ve had.

Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition: Review

Introduction: The Architecture of Anxiety, Made Playable

In the landscape of video games, where interactivity is traditionally measured in conflict, progression, and mastery, Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition stands as a monumental, defiant anomaly. It is not a game in the conventional sense; it is an interactive manifestation—a digital reliquary built from the sonic rubble and visual anxieties of Radiohead’s two most fractured, futurist masterpieces, Kid A (2000) and Amnesiac (2001). Released for free in November 2021 to commemorate the albums’ 21st anniversary, this collaboration between the band, artist Stanley Donwood, producer Nigel Godrich, and studios Namethemachine and Arbitrarily Good Productions (with publishing might from Epic Games) is less something to be played and more something to be inhabited. It is a space where the unit of measurement is not experience points, but emotional resonance; where the primary mechanic is contemplation. My thesis is this: Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition represents a watershed moment for the walking simulator and a bold, successful experiment in transmedial art. It transcends its categorization as a “game” to become a definitive, playful, and profoundly unsettling museum for the digital age, proving that video game engines can be wielded not for escapist fantasy, but for immersive, abstract critique. Its legacy is twofold: it forever alters how we can engage with a music album, and it validates the walking simulator as a legitimate vessel for high-concept, auteur-driven art.

Development History & Context: From Brutalist Spacecraft to Virtual Ruin

The story of Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition is itself a tale of artistic adaptation in the face of global crisis, deeply rooted in the specific tensions of its time.

Origins and Vision: The project was conceived not by game designers, but by the core Radiohead creative triad: singer Thom Yorke, visual artist Stanley Donwood, and producer Nigel Godrich. Their initial vision, as documented on the PlayStation Blog and in Wikipedia, was audaciously physical. They imagined a vast, red, welded-steel structure—a “brutalist spacecraft” that had “crashed-landed into the classical architecture” of a city like London, inserted “like an ice pick into Trotsky.” This was to be a touring installation built from shipping containers, a monumental, site-specific “no rules” space mirroring the albums’ boundary-smashing ethos. The Victoria and Albert Museum was too small; the Royal Albert Hall was rejected by Westminster City Council. Even before the pandemic, logistical and permissions nightmares were threatening this dream.

Pandemic Pivot and Digital Liberation: The COVID-19 pandemic did not merely postpone this plan; it catalyzed a radical conceptual shift. With physical gatherings impossible, the team, collaborating remotely via Zoom over two years, embraced the virtual format. As Yorke and Donwood famously noted, their dream was “dead. Until we realised… It would be way better if it didn’t actually exist.” This pivot was not a compromise but a liberation. The digital medium freed the exhibition from “any normal rules of an exhibition. Or reality.” It could become an “upside-down digital/analogue universe,” a labyrinthine, impossible geometry that a physical structure could never contain. This context is crucial: the game’s unsettling, non-Euclidean architecture and its feeling of isolated, digital paranoia are direct artistic responses to the lockdown experience, transforming a canceled physical event into a globally accessible, introspective journey.

Tools and Team: Development was handled by the specialist studios Namethemachine (Matthew Davis) and Arbitrarily Good Productions (Sean Evans, Chelsea Hash), with critical creative input from theatre set designer Christine Jones. The team used Maya for asset modeling and Unreal Engine 4 for the complex, non-linear level design—a powerful choice that enabled the stunning, real-time rendering of abstract, shifting spaces. Wwise middleware was employed for the sophisticated spatial audio, allowing Nigel Godrich’s remixes to dynamically respond to player movement. The guiding principle was archivist purity: “no new work.” Every texture, sound, and sketch was sourced from the Kid A/Amnesiac era (1999-2001), pulled from original sketchbooks, lyric sheets, and multitrack recordings. The creative brief was “exploded songs”—deconstructing the final mixes and “laying them out” in 3D space.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story of a Feeling

There is no traditional narrative. There are no characters with arcs, no dialogue, no plot. Instead, Exhibition offers a profound, environmental thematic deep dive into the core psyche of the Kid A/Amnesiac era.

Core Themes as Architecture: The experience is a direct translation of the albums’ pre-millennial anxieties: technological alienation, political dread, informational overload, ecological collapse, and existential dissociation. You do not learn about these themes; you inhabit them. The opening black-and-white pencil forest is a literalization of the album artwork’s aesthetic and the music’s stark, barren emotional landscape. The towering, weeping minotaurs—recurring figures from Donwood’s art—represent bestial, trapped, sorrowful id. The endless stacks of buzzing CRT televisions (a visceral, anachronistic technology) evoke a media-saturated, glitch-ridden reality. The central, shifting pyramid is a monument to incomprehensible scale and divine, terrifying order.

Environmental Storytelling and “Exploded Songs”: The genius of the narrative lies in the spatial distribution of audio and visual fragments. Walking into a room might trigger an isolated, haunting vocal take from “How to Disappear Completely,” while a distant hallway might pulse with the distorted bassline of “The National Anthem.” This is not a soundtrack layered over the environment; it is the environment’s source code. The “Paper Chamber,” with its walls of fluttering, digitized sketchbook pages and lyric fragments, is a direct walkthrough of Donwood and Yorke’s creative process. The “Ghost Chamber” and other spaces are named after song titles, creating a loose, associative map. The most explicit narrative moment, praised by Eurogamer, is a corridor of fiery, wall-mounted lyrics from “Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors,” forcing the player to follow a fragmented text trail to progress—a literal enactment of being trapped in a recursive, textual maze.

The Player’s Role: Ghost, Not Hero: Thematic resonance is amplified by the player’s complete lack of agency in a traditional sense. You are a spectral observer, a “ghost in the machine.” This passive role mirrors the albums’ themes of powerlessness and observation (“I’m not here, this isn’t happening”). The experience forces a type of active receptivity. You are not conquering the space; you are being acted upon by it. The shift in perspective from protagonist to witness is the fundamental narrative mechanic.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Elegance of Constraint

To call Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition’s gameplay “minimalist” would be an understatement; it is purposefully, philosophically vacuous. This is its greatest strength and, for some, its primary flaw.

Core Loop and Interaction: The loop is simple: move (first-person, WASD/analog stick) and look. That is it. There is no jumping, no sprinting, no interaction button (outside of scripted sequences). Proximity triggers audio playback and occasional visual events (a TV turning on, a page fluttering). The environment is open but labyrinthine; there are no dead ends, and multiple paths weave between thematic rooms. The design intentionally provides no goals, no map, no HUD. The only “objective” is exploration itself.

Innovative System: Spatial Audio as Gameplay: The one truly innovative system is the implementation of proximity-based, layered spatial audio. Utilizing Godrich’s surround sound mixes and Wwise, music is not a global track but a geo-located entity. As you move, you hear different stems (vocals, strings, beats) emerge from specific architectural features—a pillar, a ceiling vent, a floating object. This turns exploration into an auditory scavenger hunt. You play the environment by moving to solve the “puzzle” of hearing the full composition. This system is the game’s heartbeat, making the player complicit in the reconstruction of the songs.

Flaws: The Cost of Passivity: The deliberate lack of agency can frustrate. As Eurogamer noted, the pace is “agonisingly slow” in scripted sequences where you cannot leave until a full track finishes. There are no skip functions. Some users on Metacritic and HowLongToBeat reported falling through geometry (“trap doors”) with no quick recovery, highlighting a lack of polish in collision and streaming. For an audience expecting even the modest interactivity of a Dear Esther or What Remains of Edith Finch, the total absence of puzzle-solving or meaningful object manipulation can feel like a missed opportunity to deepen engagement. However, these “flaws” are arguably intrinsic to the work’s philosophy: any added challenge would break the meditative spell.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Material of Memory

This is where the exhibition transcends its functional simplicity and achieves masterpiece status. The world is not a backdrop; it is the primary narrative and mechanical engine.

Visual Direction: Donwood’s Sketchbook, Built: Stanley Donwood’s iconic artwork—the stark mountains, the哭泣 minotaurs, the anxious stick figures—is not merely displayed but instantiated. The “Landscape Gallery,” based on a room in the Musée de l’Orangerie, transforms his 2D mountainscapes into vast, explorable dioramas. The “Pixel Warehouse” and “Televisions Room” create a glitchy, analog-digital hybrid aesthetic. The art style is raw, sketch-like, and intentionally “unfinished,” mirroring the creative moment of Kid A/Amnesiac. The color palette is deliberately muted (monochrome forests, concrete grays) punctuated by violent surges of red, blue, and yellow, guiding the eye and evoking the albums’ jarring dynamic shifts. The shift from the “physically plausible” early spaces to the “void-like, impossible” geometry of the central pyramid perfectly mirrors the musical journey from rock-based idioms to pure abstraction.

Sound Design: Godrich’s Spatial Remix: Nigel Godrich’s contribution is arguably the project’s most revolutionary aspect. He did not just place stereo tracks in the world; he re-engineered the multitracks for 3D space. The result is a living, breathing soundscape. A whispering vocal might be positioned directly beside your ear; a blaring brass section might circle overhead. Environmental sound (footsteps, wind, hums) is woven seamlessly with the musical stems. As The Verge’s Jay Peters observed, you don’t just hear “Everything in Its Right Place”; you walk through it, with its iconic keyboard riff occupying a physical corner of the room. This synesthetic integration—where sound defines space and space defines sound—is the exhibition’s ultimate technical and artistic achievement. It fosters a new way of listening, as The New Yorker noted, by making the listener complicit in the song’s architecture.

Atmosphere and Cohesion: The combination creates a uniquely oppressive yet beautiful atmosphere. It is “apocalyptic” (NME) yet filled with “pockets of beauty.” The feeling is one of melancholic awe, of being alone in a巨大, contemplative ruin built from your own cultural memories. The Unreal Engine 4 rendering allows for subtle, real-time lighting and particle effects (floating dust, flickering screens) that keep the world feeling alive and unstable. The sound design, often using lo-fi textures and analog hums, grounds the high-fidelity visuals in a tactile, “found” aesthetic.

Reception & Legacy: The Critical and Cultural Aftermath

Critical Reception: Upon release, Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition was met with widespread critical acclaim, particularly from non-gaming publications that valued its artistic ambition, and from gaming outlets that recognized its formal innovation. The New Yorker named it one of the best games of 2021, a significant accolade that legitimized its place in the medium. The Verge praised it as “a very literal expression of the idea that video games can be art.” NME highlighted its “untraditional, warped and magical” quality. The general consensus praised its perfect marriage of music and visual art, its immersive atmosphere, and its successful translation of the albums’ ethos into interactive space. Criticisms, as noted, centered on its limited interactivity and occasional technical hiccups (framerate drops, collision issues), with Gamereactor giving it a solid but cautious 7/10.

User Reception: User scores, particularly on Metacritic (8.3/10) and HowLongToBeat, are remarkably high and passionate. Reviews repeatedly echo key sentiments: the necessity of headphones, the importance of letting go of game-like expectations, and the transformative power of the pyramid sequence. Many users explicitly state it changed how they listen to the albums. The free price point is constantly cited as adding to the work’s generosity and impact. Negative user reviews often come from those expecting traditional gameplay or who simply dislike Radiohead’s aesthetic.

Industry and Cultural Legacy: The exhibition’s impact is already multifaceted:

1. Redefining Album-Companions: It set a new benchmark for what an album reissue can be. Instead of a deluxe box set with outtakes, it offered an experience. It directly influenced the approach to other artist-driven projects, proving that deep archival material can be recontextualized in 3D space.

2. Pushing the Walking Simulator Genre: It demonstrated the genre’s capacity for high-concept, auteur-driven projects that are non-linear, abstract, and philosophically rigorous. It sits alongside titles like The Stanley Parable and What Remains of Edith Finch as a peak of environmental storytelling, but with a musical core.

3. Expanding Unreal Engine’s Use Case: Epic Games’ involvement showcased UE4’s utility for non-violent, art-focused applications, encouraging other institutions and artists to consider game engines for virtual exhibitions and installations.

4. Academic and Museum Discourse: It has been cited in academic papers on digital media, synesthesia, and virtual museums. As noted in the sources, it directly contributed to the momentum for a physical retrospective of Donwood/Radiohead art at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (2025’s This Is What You Get). Furthermore, a physical version of the Exhibition itself is slated for Coachella’s Bunker stage in 2026, completing a fascinating circle from canceled physical dream to digital reality and back again.

5. The “Metaverse” Prototype: Long before Meta’s push, this project presented a compelling vision of a persistent, artistic, non-commercial digital space—a “fevered dream-space” that prioritizes aesthetic and emotional experience over socializing or commerce.

Conclusion: A Permanent Exhibit in the Gallery of the Mind

Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition is not merely a great “game” or a successful promotional tie-in. It is a landmark achievement in interactive art that fully justifies the use of the video game medium for non-interactive, contemplative ends. Its brilliance lies in its ruthless consistency of vision: every design decision, from the absence of a HUD to the spatialized audio, serves the core theme of deconstructing and rebuilding the emotional memory of two landmark albums. It is a work that demands a specific posture from the player—one of quiet openness—and rewards it with moments of profound, synesthetic beauty and unease.

It is flawed in its technical execution (the occasional collision glitch, the forced slow pacing), but these flaws feel almost appropriate, like glitches in the memory it attempts to simulate. Its legacy is secure. It expanded the vocabulary of what a video game can be, demonstrated the power of a major studio backing a pure art project, and created a permanent, explorable monument to one of rock music’s most daring creative periods. To step into its Brutalist pyramid, to hear “Pyramid Song” bleed from the very stones around you, is to understand that some feelings—anxiety, awe, melancholy, wonder—are best explored not through challenge, but through space and sound. Kid A Mnesia: Exhibition is the ultimate proof. It is not a game to be beaten, but a world to be remembered. It is, in the truest sense, a classic.