- Release Year: 1986

- Platforms: Arcade, BREW, DoJa, MSX, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, TurboGrafx-16, Wii, Windows

- Publisher: Hamster Corporation, MediaKite Distribution Inc., Taito America Corporation, Taito Corporation

- Developer: Taito Corporation

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Item collection, Platform, Power-ups, Shooter

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 51/100

Description

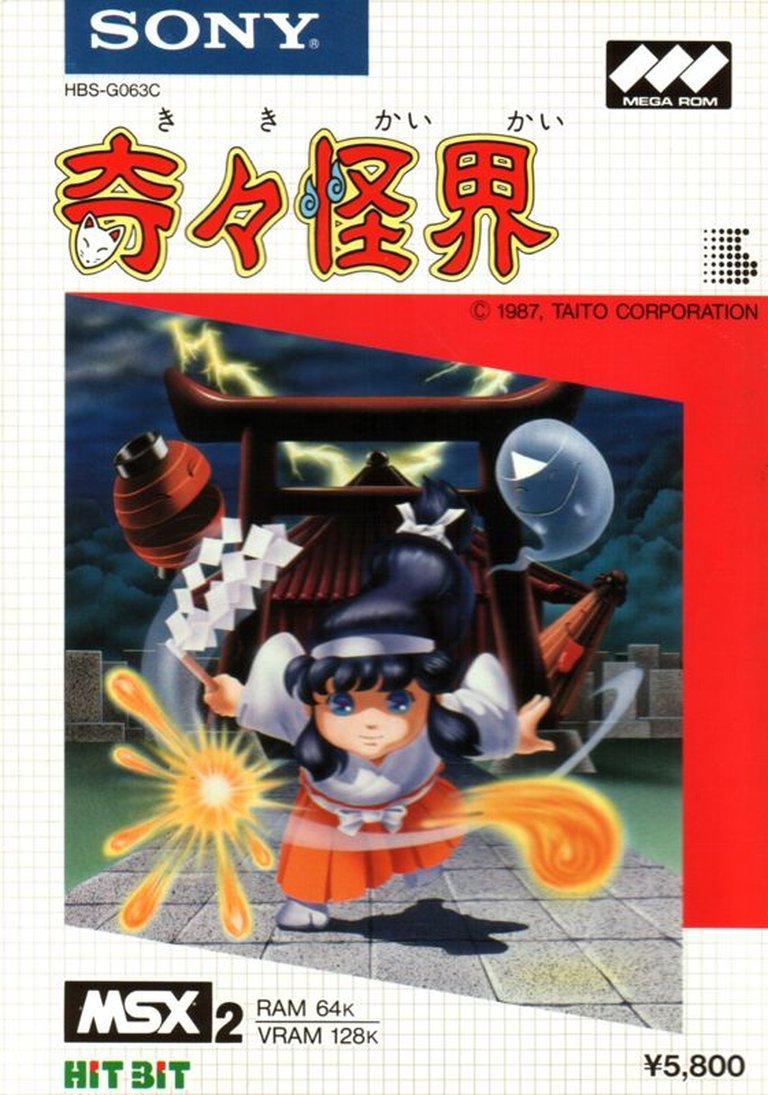

KiKi KaiKai is a fantasy action game where you play as a young girl tasked with rescuing her family from creatures of the underworld. Armed with magical scrolls, cards, and other weapons, you navigate through various scenes, defeating enemies and collecting runes to power up your abilities. Each level ends with a boss battle, and successfully completing a round frees a family member, bringing you one step closer to reuniting your family.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy KiKi KaiKai

PC

KiKi KaiKai Mods

KiKi KaiKai Guides & Walkthroughs

KiKi KaiKai Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (51/100): Average score: 51% (based on 5 ratings)

videogameden.com : Kiki Kaikai is a nice little game but I personally much prefer the Super Famicom versions that came later.

hardcoregaming101.net : Kiki Kaikai certainly wasn’t Taito’s first foray into run-and-guns or shoot-em-ups, but it stands out as their most unique take on those prevalent genres.

KiKi KaiKai Cheats & Codes

NEC PC Engine/Turbo Grafx 16

Codes are entered at the title screen.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| Hold I and press Up, Left, Down, Right, Up, Right, Down, Left. Release I, then hold Select and press II ten times. | Gives 9 lives |

| On the title screen, hold any button (besides a directional button) then hit Up, Down, Left, Right, Left, Right, Down | Unlocks sound test that has many sounds not heard in the game |

Arcade

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| After you get a Game Over, hold the joystick for the first player up. Insert a credit and start a new game. | Gives one additional life |

MSX

Codes are entered at the title screen.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| Hold 1 + 5 + 0 and press Space to start the game. | Gives powered up state and 10 lives |

KiKi KaiKai: A Shrine Maiden’s Haunting Legacy

Introduction

In the neon-saturated arcade landscape of 1986, where space marines and cybernetic ninjas dominated the screen, Taito unleashed a radical anomaly: KiKi KaiKai. This top-down shooter dared to replace lasers with Shinto talismans, aliens with yōkai, and chrome with cherry blossoms. Far more than a mere curiosity, its quaint exterior belied a sophisticated, folklore-infused action experience that birthed a beloved franchise yet remains one of Taito’s most enigmatic creations. Over three decades, KiKi KaiKai has transcended its modest origins to become a touchstone for Japanophilic design, a cautionary tale about localization, and an enduring influence on indie darlings like Touhou Project. This review dissects its genesis, mechanics, artistry, and contested legacy to argue why this “lovely action game” deserves deeper reverence than its niche reputation suggests.

Development History & Context

Emerging from Taito’s Kumagaya Laboratory, KiKi KaiKai was the brainchild of designer Hisaya Yabusaki, who sought to subvert the sci-fi orthodoxy of the era. Released in Japanese arcades in October 1986 and North America that December, it operated on Taito’s “FLTL2” hardware—a dual Zilog Z80 CPU (6MHz) setup paired with a Motorola M68705 for auxiliary tasks, soundtracked by a Yamaha YM2203 chip. This constrained environment demanded ingenious resource allocation, yet Yabusaki leveraged it to craft a “lovely action game” brimming with “exotic Asian atmosphere.” Its development coincided with a boom in vertical shooters, but while titles like Commando focused on military action, KiKi KaiKai drew inspiration from yōkai scrolls and folk tales. Director Mikio Hatano emphasized player agency, rejecting the forced-scrolling design of peers for free-roaming 8-directional movement—a radical choice that prioritized tactical depth over spectacle. The game’s modest commercial success (ranked #2 in Japan’s arcade charts for November 1986 and #10 for 1987) belied its cultural impact, though it was quickly bootlegged internationally as Knight Boy, preserving gameplay while rebranding it with a generic fantasy facade.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, KiKi KaiKai weaves a deceptively simple folktale: Sayo-chan, a young Shinto shrine maiden, is summoned by the Seven Lucky Gods (Daikokuten, Hotei, etc.) only to witness their abduction by mischievous yōkai. Her quest to rescue them becomes a pilgrimage through feudal Japan’s supernatural heartland. The narrative’s brilliance lies in its thematic economy. Sayo’s role as the “touched by luck” lone survivor mirrors the miko’s real-world function as a mediator between realms. Her journey is not merely a rescue mission but a reaffirmation of order against chaos, embodied by her dual weapons: the o-fuda talismans (consecrated paper for spiritual warfare) and gohei wand (a purifying ritual tool). Enemies like the lantern-wielding Chochin-obake or neck-stretching Rokurokubi are drawn directly from Edo-period legends, transforming gameplay into a living bestiary of Japanese folklore. Even the final boss—a doppelgänger of Manuke (a tanuki ally in later series)—echoes themes of deception and identity. Dialogue is minimal, yet Sayo’s determined silence and the gods’ silent imprisonment speak volumes about duty and sacrifice, creating a story richer in subtext than its pixelated aesthetic implies.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

KiKi KaiKai’s genius lies in marrying run-and-gun intensity with methodical strategy. Players control Sayo-chan across eight stages, fighting yōkai through two core mechanics:

– Projectile Combat: Throwing o-fuda talismans in eight directions, with power-ups (red for piercing, yellow for size, blue for extended range) collected from fallen enemies. Notably, blue o-fuda also inflate boss health, adding risk-reward calculus.

– Melee Defense: Swinging the gohei wand for close-quarters damage, though its limited arc and inability to harm bosses force tactical retreats.

The game’s standout innovation is player-controlled scrolling. Unlike fixed shooters, Sayo can advance or retreat, letting players herd enemies into kill zones or dodge volleys. This is balanced by punishing mechanics: slow movement speed, clinging Rumuru yōkai that immobilize her, and immortal Garakotsu zombies that accelerate if attacked while the player lingers. Boss battles are arena-based spectacles—like a fire-breathing Tengu or thunder-slinging Raijin—with the arena floor cracking as damage is dealt, eschewing health bars for visual feedback. The “number match” continue system, where free games are granted if a score’s last digits match a random number, adds a gambling-like tension. However, the arcade’s brutal difficulty (one-hit deaths, no continues) and monotonous stage design (repetitive enemy patterns) are persistent flaws, mitigated only in ports like the PC Engine’s branching paths or the Famicom Disk System’s added lives.

World-Building, Art & Sound

KiKi KaiKai’s world is a masterclass in cultural authenticity. Set against feudal backdrops—pagodas, torii gates, and bamboo forests—the stages are dioramas of Shinto-Buddhist cosmology. Art director Toshiyuki Nishimura’s character designs blend whimsy with horror: grinning Kasa-obake (umbrella ghosts) and skeletal Bake Uri (gourd demons) recall ukiyo-e woodcuts, while Sayo’s traditional attire (red hakama, white kimono) grounds the fantasy in tangible ritual. Even the bootleg Knight Boy retained these sprites, a testament to their enduring appeal.

Hisayoshi Ogura’s soundtrack elevates the atmosphere with shamisen melodies and koto-driven chiptunes, fused with electronic beats. The title theme’s jaunty rhythm mirrors Sayo’s pluck, while boss tracks swell with taiko drums, evoking Noh theatre tension. Sound effects—from the gohei’s woosh to yōkai shrieks—are sampled from real-world rituals, making combat feel spiritually resonant. This synergy of sight and sound creates an “eldritch” ambiance, transforming a shooter into a ghostly pilgrimage.

Reception & Legacy

KiKi KaiKai’s trajectory mirrors a folk tale itself. In 1986, it was a modest hit, but its legacy fractured across ports and cultures. The Famicom Disk System’s Dotou-hen (1987) introduced co-op (alternating play as Miki-chan) and new levels, yet the MSX2 port’s slowdown and PC Engine’s branching paths couldn’t salvage its niche appeal. Western critics were unforgiving: GameSpot dismissed it as a “sleepier” Taito title, while AllGame lamented its “dull” graphics after initial novelty. MobyGames’ paltry 51% critic score reflects this, though player ratings (3.2/5) hint at a cult following.

Yet its influence is undeniable. Taito’s 1992 licensing of Kiki KaiKai: Nazo no Kuro Mantle to Natsume birthed the Pocky & Rocky series, popularizing co-op yōkai brawlers. Even more profoundly, ZUN’s Touhou Project drew direct inspiration—Reimu Hakurei’s design and ghost enemies are spiritual descendants of Sayo-chan. References persist in Rainbow Islands’ secret stages and Bubble Symphony’s haunted worlds. A canceled Wii sequel, Kiki KaiKai 2, resurfaced as the unlicensed Heavenly Guardian, proving the concept’s vitality. Modern compilations like Taito Milestones 2 (2023) now celebrate it as a foundational “exotic” shooter, though its difficulty remains divisive.

Conclusion

KiKi KaiKai is a paradox: a flawed yet foundational gem whose brilliance is often overshadowed by its obscurity. Its gameplay innovations—player-controlled scrolling, folklore-driven design, and risk-reward power-ups—were ahead of their time, even if its execution was hampered by arcade-era constraints. Sayo-chan’s journey remains a poignant allegory for cultural preservation: a lone defender of tradition against supernatural chaos. While its legacy is fractured by port disparities and critical neglect, its DNA permeates modern indie games and otaku culture. As a historical artifact, it’s essential; as an experience, it’s demanding yet rewarding. In the pantheon of Taito’s classics, KiKi KaiKai may not have the star power of Bubble Bobble, but its haunting charm and enduring influence secure its place as a shrine maiden’s enduring legacy. Verdict: A Cult Classic Worth Exorcising.