- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Freeloader

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Puzzle elements

- Average Score: 55/100

Description

In the quirky arcade-puzzle game Krazy Bus, players take the wheel of a bus loaded with groups of three colored potatoes. The objective is to navigate through city streets blocked by stationary potatoes. To clear a path, the player must strategically release their own potatoes ahead of the bus; when a potato collides with another of the same color, both vanish. Hitting a different color causes them to stack, creating new obstacles. Bonus points are awarded for clearing potatoes positioned on special bonus platforms.

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

vgtimes.com (55/100): Quick rating

Krazy Bus: A Journey into Obscurity

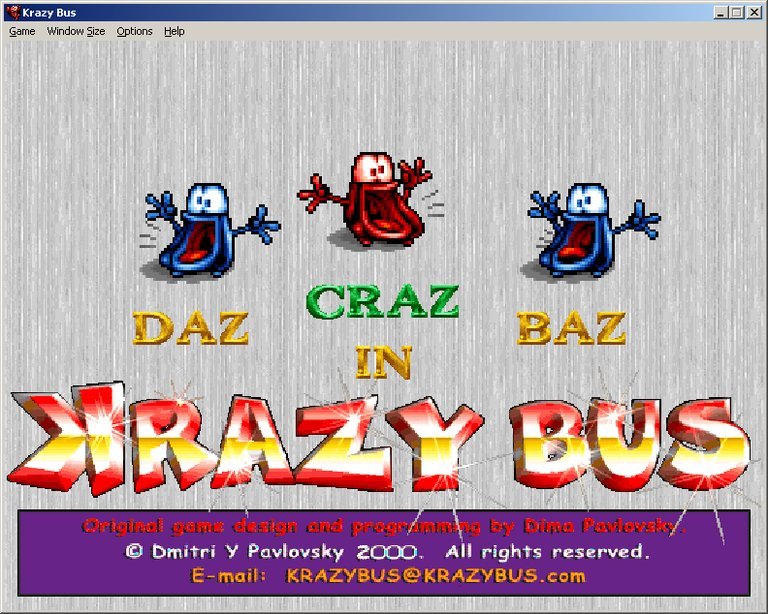

In the vast and often meticulously cataloged annals of video game history, there exist titles that defy conventional critique. They are not masterpieces to be celebrated, nor are they catastrophes to be universally derided. They are, instead, curious artifacts—footnotes in a digital library so immense that their very existence becomes a subject of fascination. Krazy Bus, a Windows title released in the year 2000 by the enigmatic publisher Freeloader, is one such artifact. It is a game that operates on a logic all its own, a top-down puzzle-action hybrid centered on the most unlikely of protagonists: a bus laden with sentient, colored potatoes. This review seeks to excavate Krazy Bus from its well-deserved obscurity, not to crown it a lost classic, but to understand its peculiar place in the gaming ecosystem of its time and the strange, almost defiantly minimalist design choices that define it.

Development History & Context

The Studio and The Vision

The development history of Krazy Bus is shrouded in a mystery as thick as the potato-clogged streets it depicts. The game’s developer remains officially “Unknown,” a fitting credit for a title that feels like it emerged fully formed from the ether of early internet shareware. The publisher, Freeloader, is itself a ghost in the machine, a name that suggests a certain ethos of casual, perhaps even frivolous, software distribution. This was the era just before digital storefronts streamlined distribution, a time when small, oddball games like this could appear on a download site like a strange fish washing up on a beach, with no explanation of its origin.

The vision, if one can call it that, appears to have been a starkly utilitarian one: create a simple, mechanics-driven experience with a singular, bizarre hook. There is no evidence of a large team or lofty ambitions. Instead, Krazy Bus feels like the product of a lone developer or a very small group experimenting with a core concept, wrapping it in the most basic visual presentation possible, and releasing it into the wild. The technological constraints were likely self-imposed; the game supports only a windowed mode, indicating a project built for simplicity and ease of access rather than pushing hardware boundaries. In the year 2000, when games like Deus Ex and The Sims were demonstrating narrative and systemic complexity, Krazy Bus stood as a stark, almost anachronistic counterpoint—a reminder of the bare-bones arcade experiences of a decade prior.

The Gaming Landscape of 2000

The release of Krazy Bus coincided with a pivotal moment in PC gaming. The industry was rapidly commercializing, with budgets swelling and genres solidifying. Into this landscape, Krazy Bus arrived not as a competitor, but as a peculiar sideshow. It belonged to a class of software that was becoming increasingly marginalized: the small-scale, digitally distributed oddity. It had more in common with the freeware and shareware scenes of the early ’90s than with the retail titles of its own day. Its existence is a testament to the fact that even as the industry marched toward a blockbuster future, there was still room for the inexplicable and the niche.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Plot and Characters

To analyze the narrative of Krazy Bus is to confront a profound void. There is no plot. There are no characters in any traditional sense. There is only a premise, delivered with the cold clarity of a technical manual: “The player must steer a bus with groups of three colored potatoes on it.”

The bus itself is a mere vessel, an abstract rectangle granted the power of movement. The potatoes are not individualized; they are commodities defined solely by their hue—red, green, blue, or others. They possess no agency, no dialogue, no backstory. They simply are. They stand in the road, and they must be dealt with. The game’s world is one of pure function, utterly devoid of context. Why is the bus transporting potatoes? Why are other potatoes blocking the road? Why do matching colors cause annihilation? These questions are not only unanswered but are rendered completely irrelevant by the game’s design. The narrative is the mechanics.

Underlying Themes

In this absence of story, one might be tempted to project meaning. Is Krazy Bus a bleak allegory for resource management under late capitalism? A commentary on the homogenization of society, where difference is punished (stacking) and conformity is rewarded (disappearance)? Such readings, while entertaining, are undoubtedly generous. The game’s primary theme is one of process. It is about solving a logistical problem with efficiency. The only narrative arc is the player’s own growing understanding of the system. The tension arises not from a emotional climax but from the escalating complexity of the potato-based obstacles. It is a game that celebrates pure, unadulterated game-ness.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Core Loop

The genius, such as it is, of Krazy Bus lies in the stark simplicity and frustrating potential of its core gameplay loop. The player controls a bus from a top-down perspective, navigating a grid-like network of streets. The bus is pre-loaded with groups of three colored potatoes.

The primary objective: Navigate the bus through the streets to… an unspecified destination. The goal is simply to progress, likely until a timer expires or a specific score is reached.

The primary obstacle: The streets are barricaded by stationary potatoes of various colors.

The primary tool: The player can release a group of their potatoes from the front of the bus. These released potatoes will travel in a straight line down the street ahead.

- If a released potato collides with a stationary potato of the same color: Both potatoes vanish, clearing a path.

- If a released potato collides with a stationary potato of a different color: They “stack.” This does not clear the path and instead creates a new, compounded obstruction, making future navigation more difficult.

This creates a tense puzzle-action dynamic. The player must constantly make strategic decisions:

* Which color to deploy? Assessing the road ahead to use a color that will clear the maximum number of obstacles.

* When to deploy? Timing is crucial, as a misjudged release can stack potatoes directly in your intended path, creating a dead end.

* Positioning the bus. Steering the bus to align with the optimal street for a potato launch is a key part of the arcade skill.

Bonus Systems and Progression

The game features a slight wrinkle in its otherwise minimalist design: “Some potatoes stand on bonus platforms – clearing the potatoes standing on the platform gives the player bonus points.”

This introduces a secondary objective. Do you clear a path of least resistance, or do you risk maneuvering the bus to aim for these bonus platforms to maximize your score? This tiny system is the closest the game comes to strategic depth, asking the player to weigh risk against reward.

There is no character progression, no unlockables, and no discernible change in mechanics from level to level. The progression is one of pure difficulty—the layouts become more complex, and the density of potato obstacles increases. The UI is undoubtedly as minimal as the rest of the game, likely consisting only of a score counter and perhaps a timer or level indicator.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Direction and Atmosphere

The visual presentation of Krazy Bus, based on its description and era, can be reliably imagined. It almost certainly utilizes a rudimentary 2D top-down perspective, reminiscent of early arcade games or the simplest of RPG makers. The world is a flat plane of streets, likely a dull gray, against a plain background. The bus is a simple sprite, a rectangle on wheels. The potatoes are likely just colored circles or ovals.

This is not a world built for immersion; it is a world built for clarity. Every visual element serves a purely functional purpose. The color coding of the potatoes is the most important visual cue. There is no texture, no detail, no animation beyond basic movement. The atmosphere is one of stark utilitarianism. It feels less like a living world and more like a whiteboard diagram for a game concept that was never fleshed out. This aesthetic, whether born from limitation or intent, contributes massively to the game’s unique, almost alienating identity.

Sound Design

No information exists on the sound design, but it is safe to assume it matches the visuals. Expect simple, repetitive bleeps and bloops for actions: a sound for releasing potatoes, a slightly more satisfying “pop” or “zing” for a successful color match and disappearance, and perhaps a jarring “thud” for a failed match and stack. Music, if present, would be a generic, forgettable MIDI loop. The sound, like everything else, would be designed to provide audio feedback for the mechanics and nothing more.

Reception & Legacy

Critical and Commercial Reception

The most telling data point regarding Krazy Bus‘s reception is its absence thereof. On MobyGames, a site renowned for its exhaustive cataloging, there are zero critic reviews and zero player reviews. It has been “collected by” only 3 users on the platform. It was a non-event in the gaming world. It garnered no press, no previews, and no post-release analysis. It was not commercially successful because it likely had no commercial presence to speak of; it was the definition of a obscure, downloadable curiosity.

Its ratings on other sites, like VGTimes, appear to be placeholder scores (5.5 across the board) generated by a site’s rating system that has never actually been engaged by a real user. The game exists in a state of critical purgatory—not panned, but simply ignored.

Evolution of Reputation and Influence

Krazy Bus has no reputation to evolve. It possesses no “so bad it’s good” cult following like Big Rigs: Over the Racing or Ride to Hell: Retribution. Its legacy is one of pure obscurity. It is a fossil, perfectly preserved in digital amber, that tells a very specific story: the story of games that barely were.

Its influence on subsequent games is non-existent. However, its existence is historically significant as a perfect example of the sheer volume and variety of software produced during the dawn of the digital distribution age. It represents the lower bound of game development—a title that implements a single idea with the absolute minimum of resources and presentation. It is a fascinating case study in how a game can be stripped down to its bare mechanical essentials, for better or worse.

Conclusion

Krazy Bus is not a good game. Nor is it a traditionally bad one. It is an elemental game. It is a game reduced to its most fundamental components: a player input, a rule set, and a feedback loop. It is a clinical, almost anthropological study of game design in its rawest form, completely unadorned by narrative, artistic ambition, or commercial intent.

To play Krazy Bus today is not an act of entertainment but an act of historical excavation. It is a window into a forgotten corner of gaming’s past where a lone developer could create a game about a bus and its potato-based logistics problems and release it to a world that would never notice. It is, in its own utterly inexplicable way, a perfect artifact. It serves as a reminder that the video game landscape is built not just on mountains of legendary triumphs and infamous failures, but also on a vast, flat plain of quiet, peculiar, and ultimately forgotten curiosities like Krazy Bus. Its place in history is secure: as a definitive, albeit minor, answer to the question, “What is a video game?” Its answer: at its most basic, it can be anything. Even this.