- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ValuSoft, Inc.

- Developer: Antidote Entertainment

- Genre: Gambling

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Cards, Tiles

- Setting: Contemporary, Las Vegas

- Average Score: 0/100

Description

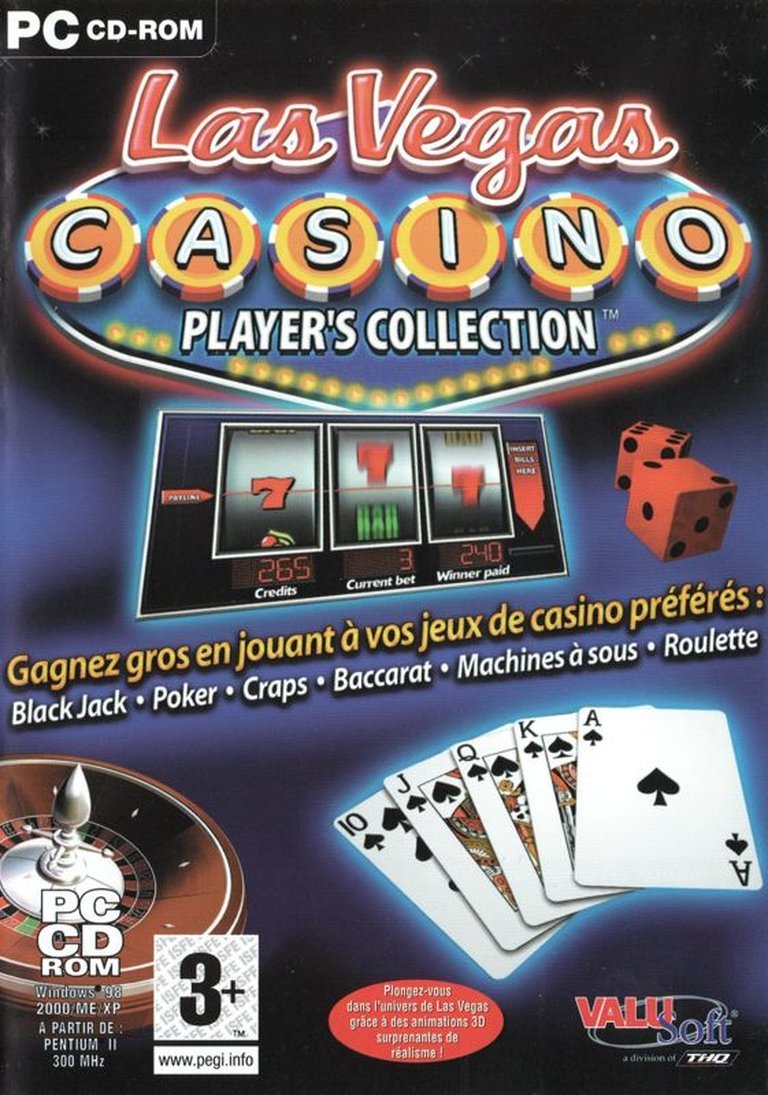

Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection is a 2003 Windows gambling simulation set in a contemporary Las Vegas casino environment. It features 3D animations and offers six classic casino games—including Blackjack, Poker, Craps, Baccarat, Slots (with three machines), and Roulette—each with multiple betting levels for an immersive gaming experience.

Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection Free Download

Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection Reviews & Reception

myabandonware.com (0/100): Very advocate for playing while in vacation.

Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection: A Dusty Chip on the Timeline of Gambling Simulators

Introduction: The High-Stakes Low-Profile of a Budget Compilation

In the vast, neon-dotted landscape of video game history, certain titles gleam with the polish of critical acclaim or industrial impact, while others reside in the quieter, seedier corners of the digital casino—forgotten, functional, and emblematic of a specific, unglamorous niche. Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection is firmly, proudly, one of the latter. Released in 2003 for Windows by the prolific budget-publisher ValuSoft and developed by the small studio Antidote Entertainment, this compilation is not a game that sought to revolutionize its genre. Instead, it existed as a straightforward, no-frills product for a specific market: the PC owner in the early 2000s who wanted a quick, accessible taste of casino table games and slots without leaving their desktop. This review will argue that Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection is a significant historical artifact precisely because of its conventionality. It serves as a perfect capsule of the early-2000s casual and “pick-up-and-play” compilation market, reflecting the technological constraints, business strategies, and muted ambitions of its time. It is less a game to be judged by its artistic merits and more a document of a perpetually running economic model in software: the low-cost, high-volume compilation aimed at a demographic often overlooked by the industry’s creative elite.

Development History & Context: ValuSoft, Antidote, and the Gold Rush of the Bargain Bin

To understand Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection, one must first understand its corporate progenitor: ValuSoft. Operating from 1997 until its shuttering in 2010, ValuSoft carved out a lucrative niche as a publisher of “value-priced” software, primarily for the Windows platform. Their business model was not about blockbuster status but about shelf presence in big-box retailers like Walmart and Best Buy, where titles priced at $9.99-$19.99 could sell in quantities that made slim margins profitable. They specialized in compilations, educational software, and licensed games of middling quality, targeting an audience of casual players, families, and seniors.

Antidote Entertainment, the developer credited on this title (with a core team of ten led by Lead Programmer Renaud Richard and Lead Artist Jesse Dubberke), was a small studio that frequently collaborated with ValuSoft. A perusal of their credits on MobyGames reveals a pattern of work on budget titles across disparate genres: the studio also contributed to Ultimate Pinball (another compilation), children’s games like VeggieTales: Minnesota Cuke and the Coconut Apes, and hidden-object adventures such as White Haven Mysteries. This is the profile of a “work-for-hire” studio, adept at delivering functional products on tight deadlines and budgets for a publisher with a specific retail vision. The technological constraints were those of the mainstream PC in 2003: Windows 98/ME/XP, 3D acceleration becoming standard but not yet demanding, and an expectation of simple point-and-click interfaces.

The gaming landscape of early 2003 was a fascinating dichotomy. On one hand, the era was defined by the looming launch of the Xbox (2001) and GameCube (2001), and the PlayStation 2’s dominance, pushing increasingly cinematic and complex 3D experiences. On the other, the PC casual market was booming in a different direction. The success of PopCap’s Bejeweled (2001) and the nascent social game space (pre-Facebook) pointed to demand for simple, repeatable play sessions. Furthermore, the casino/ gambling simulator genre was a perennial, if critically ignored, staple on PC, with predecessors like Las Vegas Super Casino (1995, 1997) and Vegas Stakes (1993 for SNES) having established a basic template. Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection entered this space not to innovate but to consolidate and modernize the “bargain bin casino” experience with contemporary (for 2003) “vivid 3D animations,” as the IGN summary hyped.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The absence of story as the story

As a pure gambling compilation, Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection possesses a narrative structure so skeletal it borders on the avant-garde. There is no plot, no characters, no dialogue, and no overarching theme beyond the most literal: simulating casino games. The “setting” is simply “Contemporary” and “City – Las Vegas,” as cataloged on MobyGames.

However, a deeper thematic analysis can be applied to its structural narrative. The game presents a fantasy of pure, consequence-free economic agency. Upon launching, the player is “in” a casino, but the framing is minimal—likely a reception area from which to select games. The player creates an “account” (a save slot) and is immediately given $1,000 in virtual currency. There is no backstory, no reason for being there, no house character to interact with (the lone credit for “Voices” granted to Paul Firlotte suggests minimal, likely menu-based, vocal feedback). This is the narrative of the slot machine itself: a self-contained loop of risk and reward, stripped of all social, emotional, or moral context. The theme is pure instrumental rationality. The game’s only “story” is the one the player writes in their own rising and falling chip stack, a private drama of mathematics and luck played out in a simulated, sanitized Vegas. It reflects a specific cultural moment where digital gambling was being divorced from its seedy, narrative-rich associations (from the gangsters of Casino to the high-stakes drama of Rounders) and repackaged as a neutral, solitary, and endlessly repeatable utility. The game is less a narrative and more a systemic sandbox; its theme is the banishment of story in favor of procedural gameplay, a hallmark of the casual and simulation markets.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Functionality Over Flair

The core gameplay loop is as straightforward as the concept: select a game, place a bet within defined limits, engage with the rules, and receive a payout based on the outcome. The compilation includes six discrete gambling activities, each with its own internal logic and “multiple levels of betting,” as the official description states.

- Blackjack: The classic card game. The description mentions “doubling-down, splits and a chance to buy insurance,” indicating a competent implementation of standard rule variations. The gameplay would be a first-person perspective against a virtual dealer, using a point-and-click interface to hit, stand, double, or split.

- Poker: This is the most ambiguous entry. The term “Poker” in a casual casino compilation circa 2003 most likely refers to a simplified version of video poker (like “Jacks or Better”) rather than a full Texas Hold’em simulator against AI opponents. The IGN blurb mentions “Jokers Wild,” a strong indicator of a video poker variant where the Joker acts as a wild card. This suggests a single-player, machine-based poker experience focused on constructing the highest-ranked hand from a dealt set of cards, with the option to discard and draw.

- Craps: The dice game. Implementation would require a 3D animation of dice being thrown and a clear overlay for betting on the pass line, come, don’t pass, etc. For a budget title, the betting options were likely pared down to the most common bets.

- Baccarat: The elegant, simple card game where bets are placed on the “Player” or “Banker” hand, with the closest to 9 winning. Its inclusion points to an attempt at offering a more “sophisticated” table game.

- Slots (Three different machines): The only explicitly varied sub-category. Three distinct slot machine simulations would each have different reel symbols, paylines, and likely a unique bonus round or “progressive jackpot” feature, as touted in the IGN summary.

- Roulette: The wheel-based game of chance. Players would choose numbers, colors, or groups, with the ball’s landing spot determining wins.

Systems & Interface:

* Interface: “Point and select” is the specified input method. The entire game is designed for mouse-driven navigation, with menus for game selection, betting, and in-game choices. This aligns perfectly with the casual PC user.

* Progression: There is no character progression or RPG-like system. The only “progression” is the accumulation (or loss) of the starting $1,000 bankroll. The game tracks this balance persistently within a save file/account.

* Innovation/Flaws: There is no evidence of innovation. The game’s likely “flaw” was its sheer simplicity—it offered no hook beyond the games themselves. There was no career mode, no tournament structure, no AI with personality, no custom rulesets, and no online multiplayer (an era when dial-up was still common and not assumed for such titles). It was a digital replication of physical games, valued for convenience and low cost. The “3D animations” were a selling point against 2D predecessors, but would have been rudimentary by contemporary AAA standards.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Generic Glimmer of Vegas

The game’s world is its most defined aspect: a simulation of a Las Vegas casino floor. However, the sources provide almost no concrete details about its artistic execution. We must infer from the era, the platform, and the budget.

- Visual Direction: The “Fixed / flip-screen” perspective suggests a static or slowly panning camera for each game table/slot machine, possibly with a static background that attempts to evoke a casino environment—chandeliers, carpet patterns, felt tables. The “vivid 3D animations” promised in marketing would have been applied to the core action: the dealing of cards, the spinning of the roulette wheel, the rolling of craps dice, and the spinning of slot reels. These animations would have been the game’s graphical highlight—smooth but likely using low-polygon models and simple textures to run acceptably on mid-range PCs of the time. The overall aesthetic would have been one of generic, corporate-friendly “Vegas” glamour: gold trim, red velvet, flashing lights—a sanitized, family-friendly version of the real thing, consistent with its PEGI 3 / ESRB E rating.

- Sound Design: The credits list “Sounds” to Jesse Dallon and Jesse Dubberke, and “Voices” to Paul Firlotte. Sound design would consist of:

- Ambient Loop: A low, repeating track of generic casino noise—chatter, distant slot jingles, maybe a muffled band.

- Game SFX: The clack of chips, the shuffle of cards, the rattle of dice, the ring of roulette ball on the wheel, the celebratory (or disappointing) chimes of slot machines.

- Voice: Paul Firlotte’s contribution was likely limited to short, synthesized phrases for game events: “Winner!”, “Blackjack!”, “Seven out!”, delivered in a smooth, non-committal dealer’s tone.

- Music: No specific composer is listed, suggesting either library music, a very simple original track, or no at-all music beyond ambient loops, which was common for low-budget compilations.

- Atmosphere Contribution: The art and sound worked in concert to create an atmosphere of accessible, risk-free仿真 (simulation). The visuals were bright and clear to ensure readability of game states. The sound provided auditory feedback crucial for gameplay (e.g., hearing the dice roll) but avoided the immersive, potentially overwhelming or sinister atmosphere of a real casino. The goal was functional ambiance, not artistic statement.

Reception & Legacy: The Sound of Silence

The critical and commercial reception of Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection is a study in profound, resounding silence. The source material is unequivocal:

- Critical Reviews: On MobyGames, the page explicitly states: “Be the first to add a critic review for this title!” Metacritic lists the game but shows “Critic Reviews” as unavailable. IGN and GameSpy have mere placeholder pages with no review text, only basic summaries and specs.

- User Reviews: Metacritic’s user review section for the PC version states: “User reviews are not available for Las Vegas Casino: Player’s Collection PC yet.” MyAbandonware shows a single, bizarrely non-committal comment from a user “vonbikia” in 2026: “Very advocate for playing while in vacation.” This absence of discourse is the review’s most telling data point.

- Commercial Performance: No sales figures exist publicly. However, its presence on the abandonware site MyAbandonware, its multiple re-releases (as part of Casino VIP in 2007 and Casino Chaos! / Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection in 2011), and its availability for purchase used on eBay for under $10 years later point to a product that had enough shelf life and low production cost to be re-purposed and re-sold repeatedly. It met its commercial purpose as a low-risk SKU for ValuSoft.

Its legacy is one of ephemeral utility. It did not influence any major developers or spawn a successful series. Its “legacy” is as a data point in the history of:

1. The Budget Compilation: It exemplifies the “bag of games” model that thrived in pre-Steam, retail-dominated PC software sections.

2. The Casualization of Casino Games: It represents the stripping away of casino “narratives” (tension, bluffing, social interplay) to isolate pure, solitary mechanical play, a trend that would explode in the social/mobile casino game boom a decade later.

3. A Specific 3D Transition: It was part of the wave of titles using basic 3D animations to update 2D classics for the new millennium, a transitional phase in graphics.

4. Digital Preservation’s Edge: Its status as abandonware, preserved on the Internet Archive and MyAbandonware, makes it a candidate for historical study of early-2000s UI design, 3D asset creation for budget titles, and the packaging of gambling simulators for the home PC.

Conclusion: A Virtual Chip with No Value in the Museum, But Infinite Value as a Specimen

To assign a star rating or a traditional “verdict” to Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection is to fundamentally misunderstand its purpose and existence. It was never meant to be “good” in the sense of a compelling narrative experience or a mechanically deep simulation. It was meant to be adequate.

As a historical artifact, however, it is fascinatingly, comprehensively adequate. It is a perfect lens through which to view the machinery of early-2000s casual gaming: the ValuSoft business model, the Antidote Entertainment production pipeline, the technological midpoint between 2D sprite-casinos and fully immersive 3D worlds, and the complete divorce of gambling from story. It is a game with no soul, no ambition, and no impact—qualities that, in their totality, make it an exceptionally clear and pure example of a commercial product designed for a specific, narrow function.

Its place in video game history is not on a pedestal but in a vitrine labeled “Early 2000s Value-Priced PC Compilations.” It is a functional, forgettable piece of software that successfully (if quietly) fulfilled its commercial mission. To study it is to study the silent majority of game development—the titles that sold quietly in Walmart, were later bundled in discount packs, and now rot on the servers of abandonware sites. It is a ghost in the machine of the industry, a reminder that for every Half-Life 2 or World of Warcraft, there were hundreds of Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collections, ensuring the economic ecosystem stayed afloat. For that unglamorous, systemic role, it deserves not a recommendation, but a respectful, analytical nod. It is, ultimately, a perfectly rolled die in a long-forgotten game.