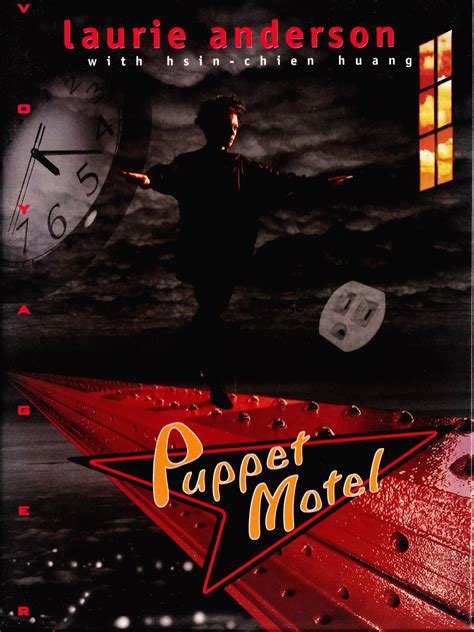

- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: The Voyager Company

- Developer: The Voyager Company

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Music, rhythm

- Setting: Hotel

Description

Laurie Anderson’s Puppet Motel is an interactive multimedia experience created by performance artist Laurie Anderson, set in a surreal, dreamlike motel called the ‘Hall of Time,’ where players navigate through 33 symbol-filled rooms filled with ethereal music, videos, monologues, and interactive art installations drawing from Anderson’s career. Beginning with a glowing electrical outlet that leads into a shadowy corridor, the game features bizarre elements like exotic musical instruments, floating telephones, maze-like chairs, and philosophical recitations, such as Plato’s Cave allegory, encouraging players to solve puzzles, respond via voice or text, and explore meditative themes of time, perception, and creativity while Anderson occasionally appears as a puppet-like guide.

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

wordyard.com : She has created a freestanding work of art — one that captures the soul of a blue machine.

Laurie Anderson’s Puppet Motel: Review

Introduction

Imagine stepping into a dimly lit hallway where time itself seems to stretch into infinity, walls lined with glowing icons that whisper promises of forgotten memories and technological reveries. This is the haunting allure of Laurie Anderson’s Puppet Motel, a 1995 CD-ROM that transcends the boundaries of traditional gaming to become a digital odyssey of art, introspection, and existential unease. As a pioneering work in the multimedia landscape of the mid-1990s, it captures the zeitgeist of an era when CD-ROMs promised to blur the lines between performance art, interactive fiction, and personal computing. Created by avant-garde icon Laurie Anderson in collaboration with designer Hsin-Chien Huang and published by The Voyager Company, Puppet Motel isn’t just a game—it’s a meditative portal into Anderson’s psyche, inviting players to navigate a surreal motel of the mind. My thesis: While its technological limitations and niche appeal may relegate it to obscurity today, Puppet Motel stands as a seminal art game that prefigures the introspective, non-linear experiences of modern interactive media, earning its place as a bold experiment in digital storytelling that prioritizes emotional resonance over escapist thrills.

Development History & Context

The mid-1990s marked a golden age for experimental multimedia on CD-ROM, a format that allowed creators to harness the power of optical discs for rich audio, video, and interactivity without the constraints of floppy disks or early hard drives. Laurie Anderson’s Puppet Motel emerged from this fertile ground, developed and published by The Voyager Company, a New York-based firm renowned for its innovative “Expanded Books” and cultural CD-ROM titles like Who Built America? and Morton Subotnick’s Making Music. Voyager, founded in 1984, specialized in bridging high art with emerging digital technologies, often collaborating with artists to produce non-commercial, intellectually rigorous works. Their output reflected a commitment to the liberal arts in the digital realm, but financial pressures loomed large; Puppet Motel, alongside other titles, achieved only middling sales, contributing to layoffs and Voyager’s eventual decline by the late 1990s.

At the helm was Laurie Anderson, a multidisciplinary performance artist and musician whose career had long intertwined technology with human emotion. By 1995, Anderson was riding the wave of her 1994 album Bright Red, from which the title track “Puppet Motel” is drawn—a song evoking isolation and artificiality that perfectly suited the project’s themes. Anderson’s vision stemmed from her live performances, such as the epic United States (1983) and her Nerve Bible tour, where she satirized technological alienation through manipulated voices, custom instruments, and multimedia projections. For Puppet Motel, she sought to translate this to the interactive screen, envisioning a “motel” as a metaphor for transient, shadowy existence in the information age. Collaborating with Hsin-Chien Huang, a Taiwanese designer whose prior work The Dream of Time had won acclaim in multimedia art competitions, Anderson aimed to create an environment that responded to user input while maintaining her signature poetic detachment.

Technological constraints shaped the project’s form profoundly. Released initially for Macintosh in 1995 (with a Windows port in 1998), Puppet Motel ran on early Mac OS versions like System 7, requiring a CD-ROM drive—a novelty at the time that limited accessibility. Development relied on tools like Macromedia Director for its Lingo scripting, enabling Huang’s intricate programming of hotspots, animations, and audio layers. The team, including producers like Elizabeth Scarborough and programmers like Tim Gardner, navigated hardware limitations: 640×480 resolution, 8-bit color palettes, and modest video compression meant visuals were stylized rather than photorealistic. Audio, however, was a priority, with special programming by Mark Coniglio and Paul Messick ensuring binaural soundscapes. Internet integration was forward-thinking; players could download updates from Anderson’s website, hinting at networked experiences before broadband ubiquity.

The gaming landscape of 1995 was dominated by adventure puzzles like Myst—a massive hit that sold millions with its point-and-click exploration—and first-person shooters like Doom. Yet Puppet Motel carved a niche in the “art game” subgenre, alongside titles like The Residents’ Freak Show. It rejected narrative linearity for zen-like wandering, reflecting the era’s optimism about multimedia democratizing art, even as commercial viability favored mass-market entertainment. This context underscores Puppet Motel‘s radicalism: a product of artistic ambition amid a budding industry still grappling with interactivity’s potential.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Laurie Anderson’s Puppet Motel eschews conventional plotting for a fragmented, non-linear tapestry of monologues, vignettes, and philosophical musings, embodying Anderson’s performance art roots. There is no overarching “story” in the traditional sense—no hero’s journey or climactic resolution—but rather a dreamlike procession through 33 surreal rooms accessed via “The Hall of Time,” a vanishing-perspective corridor symbolizing the inexorable flow of digital ephemera. The narrative unfolds as a series of encounters, guided sporadically by Anderson’s puppet alter-ego—a ventriloquist’s dummy voiced with a pitch-lowered modulator, representing fractured identity and the puppeteering hand of technology.

At its core, the “plot” begins with a howling electrical outlet in the darkness, a portal into the motel’s labyrinth. Players navigate rooms evoking Anderson’s life and obsessions: one gallery showcases her exotic instruments, like the “tape bow violin,” a bow strung with magnetic tape that plays pre-recorded sounds, blurring human creation and mechanical reproduction. Another features floating telephone receivers on rigid, tree-like cords, evoking missed connections in an age of emerging telecom; televisions flicker with static, stand-ins for the noise of information overload. Clocks tick relentlessly, announcing time in robotic voices, reinforcing themes of transience.

Characters are sparse and ethereal. Anderson appears in digitized video as both her poised self—delivering wry monologues—and the melancholic dummy, whose pleas like “Love me” or “Remember me” pierce the void. These figures serve as unreliable narrators, their dialogues poetic interrogations rather than exposition. In the chair maze room, Anderson emerges waving flashlights like an airport attendant, reciting Plato’s Cave allegory: prisoners chained in shadows, mistaking illusions for reality. This motif recurs, positioning the player as a digital cave-dweller, glimpsing truths through flickering screens. A palm-reading sequence turns interrogative, with Anderson posing endless questions (“Had enough?”) that probe the player’s psyche without resolution, mirroring the one-sidedness of human-machine interaction.

Underlying themes delve into profound existential territory. Technological Alienation dominates: Anderson critiques post-industrial isolation, weaving in motifs from her tours—airplane kaleidoscopes symbolize fragmented journeys, while Ouija floorboards blend superstition with computation, suggesting technology as modern mysticism. The motel’s “puppet” motif explores identity loss; mannequins float forlornly, echoing the dummy’s voice, implying users as marionettes in a vast digital web. Memory and Loss permeate, with Easter eggs triggering hidden videos (e.g., the dummy performing “Puppet Motel”) that evoke nostalgia for analog eras. The soundtrack’s debut track “Down in Soho” adds urban melancholy, while whispers of “You are out of memory. Save. Save now.” transform computer errors into metaphysical laments—warnings of forgotten data mirroring erased lives.

Subtler layers include gender and performance: Anderson’s modulated dummy voice subverts ventriloquism’s patriarchal tropes, reclaiming agency in a male-dominated tech world. Interactivity personalizes the narrative; recorded voices and typed responses feed into responses, creating illusory dialogue. Yet, the lack of closure—rooms loop without true “exits”—underscores themes of inescapable cycles, making Puppet Motel a philosophical mirror rather than a resolved tale. This depth elevates it beyond novelty, inviting repeated dives into its thematic abyss.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

In an era of rigid adventure games, Puppet Motel‘s mechanics prioritize meditative exploration over goal-oriented progression, classifying it as a zen-paced interactive artwork rather than a puzzle-box challenge. Core loops revolve around point-and-click navigation in first-person perspective: from the Hall of Time, players select icons to enter rooms, then interact via hotspots to uncover media. There’s no inventory, health, or win condition; instead, success lies in discovery, with the game encouraging aimless wandering that can span hours without exhaustion.

Exploration and Interaction: The interface is intuitive yet subversive. The mouse pointer shape-shifts—into an ice skate, eraser, or Ouija planchette—signaling contextual actions. Hotspots trigger videos, audio clips, or mini-activities; for instance, in the instrument room, clicking the tape bow violin plays manipulated sounds tied to Anderson’s compositions. Puzzles are “art-jokes”—non-frustrating riddles like connecting celestial dots to form constellations or leaving messages on a virtual answering machine. These foster curiosity, but some require trial-and-error, such as finding hidden Easter eggs (e.g., clicking shadows for dummy performances). Voice recording integrates deeply: players speak into the mic for palm readings or Ouija queries, with the game echoing responses in Anderson’s modulated tones, creating a haunting feedback loop. Typed inputs allow messaging the dummy, yielding poetic replies that adapt to keywords, though responses are pre-scripted for cohesion.

Systems and Innovation: Progression is non-linear; rooms interconnect thematically (e.g., clocks link to time-themed monologues), but no map exists, promoting immersion. Internet features (pioneering for 1995) download updates like new videos or concert info, extending play beyond the disc. Audio systems shine: binaural design demands headphones, with whispers panning left-to-right for intimate, disorienting poetry. Flaws emerge from era constraints—load times for videos stutter on period hardware, and the Windows port (1998) feels tacked-on with minor bugs. UI is minimalist: a dark screen with subtle cues avoids clutter, but empty rooms can feel alarmingly sparse, risking boredom for non-art enthusiasts. Character “progression” is absent; instead, the player evolves through emotional engagement, unearthing layers like reversed mouse controls in a right-to-left reading anecdote, which disorients to simulate cultural dislocation.

Overall, mechanics innovate by subverting expectations: puzzles resolve into revelations, not keys, making Puppet Motel a precursor to walking simulators like Dear Esther. Its meditative rhythm rewards patience, though modern players might crave more structure.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Puppet Motel is a metaphysical motel—a liminal space blending Anderson’s psyche with digital surrealism—crafted to evoke isolation amid abundance. Set in an abstract “Puppet Motel,” it draws from hotel tropes (transient anonymity) but warps them into a cosmic labyrinth: the Hall of Time serves as lobby, its icon-adorned walls a menu of subconscious doors. Rooms vary wildly—a maze of chairs shadowed like Plato’s cave, a gallery of floating instruments, black voids illuminated by movable light squares revealing phantoms. Atmosphere is desolate yet intimate, fostering unease; shadows run across floors, parcels drift purposelessly, evoking a haunted hard drive where data ghosts linger.

Visual direction, led by Huang, embraces 90s limitations as strengths: limited palettes (blues, blacks, ethereal glows) create a “blue machine” melancholy, avoiding saturation for suggestion. Animations are sparse—translucent airplanes kaleidoscope, TVs flicker static—but hotspots burst with detail, like the dummy’s eerie twitches. This restraint builds tension, contrasting bloated contemporaries like Myst‘s vistas.

Sound design is the masterpiece, comprising over an hour of Anderson’s compositions, monologues, and effects. Ethereal tracks from Bright Red underpin exploration, with binaural whispers (“Love me”) panning spatially for immersion. Clocks chime robotically, phones ring hollowly, and the outlet howls as entry. Audio post-production by Sean Anderson and team ensures clarity, turning small sounds—rustling shadows, modulated pleas—into poetic carriers. These elements synergize: visuals tease, sound envelops, crafting an experience of information-age sorrow. The result? A world that lingers, contributing to a holistic, introspective journey where emptiness amplifies meaning.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Puppet Motel garnered niche acclaim but modest commercial fortunes, emblematic of Voyager’s artisanal approach in a market chasing blockbusters. Critics praised its artistry: Tap-Repeatedly/Four Fat Chicks awarded 80% (4/5 stars) in 1998, calling it a “quirky little title” that’s “intriguing and enthralling,” lauding Anderson’s mesmerizing presence and free-roaming exploration as a “Playskool activity center for adults.” CNET’s 1996 verdict was an unscored “Buy It,” deeming it “so cool, words just don’t do it justice.” Digital Culture (via Wordyard) hailed it as a “freestanding work of art” transcending games, while The Obscuritory later described it as “dark, confusing, desolate, and beautiful.” Player scores averaged 3.7/5 on MobyGames (one rating), reflecting its polarizing zen appeal.

Commercially, it underperformed; non-mass-market pricing and Mac exclusivity limited reach, contributing to Voyager’s layoffs by 1997. Evolving reputation has grown cult status: as CD-ROMs faded, Puppet Motel became a historical artifact, inaccessible on modern hardware (requiring emulators or vintage Macs). YouTube excerpts preserve snippets, but no reissue exists, underscoring preservation challenges. Its influence ripples through art games—prefiguring The Beginner’s Guide‘s introspection, Proteus‘ ambient exploration, and even VR experiences like The Fisher’s Tale. Anderson’s dummy motif echoes in titles like Drunk Puppet, while its tech-critique anticipates Her Story or Device 6. In industry terms, it championed multimedia as art, influencing indie devs to blend music, narrative, and interaction, cementing Voyager’s legacy despite closure. Today, amid digital nostalgia, Puppet Motel reminds us of interactivity’s artistic potential.

Conclusion

Laurie Anderson’s Puppet Motel is a luminous enigma—a digital motel room where technology’s shadows dance with human longing, crafted with visionary precision amid 1990s constraints. From its fragmented narrative probing alienation and memory, to meditative mechanics that reward poetic discovery, Huang and Anderson’s collaboration weaves a tapestry of surreal beauty. Visually sparse yet sonically immersive, it builds a world that haunts long after the screen fades. Though commercial obscurity and accessibility woes dim its light, its critical reverence and subtle influence on art games affirm its historical significance. Verdict: An essential, if elusive, milestone in video game history, Puppet Motel earns a resounding recommendation for those seeking art that whispers truths in the machine’s ear—a 9/10 for its enduring, soul-stirring innovation.