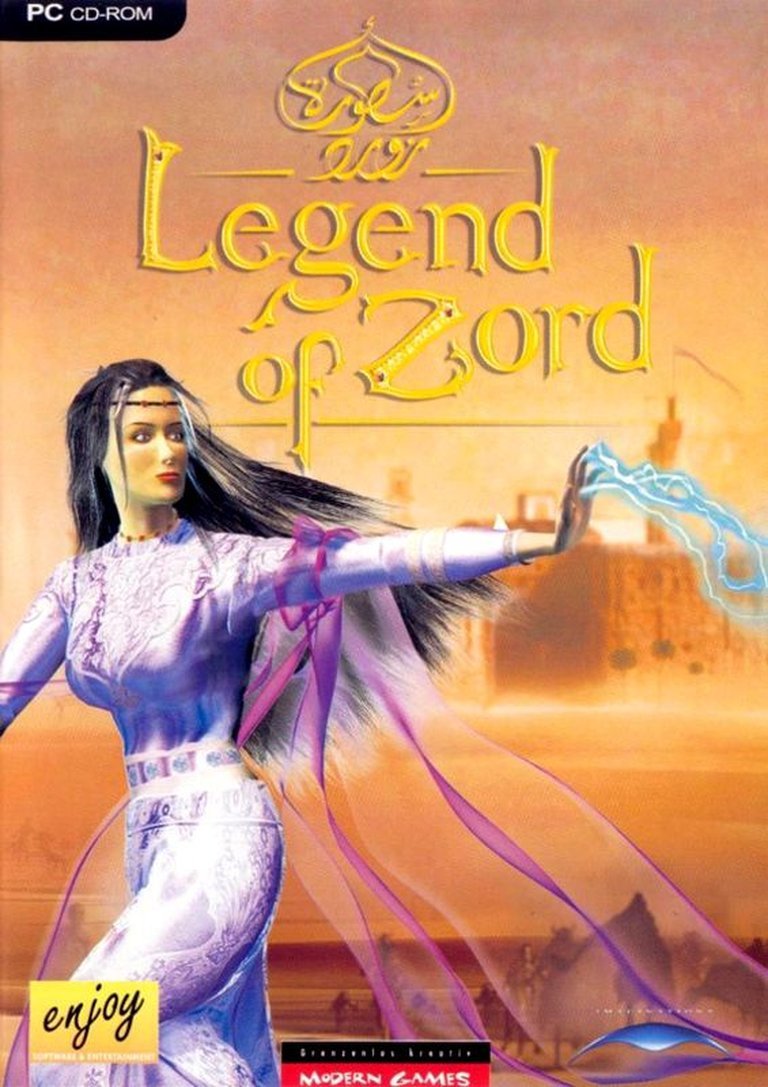

- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: BMS Modern Games Handelsagentur GmbH, enjoy Software & Entertainment GmbH, Imaginations FZ LLC, Media-Service 2000

- Developer: Imaginations FZ LLC

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Character transformation, Melee Combat, Spell casting, Third-person, Weapon selection

- Setting: Fantasy, Oriental

- Average Score: 38/100

Description

In the ancient land of Zord, ruled by the wise King Gilgamesh 5000 years ago, a jealous rival king from the bordering kingdom of Askhar invoked a demon to annihilate its prosperous inhabitants out of envy for its wealth. Prince Raymond, the sole survivor, embarks on a vengeful quest through diverse levels like oriental palaces and sewers in this 3rd-person action game, wielding six weapons, 18 spells, and the ability to transform into a lion or hawk to battle demonic hordes and undead foes.

Gameplay Videos

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Legend of Zord: A Flawed Oriental Epic in the Shadows of Gaming History

Introduction

Imagine a video game that dares to transport players to an ancient Arabian fantasy world, where princes battle demons amid opulent palaces and treacherous sewers, all developed in the heart of the Middle East during a time when Western studios dominated the industry. Released in 2003, Legend of Zord promised a revenge-fueled adventure steeped in cultural mythology, but it stumbled into obscurity due to technical woes and underdeveloped execution. As a game historian, I see it as a bold, if ultimately unsuccessful, artifact from an underrepresented corner of global game development—a Middle Eastern studio’s attempt to blend Eastern folklore with Western action-adventure tropes. This review argues that while Legend of Zord harbors intriguing ambitions in narrative and setting, its pervasive bugs, clunky mechanics, and dated visuals render it more a cautionary tale than a playable classic, deserving study for its cultural significance rather than replay value.

Development History & Context

Legend of Zord emerged from Imaginations FZ LLC, a small studio based in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, during the early 2000s—a period when the global gaming landscape was rapidly evolving but still heavily Euro-American centric. Founded amid the UAE’s burgeoning tech scene, Imaginations sought to infuse games with Arabic cultural elements, drawing from fables, myths, and traditional instruments to create an “oriental” experience. The game’s credits list 39 contributors, a modest team including designers like Piotr Kulik and Radosław Kurczewski (likely Polish expatriates), graphics artist Mustafa R. Alkhuzai, and programmers Anna and Roman Lichszteld. Concept design and animation were handled by a mix of international talent, with Mustafa R. Alkhuzai shaping the visual identity and Mindloop Studios composing the soundtrack featuring Arabic artists like Khalil Al Gadrzl and Shadi Bashir.

The vision, as gleaned from promotional materials and credits, was to craft a third-person action game that celebrated Arabian heritage—evoking tales like One Thousand and One Nights (reflected in its Russian title, 1001 noch’: Legenda o Zorde). Publishers like enjoy Software & Entertainment GmbH (Germany) and BMS Modern Games Handelsagentur GmbH distributed it primarily in Europe and the Middle East, targeting a niche audience with its USK 12 rating for moderate violence. Released on January 13, 2003, for Windows via CD-ROM, it arrived in an era dominated by polished 3D action titles like Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (2003) and Tomb Raider sequels, which set high bars for fluid animation and level design.

Technological constraints of the time played a significant role. Early 2000s PCs varied wildly in hardware, from basic Pentium III systems to high-end GeForce 4 setups, leading to compatibility issues that plagued the game. Imaginations operated on a shoestring budget, evident in the limited animation cycles and pixelated textures, reminiscent of pre-3D accelerators. The gaming landscape post-9/11 heightened sensitivity to Middle Eastern themes, potentially limiting marketing, while the indie-like production values couldn’t compete with Ubisoft’s cinematic flair. Patches were promised by publishers like enjoy-Software to address bugs, but documentation is scarce, suggesting the fixes never fully materialized. In context, Legend of Zord represents a rare early effort from a non-Western studio to enter the mainstream PC market, predating the UAE’s modern gaming boom (e.g., studios like Those Awesome Guys today), but it highlights the challenges of breaking into an industry biased toward established powerhouses.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Legend of Zord weaves a straightforward tale of vengeance rooted in ancient mythology, set 5,000 years ago in the prosperous land of Zord—a fictional Arabian kingdom inspired by Mesopotamian epics like the Epic of Gilgamesh. The wise King Gilgamesh (a nod to the historical Sumerian figure) rules alongside his son, Prince Raymond (sometimes spelled Raymon in promo materials), fostering a thriving trade hub between East and West. Envy festers in the neighboring realm of Askhar, where its unnamed king, driven by greed, summons a demonic wizard—the “Demon King”—to unleash hordes of undead and monsters upon Zord. The assault culminates in Gilgamesh’s betrayal and death, leaving the kingdom in ruins. Prince Raymond, the sole survivor, embarks on a quest to avenge his family, battling through 16 levels to restore order and confront the invaders.

The plot unfolds linearly across these stages, from opulent oriental palaces to labyrinthine sewers and besieged cities, with Raymond as the primary protagonist. Mid-game, the narrative introduces character-switching mechanics, allowing control of allies or transformed forms (more on this in gameplay), implying a broader resistance against the demonic forces. Dialogue is sparse—limited to cutscenes and environmental storytelling—focusing on Raymond’s internal monologue of loss and resolve. Themes of jealousy as a corrosive force echo biblical and Quranic parables, while the demon invocation draws from Islamic jinn lore and pre-Islamic Arabian folklore, positioning Zord as a beacon of wisdom corrupted by ambition. The story’s ambition to reflect “the world of fables and myths of the Orient” (per Amazon’s product description) is evident in elements like communicating with rats, spiders, and giant monsters, evoking shape-shifting djinn or animal allies in tales like Aladdin.

However, the execution falters deeply. Characters lack depth: Raymond is a archetypal hero with “unique skills in sword fighting,” but no backstory beyond his royal lineage; the Askhar king is a faceless villain, and the Demon King a generic antagonist. Dialogue, when present, feels translated awkwardly (the game supports English and Arabic, per some releases), with stilted lines that fail to evoke emotional investment. Underlying themes of cultural pride and redemption are undermined by repetitive enemy encounters—zombies and “Schreckensgestalten” (horror figures)—that reduce the epic to a slaughterfest. Critics like PC Games noted the “old-fashioned” story, comparing it unfavorably to Prince of Persia, where acrobatic puzzles intertwined with narrative. Ultimately, the themes offer a refreshing non-Western lens on revenge fantasy, but the thin plot and absent character arcs make it feel like an outline rather than a deep dive, more suited to a short story than a full game.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Legend of Zord adopts a familiar third-person action loop akin to early Tomb Raider or Diablo hybrids: explore linear levels, engage enemies in real-time combat, and progress via collected power-ups. Players control Prince Raymond (and later variants) using keyboard for WASD-style movement and mouse for camera, targeting, and attacking—click to swing weapons or cast spells. The core hook is a arsenal of six weapons (e.g., swords, implied from the “oriental” aesthetic) and 18 spells, allowing tactical variety: fireballs for ranged assaults, buffs for melee dominance, or summons for crowd control. Progression involves defeating “everything [you] see,” with loot granting upgrades; later, transformations into a lion (for brute strength) or hawk (for aerial scouting and strikes) add mobility, while character-switching enables puzzle-solving or alternate paths.

The 16 levels form the backbone, progressing from tropical oases and endless deserts to urban sieges, blending hack-and-slash with light platforming. Innovative systems include animal communication for hints or aid, and a “Matrix-like” jump mechanic for traversing gaps—though critics derided its imbalance, making monster hordes trivial while simple obstacles frustrating. UI is basic: a hotbar for weapons/spells, health/mana bars, and a minimap, but it’s cluttered and unresponsive, with poor collision detection causing “nerve-wracking” failures (per PC Games).

Flaws abound, as German reviews unanimously highlight. Controls are “üble” (vile), with imprecise mouse aiming leading to missed swings; animations are “lächerlich” (ridiculous), limited to few phases that make combat feel wooden, like “Augsburger Puppenkiste” puppets (GameStar). Enemy AI is “nicht vorhanden” (non-existent), with foes pathfinding poorly or clipping through walls. Bugs are rampant—crashes at fixed points, missing textures, and unplayable sections—rendering it “unspielbar” (unplayable) on many setups (Looki, Game Captain). Progression feels unbalanced: easy enemy slaying contrasted with finicky jumps over “two-meter-wide chasms.” No multiplayer or robust RPG elements exist; it’s single-player only, with no save system details, exacerbating frustration. In sum, the mechanics innovate modestly with transformations but collapse under technical ineptitude, evoking a beta more than a finished product.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Zord aims for an immersive Arabian fantasy, with levels evoking One Thousand and One Nights: palatial interiors with arched doorways, sun-baked deserts, and shadowy sewers teeming with undead. Atmosphere builds through environmental storytelling—ruined bazaars hint at lost prosperity, demonic altars underscore invasion themes—fostering a sense of desecrated heritage. Transformations enhance exploration: a hawk’s flight reveals hidden oases, while lion form smashes barriers, tying mechanics to lore.

Visually, however, it’s a letdown. Graphics “ruckelt erbärmlich” (stutter miserably), with pixelated textures and “klobigen Objekten” (clunky objects) reminiscent of late-90s 3D (PC Action). Levels suffer from “öde” (dreary) design: houses as flat 2D textures without interiors, empty corridors, and repetitive enemy spawns (PC Games). Animations are sparse—Raymond’s sword swings loop awkwardly, enemies jerk like marionettes—failing to capture the fluidity of contemporaries like Onimusha. The art direction, led by Mustafa R. Alkhuzai, shows promise in concept sketches (oriental motifs, vibrant palettes), but low-poly models and DirectX-era limitations result in a “triste” (dreary) aesthetic.

Sound design fares better, a rare bright spot. Mindloop Studios’ soundtrack blends traditional Arabic instruments (oud, qanun) with modern orchestration, featuring artists like Layal Watfeh for an evocative, cultural authenticity. Ambient effects—echoing palace winds, demonic growls—build tension, though combat audio is tinny and repetitive. Voice acting is minimal, likely localized poorly for German markets, with no English dubs noted. Overall, these elements aspire to a rich oriental atmosphere but are sabotaged by technical shortcuts, contributing to immersion only in fleeting moments, like a haunting desert melody amid glitchy sands.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Legend of Zord bombed critically, earning a dismal 17% average from six German outlets—Looki (24%), PC Action (23%), Gameswelt (20%), Game Captain (15%), GameStar (12%), and PC Games (9%)—with unanimous pans for bugs, graphics, and controls. Reviewers like Gameswelt suggested waiting for patches (which enjoy-Software acknowledged but likely underdelivered), while PC Games quipped it’s a “Must-Have for… actually no one.” Commercially, it faded into obscurity; no sales figures exist, but its low MobyScore (4.3/10 from four players) and single collector on MobyGames indicate minimal uptake. Player ratings average 2.5/5, with complaints mirroring critics: unplayable crashes and masochistic tedium.

Its reputation hasn’t improved; as an “orphan” Wikipedia article with few links, it’s preserved on abandonware sites like My Abandonware (rated 3/5 by five votes) but lacks modern re-releases or remasters. Influence is negligible—no direct successors cite it, though tangential credits link to games like Serious Sam. It subtly highlights early Middle Eastern dev challenges, predating successes like The First Arabian Nights (unrelated) or UAE’s esports scene. In industry terms, it underscores 2003’s pitfalls for indie 3D action games, echoing flops like Die by the Sword but without cult appeal. Today, it’s a historical footnote: downloadable for nostalgia, but emblematic of how ambition without polish dooms titles to the bargain bin.

Conclusion

Legend of Zord stands as a poignant relic of 2003’s gaming frontier—an ambitious fusion of Arabian mythology and third-person action that falters under waves of bugs, archaic mechanics, and visual shortcomings. Its narrative of royal vengeance and cultural themes offer a unique lens, bolstered by evocative music, but repetitive combat, unrefined systems, and technical instability make it unendurable for modern players. As a historian, I commend Imaginations FZ LLC’s vision in bringing Middle Eastern storytelling to PCs during a Western-dominated era, but as a journalist, I must deem it a curiosity, not a gem. Definitive verdict: Skip for gameplay, but seek out for academic dives into global game dev history—it’s a flawed legend worth remembering, if not revisiting. Rating: 2.5/10.